Problem-Related Distress in Cancer Patients Drives Requests for Help: A Prospective Study

The Moores UCSD Cancer Center has implemented the use of an innovative instrument for screening cancer patients at first visit to assist them with distress due to cancer-related problems. This 36-question screening instrument addresses physical, practical, social, psychological and spiritual problems. Patients are asked to rate the severity of each problem on a scale of 1 to 5, and to circle "Yes" if they would like staff assistance. Data from a prospective study of the first 2,071 patients to complete this questionnaire has been entered into a database and analyzed to identify common patient problems, demographics, and trends. The five most common causes of problem-related distress were fatigue, sleeping, finances, pain, and controlling my fear and worry about the future. The five most common problems for which patients circled "Yes" to ask for assistance were understanding my treatment options, fatigue, sleeping, pain, and finances. Compared to the entire population, patients who circled "Yes" on a particular problem, demonstrated a robust increase in problem-related distress.

The Moores UCSD Cancer Center has implemented the use of an innovative instrument for screening cancer patients at first visit to assist them with distress due to cancer-related problems. This 36-question screening instrument addresses physical, practical, social, psychological and spiritual problems. Patients are asked to rate the severity of each problem on a scale of 1 to 5, and to circle "Yes" if they would like staff assistance. Data from a prospective study of the first 2,071 patients to complete this questionnaire has been entered into a database and analyzed to identify common patient problems, demographics, and trends. The five most common causes of problem-related distress were fatigue, sleeping, finances, pain, and controlling my fear and worry about the future. The five most common problems for which patients circled "Yes" to ask for assistance were understanding my treatment options, fatigue, sleeping, pain, and finances. Compared to the entire population, patients who circled "Yes" on a particular problem, demonstrated a robust increase in problem-related distress.

Not surprisingly, cancer patients experience unique life problems and high levels of distress throughout the diagnosis and treatment process, yet this phenomenon has been acknowledged only in the past 25 years.[1] The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends distress screening for cancer patients,[2] and the literature supports the use of distress screening to address problems before a crisis necessitates intervention.[3-5]

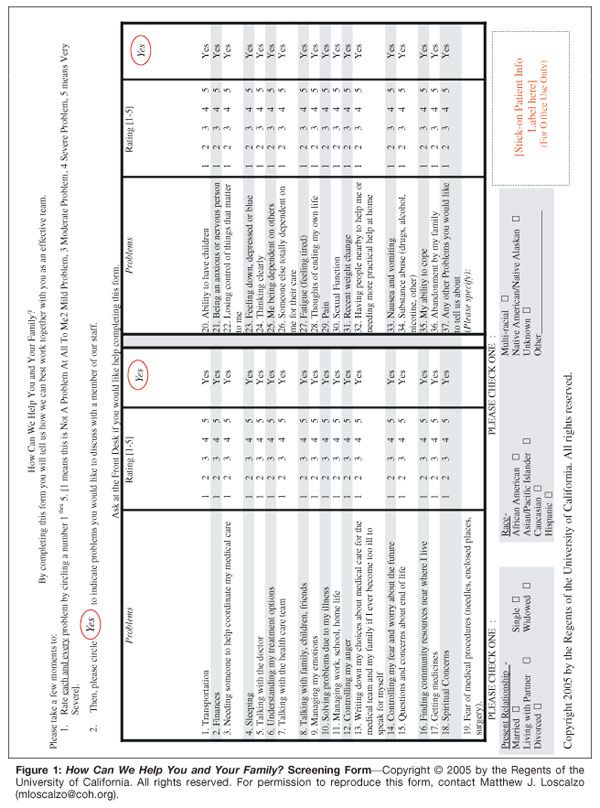

From the July 2005 opening of the Moores UCSD Cancer Center, a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, all patients have been screened for problem-based distress at first visit. Based on 10 years of experience in cancer problem–related distress screening,[6] we have developed a biopsychosocial screening instrument titled How Can We Help You and Your Family? (see Figure 1). For clinical purposes, individual screening data have been used to refer distressed patients for supportive care within the Science of Caring team. For research purposes, screening data have been entered into a database for analysis to identify common problems and trends. Using this information, we have developed and continue to modify our educational and intervention programs in a way that is tailored to the needs of our patient population.

Prospective Study

The UCSD Internal Review Board approved this prospective study for 4 years, with the addendum that the survey would be administered via touch-screen computer after January 2007. Patient informed consent was not required, as the data were used for clinical treatment, independently of the study. The 36-question paper version of the screening instrument was administered to 2,071 patients at their first visit to the Moores UCSD Cancer Center, between July 2005 and December 2006. The refusal rate was approximately 1%.

The questionnaire takes approximately 5 minutes to complete and includes demographic data on gender, date of birth, marital status, race, and primary language. For each question, patients were asked to rate the severity of the problem on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating it is "Not a Problem At All To Me" and 5 indicating it is the "Worst Problem I Could Have." A rating of 3 indicates a moderate level of distress with respect to the problem identified. To meet the needs of our patients, any problem rated ≥ 3 is triaged to a physician, nurse case manager, or social worker for assessment.

In addition, patients were asked to circle "Yes" if they would like to discuss this problem with a member of the staff. Any "Yes" response also results in an assessment. Assessment by a social worker might lead to actions ranging from a phone call suggesting a particular educational or support group, or a referral to a pain specialist, chaplain, or psychiatrist. All 36 questions of the How Can We Help You and Your Family? screening instrument are listed in Table 1 in descending order, based on the percentage of patients who rated that problem ≥ 3. Table 1 also shows the percentage of respondents who requested assistance for each problem by circling "Yes."

For each patient, we have created an overall problem-related distress score to further understand differences by demographic groups, stage, and diagnosis. The overall score represents the sum of all problems rated ≥ 3, yielding a score ranging from 0 to 36. Using this formula, a higher score indicates a greater number of individual problems reported ≥ 3. Our patient population for this study was 68.3% female, likely due to the prominent breast cancer program. However, there were no significant gender differences in the overall problem-related distress score.

Approximately 57% of our patients were married, and an additional 5% were living with a partner. Single patients showed a significantly greater overall problem-related distress score (mean = 6.97, standard deviation [SD] = 7.00) than married patients (mean = 4.88, SD = 5.69; P < .05). Ethnicity was typical for Southern California-70.4% Caucasian, 11.1% Hispanic, 7.6% Asian, 4.6% African-American, 6.2% other. Non-Caucasians (particularly the Hispanic population) showed significantly more problem-related distress. Hispanics rated 18 of the 36 problems ≥ 3 with a significantly higher frequency than Caucasians (P < .05), whereas Caucasians rated only one problem (understanding my treatment options) ≥ 3 significantly more often than Hispanics.

Of the 2,071 participants, cancer staging and diagnosis data from the tumor registry are available for only a subset of patients (505 and 671 patients, respectively). Of the 505 staged patients, 26.5% had stage I disease, 23.6% stage II, 20.1% stage III, and 21.8% stage IV-a relatively even distribution. The most prevalent diagnoses (n = 671), listed in descending order, are breast, hematologic, gastrointestinal, lung, and head/neck cancers. Lung cancer patients showed the highest overall levels of problem-related distress and "Yes" answers (although not significantly different from other groups), corresponding with findings by Zabora et al.[7]

Key Findings

Based on the percentage of people who marked ≥ 3 for a particular problem, the five most common causes of problem-related distress were fatigue, sleeping, finances, pain, and controlling my fear and worry about the future. The five most common problems for which patients circled "Yes" to ask for help were understanding my treatment options, fatigue, sleeping, pain, and finances. The ordinal ratings of the top five most prevalent problems in the "Yes" responses and problems rated ≥ 3 were the same, with the exception of understanding my treatment options, which is consistently the most common problem for which patients responded "Yes," they wanted to speak to a member of the staff.

Compared to the entire population, patients who circled "Yes" on a particular problem demonstrated a robust increase in problem-related distress. In Figure 2, the average problem-related distress scores for the top five problems rated ≥ 3 were plotted against the scores for the entire population, showing a difference ranging from 1.64 to 2.18 points (out of a possible 4). Scores for those who circled "Yes" compared to those who did not circle "Yes" on a particular problem demonstrated an even greater difference in problem-related distress, ranging from 1.74 to 2.36 (see Figure 2). Overall patients asking to speak with a member of the health-care team about a particular problem clearly manifested much higher levels of problem-related distress.

All patients who either ranked a problem ≥ 3 or circled "Yes" met the problem-related distress criteria for assessment, and this represented 77% of our patient population. This percentage is much higher than the more psychologically based screening instruments, for which distress "cutoffs" identify from 25.7% to 42.9% of the patient population as distressed.[4,7-9] The How Can We Help You and Your Family? screening instrument measures problems that people with cancer experience in their everyday lives and is not restricted to psychological issues. The current screening program is carefully integrated with medical care and practical assistance from first visit and represents the standard of care. Patients are therefore much more likely to identify problems, knowing that assistance is available.

Screening Innovations

Based on the literature in the field and combined staff experience, we have made several adaptations to our screening methodology, designing and modifying a screening instrument that best suited the needs of this population. Problem-related distress levels and patient desire for staff assistance are recorded for every problem on the screening instrument. This innovation has proven invaluable. For example, while understanding my treatment options was reported as the most frequent problem for which patients requested assistance, in the rankings of problems rated ≥ 3, it was only the ninth most common problem.

The patient's option to choose "Yes" in addition to rating problem-related distress levels seems to uncover problems that may be less common but more serious or urgent in nature. Another departure from other screening instruments is that questions concerning emotional, spiritual, practical, and physical concerns are purposely intermixed to give them equal validity in the eyes of the respondent. This change may help remove some of the stigma of "weakness" or "mental illness" from certain problems.

Program Evolution

The Science of Caring program is still in the development phase and the results from the first 18 months of this screening are essentially an enormous pilot study that has been used for design and implementation of tailored treatment options. For example, based on the significantly higher level of problem-related distress seen in the Hispanic population, a monthly support group called "Grupo Esperanza: A Culturally Sensitive Model of Group Support for a Spanish-Speaking Cancer Population" was created to address the specific psychosocial needs of Hispanics.

At the early stages of program development, follow-up was not always consistent or timely due to staff limitations. However, Velikova et al showed that the screening process itself offers some patient benefit even without intervention.[10] Using this study dataset as a concrete representation of patient needs enabled us to procure additional funding for support programs and staff. Currently, the screening program is linked to an integrated systematic triage process. As the Science of Caring program continues to evolve, the goal of caring for the whole person proactively, rather than merely reactively, is greatly enhanced.

Touch-Screen Version

Both in our own experience and in the literature,[8,11] a discrepancy exists between the detection of problem-related distress and referral for treatment. Use of a computerized touch-screen version of this paper screening instrument was initiated in January 2007 and should help us bridge this gap. The touch-screen version is in the process of being validated in comparison to other standard distress-screening instruments. Individual patient data from the touch-screen instrument is much more quickly and easily disseminated to the medical and support staff via e-mail and paper copy, enabling the provision of timely treatments. Periodic 2-month follow-up screening, as well as repeat screening at the initiation of new treatments such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and bone marrow transplant will allow us to follow patient progress and respond to changes in problem-related distress. In response to the needs of our Hispanic population, the touch-screen version is also offered in Spanish.

The screening instrument How Can We Help You and Your Family? was designed with the goal of anticipating and effectively responding to patient needs through direct interventions as well as through directed program modifications. In addition to a positive impact on patient health and well-being, there is a potential cost benefit to the cancer center if crises can be avoided and patient compliance improved [12].

-Matthew J. Loscalzo, MSW

-Karen L. Clark, MS

Disclosures:

The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

1. Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 249:751-757, 1983.

2. NCCN: Distress: Treatment Guidelines for Patients, ed II. National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Cancer Society, 2005.

3. Hoffman BM, Zevon MA, D'Arrigo MC, et al: Screening for distress in cancer patients: The NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psychooncology 13:792-799, 2004.

4. Sellick SM, Edwardson AD: Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychooncology 2006.

5. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen P, et al: A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics 42:241-246, 2001.

6. Zabora JR, Loscalzo MJ, Weber J: Managing complications in cancer: Identifying and responding to the patient's perspective. Semin Oncol Nurs 19:1-9, 2003.

7. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al: The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 10:19-28, 2001.

8. Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al: High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 90:2297-2304, 2004.

9. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al: Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer 103:1494-1502, 2005.

10. Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al: Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22:714-724, 2004.

11. Keller M, Sommerfeldt S, Fischer C, et al: Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: A multi-method approach. Ann Oncol 15:1243-1249, 2004.

12. Carlson LE, Bultz BD: Benefits of psychosocial oncology care: Improved quality of life and medical cost offset. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:8, 2003.

Oncology Peer Review On-The-Go: Cancer-Related Fatigue Outcome Measures in Integrative Oncology

September 20th 2022Authors Dori Beeler, PhD; Shelley Wang, MD, MPH; and Viraj A. Master, MD, PhD, spoke with CancerNetwork® about a review article on cancer-related fatigue published in the journal ONCOLOGY®.

Late Hepatic Recurrence From Granulosa Cell Tumor: A Case Report

Granulosa cell tumors exhibit late recurrence and rare hepatic metastasis, emphasizing the need for lifelong surveillance in affected patients.

Oncology Peer Review On-The-Go: Cancer-Related Fatigue Outcome Measures in Integrative Oncology

September 20th 2022Authors Dori Beeler, PhD; Shelley Wang, MD, MPH; and Viraj A. Master, MD, PhD, spoke with CancerNetwork® about a review article on cancer-related fatigue published in the journal ONCOLOGY®.

Late Hepatic Recurrence From Granulosa Cell Tumor: A Case Report

Granulosa cell tumors exhibit late recurrence and rare hepatic metastasis, emphasizing the need for lifelong surveillance in affected patients.

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.