Personalized T-Cell Therapy for Brain Cancer

Researchers have shown that reprogramming T cells to target glioblastoma in mice resulted in control of these tumors.

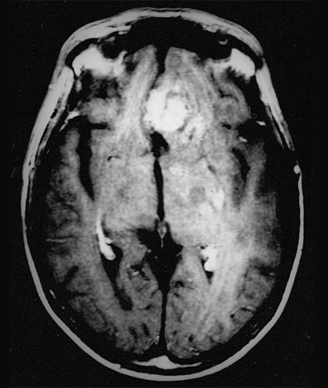

Recurrent glioblastoma multiforme

Researchers have shown that reprogramming T cells to target glioblastoma in mice resulted in control of these tumors. The approach, shown to be safe in mice, is now being tested in humans: A new glioblastoma clinical trial has just opened at the University of Pennsylvania to test this chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) immunotherapy.

The results of the animal study were published in Science Translational Medicine.

Marcela Maus, MD, PhD, of the division of hematology and oncology at the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center in Philadelphia, and colleagues designed murine T cells to express a CAR that targets the epidermal growth factor receptor protein, EGFRvIII. This protein is expressed on approximately 30% of glioblastomas.

CARs are engineered, synthetic molecules that are designed to be expressed on T cells extracted from a patient. T cells are extracted from a patient’s blood sample and modified in vitro. The CAR-modified T cells are then infused back into the patient to direct the T cells to attack the protein on the tumor. The researchers at the University of Pennsylvania had developed this immunotherapy technique and demonstrated its utility in treating patients, including children, with B-cell malignancies.

Glioblastomas are generally aggressive, rapidly growing tumors. Adults with this form of brain cancer generally have a median survival of about 15 months after diagnosis. Patients whose glioblastomas express EGFRvIII have an even more aggressive form of the disease, are less likely to respond to the standard therapies-usually chemotherapy and radiation therapy-and are more likely to recur post-treatment.

In the current study, the authors first demonstrated that the CAR-expressing T cells were able to specifically proliferate, secrete cytokines, and lyse in response to the EGFRvIII antigen. The specificity of the EGFR-targeting T cells was validated both in vitro, using EGFR-expressing keratinocytes, and in vivo, using a mouse model with grafted noncancerous human skin. The EGFRvIII-targeting T cells bound only to mutated EGFR and not wild-type EGFR found in noncancerous cells.

In mouse models, the CAR T cells could control the growth of tumors expressing human EGFRvIII, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging scans of the mouse brains. In some mice, the tumors disappeared entirely.

Based on these studies in mice, the study team has started a phase I pilot trial of EGFRvIII CAR T cells in patients with glioblastoma whose tumors are EGFRvIII-positive (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02209376). The trial plans to enroll 12 glioblastoma patients, 6 with recurrent disease and 6 with newly diagnosed disease who have 1 cm or more of tumor tissue remaining after surgery. The clinical trial is sponsored by Novartis, which has an agreement with the University of Pennsylvania to develop and commercialize the CAR T-cell immunotherapy approach.

This mouse study underscores the ability of this immunotherapy approach to potentially work for solid tumors. Using the CAR T-cell therapy approach has been met with hurdles in solid tumors, as many of the potential antigens expressed on solid tumors are also expressed on normal tissue. “A series of Penn trials that began in 2010 have found that engineered T cells have an effect in treating some blood cancers, but expanding this approach into solid tumors has posed challenges,” said Maus in a statement. “A challenging aspect of applying engineered T-cell technology is finding the best targets that are found on tumors but not normal tissues. This is the key to making this kind of T-cell therapy both effective and safe.”