Novel Imatinib/Nilotinib Strategy Could Optimize CML Treatment

A single-arm, open-label trial in Australia found that selective early switching from imatinib to nilotinib is feasible and effective in patients with CML.

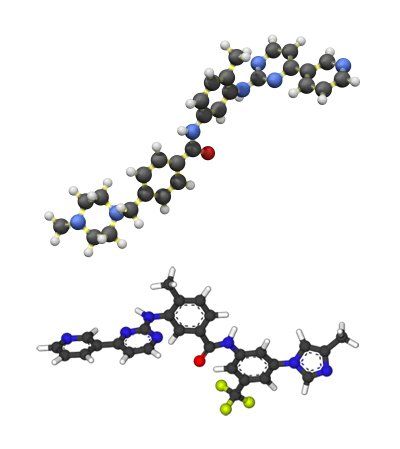

Ball-and-stick models of imatinib (top) and nilotinib (bottom)

A single-arm, open-label trial in Australia found that selective early switching from imatinib to nilotinib is feasible and effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

“The TIDEL-II study aimed to optimize treatment outcomes by maximizing the number of patients reaching [European Leukemia Net] treatment milestones,” wrote study authors led by Timothy P. Hughes, of SA Pathology in Adelaide, Australia. The study built upon TIDEL-I, in which imatinib treatment was intensified based upon early targets.

In the new TIDEL-II study, two sequential cohorts totaling 210 patients with CML were enrolled. All patients in both cohorts began treatment with imatinib 600 mg/day. At 22 days imatinib could be intensified to 800 mg/day if plasma trough levels were below 1,000 ng/ml.

BCR-ABL1 levels (targets included ≤ 10%, ≤ 1%, and ≤ 0.1%) at 3, 6, and 12 months were then used to determine treatment plan. In cohort 1, if patients failed any target they were escalated to imatinib 800 mg/day, and then switched to nilotinib 400 mg twice daily if the same target was failed 3 months later. In cohort 2, failing to hit a target resulted in immediate switching to nilotinib; intolerance or loss of response in either cohort also resulted in switching to nilotinib.

At 12 months, 10% of cohort 1 and 12% of cohort 2 had a confirmed complete molecular response. At 24 months, these rates were 22% and 28%.

A total of 78 patients failed to reach TIDEL-II targets, the authors reported. Fourteen of them remained on imatinib therapy (13 on 800 mg/day), and 12 achieved major molecular response (MMR) at 24 months; 10 withdrew from the study with no further intervention. A total of 54 patients switched to nilotinib after a median of 7 months; 39% of those (21 patients) were in MMR at 24 months. Another 19 patients switched from imatinib to nilotinib after imatinib toxicity (but without failing any targets), and another 5 patients switched after a loss of response to imatinib between 8 and 23 months.

At the 2-year mark, 55% of all the patients remained on imatinib, and 30% remained on nilotinib. Only 12% of the full cohort were > 10% BCR-ABL1 at 3 months. The overall survival rate in the trial was 96%, and transformation-free survival was 95% at 3 years.

“TIDEL-II represents a novel and effective treatment option for the management of treatment-naive [chronic phase]-CML patients,” the authors concluded. It balances the fact that while some patients may need a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) such as nilotinib, using those drugs as first-line therapy can lead to long-term toxicity. “The strategy allows selection of patients who are less sensitive to or are intolerant to imatinib, and switching them to nilotinib in a time-dependent manner to minimize treatment failure.” They added that as generic imatinib becomes available, this may become an even more attractive approach given the high cost of some second-generation TKIs.

Targeted Therapy First Strategy Reduces Need for Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed LBCL

December 7th 2025Lenalidomide, tafasitamab, rituximab, and acalabrutinib alone may allow 57% of patients with newly diagnosed LBCL to receive less than the standard number of chemotherapy cycles without compromising curative potential.