Amonafide Regimen Not Superior to Standard Care in Secondary AML

Induction treatment for acute myeloid leukemia with amonafide L-malate/cytarabine failed to improve the rate of complete response over daunorubicin/cytarabine.

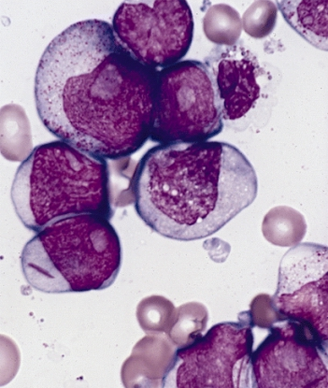

Bone marrow smear from a patient with acute myeloid leukemia

Induction treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with amonafide L-malate plus cytarabine failed to improve the rate of complete response compared with treatment with daunorubicin plus cytarabine, according to the results of a study designed to test treatment with amonafide L-malate, a DNA intercalator and non–ATP-dependent topoisomerase II inhibitor that evades drug resistance mechanisms.

“On the basis of previous phase I and II clinical trial data and a mechanism of action including evasion of drug efflux, the induction regimen of [amonafide/cytarabine] held the promise of being superior to standard [daunorubicin/cytarabine] in patients with difficult-to-treat secondary AML,” wrote study researcher Richard M. Stone, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. “Our study demonstrated that the doses of amonafide used in the experimental arm plus cytarabine did not produce a higher complete response rate than the use of standard therapy with [daunorubicin/cytarabine]. Moreover, the amonafide-containing regimen was more toxic than standard induction, making it less likely that inadequate doses of amonafide were used in this study.”

The phase III study included 433 patients with previously untreated secondary AML. Patients were randomly assigned to cytarabine 200 mg/m2 once per day on days 1 to 7, combined with amonafide 600 mg/m2 over 4 hours on days 1 to 3 or daunorubicin 45 mg/m2 over 30 minutes once a day on days 1 to 3.

Rates of response were similar between the treatment arms. Forty-six percent of patients in the amonafide arm achieved complete response compared with 45% in the daunorubicin arm. The researchers also examined whether response difference occurred based on the subset of disease. They found that antecedent myelodysplastic syndrome was associated with a complete response rate of 40% compared with 50% in patients with prior leukemogenic exposure (P = .04); however, responses did not vary by treatment.

There were also no significant differences in 30-day (19% for amonafide vs 13% for daunorubicin) or 60-day mortality (28% vs 21%) between the two treatment arms. The researchers did find though that younger patients on amonafide had significantly longer survival compared with older patients (P = .001). Specifically, looking at only those patients aged younger than 56 years, the median overall survival was 16.1 months for the amonafide arm compared with 7.1 months for the daunorubicin arm (P = .03). Examining the rates of complete remission in these patients under 56, the authors found that 64% of patients receiving amonafide/cytarabine achieved complete remission compared with 40% for those receiving daunorubicin/cytarabine (P = .016).

“This clinical trial provides the medical community with the largest prospectively collected data set on induction therapy in secondary AML to our knowledge,” the researchers wrote. “Although amonafide does not seem to provide benefit over standard induction therapy with daunorubicin, analyses of the data from this clinical trial may provide critical background information for tests of subsequent drugs that may have promise in this important disease subgroup, such as the liposomal-encapsulated daunorubicin/cytarabine CPX-351, the nuclear export inhibitor KPT-330, or the BCL-2 antagonist ABT-199.”