Commentary (Niederhuber): Pancreatic Cancer in the Older Patient

Pancreatic cancer is a disease seen predominantly in elderly patients. Compared to younger patients, older patients are more likely to present with early-stage disease and, therefore, may be candidates for aggressive local

Drs. Jacobson, Alberts, and O’Connell of the Mayo Clinic have provided a thoughtful review of the critical issues involved in managing elderly patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. In their introduction, they cite the existing evidence supporting the conclusion that, on the basis of age alone, elderly patients do not receive appropriate treatment. The authors’ review of the treatment of pancreatic cancer in the elderly provides several useful guidelines for managing this special group of patients and raises important questions for which we lack sound answers. As they emphasize, we have long struggled with the fact that patients in the eighth and ninth decades of life are poorly represented in clinical trials. The authors note that few studies have been conducted on how aging affects the pathogenesis of the developing tumor or how it affects the elderly patient’s host response to tumor progression.

While we lack data generated by clinical trials as well as important knowledge concerning the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer in this age group, those of us who provide care to a significant population of patients with such tumors have accumulated considerable personal experience. In the case of major malignancies of the hepatobiliary system and the pancreas, there is strong evidence that a successful outcome is almost exclusively dependent on whether or not the patient is referred to and managed by a high-volume regional medical center-especially one with a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Perhaps a few comments will add to this excellent review.

Managing Surgery

Based on reports from three statewide databases-Maryland, New York, and California-it has been well established that high-volume regional medical centers achieve superior outcomes at a lower cost when managing patients with pancreatic cancer.[1,2] The best report regarding outcomes for patients 80 years of age and older comes from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (the high-volume provider in the Maryland database).[3] Such older patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy had a slightly longer hospital stay (15 vs 13 days, P = .01) and a higher complication rate (57% vs 41%, P = .05) than did younger patients. The perioperative mortality rate for the over-80 age group was an acceptable 4.3% but higher than the 1.6% in the younger group. Even more important is the 19% 5-year survival rate, which is not significantly different from the rate for younger patients.

The conclusion to be drawn from the analysis of these statewide databases is that optimal care for those age 80 years and older with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is best accomplished in a high-volume center. The solution, however, is more complicated. Individuals in this age group often lack a spousal advocate or a strong family support system, and their ability to receive care at a high-volume provider is dependent on such advocacy. Travel is more difficult and almost always hinges on assistance from others.

These patients are generally on fixed incomes and find the issues of health-care insurance and access to plan-approved care overwhelming. Not only do they require a strong supportive family, but they also need the understanding and compliance of their primary health-care provider. Experienced practitioners who specialize in geriatric medicine do a great job of providing this support. With the appropriate referral, we can expect the same outcomes for this older age group as seen in younger patients.

Surgical Candidates and Postsurgical Care

Patients with symptoms for which the differential diagnosis includes cancer of the hepatobiliary system and pancreas are often initially evaluated by a gastroenterologist. It is important to obtain optimal computed tomography scans using dynamic technology, with and without contrast and thin slices, before performing instrumentation of the pancreatic or biliary tree and before placing a stent in the bile duct. This ensures an optimal image assessment of the head of the pancreas uncompromised by the endoscopic manipulation of the ductal system.

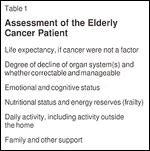

TABLE 1

Assessment of the Elderly Cancer Patient

The most important decision concerns careful selection of patients for surgery. While advanced age alone should never be an accepted reason for withholding effective treatment, the process of aging is associated with a progressive reduction in the functional reserve of various organ systems. The goals are prolongation of survival, maintaining quality of life, and palliation of symptoms. Thus, the key is careful assessment of organ systems, assessment of response to treatment of comorbid conditions, and a balancing of the risks vs the benefits of surgery (Table 1).

The management of patients in their 70s and 80s requires intense attention to detail in the operating room and during the recovery process. Careful handling of tissues and the avoidance of excessive blood loss and infection are critical to successful outcomes. I recall a professor of surgery who was fond of citing the surgical axiom, "old folks and babies have little tolerance for complications." I routinely plan for postsurgery nutritional supplementation for this group of older patients using a temporary jejunostomy feeding tube. These patients also benefit from the early initiation of physical therapy.

After surgery, the next question concerns adjuvant chemoradiation. It is important to make every effort to implement this aspect of the treatment plan. Instead of beginning 4 to 6 weeks following surgery, adjuvant therapy is sometimes initiated closer to 6 weeks postsurgery so as to allow a little more time for recovery.

When There Is Advanced Unresectable Tumor

As when evaluating patients with resectable tumors, patients whose disease is clearly unresectable need to be carefully assessed for functional reserve of their organ systems and their ability to manage palliative chemoradiation. Radiation oncologists are sometimes reluctant to treat the primary tumor and regional nodes if the patient has liver or lung metastases. I, however, have had the benefit of working with an excellent team, and our experience has confirmed that elderly patients achieve better outcomes with protracted infusional fluorouracil (5-FU) than with bolus chemotherapy. They develop less hematologic toxicity and tolerate radiation quite well. Radiation in combination with 5-FU produced the best palliation of symptoms, decreased the incidence of outlet obstruction as a late-stage complicating factor, improved pain control, and provided the majority of patients with an 18- to 24-month good-quality survival.

References:

1. Yeo CJ: Pancreatic surgery, in Gordon TA, Cameron JL (eds):Evidence-Based Surgery, pp 331-356. Hamilton, Ontario, BC Decker Inc, 2000.

2. Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Gordon A, et al: Importance of hospitalvolume in the overall management of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 228:429-438,1998.

3. John TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al: Shouldpancreaticoduodenectomy be performed in octogenarians? J Gastrointest Surg2:207-216, 1998.