ASCO GI: Improved GIST Survival With Residual Tumor Removal Post-Maintenance Imatinib

Assigning patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) to undergo surgical resection of residual tumor after disease control with maintenance imatinib was beneficial to patient survival, according to the results of a retrospective study presented at the ASCO 2013 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

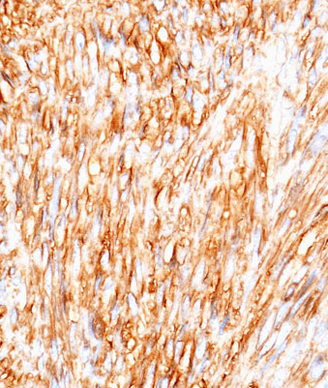

Histopathologic image of GIST arising in the stomach; CD34 immunostain

Assigning patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) to undergo surgical resection of residual tumor after disease control with maintenance imatinib was beneficial to patient survival, according to the results of a retrospective study presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2013 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

“Although imatinib shows great response initially in patients with metastatic or recurrent GIST, secondary resistance eventually develops in most of the patients,” Seong Joon Park, MD, a fellow in the department of oncology and surgery at Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, said during a press conference. “This study strongly suggests that surgical resection of the residual lesions after disease control with imatinib may be beneficial in patients with metastatic or recurrent GISTs.”

In this study, Park and colleagues sought to determine if the addition of surgery after maintenance treatment with imatinib would be of benefit to patients with metastatic or recurrent GIST compared with outcomes seen in patients given maintenance imatinib alone.

Researchers included 134 patients in the study, all of whom had shown clinical response to imatinib for at least 6 months. The study looked at patients who had either undergone surgical intervention (n = 42) after maintenance imatinib or those who were treated with imatinib alone (n = 92).

Median follow-up of the patients was 58.9 months. Surgery was performed in the surgical group at a median of 19.1 months of treatment with imatinib. At follow-up, surgical patients had significantly longer progression-free survival (87.7 months vs 42.8 months; P = .001) and overall survival (not reached vs 88.8 months; P = .001) compared with patients who were treated with imatinib alone.

To reduce the effect of selection bias in the retrospective, observational study, the researchers used several statistical analyses including univariate and multivariate analyses, propensity scores and inverse-probability weighting analysis.

In the multivariate analysis, results showed that for progression-free survival mutation type, initial tumor size and treatment group was associated with an increased survival. For overall survival, initial tumor size and treatment group was associated with better survival.

“Even after propensity score and inverse-probability weighting analyses were applied the surgical group still showed significantly better clinical outcomes,” Park said.

Park also emphasized that these results are the first to fully address the role of surgery in the treatment of GIST patients.

“Previous studies did not have a control group, but compared the clinical outcomes of only the patients who had received surgery,” Park said. “This treatment strategy is worth trying as a clinical practice, if the medical center is large enough to have [an] experienced multidisciplinary team and to have low morbidity and mortality associated with surgery.”

When commenting about the study, Neal J. Meropol, MD, professor and chief of the division of hematology and oncology at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, noted that although GISTs are an uncommon type of gastrointestinal tumor, they have been a triumph of molecularly targeted therapy with imatinib, with imatinib providing disease controls for years in many patients.

“Unfortunately resistance ultimately develops to imatinib, so this study provides provocative evidence that taking an aggressive approach with surgical treatment, in addition to medical treatment with imatinib, may result in an even longer survival in patients with GIST,” Meropol said.