The carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet remains the chemotherapy backbone for the initial treatment of ovarian cancer. This two-drug regimen, with carboplatin dosed using the Calvert formula, yielded convincing noninferior outcomes when compared with the prior, more toxic, regimen of cisplatin/paclitaxel. Carboplatin’s dose-limiting toxicity is thrombocytopenia; however, when this drug is properly dosed and combined with paclitaxel, the doublet’s cycle 1 dose in chemotherapy-naive women is generally safe. Carboplatin (unlike cisplatin) contributes minimally to the cumulative sensory neuropathy of paclitaxel, thus ensuring noticeable reversibility of neuropathy symptoms following completion of 6 cycles and only occasionally requiring cessation or substitution of the taxane. Paclitaxel is responsible for the hair loss associated with the carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet; preventive measures must be considered for patients who would otherwise refuse treatment. Several first-line phase III trials, as well as ongoing trials for which only preliminary results have been published, have fueled debates on the optimal dose and schedule; these have focused not only on weekly vs q3-weeks paclitaxel, but also on other modifications and the advisability of adding bevacizumab. Our view is that results of this doublet in the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer are driven primarily by carboplatin, given that ovarian cancer is a platinum-sensitive disease. Consequently, the roles of the accompanying paclitaxel dose and schedule and the addition of bevacizumab are currently unsettled, and questions regarding these issues should be decided based on patient tolerance and comorbidities until additional data are available.

Introduction

The regimen consisting of carboplatin and paclitaxel represents the backbone of ovarian cancer treatment: 95% of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer will receive this regimen. It has been 15 years since the publication of the results of Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 158, an 840-patient noninferiority trial led by Robert Ozols that established carboplatin as a suitable replacement for cisplatin in the initial treatment of advanced ovarian cancer following primary debulking surgery.[1] Clinicians who treat gynecologic malignancies can recite chapter and verse about what is involved in administering the carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen and anticipating its toxicities. Despite our years of experience, including worldwide trials that use the original carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen as a control while exploring additions and dose/schedule modifications, we should not be lulled into believing that the majority of patients will sail through this therapy. Here, we reflect on our experience administering the carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen to scores of ovarian cancer patients over the past decade and a half. While some of these reflections represent our personal views, we hope what we have to say will help readers become more familiar with the key issues.

The successful combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel was the result of initial research efforts focused on the pharmacology of carboplatin and its clinical development that took place at the Royal Marsden Hospital/Institute of Cancer Research. These studies were led by Hilary Calvert, a disciple of Eve Wiltshaw, who had established cisplatin’s unprecedented activity in ovarian cancer.[2,3] The Calvert formula for dosing carboplatin, reinforced by the initial pharmacodynamic observations of Merrill Egorin and colleagues that focused on the drug’s dose-limiting toxicity of lowering platelet counts, became widely adopted as a reliable way of determining the maximum initial carboplatin dose that could be safely administered to chemotherapy-naive patients.[4,5]

Carboplatin’s usual doublet partner, paclitaxel, a water-insoluble compound first isolated from bark of the Pacific yew tree by the US Department of Agriculture for the National Cancer Institute, was introduced in the 1980s for clinical study in a formulation based on cremophor solubilization. Significant problems were encountered during laborious phase I trials: not only did paclitaxel require special tubing for its administration, but treatment also led to sudden deaths from anaphylaxis, resulting in cessation of its development. Development was not resumed until a combination of measures such as glucocorticoid premedication (given orally, starting the evening and morning before the first administration of paclitaxel) and lengthening of its administration yielded reproducible safety. Most importantly, these measures were coupled with outstanding nursing practices, such as observing patients carefully, especially during the first minutes of administration of the drug and periodically thereafter. Paclitaxel’s activity in ovarian cancer, initially demonstrated by William McGuire and colleagues, led to phase III trials that resulted in its displacing cyclophosphamide and other drugs in first-line combination regimens used in ovarian cancer treatment.[6,7]

The current treatment paradigm for patients with ovarian cancer continues to rely on a platinum/taxane doublet: the carboplatin/paclitaxel q21-days backbone used in GOG 158 has been the comparator arm for several trials attempting to improve on the original high response rates and more favorable progression-free and overall survival outcomes seen in the trial.[8] Even larger trials than GOG 158 tested mostly paclitaxel dose/schedule modifications or the addition of targeted drugs in attempts to improve on those original results. Leaving aside the controversy around intraperitoneal (IP) therapy for patients who have undergone successful cytoreduction to less than 1 cm of residual disease (recently discussed for ONCOLOGY by Keiichi Fujiwara and Robert Ozols[9]), we would like to comment on the paclitaxel dose/schedule alterations.

The Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG) studied weekly dosing of paclitaxel-a schedule that was optimal compared with the q3-weeks schedule in breast cancer for single–agent paclitaxel-and combined this with q21-days carboplatin. A striking survival advantage was observed, as well as impressive long-term results.[10,11] In a more recent GOG trial, the benefit of this weekly schedule was only observed in the minority of patients who did not receive bevacizumab in a q21-days schedule.[12] Other groups have reported on additional comparative trials; their results have added to the uncertainty surrounding paclitaxel dose/schedule alterations as a determinant of outcome in ovarian cancer. Tolerance is another aspect of such schedule changes that is important to consider; this will be the focus of the next several sections.

Hematologic Toxicity

Thrombocytopenia is the dose-limiting toxicity of carboplatin, and this was a principal consideration when Egorin and colleagues developed the initial pharmacodynamic dosing in a study that included patients with abnormal renal function.[13] Paclitaxel lessens the impact of carboplatin on platelet counts and actually speeds up recovery from platinum-induced marrow suppression-an effect that is particularly obvious when platinum/paclitaxel doublets are compared with other platinum doublets[6] or are used in previously treated patients.[14] It is unlikely that an area under the curve (AUC)-based first dose of carboplatin in a chemotherapy-naive patient will result in dose-limiting hematologic toxicity: platelet counts that drop below 50,000/μL and require platelet transfusions for bleeding in previously untreated patients are extremely uncommon events, particularly when carboplatin is administered in combination with paclitaxel. Because this carboplatin toxicity usually begins to appear after day 14 and is predictably cumulative, one should use the nadir platelet count of the preceding cycle and baseline upon recovery as signals to consider a carboplatin dose reduction. For example, if platelet counts are over 200,000/μL at the beginning of cycles 1 and 2, but are barely over 100,000/μL at the beginning of cycle 3, a pre-emptive dose adjustment that lowers the AUC by 20% is appropriate (even though this would not be called for by protocol adjustments that rely on drops below the normal range for platelet counts). Marrow tolerance in the preceding cycle (as determined by platelet nadir and recovery) is the best guide to dosing in the subsequent cycle; in fact, the absence of any effect on the platelet count is a signal that carboplatin may have been under-dosed. Moreover, if the platelet count does not fall to dose-limiting levels, it is unlikely that the patient will develop clinically significant neutropenia. A related corollary: granulocyte colony–stimulating factor administration is seldom, if ever, necessary in patients who are naive to chemotherapy.

Of course, paclitaxel is expected to add some myelosuppression of its own-and it does, particularly when given weekly. This and other practical aspects are reasons why the senior author has for years preferred a “divided-dose” regimen on days 1 and 11 of the cycle: if dosed at no higher than 100 mg/m2, paclitaxel’s effects on peripheral blood count nadirs (which usually occur on day 11±1) are transient, and perhaps lessen carboplatin-induced thrombocytopenia. As noted previously, paclitaxel accelerates bone marrow recovery, decreases platelet toxicity, and promotes the ability to give the next doublet cycle on time-likely enhancing the safety of this suggested “divided-dose” schedule.[15]

Neuropathy

Except in the case of weekly regimens, adjustments to the dose of paclitaxel are primarily made because of peripheral neuropathy. There are no clinically applicable quantifiable measures of sensory neuropathy, but analyses of randomized studies reinforce the relationship of neurotoxicity to taxane dose and schedule.[16] Encyclopedic listings of toxicities should not distract the clinician from the importance of personally monitoring sensory neuropathy-since this is the dose-limiting toxicity most commonly encountered in attempts to complete 6 cycles of treatment. Assessment of cycle-to-cycle patient-reported paresthesias is the most reliable way of detecting this problem early. Even though symptoms are not easily quantified, patients will often accurately describe their onset, location, and duration. Therefore, it cannot be sufficiently emphasized that caregivers must directly and routinely inquire about the extent and pattern of paresthesias. Continuous paresthesias during the entire interval between cycles should prompt implementation of dose reductions, and if the paresthesias reach a continuous level of grade 2, paclitaxel should be stopped. In the JGOG trial, weekly paclitaxel was associated with greater neuropathy than q3-weeks administration. It is notable that this remains the only first-line trial in which taxane dosing was a determinant of ovarian cancer survival. If it weren’t for this benefit, there would be little justification for continuing a neurotoxic drug when medication is required to ameliorate its symptoms (ie, ongoing grade 2 or higher neuropathy). In fact, neuropathy will invariably worsen for 2 to 3 weeks after paclitaxel is administered; it can eventually lead to impairment in activities of daily living that may be irreversible. Severe neuropathy after only 1 or 2 cycles is rare, but if this does occur, it may justify substituting docetaxel for paclitaxel. Beyond the early cycles, one may question whether the risk/benefit tradeoff associated with additional taxane dosing warrants continuation of the drug-especially considering that in first-line trials, platinums appeared to be the key determinant of outcome.[17,18] Therefore, stopping paclitaxel should be considered when there is persistent grade 2 neuropathy; clinical trial results reflect these sorts of protocol-driven dose adjustments and wide variations in taxane administration. In general, gabapentin should not be routinely used to suppress neuropathy symptoms, but this can be considered if symptoms interfere with sleep or daily activities. Also consider that pain resulting from growth factor support may be a confounder. Physicians need to allay patients’ fears about adjustments to the paclitaxel dose and reassure them that these are part of good clinical practice and unlikely to compromise survival.

The foregoing remarks about paclitaxel-associated sensory neuropathy were even more pertinent during the cisplatin era, because of the much greater neurologic damage resulting from cisplatin as opposed to carboplatin. Staggered doses of paclitaxel and cisplatin, with cisplatin given on the day following paclitaxel administration, would be expected to diminish the accelerated risk of sensory neuropathy by minimizing the pharmacologic interactions that would compound neuropathy risk. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), which lacks paclitaxel’s cremophor effect, offers yet another way of minimizing pharmacologic interactions of two drugs that may result in accelerating cumulative sensory neuropathy.[16,19]

Other Toxicities

Paclitaxel causes hair loss: this effect becomes manifest 3 weeks after administration of the drug and generally persists throughout treatment, with hair regrowth noted within 3 to 6 months of cessation of paclitaxel. Although it is almost always reversible, hair loss is one of the main reasons given for reduced quality of life by women treated with the carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen.[20] The late Syd Salmon introduced cold caps in the 1970s when doxorubicin was incorporated into the breast cancer armamentarium. Cold caps work by decreasing the temperature at the scalp; the resulting vasoconstriction and reduction in hair follicle metabolism reduce the effects of paclitaxel on the hair follicles. Although results vary, a large national registry in the Netherlands showed that up to 50% of scalp-cooled patients did not wear a head cover during their last taxane chemotherapy session.[21]

Carboplatin was developed in the early 1980s to overcome some of the serious toxicities of cisplatin. It markedly lowered the potential for nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and hyperemesis seen with cisplatin.[22] When tested by Bristol-Myers Squibb, carboplatin was the only platinum among a dozen nonnephrotoxic analogs that did not induce vomiting when administered to ferrets. Subsequent preclinical studies (in rats) of platinums and their interaction with membrane organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) demonstrated clearly that carboplatin-unlike cisplatin-interacts only minimally with OCT2 present in renal tubules and the cochlea.[23] One may generally reassure patients about the low risk of nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and hyperemesis with carboplatin, while on the other hand stressing its hematologic toxicities. However, one should underscore (as noted previously) that thrombocytopenia is the best indicator of carboplatin’s effects; this has been demonstrated not only by clinical trials, but also by Bristol-Myers Squibb databases.[5] Another major advantage of carboplatin over cisplatin, other than the favorable nonmarrow organ toxicity spectrum, is the much greater predictability of the former’s pharmacodynamic effects.

It is critical to spend time with the patient, personally reviewing the expected side effects of treatment. Printed information, while potentially useful as a resource, if not directly discussed at the outset, may promote unnecessary fears and may not adequately emphasize what to expect.

Other Recommended Practices When Treating With Carboplatin/Paclitaxel

While carboplatin/paclitaxel is a fairly easy doublet to administer, one should not underestimate the possibility of issues arising because of comorbidities and advanced cancer presentations. It is important to pay attention to the details of a patient’s history to help her get through the requisite number of cycles.

Before initiating treatment, one should ascertain whether corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, as they are in patients with active hepatitis, uncontrolled diabetes, or psychoses). Substitution of nab-paclitaxel for paclitaxel should be considered (but is dependent on access to this drug formulation). Use of nab-paclitaxel also overcomes difficulties with venous access and often makes it unnecessary to use central venous lines to deliver 6 cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel.

Going over a patient’s list of medications with an eye to stopping or replacing any that may potentially cause problems can be helpful. Possible problem medications include aspirin and diuretics. Aspirin may unnecessarily raise the risk of gastritis and bleeding, and may trigger unnecessary workup and, in the setting of a lower hemoglobin level, undue concerns about abdominal pain complicated by treatment-related anemia. When possible, substitute other classes of antihypertensives for diuretics, or consider intermittent use of loop diuretics. It is also wise to advise patients to reduce the number of pills they take, since any tablet or capsule intake may induce vomiting. Some of these practices are carryovers from cisplatin days, when electrolyte imbalances were common, but they do apply to a certain extent to carboplatin.

Specific Comments on the Ongoing Carboplatin and Paclitaxel Scheduling Debates

1. Do not focus on the white blood cell count and the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) except when a patient is febrile or pancytopenic (including a low platelet count); remember that the platelet count is the major indicator of carboplatin toxicity. One can redose the doublet when the ANC is below 1,000 cells/μL as long as the platelet count has shown brisk recovery and the absolute monocyte count plus the ANC total 1,000/μL (monocytes are a sign of rebounding marrow, and so is the increase in platelets that occurs as the number of white cells dips). In fact, the divided-dose regimen[15] documents such patterns better by dosing at the paclitaxel ANC nadir; this regimen may also allow better titration of drug doses.

KEY POINTS

- Carboplatin is the key drug of the carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet, and is most accurately dosed using the Calvert formula.

- Adjusting the dose of carboplatin requires that the clinician be mindful of baseline and nadir platelet counts; neutropenia has few consequences unless preceded by severe thrombocytopenia.

- Questions regarding the optimal dose and schedule for paclitaxel are part of an ongoing debate, with recent trials addressing these issues.

2. Weekly carboplatin, validated as noninferior to q3-weeks carboplatin in the recent ICON8 trial, requires further discussion upon publication of the trial’s full results. The senior author has seen instances where physicians were confused about continued dosing: they were uncertain which agent was contributing to observed hematologic changes, or which agent was the culprit when a rash raised concerns of hypersensitivity. In addition, the required weekly antiemetics may wreak havoc with a patient’s bowels, as well as causing other problems. (Note: paclitaxel as a single agent only requires small doses of dexamethasone to protect against its mild associated nausea-if any.)

3. Weekly paclitaxel regimens need to undergo frequent modifications in dose or require the addition of growth factor support. We recently published data on patient tolerance of a divided-dose paclitaxel schedule that we were using prior to publication of the JGOG studies on weekly paclitaxel; under certain circumstances there were concerns of intolerance of the higher paclitaxel doses, such as in frail patients with advanced presentations requiring neoadjuvant chemotherapy.[15]

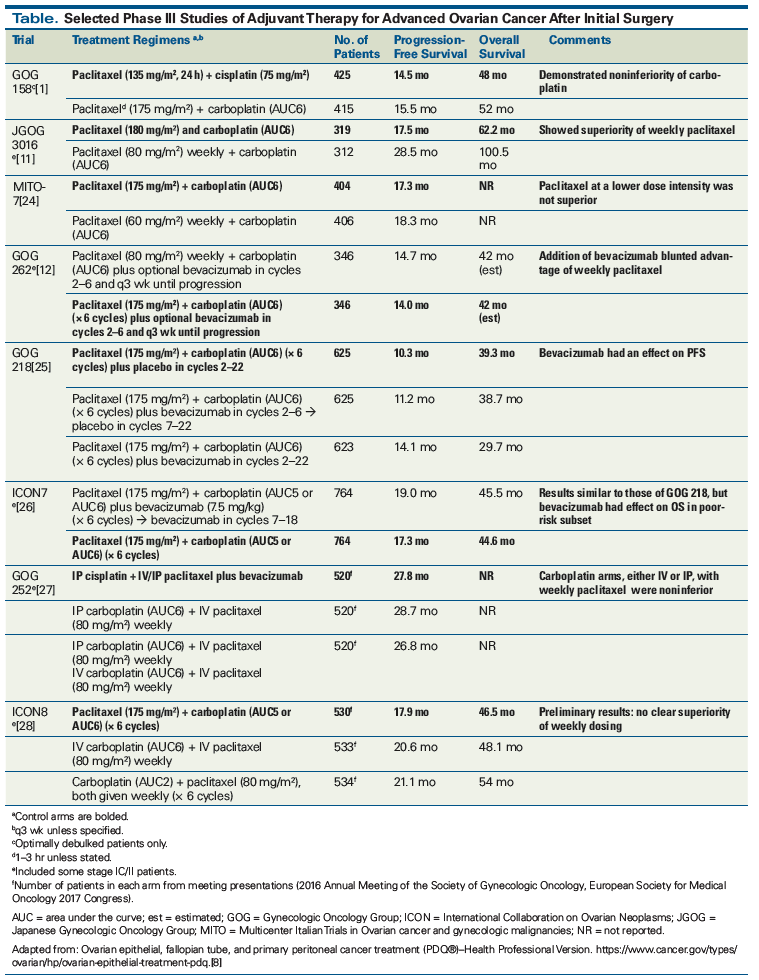

4. The Table summarizes median progression-free survival and overall survival data from worldwide phase III trials, starting with the GOG 158 noninferiority trial that resulted in carboplatin displacing cisplatin in the upfront platinum doublet. The outstanding results of JGOG 3016 made the weekly paclitaxel regimen the front-runner, but these results were not replicated by MITO-7 (perhaps because of the lower dose of paclitaxel used) or by GOG 262 (which only showed an advantage for the weekly regimen when bevacizumab was not used). The recent publication of ICON8 adds another wrinkle to the debate: this trial appears to validate the use of weekly dosing for both carboplatin and paclitaxel. Full publication of the ICON8 data is needed before changes in schedule and in route of administration, such as those represented by the GOG 252 results, can be incorporated into treatment guidelines.

Conclusion

Since the publication of GOG 158, the IV carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet × 6 cycles has become the standard chemotherapy backbone for ovarian cancer patients after primary surgical debulking. Phase III trials in which bevacizumab has been added to both IP and IV standard regimens have raised doubts about the advantages of the IP route for optimally cytoreduced patients, and about the weekly paclitaxel schedule for all others. Full publication of these well-conducted trials is awaited before guidelines are adopted for issues surrounding the carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet. Debates are ongoing about the optimal schedule and route of administration, and the question of whether to add bevacizumab. However, oncologists should be familiar with expected toxicities such as neuropathy and hair loss, as well as knowledgeable about strategies for adjusting carboplatin dosing so as to maximize benefit and minimize the risk of cytopenias and the need for growth factors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no significant financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

1. Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194-200.

2. Wiltshaw E, Kroner T. Phase II study of cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum (II)(NSC-119875) in advanced adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Treat Rep. 1976;60:55-60.

3. Rozencweig M, Von Hoff DD, Slavik M, Muggia FM. Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (DDPP): a new anticancer drug. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:803-12.

4. Calvert AH, Newell DR, Gumbrell LA, et al. Carboplatin dosage: prospective evaluation of a simple formula based on renal function. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1748-56.

5. Jodrell DI, Egorin MJ, Canetta RM, et al. Relationships between carboplatin exposure and tumor response and toxicity in patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:520-8.

6. McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1-6.

7. Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, et al. Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:699-708.

8. Ovarian epithelial, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. https://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian/hp/ovarian-epithelial-treatment-pdq. Accessed July 10, 2018.

9. Fujiwara K, Ozols R. Point/counterpoint. Is there still a role for intraperitoneal platinum therapy in ovarian cancer? Oncology (Williston Park). 2018;32:75-9.

10. Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, et al. Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1331-8.

11. Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Isinoshi S, et al. Long-term results of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin versus conventional paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (JGOG 3016): a randomized, controlled open-label trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1020-6.

12. Chan J, Brady MF, Penson RT, et al. Weekly vs every-3-week paclitaxel and carboplatin for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:738-48.

13. Egorin MJ, Van Echo DA, Tipping SJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosage reduction of cis-diammine (1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylato) platinum in patients with impaired renal function. Cancer Res. 1984;44:5432-8.

14. Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099-106.

15. Kudlowitz D, Velastegui A, Musa F, Muggia F. Carboplatin (every 21 days) and divided-dose paclitaxel (days 1, 11): rationale and tolerance in chemotherapy-naïve women with high-grade epithelial cancers of Mullerian origin. Cancer Chemother Pharm. 2018 Mar 7. [epub ahead of print]

16. Kudlowitz D, Muggia F. Defining risks of taxane neuropathy: insights from randomized clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4570-7.

17. Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, et al. Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:106-15.

18. The International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505-15.

19. Kudlowitz D, Muggia F. Clinical features of taxane neuropathy. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:495-501.

20. Brundage M, Gropp M, Mefti M, et al. Health-related quality of life in recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer-results of the CALYPSO trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2020-7.

21. van den Hurk CJ, Peerbooms M, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Scalp cooling for hair preservation and associated characteristics in 1411 chemotherapy patients-results of the Dutch Scalp Cooling Registry. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:497-504.

22. Muggia FM, Bonetti A, Hoeschele JD, et al. Platinum antitumor complexes: 50 years since Barnett Rosenberg’s discovery. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4219-26.

23. Ciarimboli G. Membrane transporters as mediators of cisplatin side-effects. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:547-50.

24. Pignata S, Scambia G, Katsaros D, et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel once a week versus every 3 weeks in patients with advanced ovarian cancer (MITO-7): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:396-405.

25. Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473-83.

26. Perren TJ, Swan AM, Pfisterer J, et al; ICON7 investigators. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484-96.

27. Walker JL, Brady MF, DiSilvestro PA, et al. A phase III clinical trial of bevacizumab with IV versus IP chemotherapy in ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinoma: an NRG Oncology study. Presented at: 47th Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology; March 19–22, 2016; San Diego, CA. Abstract LBA6.

28. Clamp AR, McNeish I, Dean A, et al. ICON8: a GCIG phase III randomized trial evaluating weekly dose-dense chemotherapy integration in the first-line epithelial ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal carcinoma treatment: results of primary progression-free survival analysis. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5 suppl):v605-v649.