Dr. Hussey Foresees More Physician Competency Reviews

BOSTON-David H. Hussey, MD, president of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO), predicts that increased assessment of physician competence will have a profound and positive effect on medical training for new and practicing physicians in all medical specialties.

BOSTONDavid H. Hussey, MD, president of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO), predicts that increased assessment of physician competence will have a profound and positive effect on medical training for new and practicing physicians in all medical specialties.

Its like a train coming down the track. Its not going to be something that you or I will be able to change, he told physicians at ASTROs annual meeting.

The American Board of Radiology (ABR) has offered certification in therapeutic radiology since it was formed in 1934. Radiation oncology first became popular as a specialty in the late 1960s. By June 2000, 4,009 physicians were board certified in therapeutic radiology or radiation oncology.

In 1995, the board began offering 10-year certificates in radiation oncology. As a result, all radiation oncologists certified after 1994 must be recertified every 10 yearsbut not those who were certified earlier and have lifelong certification.

The board offered the first recertification exam in 1999 and will offer another test some time between February and April 2001 in Tucson, Tampa, Chicago, and Dallas. This will be the last time it will be offered at no charge.

More than 250 radiation oncologists have taken the clinically oriented radiation oncology examination so far, and the pass rate has been very high, said Dr. Hussey, who is currently on sabbatical at the ABR. He has been a faculty member at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City.

Maintenance of Certification

While some critics say repeated competency testing is unnecessary, these exams are the beginning, not the end, of a stepped-up review process, Dr. Hussey said. He advised ASTRO members to expect additional assessments of physician competence, and predicted that the next step will be maintenance of certification, an approach that is broader in scope than re-certification examinations and is continuous rather than periodic.

The American Board of Medical Specialties has identified four components of the maintenance of certification process, which Dr. Hussey listed with examples of how they might be applied:

1. Cognitive expertiseThis is, basically, a re-certification exam.

2. Commitment to lifelong learningThis involves earning continuing medical education credits, but only for those courses deemed relevant to the certification.

3. Professional standingThe physician must have a valid license, plus undergo periodic peer examination and review of clinical privileges.

4. Practice performanceThis could include chart audits, if not too expensive, and/or review by an oversight committee independent of member societies.

Board Certification

Dr. Hussey presented the current board certification process as a model of what physician assessment has to offer the medical profession. Certifying boards serve three functions. Theyre a hurdle, a teaching tool, and a learning tool, he said. They set standards not just for physicians but also for training programs that must prepare physicians to be able to pass board examinations.

As a hurdle, they are not that effective, he quipped, reporting that 91% of all who applied from 1990 to 1995 have received board certification. The strength of certification exams, he said, is that they provide an incentive for learning.

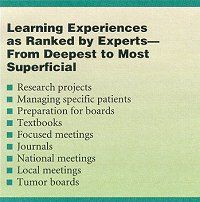

In preparation for ASTRO, Dr. Hussey said, he asked a group of experts to rank educational venues according to the depth of the learning experience. The experts, who were mainly ASTRO leaders and educators, ranked preparing for boards in the top three deep-learning experi-encesafter research projects and managing specific patients. National meetings, such as the ASTRO meeting, did not fare as well; only local meetings and tumor boards were described as more superficial (see Table).

The ranking makes sense, Dr. Hussey said. If a resident does a research project on minor salivary gland tumors, for example, odds are that that resident knows that subject as well as most expertsand that knowledge will stay with him as long as he lives, he said.

Likewise, he said, preparing for boards is a deep learning experience because of the intensity of the review process and the need to conceptualize in order to learn a large amount of information.

Certifying boards can set higher standards than licensing boards because board certification is a voluntary process, he said. You dont need to be certified to practice radiation oncology, whereas a physician does have to be licensed to practice medicine, he said. You dont want to take away someones right to practice unless you are absolutely sure they dont measure up. Besides, an adverse action could lead to a lawsuit. Since boards dont affect the right to practice, they can set the bar higher without fear of lawsuits.

Accreditation

Using the same line of reasoning, accreditation simply means a residency program has met minimally acceptable standards. You dont want to take away an institutions right to have a residency program unless you are absolutely sure they dont measure up, he said.

Rating residency programs as A, B, C, D, or F would be better than the current all-or-nothing system, Dr. Hussey said. He suggested one endpoint might be based on the percentage of first-time candidates who passed oral and written exams without difficulty over the last 10 years. Among 76 programs, this ranges from a high of 93% to a low of 0%. He predicted that objections to a grading system would come not from failing institutions but from institutions that would not want to risk slipping from A to B.

Dr. Hussey was generally positive about the board examinations currently offered, although he predicted that they too would change. There are four levels of performance assessment, he said. One can assess if the physician knows, knows how, shows how, or does. What the public is interested in is does. At present, none of the exams test that.

Nonetheless, the written exam is a good, inexpensive way to test the candidates knowledge base, he said, and the oral test is a good measure of deductive reasoning and clinical skills.

But the oral exam also has shortcomings, Dr. Hussey said: It is subjective, time-consuming, and expensive. We have to bring 60 examiners to Louisville each year just to give the exam, he said.

He predicted that in the exams of the future, candidates will interact with computers just as they would with an examiner, answering questions about clinical situations, outlining tumors, and drawing treatment portals on screen. Personalities would not influence scores, costs would be less, and the exam could be given several times a year at multiple locations. A very powerful computer program has been developed that can score degrees of error, Dr. Hussey said, distinguishing an answer that is way off from one that is close.

For now, the recertification exam in radiation oncology is a general exam, Dr. Hussey, but it might be replaced by a series of subspecialty exams. The problems would be keeping different subspe-cialties equal, he said, and What do you do about the physician who only wants to study one subject even though his practice covers all aspects?

So far, the high overall pass rate attests to the knowledge of radiation oncologists today, Dr. Hussey said. Nevertheless, he concluded, the public wants greater oversight. Every other effort to assess the quality of training and the competence of physicians has had a positive impact on patient care, and I dont see why this should be any different.