Breast Cancer Screening in Older Women

Physicians can help older women make informed mammography decisions by taking into account life expectancy and the harms and benefits of breast cancer screening.

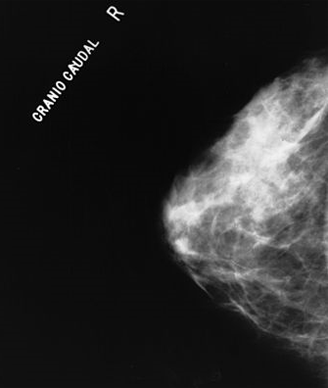

Normal mammogram

Physicians can help women 75 or older make informed decisions about continuing screening mammography by providing individualized counseling that takes into account their life expectancy along with the potential harms and benefits of screening, a recent review concluded.

“Women should be asked how they feel about the potential benefits and harms of screening and factor in their goals and values to make an individualized screening decision,” researchers wrote last month in JAMA. “Different individuals with the same trade-offs might reasonably make different choices.”

Noting that randomized trials on the benefits of screening have excluded women age 75 and older, the authors reviewed observational studies published between 1990 and 2014 to identify risk factors for late-life breast cancer and quantify the benefits and harms of screening for older women. They found that older patients often continue to undergo annual screenings automatically without discussing the potential benefits and harms with their physicians to help them making informed decisions based on their values.

The authors recommended that clinicians frame the discussion of whether or not to continue screening in terms of increasing harms relative to decreasing benefits. For example, follow-up procedures after false positive screenings, such as breast biopsies, can be more painful in women with arthritis or other medical problems and can be frightening for women with dementia.

In addition, screening exposes older women to risks associated with overdiagnosis, when a malignancy is detected during screening but is unlikely to become clinically significant during the patient’s lifetime. Women with a life expectancy of less than 10 years are more likely to die from other causes before they are affected by a screening-detected malignancy and may suffer unnecessary harms if they decide to undergo treatment, the authors said.

“To reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment requires finding ways to talk with women about these possibilities,” the authors said. “Most women want information about screening harms and in surveys, report that this knowledge would influence their decision-making.”

After explaining the potential harms of screening to women with shorter life expectancies, physicians should shift the focus to discussing health promotion strategies that could be effective over the short-term, the authors said.

When counseling women with a life expectancy of more than 10 years, physicians should emphasize that continued screening is a choice and inform them of the major benefits and harms. A decision should then be made based on the individual patient’s values and preferences.

The authors recommended that physicians cover the following key points when counseling older women about the choice to continue screening:

• Advancing age is the greatest risk factor for developing breast cancer.

• Observational studies suggest benefit of continued screening mammography in older women who have a life expectancy of more than 10 years.

• Potential harms of screening mammography include overdiagnosis as well as pain and anxiety associated with false positive results and biopsies.

• Breast cancer treatments are effective among older women in good health; however, the harms of breast cancer treatment increase as women age, particularly among older women with limited life expectancy.