PERSPECTIVE BY

Nancy E. Mills, MD, FACP

Dual HER2 Targeting in the Adjuvant Setting Remains Controversial

This article discusses the advances in HER2-targeted therapy, in both the metastatic and adjuvant settings, with a focus on those with early-stage breast cancer.

Oncology (Williston Park). 32(10):483-7.

Anureet C. Copeland, MD

Carey K. Anders, MD

Figure 1. HER2 activates several signaling pathways in the ErbB family of receptors

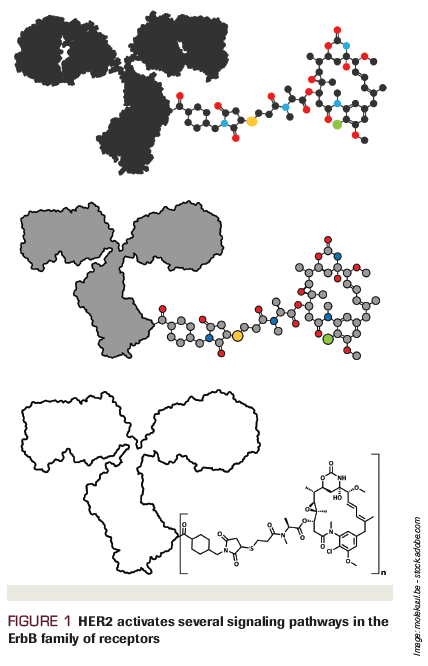

Figure 2. Main HER2 dimers and close-up structure

Figure 3. HER2 is prolific in up to 30% of breast cancers

Adjuvant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-directed treatment has changed dramatically over the past decade. Historically, the addition of 1 year of trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy has significantly improved both disease-free survival and overall survival across several studies. More recently, and in the metastatic setting, dual HER2-targeted therapy-beyond that of trastuzumab alone, and in combination with monoclonal antibodies such as pertuzumab and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as lapatinib-has shown a survival benefit. As is common in drug development, promising agents in the metastatic setting are then examined in the curative setting. This article will provide an overview of the efficacy of dual HER2-targeted therapy in the adjuvant setting as reported in the APHINITY, ExteNET, and ALTTO trials. Potential toxicities with dual HER2-targeted therapy and the financial consequences of adding additional HER2-targeted therapy, beyond trastuzumab, in the adjuvant setting will also be discussed.

Over the past decade, adjuvant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted therapy has transformed considerably. HER2-directed systemic therapy has dramatically altered the prognosis of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. The development of HER2-directed monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has improved the natural history of HER2-positive disease. This article discusses the advances in HER2-targeted therapy, in both the metastatic and adjuvant settings, with a focus on those with early-stage breast cancer.

Adjuvant HER2-targeted therapy was initially examined in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials.[1,2] N9831 was a phase III trial that enrolled patients with HER2-positive, node-positive, or high-risk node-negative disease. Patients received 4 cycles of adjuvant doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) followed by treatment in one of the three arms: weekly paclitaxel for 12 weeks (control arm), paclitaxel followed by trastuzumab for 52 weeks, or weekly paclitaxel given with trastuzumab for 12 weeks followed by trastuzumab alone to complete a total of 52 weeks. B-31 was a two-arm phase III trial in which patients received AC followed by 4 cycles of paclitaxel alone or 4 cycles of paclitaxel plus weekly trastuzumab to complete a total of 52 weeks.

Combined analysis of N9831 and B-31 demonstrated that adding 1 year of trastuzumab to standard anthracycline plus taxane–based adjuvant chemotherapy improved disease-free survival (DFS; hazard ratio [HR], 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53−0.68; P < .001) and overall survival (OS; HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54−0.73; P < .001) at 10 years.[3] The HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial, which assigned women to 1 year of trastuzumab vs observation after completion of adjuvant therapy, also showed improved DFS (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68−0.86) and OS (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.64−0.86) at 11 years.[4]

The optimal duration of trastuzumab has been studied in the HERA and PHARE (Protocol for Herceptin as Adjuvant Therapy with Reduced Exposure) trials. HERA, an international randomized trial that assigned patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer to 1 vs 2 years of adjuvant trastuzumab, showed no improvement in DFS with the longer duration (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.89–1.17); increased rates of cardiac toxicity were observed in the 2-year arm compared with the 1-year arm (7.3% vs 4.4%).[5] PHARE demonstrated that 6 months of trastuzumab was inferior to 12 months, with increased distant recurrence events (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04–1.71) and deaths (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.06–2.01) in the 6-month arm.[6]

The Short-HER study randomized patients to 1 year of trastuzumab vs 9 weeks of trastuzumab. Researchers enrolled patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and node-positive or high-risk node-negative disease. The shorter duration of trastuzumab was noninferior to the longer duration, with an HR of 1.15. Additionally, there was no difference in the OS rate at 5 years (95.1% vs 95% in the longer and shorter groups, respectively). In subset analysis, patients with stage III disease or those with multiple positive lymph nodes benefited from the longer duration of treatment.[7]

As is common in drug development, novel strategies like dual HER2-targeted approaches were first explored in the metastatic patient population and demonstrated notable efficacy. Pertuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the extracellular domain II of HER2, blocking heterodimerization of HER2 with other HER receptors, namely HER3, leading to inhibition of downstream signaling pathways.[8]

The phase III CLEOPATRA trial looked at the efficacy of dual HER2 inhibition with the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab with docetaxel in the first-line treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer. Patients were randomized to docetaxel and trastuzumab plus placebo or docetaxel and trastuzumab plus pertuzumab. CLEOPATRA showed a significant improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS) of 18.5 months in the pertuzumab group vs 12.4 months in the control group (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.51−0.75; P < .001).[9] Median OS was 56.5 months in the pertuzumab group (95% CI, 49.3 months−not reached) compared with 40.8 months in the control group (95% CI, 35.8−48.3 months).[10]

In addition to monoclonal antibodies, HER2-directed TKIs have also changed the landscape of HER2-positive breast cancer. Lapatinib is a reversible small-molecule inhibitor that binds to the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of HER1 and HER2.[11] EGF104900, a multicenter, phase III, open-label trial, showed that the combination of lapatinib plus trastuzumab vs lapatinib alone improved PFS (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58−0.94; P = .011) and OS (benefit of 4.5 months; HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57−0.97; P = .026) in patients with metastatic disease.[12,13] Neratinib, an irreversible small-molecule TKI of the HER1 and HER2 receptors, has also been studied in the HER2-positive setting. Burstein et al showed that neratinib demonstrated a durable clinical benefit in patients with metastatic breast cancer, who were both trastuzumab-pretreated and trastuzumab-naive.[14] Median PFS for the groups was 22.3 and 39.6 weeks, respectively.[14]

Given the success of dual HER2-targeted therapy in the metastatic setting, the efficacy of this approach has more recently been reported in the adjuvant setting. Historically, the addition of trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer has significantly improved DFS.[15] The APHINITY trial looked at adding a second HER2-directed agent, pertuzumab, to trastuzumab postoperatively in women with HER2-positive disease. More than 4,800 women were randomized to receive 18 weeks of standard-of-care chemotherapy with trastuzumab plus placebo or trastuzumab plus pertuzumab for 1 year. At 3 years, 94.1% of patients in the trastuzumab plus pertuzumab arm were disease-free compared with 93.2% in the trastuzumab plus placebo arm (HR for an invasive event, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66−1.00; P = .045).

In a subset analysis of patients with node-positive disease, the 3-year DFS rate was 92% in the pertuzumab arm compared with 90.2% in the placebo arm (HR for invasive event, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.62−0.96; P = .02). Additionally, in the cohort with hormone receptor (HR)-negative disease, the 3-year DFS rate was 92.8% in the pertuzumab arm and 91.2% in the placebo arm (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.56−1.04; P = .08). At 3-year follow-up, there was an absolute benefit of 0.9% for DFS favoring pertuzumab. Additionally, distant recurrences were fewer in the pertuzumab arm (4.7% vs 5.8% in placebo arm; P = .101). These results indicate a modest benefit for a dual HER2-targeted approach in the adjuvant setting, particularly in patients with higher-risk disease (eg, node-positive or HR-negative disease).[16]

How does dual monoclonal antibody HER2-directed therapy compare with the addition of HER2-directed TKIs to trastuzumab? The ExteNET study evaluated the addition of neratinib for 1 year vs placebo in patients with stage I–IIIc HER2-positive breast cancer who were previously treated with 1 year of trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. Patients had no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease at enrollment. At 5 years, the DFS rate was 90.2% in the neratinib group and 87.7% in the placebo group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57–0.92; P = .0083). Interestingly, in subset analysis, the HR-positive cohort derived greater DFS benefit (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43–0.83) from the additional of neratinib as compared with the HR-negative cohort (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.66 – 1.35).[17]

The phase III ALTTO trial compared the efficacy of the addition of lapatinib to trastuzumab (sequentially after completion of 12 weeks of trastuzumab or concurrently with 52 weeks of trastuzumab) vs trastuzumab alone for 1 year in 8,000 patients. A fourth arm of lapatinib alone was closed early due to futility. Comparing 6-year DFS between treatment groups, the HR was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.74–1.00) for lapatinib plus trastuzumab vs trastuzumab alone; the HR was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.81–1.08) for trastuzumab followed by lapatinib sequentially vs trastuzumab alone. No difference was seen for OS between groups. In subgroup analysis, those with HR-negative disease derived the greatest DFS benefit from dual therapy (a 4% absolute benefit).[18,19]

With the addition of HER2-directed agents in the adjuvant setting, clinicians must consider potential toxicities, with gastrointestinal and cardiac adverse effects emerging as the most significant sequelae. In APHINITY, the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab led to primary cardiac events in 9 additional patients compared with trastuzumab alone, but occurrences were still low (0.7% in the pertuzumab arm and 0.3% in the placebo arm).[16] Grade 3 diarrhea was more commonly seen with pertuzumab.

In the ALTTO trial, more cardiac events occurred in the trastuzumab-alone arm compared with the lapatinib-containing arms (11% (T) vs 9% (L+T) and 7% (TâL), respectively); however, fewer events in the trastuzumab-only arm were deemed to be serious cardiac events.[18] In the ExteNET trial, diarrhea was the most common adverse effect from neratinib, with 40% of patients reporting grade 3 diarrhea at the 2-year follow-up.[17] Finally, in the Short-HER study, there were fewer cardiac events in the shorter arm (9 weeks) vs the longer arm (12 months) of trastuzumab (5.1% vs 14.4%, respectively); however, the majority of these events were grade 2 in nature.[7]

Nancy E. Mills, MD, FACP

Dual HER2 Targeting in the Adjuvant Setting Remains Controversial

Drs. Copeland and Anders’ main point is that there is no “one size fits all” for breast cancer patients who require adjuvant therapy, and that individualized decisions must be made, weighing risks and benefits for each patient.

Even in the highest-risk patients, for whom the evidence does show benefit from the dual-antibody approach, the APHINITY trial showed those benefits to be somewhat modest. Therefore, issues regarding toxicity must be taken into account. The main toxicities to keep in mind are cardiac and gastrointestinal, most notably diarrhea. Oncologists are obligated to discuss these issues with patients before embarking on dual-antibody therapies.The addition of 1 year of neratinib, as per the ExteNET trial, is also a decision that needs to be individualized. Data suggest a potential benefit in high-risk patients, but there is a significant probability that marked diarrhea will occur. Moreover, the patients in ExteNET did not receive adjuvant pertuzumab, making it difficult to know whether there is any benefit to neratinib for those who did receive pertuzumab. These patients also tend to be the highest-risk patients.Thus, given the potential for toxicity and the somewhat modest benefits, the use of dual HER2 targeting in the adjuvant setting remains somewhat controversial. The best approach to ensure appropriate use of dual HER2 targeting as adjuvant therapy in breast cancer is one in which the clinician and patient discuss all options in terms of risks, benefits, and quality of life.Dr. Mills is a Medical Oncologist and Director of Cancer Survivorship at New York Presbyterian Lawrence Hospital Cancer Center in Bronxville, New York and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York

When considering all aspects of dual HER2-targeted therapy in the adjuvant setting, providers must also consider the financial implications. Standard adjuvant trastuzumab averages $55,000 USD per patient annually, based on US Medicare data.[20,21] As expected, the addition of dual HER2-targeted therapies results in increased cost compared with trastuzumab alone. The addition of 1 year of pertuzumab to trastuzumab results in an additional $95,000 USD per patient, while 1 year of lapatinib increases the cost by $42,000 USD.[20] Decreasing the duration of trastuzumab to 9 weeks, per Short-HER data, would reduce costs by nearly $45,000 USD per patient annually.[20]

To place these costs into the larger context of historical modifications to standard-of-care adjuvant treatment, 4 cycles of adjuvant paclitaxel added to AC increases costs by $12,500 USD per patient, while extension of aromatase inhibitor treatment from 5 years to 10 years adds approximately $15,000 USD per patient.[20] Today, we are faced with the challenge of providing exceptional individualized care utilizing newer HER2-directed therapies in an era in which healthcare costs continue to substantially increase. Careful balance between risk, benefit, and financial toxicity must be considered when making decisions about adjuvant HER2-directed therapy.

In summary, systemic therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer patients has changed remarkably over the last several years. As clinicians consider the use of HER2-targeted agents in the adjuvant setting for early-stage disease, an approach tailored to individual risks and benefits must be taken into consideration. We are no longer in a “one size fits all” scenario. In lower-risk patients with node-negative, HR-positive disease, treatment with chemotherapy plus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab is appropriate. For higher-risk patients with node-positive or HR-negative disease, 1 year of dual HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab with pertuzumab) in combination with chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting can be considered. In the adjuvant setting for higher-risk, node-positive, HR-positive disease, it may be reasonable to consider adding 1 year of neratinib after 1 year of trastuzumab based on ExteNET data. Finally, with regards to the duration of HER2-directed therapy, we still recommend 1 year of adjuvant therapy; however, in those with high-risk cardiac disease who experience a reduction in ejection fraction while on therapy, the Short-HER data do give us some reassurance that there is benefit from a shorter duration of HER2-directed therapy. Finally, when making all of the above decisions, we as a medical community must consider the financial toxicities as they relate to our global health economy, as well as the sustainability of such approaches.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Anders receives research funding from Cascadian, Genentech, GI-Therapeutics, Lily, Merck, Merrimack, Nektar, Novartis, Puma, Seattle Genetics, and Tesaro. Dr. Copeland has no significant financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

1. Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673-84.

2. Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Four-year follow-up of trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: joint analysis of data from NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3366-73.

3. Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3744-52.

4. Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, et al. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;389:1195-205.

5. Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, et al. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;389:1195-205.

6. Pivot X, Romieu G, Debled M, et al. 6 months versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHARE): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:741-8.

7. Conte P, Frassoldati A, Bisagni G, et al. 9 weeks vs 1 year adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy: final results of the phase III randomized Short-HER study. Ann Oncol. 2018 Sep 13. [Epub ahead of print]

8. Baselga J, Swain SM. Novel anticancer targets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:463-75.

9. Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109-19.

10. Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724-34.

11. Tevaarwerk AJ, Kolesar JM. Lapatinib: a small-molecule inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinases used in the treatment of breast cancer. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2332-48.

12. Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, et al. Randomized study of lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1124-30.

13. Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, et al. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585-92.

14. Burstein HJ, Sun Y, Dirix LY, et al. Neratinib, an irreversible ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced ErbB2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1301-7.

15. Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659-72.

16. von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:122-31.

17. Martin M, Holmes FA, Ejlertsen B, et al. Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): 5-year analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1688-700.

18. Moreno-Aspitia A, Holmes EM, Jackisch C, et al. Updated results from the phase III ALTTO trial (BIG 2-06; NCCTG (Alliance) N063D) comparing one year of anti-HER2 therapy with lapatinib alone (L), trastuzumab alone (T), their sequence (T→L) or their combination (L+T) in the adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl):abstr 502.

19. Piccart-Gebhart M, Holmes E, Baselga J, et al. Adjuvant lapatinib and trastuzumab for early human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III adjuvant lapatinib and/or trastuzumab treatment optimization trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1034-42.

20. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Price and value of cancer drug. https://www.mskcc.org/research-areas/programs-centers/health-policy-outcomes/cost-drugs. Accessed September 15, 2018.

21. Bach PB. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:626-33.