Metastatic Prostate Cancer Patients Respond to PARP Inhibitor

Men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had mutations in DNA repair genes were more likely to respond to the PARP inhibitor olaparib.

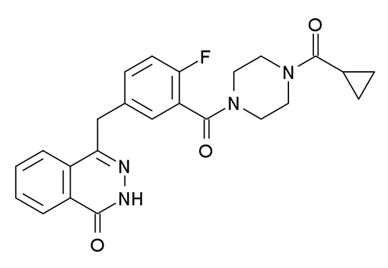

Chemical structure of olaparib

Men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) that had mutations in DNA repair genes were more likely to respond to the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib. In the phase II TOPARP trial, 17 of the 49 evaluable men responded to olaparib. Six men had radiologic responses and 11 had biochemical responses, as determined by a reduction in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels of greater than 50%. Four of these patients had responses that lasted more than 12 months.

The results were presented at a press briefing at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting, held April 18 to 22 in Philadelphia.

Joaquin Mateo, MD, a clinical research fellow in the Prostate Targeted Therapy Group and Drug Development Unit at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, and colleagues used next-generation sequencing to detect mutations-both somatic and germline-in genes associated with DNA repair. Mutations in these genes were detected in tumors from 15 of the 49 patients. Of these patients, 13 responded to olaparib.

Previous prostate cancer genomic sequencing efforts had identified genetic aberrations, including mutations in DNA repair genes, which caused defects in the repair of DNA in these tumors. The researchers hypothesized that olaparib, which targets those tumor cells that are particularly vulnerable to DNA repair defects, may work in this subset of prostate cancer patients.

“It is known from previous trials that patients with prostate cancer and germline BRCA2 mutations respond to olaparib but they represent less than 2% of cases,” Mateo told Cancer Network. According to Mateo, prior sequencing studies showed that as many as one-fifth to one-third of prostate tumors developed somatic BRCA2 mutations. “Despite being different genes, many of [these genes] have shown, in preclinical studies, to…sensitize tumors to PARP inhibition,” said Mateo.

Next-generation sequencing identified homozygous deletion in BRCA2 and ATM, as well as biallelic loss of other genes implicated in DNA repair, including the Fanconi anemia complementation group and CHEK2. All seven patients with either germline or somatic BRCA2 loss and 4 of the 5 patients with ATM truncating mutations responded to olaparib.

“[This] means we can now better identify [patients who are] more likely to respond to olaparib. These results are not only important for prostate cancer but also can help to develop PARP inhibitors in other cancers,” said Mateo.

The specificity of the DNA repair gene panel was 94%, meaning that 94% of patients without these mutations can be correctly identified as having tumors with wild-type versions of these genes, according to Mateo. Patients who don’t have these mutations are not likely to benefit from olaparib.

The patients on this trial were enrolled at seven different UK centers and had previously been treated and progressed on one or two lines of chemotherapy. Patients received 400 mg of olaparib twice daily.

Consistent with previous olaparib studies in other tumor types, anemia and fatigue were the most common grade 3 or higher adverse events. Thirteen (26%) patients required a dose reduction.

The researchers are now testing this prostate cancer stratification strategy in a second part of the TOPARP trial, enrolling only those patients who have mutations in genes associated with DNA repair.

“We are now conducting a second validation trial that prospectively screens patients for mutations in these genes of interest, which just opened to recruitment in the United Kingdom earlier this month,” said Mateo. By the end of the year, the authors also expect to open a randomized phase II study of olaparib in earlier-stage prostate cancer patients.