Childhood cancer haunts survivors in unexpected ways

Radiation doses to the heart of about 5 Gy or greater in childhood are associated with long-term cardiovascular consequences, including early mortality. Cancer care specialists strive to balance late-stage effects without sacrificing treatment benefits.

Radiation therapy can buy years or decades of life for children with various forms of cancer. But disease control or cure often comes at a very high price, in the form of late-term cardiotoxicities and significantly increased risk for early death.

A new study of nearly 18,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the UK showed that cause-specific standardized mortality ratios were 11 times higher than expected based on general population data and that most of the deaths were attributable to second primary cancers and to cardiac, cerebrovascular, and other circulatory disorders. (JAMA 304:172-179, 2010).

A separate study looking at more than 86,000 person-years of follow-up among 4,122 survivors of childhood cancers treated in France and the UK before 1986 reported that those who had received at least 5 Gy of cumulative radiation to the heart had a 12-fold higher risk for cardiovascular death compared with the general population of those countries, and those who received more than 15 Gy had a 25-fold higher risk. (J Clin Oncol 28:1308-1315, 2010).

"This is a very serious problem, and it is primarily due to radiation therapy of young people with hematologic cancers, like Hodgkin's lymphoma. Heavy radiation is given to the chest area, and 10 to 20 years later the patients develop all kinds of very serious cardiac problems and associated difficulties, any one of which can cause death," said Barrie R. Cassileth, PhD, who holds the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and is chief of the integrative medicine service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Oncology News International spoke with physicians who follow survivors of childhood malignancies. They discussed the types of toxicities they see, how they manage these late-term effects, and how to engage patients in their own long-term care.

One-two punch

Many young cancer patients get a double whammy to the heart, receiving a combination of radiation to the chest and chemotherapy with anthracyclines, which are associated with cardotoxicities at higher lifetime cumulative doses, noted Daniel Mulrooney, MD, an assistant professor in the division of pediatric hematology/oncology/blood and marrow transplantation in the pediatrics department at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

"Anthracyclines tend to put a patient at higher risk for cardiomyopathy or congestive heart failure. That risk can be compounded by radiation therapy. Radiation therapy alone tends to increase the risk for coronary artery disease, valvular disease, pericarditis and similar issues that we don't see with anthracycline exposure alone," said Dr. Mulrooney, who is also director of the Long-Term Follow-Up Clinic for childhood cancer survivors at the university.

The mechanisms of the drug-induced and radiation-induced pathogenesis differ somewhat, but the mechanisms have not yet been fully elucidated. Anthracyline exposure induces direct oxidative damage in muscle cells, which can over time lead to congestive heart failure. Ionizing radiation also causes damage in a dose- and fractiondependent way but can result in narrowing and fibrosis of the arteries, which leads to earlier coronary artery disease. This can lead to fibrosis of the heart muscle and valvular tissues and vessels and cause a myriad of late effects including valvular stenoses or regurgitation, myopathies, a constrictive pericarditis, or conduction abnormalities, explained Torunn Yock, MD, director of pediatric radiation oncology and chair of quality assurance and improvement in the department of radiation oncology at Boston's Massachusetts General Hospital.

"When we used to treat Hodgkin's disease with radiation alone, we would have to bring the dose to about 40 Gy, which certainly causes late effects in the heart, such as increased incidence of coronary artery disease-it dramatically increases your risk for early cardiovascular disease," she said.

Most commonly seen late effects

Dr. Mulrooney, who is also an investigator in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, said that late-term radiation-induced cardiotoxicities are most commonly seen among adults who had been treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma as children.

"In the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, we looked across the board by diagnosis, and just looking at myocardial infarction or ischemic disease, we saw it in survivors of Hodgkin's, brain tumors, leukemia, neuroblastoma, sarcoma, and bone cancer. In fact, the only ones in whom we did not find it in our study were survivors of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas and kidney tumors, and it may be that the number of documented events in kidney tumors was just too small," he said.

Childhood cancer survivors may face 'exorbitant' insurance premiums

One emphasis of healthcare reform has been to provide uninsured children and adults with coverage. But childhood cancer survivors may be one group that is in danger of losing coverage, according to an editorial by Steven E. Lipshultz, MD, and M. Jacob Adams, MD.

"Childhood cancer survivors are a vulnerable group who are at risk for being charged exorbitant premiums and rejected for preexisting conditions, or who, after paying out for years, find their policies rescinded when they become sick," they wrote (J Clin Oncol 28:1276-1281, 2010).

Dr. Lipshultz is from the pediatrics department at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Holtz Children's Hospital. Dr. Jacobs is from the department of community and preventive medicine at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in New York.

"Going without insurance is an ominous harbinger for survivors because it inhibits access to the healthcare system and introduces barriers to needed care," they said. "Cancer survivors are 37% more likely to be unemployed than other people."

Late cardiotoxic effects of radiation have also been reported previously among older survivors of Wilms tumor who received whole lung or left-sided radiation, Dr. Mulrooney added.

"A common tumor that we see is medullablastoma, which requires treatment of the whole brain and the spine," Dr. Yock noted. "We know that patients treated with what used to be a standard dose, which is 36 Gy, get at least 50% of the dose exiting the body, so 50% to 80% of that dose is going to the heart, and that has caused a doubling of risk for cardiac problems."

Kill the tumor, protect the heart

With current radiotherapy techniques and better understanding of the pathogenesis of radiation-induced cardiotoxicity, oncologists are making significant strides in reducing the risk of future complications for today's pediatric cancer patients, said Louis S. Constine, MD, a professor of radiation oncology and pediatrics at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

"In Hodgkin's lymphoma we are constantly refining the role for radiation: the amount of radiation that needs to be given, and the volume of radiation that needs to be given. We're learning that in some situations in which we might previously have given radiation, it may not be critical that those patients receive radiation at all," said Dr. Constine, who is also vice chair of the department of radiation oncology at Rochester's James P. Wilmot Cancer Center.

Radiation doses and fields have also been steadily shrinking over the last several decades, he said. "For example, many years ago we treated regions of the body; in the last 15 years or so we moved to involved fields. Where we once treated all lymph nodes that were adjacent to those involved with lymphoma, now we're moving into an era when we simply treat areas of specific involvement. By restricting the radiation field to areas that are overtly or grossly involved by lymphoma, rather than [including] adjacent areas that might have subclinical, covert, or microscopic disease, we can treat much smaller areas of the body," Dr. Constine said.

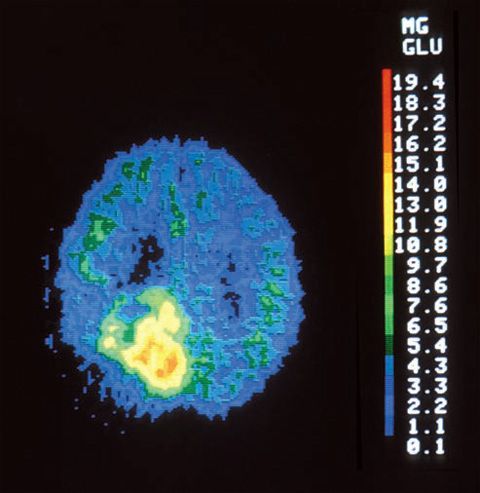

Advances in imaging with PET scanning have also made it possible to titrate radiation doses and target involved tissues more precisely, he added. "By using functional imaging, we can better determine those areas of the body that truly are at risk for Hodgkin's lymphoma and restrict the radiation initially to those FDG-PET-avid areas." Another means of protecting the heart, albeit a costly one with limited availability, is with protonbeam therapy rather than conventional photon radiation. There are currently seven proton therapy centers in operation in the U.S., four more under construction, and two in the development stage.

Dr. Yock, who works at one such center, said that proton-beam radiation therapy is increasingly being used to treat children and adults with Hodgkin's disease and large anterior mediastinal masses. One of the advantages of protons is that their energy level drops off precipitously just beyond the point of maximal energy delivery, meaning that tissues beyond the target get a smaller radiation dose than they would if treated with photons.

Caring for long-term survivors

The recent childhood cancer survivor studies showed that survivors remain at excess risk for cardiovascular morbidities and for death many decades after they have completed therapy. But adult survivors are often unaware of the risks, said Pamela Gabris, RN, coordinator for the Beyond the Cure survivorship program of the National Children's Cancer Society.

The NCCS has a free secure web-based late-effects assessment tool that allows patients and clinicians to enter data about the patient's cancer history, including gender, year of and age at diagnosis, treatments received, radiation sites, and surgery (see Fact box below). Based on the data entered, the program lists potential late effects the individual patient may experience, provides recommendations for follow-up care, offers prevention tips, and suggests links to follow- up clinics throughout the U.S. as well as other sources of information.

FACT

Late-effects assessment tool

Access lea.beyondthecure.org/ Unregistered.aspx? ReturnUrl=%2fDefault.aspx at the National Children's Cancer Society website.

"It's an easy tool to navigate, and it gives patients a good starting point to open up a conversation with their doctor. If they haven't been followed closely beyond treatment- and maybe they're not being seen in a long-term follow-up clinic, just in primary care-they can key in information there, too, to take to their primary care doctor and say 'At age five I was treated for leukemia. I pulled this assessment up, and these are some of the concerns. I've been having chest pain or fatigue,'" Ms. Gabris said.

The Children's Oncology Group periodically updates extensive guidelines (www.survivorshipguidlines.org) for follow-up of childhood cancer survivors. In the section on radiation, for example, the evidence-based guidelines recommend echocardiogram intervals based on the patient's age at radiation therapy and dose received.

The guidelines also report potential late effects, risk factors, and at-risk populations and recommend specific follow-up goals (see Fact boxes above and below).

FACT

NCI summary of late effects

Visit www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/ lateeffects/HealthProfessional to access the "PDQ Summary: Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer."

Despite the late-term risks of radiation, no one would dispute the essential role this treatment modality plays in pediatric oncology.

"We have to remember that the most important thing is to treat the primary disease and prevent recurrence. There is a role for radiotherapy, and we have to weigh the risks and the benefits of it," Dr. Mulrooney said.

"I'm concerned about late effect, but I think we really have to be careful that we adequately treat the first disease," Dr. Mulrooney emphasized.

Dr. Cassileth serves on the Oncology News International editorial advisory board.

© Scott Camazine/PhototakeUSA.com

FDG-PET scan of the brain showing a malignant tumor; area in red indicates glucose uptake. Childhood survivors of brain tumors who undergo radiation therapy often experience late-term cardiotoxicity, according to the results of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.