Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation and Potential Strategies for Enrollment of Hispanic/Latinx Patients With Cancer

In a conversation during Hispanic Heritage Month, Ruben Mesa, MD, highlights factors that may contribute to disparities in clinical trial enrollment of Hispanic and Latinx patients with cancer and strategies that may encourage study participation.

Data have demonstrated that Hispanic patients with cancer are often diagnosed at later stages of the disease and have worse quality of life post diagnosis compared with non-Hispanic White patients.1 Numerous factors are thought to play into these disparities, including lack of health insurance and limited financial resources, in turn limiting access to standard treatment options and clinical trials. Cultural, psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors are also thought to play a role in these disparities.

However, diversity within the cancer space and in clinical cancer research has become a recent topic of interest in the United States and could stand to benefit not only the Hispanic and Latinx population, but other populations as well, according to Ruben Mesa, MD.

“We’re just learning the richness of diversity and the importance that it can have, both for us to be able to provide the very best care that we can for patients and for us to better understand cancer,” Mesa said. “The things that we learn can [likely] benefit all of us regardless of our backgrounds.”

During Hispanic Heritage Month, Mesa, executive director of Mays Cancer Center, home to The University of Texas San Antonio MD Anderson, sat down with CancerNetwork® to discuss disparities in outcomes facing Hispanic and Latinx patients, how a lack of enrollment on clinical trials can affect real-world patient outcomes, and how barriers to enrollment might be dismantled.

Be sure to read part 1 of our Hispanic Heritage Month series in which Mesa details disparities for Hispanic and Latinx patients with cancer.

Why Is Clinical Trial Participation a Challenge?

Despite Hispanic and Latinx individuals having lower incidence of certain cancer types vs White patients, the former are more likely to be uninsured or under insured, have lower income, and have more limited access to care.2,3 Such socioeconomic factors can lead to diagnosis at a more advance stages, lower 5-year overall survival, and increased rates of infection-based cancers. Participation in clinical trials has yielded improvement in survival for Hispanic and Latinx patients; however, notable racial, ethnic, and age-based disparities persist.

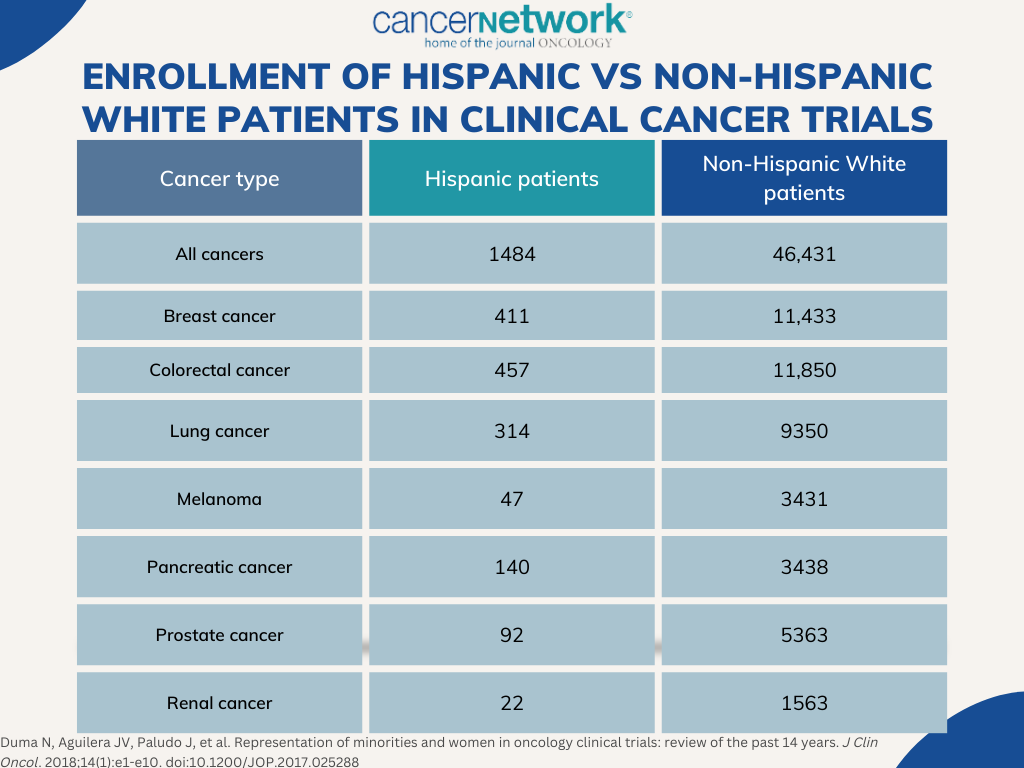

Although participation in clinical research could help to further improve outcomes in this population, Hispanic/Latinx patients comprise 2.3% to 3.9% of all therapeutic trial participants, with rates only decreasing over time.4 Underrepresentation is also observed in disease types for which the population is at higher risk, including liver, gastric, and cervical cancer. Several factors contribute towards racial/ethnic inequity in clinical research, starting with the study’s design. Twenty percent to 31% of clinical trials report race and/or ethnicity data. Despite legislation passed in 2017 requiring the reporting of racial and ethnic demographic data, it is not feasible to accurately measure and keep track of which studies are adhering to the new requirements (TABLE).

FIGURE. Enrollment of Hispanic Vs Non-Hispanic White Patients in clinical Cancer Trials

Several other factors have been cited as contributing factors towards disparities in clinical trial enrollment of Hispanic and Latinx patients with cancer, including lack of awareness, fear of adverse effects, suboptimal insurance status, poor socioeconomic status, transportation challenges, lack of access to academic or specialized treatment centers, language barriers, and a lack of trust in the medical community. For example, difficulties with English literacy could make comprehending complex protocol designs challenging.

In a 2013 survey conducted in a population of United States Latinx patients with cancer (n = 944), only 48% of patients reported knowing what a clinical trial was and 65% expressed a willingness to participate in clinical research.5 Factors such as being able to use the Internet to access health information (odds ratio [OR], 2.33; 95% CI, 1.63-3.34; P = .001), trust in health information (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.12-1.58; P = .001), and higher education were independently associated with odds of clinical trial awareness; however, receiving information from a provider did not have the same effect on knowledge. Moreover, contacting a cancer information service (OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.01-6.14; P = .05) and psychosocial factors such as greater worry, higher self-efficacy, and trust in information were independently associated with an intent to participate in clinical cancer research.

The investigators concluded that sources such as the Internet and call centers could be an effective way to communicate information about clinical trials. Although providers were a common source of information, they were not associated with knowledge of clinical trials, potentially presenting a blind spot in encouraging clinical trial enrollment.

Inequities in Clinical Research and Real-World Outcomes

As the data gleaned from clinical cancer research lead to better understanding of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer across various disease types, it becomes imperative that clinical trial populations reflect real-life counterparts receiving treatment.6 In particular, it is believed that lack of inclusion and representation in clinical research results in an overgeneralization of data based on outcomes observed in non-Latino White populations.

“Our goal with clinical trials is for them to really reflect our population,” Mesa explained. “The need for [better diversity is] 2-fold. First, it’s about social justice, meaning clinical trials are a critical part of how we treat cancer, particularly cancers that have failed our current therapies. It’s a necessary part of the treatment arc. If clinical trials aren’t enrolling individuals who are diverse, patients are being denied that critical care. The second is that it is a critical part of assessing whether a therapy is safe and effective. There can be important differences based on race, ethnicity, other genetic information, and practicality of ease of administration. That is very important for us to understand as the therapy goes from the research setting to actual use.”

Equal trial participation is of particular importance among underrepresented populations as it can result in fewer opportunities to identify effects relevant to specific groups and care. This could result in decreased opportunities to provide accessible and lifesaving treatment. Moreover, experts have cited an underrepresentation of Latinx and other populations in cancer research for enfeebling efforts to understand potential difference in treatment efficacy and tolerability in diverse populations.

Encouraging Trial Participation in Hispanic/Latinx Populations

A litany of strategies are currently under investigation to help encourage clinical trial participation of Hispanic and Latinx patients with cancer.6 For example, an analysis of 297 studies conducted at the Mays Cancer Center identified several factors—such as type of sponsor, trial author, and intervention type—as variables significantly associated with clinical trial accrual. Moreover, observational, interventional, and industry-sponsored trials, as well as trials penned by local primary investigators, were more likely to meet accrual goals. Based on this research, key leaders from the University of Colorado Health Colorado Springs and UT Health San Antonio are developing a predictive model for trial accrual.

Other strategies include involving nurses, nurse navigators, and clinical trial coordinators who have a keen understanding of clinical research. For example, the Massey Cancer Center of Virginia Commonwealth University employed a strategy that tapped into the expertise of resource specialists and clinical social workers to help patients identify resources such as transportation grants, childcare, or legal assistance. This reportedly helped free clinical research nurses to better direct their attention to patient care and treatment. A dedicated insurance authorization coordinator was also incorporated to better inform patients about their insurance policies with a focus on coverage and financial obligations.

“[Achieving equity] includes many parts. It includes trying to work alone or frequently with partners as it relates to prevention and screening. That typically has to be decentralized and accessible,” Mesa said. He cited simple solutions, such as having information in multiple languages and breaking down barriers built by misinformation surrounding life-saving therapies like HPV vaccines. “It clearly also includes trying to come up with creative solutions for barriers for transportation and extended hours. Many individuals in this who are minorities sometimes have employer-type barriers to care, meaning they’re paid hourly. They simply will delay care or have challenges with care because they can’t get off from work,” he concluded.

References

- Yanez B, McGinty HL, Buitrago D, et al. Cancer outcomes in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: an integrative review and conceptual model of determinants of health. J Lat Psychol. 2016;4(2):114-129. doi:10.1037/lat0000055

- Espinoza-Gutarra MR, Duma N, Aristizabal P, et al. The problem of Hispanic/Latinx under-representation in cancer clinical trials. JCO Oncol Prac. 2022;18(5):380-384. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00214

- Han X, Jemal A, Zheng Z, et al. Changes in noninsurance and care unaffordability among cancer survivors following the Affordable Care Act. J Nat Can Inst. 2020;112(7):688-697. doi:10.1093/jnci/djz218

- Wallington SF, Luta G, Noone AM, et al. Assessing the awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials among immigrant Latinos. J Comm Health. 2012;37(2):335-343. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9450-y

- Ramirez AG, Chalela P. Equitable representation of Latinos in clinical research is needed to achieve health equity in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2022;18(5):e797-e804. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00127

- Mesa RA, Ramirez AG. Overcoming barriers for Latinos on cancer clinical trials. In: Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos. Springer Nature; 2019:125-131.

How Supportive Care Methods Can Improve Oncology Outcomes

Experts discussed supportive care and why it should be integrated into standard oncology care.