Chemo Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Has Genetic Basis

Researchers have found that tumors with multiple cancer genomes and the downregulation of the LRP1B gene are associated with chemotherapy resistance among patients with the high-grade serous ovarian cancer.

Researchers have found two characteristics that may contribute to chemotherapy resistance among ovarian cancer patients. David Bowtell, PhD, of the Cancer Genomics and Genetic Program at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, and colleagues sequenced and analyzed patient tumors in an attempt to identify factors responsible for chemotherapy resistance. The study authors found that ovarian tumors with multiple cancer genomes in an individual patient, and downregulation of a gene called LRP1B are associated with resistance to chemotherapy in women with high-grade serous (HGSC) ovarian cancer. The study is published in Cancer Research.

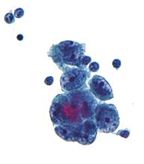

Micrograph showing serous carcinoma. Peritoneal fluid specimen. Source: Nephron, Wikimedia Commons

The most important takeaways from the study are the extent of clonal variation in high-grade serous cancer and that the cancer genome does indeed evolve during therapy, according to Bowtell.

Ovarian cancer is diagnosed in approximately 22,280 women every year in the United States, and 15,500 women die of the disease annually-the cancer ranks fifth among all cancer deaths in women. It is typically diagnosed in advanced stages of disease and because the disease is histologically diverse, it is difficult to treat.

Standard of care is cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy, which has not significantly improved long-term survival. While most advanced HGSC initially responds to chemotherapy, the majority of patients eventually relapse as a result of chemotherapy resistance. According to the authors, HGSC accounts for two-thirds of deaths from invasive ovarian cancer.

Identification of molecular or cytologic subcategories of ovarian cancer to better tailor treatment has been difficult. HGSC has a high level of genomic instability, DNA copy number fluctuations, and intratumor heterogeneity, making it difficult to characterize and identify drug targets. Bowtell points out that ovarian cancer is particularly difficult to characterize. “High-grade serous share an interesting molecular and clinical relationship with triple-negative breast cancer.”

While many women with HGSC ovarian cancer initially respond well to treatment, recurrence is frequent and there is currently no substantial way to predict which patients will respond and which patients should side-step chemotherapy for other options. “If we can comprehensively map the mechanisms that confer resistance, we may be able to predict whether some women are likely to respond to a certain drug or not, and find ways of reversing resistance,” said Bowtell.

The authors analyzed metastatic tumor tissue samples, pre- and post-treatment, of 22 women to identify how the cancer genome evolved due to cancer therapy. The researchers also analyzed different samples from different parts of the tumor to assess the heterogeneity of the tumor at a single point in time.

Comparing the genomic changes in women who were initially sensitive to chemotherapy compared to those who were resistant to chemotherapy from their initial treatment. The analysis found those tumors that were initially sensitive but became resistant post-treatment evolved more genetically compared to those that were resistant initially.

“We were surprised by the extent of variation that was present among the tumor deposits collected at surgery, and by how far the tumors could evolve during therapy,” Bowtell said. “The existence of multiple cancer genomes in an individual patient could provide many opportunities for the cancer to circumvent chemotherapy and may help explain why it has been so difficult to make progress with this disease,” he said.

In the authors' analysis, deletion or downregulation of the lipid transporter LRP1B was significantly associated with acquired resistance. The finding that mutation of LRP1B is associated with acquired resistance post–chemotherapy treatment was validated using a sample of 92 other tumor samples. LRP1B is a putative tumor suppressor gene-deletions of the lipid transporter LRP1B and missense mutations in the gene have been documented in other solid tumors. Further validation using ovarian cancer cell lines showed that LRP1B overexpression increased sensitivity to liposomal doxorubicin, but reducing LRP1B expression reduced the sensitivity of HGSC cell lines to liposomal doxorubicin (but not to doxorubicin).

Next Steps

A trial to study reverse platinum resistance in the relapse setting is going to begin shortly, says Bowtell. “We need a comprehensive map of all the mechanisms of drug resistance in the relapse setting-more samples and analysis,” says Bowtell, whose research is part of the International Cancer Genome Consortium. One of the goals is to map emergent resistant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer as well as other solid tumors.

Bowtell is optimistic that with considerable research, the field will be able to characterize subsets of ovarian cancer that are most likely to respond to chemotherapy and other agents. “We need to better understand adaption [of the cancer to treatment], but that could happen quite quickly,” Bowtell said. “As we have seen in lung and other solid cancers, if there is a druggable target, trials can happen quite quickly.”