The Case

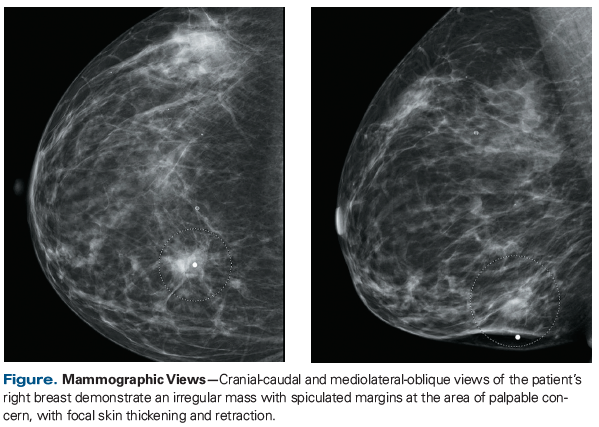

A 35-year-old woman noticed a mass in her right breast and underwent a diagnostic workup, including a mammogram that revealed a 2.4-cm mass (Figure) and ultrasound that showed two adjacent masses measuring 1.6 and 0.9 cm, as well as enlarged axillary lymph nodes. Biopsies were performed on two breast lesions and an axillary lymph node; all revealed intermediate-grade invasive ductal carcinoma that was positive for estrogen receptor (ER; 3+ in 100% of tumor cell nuclei) and progesterone receptor (PR; 3+ in 10% of tumor cell nuclei), and equivocal for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) by immunohistochemistry (IHC; 2+), but negative for HER2 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), with a HER2/CEP17 ratio of 1.3. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and whole-body bone scintigraphy showed no evidence of distant metastatic disease, and the patient’s disease was classified clinically as stage IIA(T1cN1M0). She had a family history of breast cancer in several second-degree relatives; germline genetic testing was performed but results were notable only for a variant of the APC gene of undetermined significance.

The patient was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (4 cycles, dose-dense, every 14 days) followed by weekly paclitaxel for 12 weeks, which was well tolerated. Following chemotherapy, the patient chose to undergo bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy, right sentinel lymph node biopsy, and delayed reconstruction. Two of four sentinel lymph nodes were positive, so she underwent a subsequent axillary dissection. Her final pathology revealed residual multifocal grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma in the right breast, with the largest focus measuring 8 mm; two of six lymph nodes were positive. Repeat receptor testing on the invasive cancer showed that the tumor was positive for ER (3+ in 100% of tumor cell nuclei) and PR (3+ in 10% of tumor cell nuclei); was equivocal for HER2 by IHC (2+) but was HER2-positive by FISH, with a HER2/CEP17 ratio of 2.35. The patient completed post-mastectomy radiation, 50 Gy in 25 fractions to the chest wall and undissected regional lymph nodes. She returned to the breast oncology clinic to discuss further adjuvant therapy.

Which of the following represents the most reasonable next step in management for this patient?

A. Tamoxifen for 10 years

B. Docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab × 6 cycles, trastuzumab to complete 1 year, and tamoxifen for 10 years

C. Trastuzumab and pertuzumab for 1 year, long-term aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy along with ovarian suppression

D. Trastuzumab for 1 year, followed by neratinib for 1 year; long-term AI therapy along with ovarian suppression

E. Trastuzumab and pertuzumab for 1 year, followed by neratinib for 1 year; tamoxifen for 5 years

Correct Answer: D

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second-most lethal cancer in women in the United States. Upon pathologic diagnosis, tissue samples are tested for overexpression of HER2, in addition to hormone receptor expression, to guide systemic therapy. HER2 is overexpressed in 15% to 20% of invasive breast cancers, and it was historically associated with a poor prognosis.[1] Adding trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting HER2, to adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer decreases risk of recurrence by approximately 50%, with an overall survival benefit observed in multiple large phase III randomized trials.[2-5] While the standard of care for these patients is to administer trastuzumab concurrent with chemotherapy, the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 trial did show a significant disease-free survival (DFS) benefit for adding sequential trastuzumab following paclitaxel. With a 6-year median follow-up, the 5-year DFS rate was 71.8% in arm A (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel [AC-T] alone) vs 80.1% in arm B (AC-T followed by sequential trastuzumab for 52 weeks).[6] These results support administration of 52 weeks of trastuzumab concurrent with adjuvant hormonal therapy in this patient, despite the fact that she already completed her planned chemotherapy.

Although use of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer has been part of the standard of care for many years, the recent approvals of pertuzumab and neratinib by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) add to the complexity of decision-making for this patient. Pertuzumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the HER2 dimerization domain, preventing HER2 dimerization with other HER family receptors. The addition of 1 year of adjuvant pertuzumab to standard adjuvant chemotherapy and 1 year of trastuzumab was evaluated in the recently published APHINITY trial. In that trial, pertuzumab was initiated concurrent with the first cycle of taxane chemotherapy and trastuzumab, with continuation to complete 1 year of therapy. This trial showed that in patients with node-positive or high-risk, node-negative HER2-positive operable breast cancer, adding pertuzumab reduced incidence of invasive breast cancer recurrence from 8.7% to 7.1%.[7] The invasive disease–free survival (iDFS) rate at 3 years was 94.1% in the pertuzumab group and 93.2% in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66–1.00; P = .045). In a preplanned subset analysis in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease, the 3-year iDFS rate was essentially the same in the two groups: 94.8% in those who received pertuzumab and 94.4% in the placebo group. Patients in the APHINITY trial did not receive adjuvant neratinib.

Neratinib is an irreversible small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER1, HER2, and HER4 that was evaluated as extended adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk, node-negative or node-positive, HER2-positive breast cancer in the phase III randomized controlled ExteNET trial.[8] Patients were randomly assigned to receive neratinib or placebo for 1 year after standard locoregional treatment, trastuzumab, and chemotherapy. Eligibility criteria for this trial were amended to limit enrollment to patients with node-positive disease. In addition, the interval between completion of trastuzumab and enrollment was shortened from 2 years to 1 year. In this trial, neratinib improved iDFS compared with placebo at 5 years (90.2% vs 87.7%; HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57–0.92; P = 0.0083). This effect was more pronounced in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease (91.2% vs 86.8%; HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43–0.83), and there was no difference in iDFS with neratinib administration compared with placebo in hormone receptor–negative disease. The differing benefit from adding neratinib in hormone receptor–positive and hormone receptor–negative disease is curious and has not been observed in trials of other anti-HER2 regimens in the adjuvant setting. The benefit of neratinib in hormone receptor–positive, HER2-positive breast cancer is hypothesized to be caused by sensitization of estrogen receptor signaling to hormonal agents or by pathway crosstalk.[8] One of the criticisms of the ExteNET trial, however, is that it did not include patients treated with pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. This is significant, because it raises the question of whether triple-HER2 antagonism might amplify the effect size produced by either trastuzumab and pertuzumab or trastuzumab and neratinib.

This patient ultimately was found to have node-, hormone receptor–, and HER2-positive disease. Thus, the addition of both HER2-targeted therapy and hormonal therapy is indicated. Neglecting to address emergence of HER2 positivity in this woman would be inappropriate, making Answer A incorrect. Also, there are no data to suggest further chemotherapy in this setting: thus, Answer B also is incorrect.

The addition of pertuzumab or neratinib-or both-to trastuzumab therapy should be based on an individual patient’s risk profile. This woman did not receive pertuzumab or trastuzumab as part of her neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen, given her initial IHC and FISH results. Although we did consider adding pertuzumab to planned adjuvant trastuzumab (Answer C), we did not strongly recommend this treatment option to the patient based on lack of data for sequential administration of pertuzumab after completion of chemotherapy, and the modest benefit in improvement in iDFS observed in the APHINITY trial. Our decision was also influenced by the diminished effect of pertuzumab observed in the hormone receptor–positive subgroup of that trial, and our interest in considering adjuvant neratinib following completion of trastuzumab. Answer C is not the most reasonable next step here.

There currently are no clinical trial data to define the benefit of administering both pertuzumab and neratinib in this patient, and ovarian suppression plus an AI or tamoxifen, or tamoxifen for 10 years, is favored over 5 years of tamoxifen in young patients with high-risk disease; thus, Answer E is incorrect. Because of this patient’s hormone receptor positivity, neratinib would be expected to further reduce her risk of recurrence in combination with long-term AI therapy along with ovarian suppression, given the results of the ExteNET trial.

That said, neratinib’s side effect profile must also be considered whenever adding this drug to adjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer is an option. Neratinib’s major dose-limiting toxicity is diarrhea. In the ExteNET trial, grade 3 diarrhea occurred in approximately 40% of those who received the drug (vs 2% in the placebo group) and led to dose reductions in 26% of patients. Diarrhea occurred more frequently and severely at initiation of therapy and decreased as therapy continued. The degree of toxicity associated with neratinib in the ExteNET trial is concerning, as it could undermine patient compliance and interfere with quality of life.[9] Of note, however, antidiarrheal prophylaxis was not originally incorporated into the ExteNET trial and can be effective in managing this life-altering side effect.[10] Antidiarrheal prophylaxis with loperamide is recommended in the FDA-approved package insert for neratinib. Adding colestipol, a bile acid sequestrant, to loperamide prophylaxis may further reduce incidence of grade 3 diarrhea and increase the percentage of patients who experience no diarrhea.[11] Given the availability of effective prophylaxis for adverse effects of neratinib, Answer D is the most reasonable next step in management for this patient.

KEY POINTS

- The prognosis of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer has been markedly improved with the addition of adjuvant HER2-targeted therapies, most notably trastuzumab.

- Neratinib, an irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER1, HER2, and HER4, is approved for extended adjuvant treatment in patients with early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer following 1 year of trastuzumab, based on the results of the ExteNET trial. In that trial, benefit was limited to patients with hormone receptor–positive disease in subset analysis.

- Neratinib should be administered with antidiarrheal prophylaxis using loperamide, and colestipol can be considered as an adjunct.

- Tumor markers can change after neoadjuvant therapy in a small but potentially meaningful number of cases, underscoring the need to tailor adjuvant therapy to an individual patient.

This case effectively showcases the potential for emergence of HER2-positive disease following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Several studies have investigated changes in tumor markers following breast cancer treatment, including following neoadjuvant therapy. Prolonged in vitro exposure to tamoxifen in hormone receptor–positive breast cancer cell lines leads to an increase in HER2 mRNA and protein expression; this was confirmed in serum samples obtained from patients with metastatic hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer who received first-line systemic hormonal therapy.[12] In this study, approximately 25% of patients had acquired serum HER2 positivity at the time of disease progression, as determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay specific for the extracellular domain of HER2. These patients had shorter survival than those who experienced disease progression without serum HER2 positivity.[12] Another large retrospective study conducted in Japan evaluated hormone receptor status and HER2 expression before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in >20,000 patients, using Japanese breast cancer registry data. This study found that among those who initially presented with HER2-positive disease, 21.4% were HER2-negative after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab. Conversely, 3.4% of patients with HER2-negative disease converted to HER2-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.[13]

Both the prevalence of changing tumor markers following neoadjuvant therapy and the evolution of effective targeted therapies are testaments to the fact that adjuvant therapy must be tailored to an individual patient.

Outcome of This Case

Following radiation therapy, the patient completed 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with hormonal therapy. She was initially treated with exemestane in combination with ovarian suppression, as supported by the TEXT and SOFT trials, and she subsequently underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, given that her childbearing was complete and per her preference.[14] Exemestane was replaced by anastrozole due to adverse effects of the former, and the patient initiated extended adjuvant therapy with neratinib after completing 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab. She is currently receiving maintenance therapy with neratinib and anastrozole and has had no clinical evidence of recurrence.

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no significant financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

E. David Crawford, MD, serves as Series Editor for Clinical Quandaries. Dr. Crawford is Professor of Surgery, Urology, and Radiation Oncology, and Head of the Section of Urologic Oncology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine; Chairman of the Prostate Conditions Education Council; and a member of ONCOLOGY's Editorial Board.

If you have a case that you feel has particular educational value, illustrating important points in diagnosis or treatment, you may send the concept to Dr. Crawford at david.crawford@ucdenver.edu for consideration for a future installment of Clinical Quandaries.

References:

1. Moja L, Tagliabue L, Balduzzi S, et al. Trastuzumab containing regimens for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD006243.

2. Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673-84.

3. Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659-72.

4. Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1273-83.

5. Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, et al. 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1021-28.

6. Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al. Sequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4491-7.

7. Minckwitz G, Proctor M, De Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:702.

8. Martin M, Holmes FA, Ejlertsen B, et al. Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): 5-year analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1688-700.

9. Vogl S. (2017, December 25). Neratinib is approved: should we reject it anyway? ASCO Post. 2017 Dec 25. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/december-25-2017/neratinib-is-approved-should-we-reject-it-anyway/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

10. Ustaris F, Saura C, Di Palma J, et al. Effective management and prevention of neratinib-induced diarrhea. Am J Hem Oncol. 2015;11:13-22.

11. Hurvitz S, Chan A, Iannotti N, et al. Effects of adding budesonide or colestipol to loperamide prophylaxis on neratinib-associated diarrhea in patients with HER2+ early-stage breast cancer: the CONTROL trial. Proceedings of the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 2017 Dec 5-7; San Antonio, TX; abstr P3-14-01.

12. Lipton A, Leitzel K, Ali SM, et al. Serum HER-2/neu conversion to positive at the time of disease progression in patients with breast carcinoma on hormone therapy. Cancer. 2005;104:257-63.

13. Niikura N, Tomotaki A, Miyata H, et al. Changes in tumor expression of HER2 and hormone receptors status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 21 755 patients from the Japanese breast cancer registry. Ann Oncol. 2015;27:480-7.

14. Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GI, et al. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:436-46.