Cancer Regression With Therapeutic HPV Vaccine

A new study has demonstrated that a therapeutic vaccine against HPV can stimulate an immune response and regression of high-grade cervical dysplasia, a precursor to cervical cancer in women with an HPV infection.

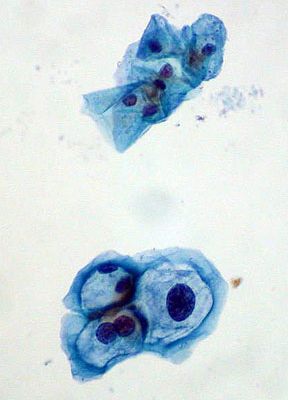

Normal squamous cells (top); HPV-infected cells with mild dysplasia (bottom)

A new study published in Science Translational Medicine has demonstrated that a therapeutic vaccine against the human papillomavirus (HPV) can stimulate an immune response and regression of high-grade cervical dysplasia, a precursor to cervical cancer in women with an HPV infection. Cornelia Liu Trimble, MD, associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, Leonel Maldonado, MD, of the department of gynecology and obstetrics, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore tested an intramuscular therapeutic vaccine and demonstrated that it was able to elicit a T cell response. Previous therapeutic HPV vaccines were thought to not work because there were no T cells against HPV antigens that could be detected in peripheral blood of patients-the standard signal that a vaccine has activity.

Rather than measuring T cells in the blood, the researchers measured T cell presence in the cervical tissue itself from 12 patients with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia from an HPV infection. After receiving the HPV vaccine, relatively high levels of HPV-targeted T cells were identified within the precancerous lesions despite low levels of such T cells in the circulation. This is the first study to identify a robust immune response to a therapeutic HPV vaccine, providing evidence that such vaccines could be used to treat high-grade cervical dysplasia caused by HPV infection in women.

“This finding suggests that it may be much more informative to look in the affected tissue than in the blood for immune responses, at least with the tools we have available now,” Dr. Trimble told Cancer Network. “We are very interested to see immune changes in the target lesions, after therapeutic vaccination.”

The target lesion microenvironment showed a three-fold increase in CD8-positive T cell infiltrates and both molecular and histologic changes. Cervical tissue after vaccination had organized lymphoid-like structures within the surrounding connecting tissue adjacent to the lesions. Compared with unvaccinated lesions, the vaccinated lesions had evidence of lymphoid cell proliferation. These histologic changes are known to be associated with better patient prognosis and paralleled molecular changes, including increased expression of immune activation genes such as CXCR3, IFNB, and TBET. The researchers also detected an immune signature within the dysplastic epithelium.

“These findings indicate that peripheral therapeutic vaccination to HPV antigens can induce a robust tissue-localized effector immune response, and that analyses of immune responses at sites of antigen are likely to be much more informative than analyses of cells that remain in the circulation,” concluded the authors.

The authors also noted that the number of CD8-positive infiltrates prior to vaccination was associated with the level of CD8-positive response after vaccination. The timing of peripheral blood draw and assessment for evidence of an immune response may be crucial for the ability to detect a circulating blood response, before the CD8-positive cells home to the site of antigen, according to the authors.

The therapeutic HPV vaccine used here targets the HPV16 E6/E7 antigens. Trimble and colleagues are currently working on the development of other HPV therapeutic vaccines. While the HPV preventive vaccine results in an antibody response to the HPV capsid protein, arming the body against an HPV infection before exposure to HPV, it is not able to treat an existing infection. In contrast, the goal of the therapeutic vaccination is to elicit an immune response that can target already infected cells, said Trimble.

The 12 otherwise healthy patients received two priming vaccinations, with a DNA vaccine expressing the HPV16 E7 antigen, twice every 4 weeks, followed by recombinant vaccinia boost that expressed HPV16 and HPV18 E6 and E7 antigens another 4 weeks later. Seven weeks after the boost vaccination, patients had a therapeutic resection of cervical tissue. The vaccine regimen was safe and tolerable. Patients were between 22 and 49 years of age.

About one-quarter of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasias caused by the virus serotype 16 spontaneously regress, but persistent HPV infection can cause cancers of the vagina, cervix, vulva, anus, and oropharynx, depending on the infection site. So far, it has been difficult to identify those patients whose high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasias are more likely to turn into cervical squamous cell carcinoma.

“HPV causes more cancers than any other virus,” said Trimble. “Infection is very common, in part because HPV does not harm most people who get an infection. A major question is how to identify whether a person is at risk for disease if they have an HPV infection.”

Trimble and colleagues are now trying to understand the signals required for an effective immune response to home to specific tissue and function on-site.