Protein in Prostate Biopsy May Signal Higher Risk of Cancer

A new study shows that men who have a specific protein marker present in their prostate biopsy may benefit from close follow-up and additional biopsies as they may be at increased risk of developing cancer.

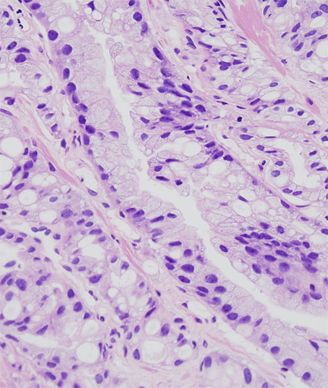

Histopathologic image of prostate obtained by core needle biopsy; source: KGH, Wikimedia Commons

A new study shows that men who have a specific marker present in their prostate biopsy may benefit from close follow-up and additional biopsies. When present, the marker-a protein found in the biopsied tissue-increases the chance that cancer will develop in the prostate. This could identify patients that need to be carefully monitored from those that do not, a decision that is currently difficult to make for clinicians. The study is published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Generally, men with detectable high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) have a higher risk of developing prostate cancer. About 40% of these men are diagnosed with prostate cancer within 3 years of HGPIN detection and 80% are diagnosed within 8 years. Patients with HGPIN are recommended to receive follow-up biopsies every 3 to 6 months as well as regular prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing. However, care of these patients varies by clinician. A biomarker that can better predict which men need vigilant follow-up because of a significant risk of developing prostate cancer in the short term would help to stratify patients to receive the appropriate level of care and testing.

Mark Rubin, MD, professor of oncology and pathology at the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, and colleagues retrospectively evaluated tumor biopsy samples from 461 men who took part in the GTx Protocol G300104, a phase III treatment trial that took patient biopsies at baseline, and every year for 3 years during follow-up.

The goal was to understand whether the expression of a gene fusion called ERG in the tumor tissue correlated with higher risk of developing prostate cancer. Previous studies have shown that about half of prostate cancers overexpress the ERG fusion which links the promoter of the androgen-regulated transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) gene to the coding region of the v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (ERG). The presence of this gene fusion is present in prostate tumors and HGPIN but not in benign hyperplasia and studies suggest that this fusion may be an early event in prostate cancer, at least for a proportion of cases.

The study is the largest conducted that focuses on looking at HGPIN and ERG, according to the study authors. “We found that more than half of patients with these biomarkers go on to develop prostate cancer, and that is a significant finding which we now want to test in a prospective clinical trial,” said Rubin in a statement.

Rubin and colleagues used immunohistochemistry to detect the presence of ERG protein expression. They were able to detect ERG expression in 11.1% of patients (51 of 461 patients) who had confirmed HGPIN. During the first year, 14.7% of patients were diagnosed with prostate cancer and 36.9% were diagnosed within the 3-year trial follow-up. Patients with positive ERG expression (53%; 27 of 51) were more likely to develop prostate cancer compared with patients who were ERG negative (35%; 143 of 410; P = .014).

Because the assay depends on the level of ERG expression present in tissue, the researchers previously developed a threshold expression level that is highly reproducible, Rubin told Cancer Network. “We are confident that this test can be used by pathologists,” said Rubin.

“This study underscores the necessity of more stringent follow-up for men with HGPIN that is also positive for ERG overexpression,” the authors concluded. “Clinicians should consider molecular characterization of HGPIN as a means to improve risk stratification.”

The immunohistochemistry diagnostic is available through Roche and prospective clinical studies for further validation are currently being planned.

Further testing in a larger patient cohort will show whether this assay could be used to stratify patients into higher and lower risk categories, allowing those who are lower risk to avoid further invasive biopsies and unnecessary frequent follow-up tests.

“We anticipate that molecular testing will become integrated into prostate cancer diagnosis,” Rubin said. “As we show in the current study, molecular classification can also help predict the risk of having cancer.”