Current Management of Unusual Genitourinary Cancers: Part II

Often overshadowed by more common genitourinary cancers, such as prostate, testicular, and kidney cancers, penile and urethral cancers nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges for the clinician. The management of these cancers is slowly evolving. In the past, surgery, often extensive, was the treatment of choice. Recently, however, radiation and chemotherapy have begun to play larger roles as initial therapies, with surgery being reserved for salvage. With these modalities in their treatment armamentarium, oncologists may now be able to spare patients some of the physical and psychological sequelae that often follow surgical intervention without compromising local control and survival. Part 1 of this two-part article, published in last month’s issue, dealt with cancer of the penis. This second part focuses on cancer of the urethra in both females and males. [ONCOLOGY 13(11):1511-1520, 1999]

ABSTRACT: Often overshadowed by more common genitourinary cancers, such as prostate, testicular, and kidney cancers, penile and urethral cancers nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges for the clinician. The management of these cancers is slowly evolving. In the past, surgery, often extensive, was the treatment of choice. Recently, however, radiation and chemotherapy have begun to play larger roles as initial therapies, with surgery being reserved for salvage. With these modalities in their treatment armamentarium, oncologists may now be able to spare patients some of the physical and psychological sequelae that often follow surgical intervention without compromising local control and survival. Part 1 of this two-part article, published in last month’s issue, dealt with cancer of the penis. This second part focuses on cancer of the urethra in both females and males. [ONCOLOGY 13(11):1511-1520, 1999]

Introduction

FIGURE 1

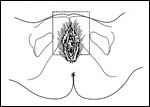

Anatomy of the Female UrethraFIGURE 2

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Female UrethraFIGURE 3

Magnetic Resonance Scan (MRI) of a Female Urethral Carinoma

Penile and urethral cancers, while less common than other genitourinary cancers such as prostate, testicular and kidney carcinomas, nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges. The management of these cancers is slowly evolving as radiation therapy and chemotherapy begin to play larger roles in treatment. Part 1 of this two-part article, published in last month’s issue, dealt with cancer of the penis. This second part focuses on cancer of the urethra in both females and males.

Cancer of the Female Urethra

Epidemiology and Etiology

Carcinoma of the female urethra is a rare tumor, accounting for fewer than 1% of all cancers in the female genitourinary tract.[1] It is most commonly seen during the fifth and sixth decades of life. Only about 1,000 cases have been reported in the literature.[1]

Urethral cancer shows a predilection for women over men (4:1 ratio). The incidence of this cancer is higher in white than in black women.[2]

The human papilloma virus may play a role in the development of urethral cancer in women.[3]

Anatomy

In females, the urethra (Figure 1) is approximately 4 cm long (range, 2 to 6 cm),[2,4] and most of it is buried in the anterior vaginal wall.[2] The urethra is divided into the distal one-third (anterior urethra) and the proximal two-thirds (posterior urethra).

Pathology

The majority (70%) of neoplasms of the female urethra are squamous cell carcinomas (Figure 2). Other less common histologies that have been reported include transitional cell carcinoma (15%), adenocarcinoma (13%), and undifferentiated carcinoma (2%).[1]

Routes of Spread

The lymphatics from the proximal urethra drain primarily into the pelvic nodes (external iliac, obturator, and presacral),[4,5] whereas those of the distal urethra drain primarily into the inguinal nodes.[4] Unlike the situation in patients with penile carcinoma, palpable inguinal nodes in patients with urethral cancer usually contain metastatic carcinoma.[1] Approximately 14% to 30% of patients with urethral carcinoma have inguinal lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis.[4]

The most common sites of distant spread are the lungs, liver, and bone.[1]

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic and Staging Work-up

TABLE 1

TNM Staging of Urethral Cancer

The most common presenting symptom is urethral bleeding,[1] seen in 56% of cases. Other symptoms include urinary obstructive symptoms, urinary frequency, perineal pain, palpable mass, and urinary incontinence.

The work-up for women with suspected urethral carcinoma includes cystourethroscopy, an excretory urogram, computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis and abdomen, chest x-ray, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis (Figure 3).

Staging

The TNM staging system for carcinoma of the urethra (in both females and males) is shown in Table 1.

Treatment

Surgery-Various surgical techniques that maintain continence have been used to treat early carcinomas involving the distal urethra. Procedures range from laser excision to local excision, transurethral excision, and partial urethrectomy.[2] Bladder-sparing procedures have been performed successfully in selected patients with T3 lesions.[6]

Patients with advanced disease of the entire urethra extending to bladder and vagina may be treated surgically with anterior exenteration. This involves removal of the pelvic lymph nodes, entire urethra, and uterus with appendages, along with en bloc resection of the pubic symphysis and inferior rami (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Anterior exenteration alone, however, has been reported to produce a 5-year survival rate of less than 20% in patients with invasive carcinoma,[2] with a significant incidence of local failure (> 66%).[2,7]

FIGURE 4

Anterior Pelvic ExenterationFIGURE 5

Anterior Pelvic Exenteration

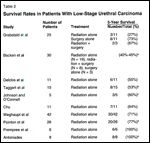

Radiation therapy is an alternative to local surgery for patients with low-stage urethral carcinoma.[8-13] In such patients, definitive radiation therapy produces cure rates averaging about 75% (Table 2).[8,13,14] In general, patients treated with radiation have received brachytherapy either alone or combined with external-beam radiation therapy. The doses in the various series range from 5,000 to 6,000 cGy for brachytherapy alone to 4,000 to 4,500 cGy of external radiation to the whole pelvis followed by a brachytherapy boost of 2,000 to 2,500 cGy over 2 to 3 days. As most of these lesions are distal in location, the inguinal nodes are at risk. Thus, if whole-pelvis radiation is delivered, care must be taken to include the inguinal nodes, as well as the iliac, obturator, and presacral nodes. The pelvis, groins, and primary lesion receive 4,500 cGy in 25 fractions. External-beam therapy is followed by a brachytherapy boost, for a total tumor dose of 6,500 to 7,000 cGy.[14,15]

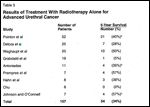

In patients with advanced urethral cancer, radiation therapy alone offers 5-year survival rates ranging from 5% to 57% and averaging approximately 34% (Table 3).[2] The studies in this table represent a heterogeneous group of patients with varying stages of diseases and radiation approaches. Patients with lesions involving the bladder neck probably should be excluded from this group because of the higher incidence of local failure after definitive radiation therapy.[12]

TABLE 2

Survival Rates in Patients With Low-Stage Urethral Carcinoma

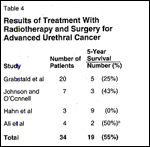

Surgery Plus Radiation Therapy-In the past, because of the overall poor results with either radiation or surgery alone in advanced carcinoma of the urethra, some authors recommended a combined-modality treatment approach involving preoperative radiation and surgery.[1,2,7,16] Various radiation schedules were used preoperatively, ranging from 2,000 cGy in 5 fractions[1] to 4,500 to 5,000 cGy in 25 fractions.[10,14]

In the relatively small numbers of patients treated, the combination of radiation and surgery may have offered some improvement over radiation alone for advanced lesions (Table 4). However, with the advent of fluorouracilmitomycin (Mitomycin)-radiation combinations (see “Chemotherapy” below), surgery may change from being an upfront therapy to a salvage modality for patients with advanced squamous cell urethral carcinomas.

Complications-The rate of complications of radiation therapy in females with cancer of the urethra has been reported to range from 0% to 42% (mean, approximately 20%).[14] Urethral strictures and stenosis are the most commonly reported complications. Urethrovaginal fistulas, incontinence, and necrosis have also been reported, depending on the size of the tumor, the total dose of radiation, and whether or not surgery is combined with radiation.

Chemotherapy

TABLE 3

Results of Treatment With Radiotherapy Alone for Advanced Urethral Cancer

In 1988, Sailer, Shipley, and Wang[14] described the effective use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in two patients with advanced transitional cell tumors. These patients received two cycles of methotrexate, a platinum agent, and vinblastine prior to radiation therapy and the platinum every 3 weeks during radiation (60 to 65 Gy). The treatment was satisfactorily tolerated.

Chemoradiation-More recently, a number of case reports have appeared in the literature documenting dramatic results with fluorouracil, mitomycin, and external-beam radiation[17-21] in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the urethra.

Johnson et al[20] reported a dramatic response to fluorouracil, mitomycin, and low-dose radiation (40 Gy) in a patient with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra, in which the initial 2.5 × 6 cm lesion shrunk to a thin 2-cm plaque. When the patient underwent a subsequent anterior exenteration, no evidence of gross disease was seen and according to pathologic analysis, only a 3 × 2 × 15 mm area of fibrous stroma with scattered nests of squamous cell carcinoma was seen.

Kalra et al[17] treated 15 patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the female genital tract, including 1 patient with urethral cancer, with fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiation. The patient with urethral cancer was reported to be free of disease at 36+ months of follow-up..

TABLE 4

Results of Treatment With Radiotherapy and Surgery for Advanced Urethral Cancer

Tran and Krieg[21] described the case of a patient with a 6 × 6 cm squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra presenting with a urethrovaginal fistula. The only surgery done was biopsy and urinary diversion. The patient received fluorouracil and mitomycin along with 5,580 cGy of external-beam radiation. She is now disease free for over 5 years with recent negative biopsies.

Similarly, Licht et al[18] et al reported on 2 female patients treated with fluorouracil-mitomycin and modest doses of external-beam radiation (5,000 and 4,320 cGy, respectively). Both patients have been free of disease for more than 94 months.

Thus, the combination of fluorouracil and mitomycin (as in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus) and external-beam radiation, with surgery reserved for salvage, appears to offer a very promising alternative to upfront radical surgery for women with squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra. Further investigation of this approach is clearly warranted.

Cancer of the Male Urethra

Etiology and Epidemiology

Carcinoma of the urethra accounts for fewer than 1% of malignancies in males; less than 600 cases of cancer of the male urethra have been reported in the world literature.[15] As mentioned previously, urethral cancer is four times less common in males than in females. Urethral tumors are diagnosed in most male patients when they are over 50 years of age.

Although the precise etiologic features of cancer of the male urethra have not been identified, there is a predisposition to this malignancy in patients with long-standing urethral infection.[15] Many patients have a history of venereal disease, stricture, trauma, or urethritis. A significant percentage of patients give a history of occupational exposure to known carcinogens or cigarette smoking.[15]

Anatomy

FIGURE 6

Anatomy of the Male Urethra

The male urethra extends from the neck of the bladder to the external urethral meatus and averages 21 cm in length.[22] The male urethra can be divided into anterior (distal) and posterior (proximal) portions (Figure 6). The anterior urethra is subdivided into the glanular, penile, and bulbous portions. The posterior urethra is subdivided into the membranous and prostatic portions.

Approximately 50% to 75% of urethral neoplasms originate in the bulbar urethra. Bulbar lesions are usually included clinically as belonging to the posterior urethra, although anatomically, they are part of the anterior urethra.

Pathology

FIGURE 7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Male Urethra

Squamous cell carcinomas account for 78% of carcinomas of the male urethra (Figure 7). The transitional epithelium of the prostatic urethra gives rise to transitional cell carcinoma in approximately 15% of cases.[22] Rarely, adenocarcinoma is found in the bulbar urethra.

Routes of Spread

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anterior urethra can rapidly invade the corpus cavernosum. In the proximal urethra, the neoplasm may involve the urogenital diaphragm, rectum, prostate, and bladder neck by direct extension.[5]

The penile and glanular urethra are drained by the inguinal nodes. The bulbar, membranous, and prostatic urethra drain to the external iliac, internal iliac, obturator, and presacral chain.[22] In general, anterior lesions drain to inguinal nodes, whereas posterior lesions, including bulbar lesions, drain to pelvic lymph nodes. However, anterior lesions may drain to pelvic nodes and posterior lesions to inguinal nodes, depending on the exact location of the lesion and whether contiguous structures are involved.[2,20] Unlike patients with penile cancer, clinical lymphadenopathy in males with urethral cancer is usually indicative of cancer spread rather than inflammation.[23]

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic and Staging Work-up

The most common presenting symptoms of cancer of the male urethra are a palpable mass and urinary tract obstruction,[23,24] often manifested by discharge, dysuria, pain, and hematuria.[15]

Male urethral cancer differs from penile cancer in that clinical evidence of lymphadenopathy in the groin or pelvis represents metastasis in over 75% of cases.[24] Posterior urethral tumors are more often associated with extensive local invasion and distant metastasis. The most common sites of distant metastases are the lungs, liver, and bones.[24]

FIGURE 8

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of a Male Urethral Cancer

Work-up of a male with suspected urethral cancer includes cystourethroscopy, CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, chest x-ray, and retrogradeurography. An MRI scan is useful in evaluating the extent of local disease (Figure 8).

Staging

The TNM staging system for cancer of the male urethra is shown in Table 1.

Treatment

Surgery-Because of the aggressive nature of this disease, conservative surgical therapy should only be offered to highly selected patients. Local excision, fulguration, or transurethral resection are considered for patients who have low-grade, low-stage, preferably solitary lesions.[25]

Partial penectomy entails amputation of a portion of the penis with a 2-cm margin around the tumor area. Patients selected for this procedure have a low-stage distal urethral lesion and must have a normal proximal urethra. Involvement of the corpus spongiosum or corpora cavernosa may be a contraindication to this procedure.[25]

Patients who are not candidates for partial penectomy because of the location or size of disease are treated with radical penectomy, with or without en bloc resection of the scrotum and anterior pubis and cystoprostatectomy. Using primary surgery for male urethral cancer, Dinney et al[26] reported that 52% of patients had no evidence of disease over a mean follow-up of 50 months. Survival was poorest (25% disease-free survival rate) in patients with bulbomembranous carcinomas.

Radiation Therapy-Data are limited with regard to the role of radiation therapy in male urethral carcinoma. Heysek et al[27] reported on 10 patients with urethral carcinoma, 5 of whom were treated with radiation alone. Local control was noted in four of the five patients treated.

Ticho et al[28] treated one patient with unilateral inguinal and pelvic lymphadenectomy and a combined course of external-beam and interstitial radiation therapy. The total dose to the urethra was 6,940 cGy. At over 12 months, the patient was free of recurrence.

Raghavaiah[29] described four patients treated with external-beam therapy. Two patients with distal lesions were free of disease 4 and 5 years, respectively, after doses of 5,000 cGy for 5 weeks and 5,500 cGy for 5½ weeks.

Because of the scarcity of patients treated with radiation therapy for cancer of the male urethra, definitive recommendations are difficult to make. As with cancer of the penis, if external-beam therapy alone is used for a patient with urethral cancer, a reasonable dose would appear to be 4,000 cGy in 4 weeks to the whole penile shaft, followed by a boost of 2,000 cGy in 2 weeks to the primary lesion and margin.

Chemoradiation-Similar to the situation in squamous cell carcinoma of the female urethra, case reports have shown the efficacy of fluorouracil, mitomycin and external-beam radiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the male urethra.[18,19] Baskin and Turzan[19] described a 66-year-old male with a large squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra who received fluorouracil-mitomycin with 4,000 cGy of radiation in 20 fractions to the primary site, groins, and deep pelvic nodes. Penile-preserving surgery followed, and no residual tumor was found in the surgical specimen.

Similarly, Licht et al[18] treated two males with combined-modality fluorouracil-mitomycin and external-beam radiation. The first patient received fluorouracil-mitomycin and 4,320 cGy of radiation and was free of disease at 98 months. The second patient with T2, N2 disease received the same chemotherapeutic agents and only 3,000 cGy of radiation in 15 fractions reoperatively. At surgery, the groin nodes showed no residual tumor, and the primary mass had shrunk 75% to 80% in size.

Oberfield et al[30] described two patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the bulbomembranous urethra whose disease was controlled with fluorouracil-mitomycin and external-beam radiation (4,500 cGy) after urinary diversion via suprapubic cystotomy.

Future efforts to manage squamous cell carcinoma of the male urethra with the combination of fluorouracil-mitomycin and modest doses (4,500 to 5,500 cGy) of external-beam radiation, with surgery reserved for salvage, are clearly warranted.

Prognosis

The overall 5-year survival rate is 43% for males with anterior urethral tumors and 14% for those with posterior urethral tumors. Among posterior urethral tumors, the prognosis appears to be better for prostatic as opposed to bulbomembranous tumors (29% vs 10%). Overall prognosis is related to depth of invasion, with early stages having a significantly better prognosis than late stages.[24]

As more experience is gained with chemoradiation, this prognosis may improve.

References:

1. Srinivas V, Khan S: Female urethral cancer-an overview. Int Urol Nephrol 19:423-427, 1987.

2. Narayan P, Konety B: Surgical treatment of female urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 19:373-382, 1992.

3. Mevorach R, Cos L, Sant’agnese AD, et al: Human papillomavirus type 6 in grade 1 transitional cell carcinoma of the urethra. J Urol 143:126-128, 1990.

4. Carroll P, Dixon C: Surgical anatomy of the male and female urethra. Urol Clin North Am 19:339-346, 1992.

5. Mostofi F, Davis CJ Jr, Sesterhenn IA: Carcinoma of the male and female urethra. Urol Clin North Am 19:347-358, 1992.

6. Hedden R, Husseinzadeh N, Bracken R: Bladder sparing surgery for locally advanced female urethral cancer. J Urol 150:1135-1137, 1993.

7. Hopkins S, Vider M, Nag S, et al: Carcinoma of the female urethra: Reassessment of modes of therapy. J Urol 129:958-961, 1983.

8. Hahn P, Krepart G, Malaker K: Carcinoma of female urethra. Urology 37:106-109, 1991.

9. Weghaupt K, Gerstner G, Kucera H: Radiation therapy for primary carcinoma of the female urethra: A survey of over 25 years. Gynecol Oncol 17:58-63, 1984.

10. Johnson D, O’Connell J: Primary carcinoma of female urethra. Urology 21:42-45, 1983.

11. Prempree T, Amornmara R, Patanaphan V: Radiation therapy in primary carcinoma of the female urethra: II. An update on results. Cancer 54:729-733, 1984.

12. Mayer R, Fowler J, Clayton M: Localized urethral cancer in women. Cancer 60:1548-1551, 1987.

13. Moinuddin Ali M, Klein F, Harza T: Primary female urethral carcinoma. Cancer 62:54-57, 1988.

14. Sailer S, Shipley W, Wang C: Carcinoma of the female urethra: A review of results with radiation therapy. J Urol 140:1-5, 1988.

15. Forman J, Lichter A: The role of radiation therapy in the management of carcinoma of the male and female urethra. Urol Clin North Am 19:383-389, 1992.

16. Bracken R, Johnson D, Miller L, et al: Primary carcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol 116:188-192, 1976.

17. Kalra J, Cortes E, Chen S, et al: Effective multimodality treatment for advanced epidermoid carcinoma of the female genital tract. J Clin Oncol 3:917-924, 1985.

18. Licht M, Klein E, Bukowski R, et al: Combination radiation and chemotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the male and female urethra. J Urol 153:1918-1920, 1995.

19. Baskin L, Turzan C: Carcinoma of male urethra: Management of locally advanced disease with combined chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and penile-preserving surgery. Urology 39:21-25, 1992.

20. Johnson D, Kessler J, Ferrigni R, et al: Low-dose combined chemotherapy/radiotherapy in the management of locally advanced urethral squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol 141:615-616, 1989.

21. Tran L, Krieg R: Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for a locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra: A case report. J Urol 153:422-423, 1995.

22. Levine R: Urethral cancer. Cancer 45(suppl 7):1965-1972, 1980.

23. Hopkins S, Nag S, Soloway M: Primary carcinoma of male urethra. Urology 23:128-133, 1984.

24. Srinivas V, Khan S: Male urethra cancer. A review. Int Urol Nephrol 20:61-65, 1988.

25. Zeidman E, Desmond P, Thompson I: Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. Urol Clin North Am 19:359-372, 1992.

26. Dinney CP, Johnson DE, Swanson DA, et al: Therapy and prognosis for male anterior urethral carcinoma: An update. Urology43:506-514, 1994.

27. Heysek R, Parson J, Drylie D, et al: Carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 134:753-755, 1985.

28. Ticho B, Perez-Tamayo C, Komak J: Primary carcinoma of the distal male urethra: A case treated with lymphadenectomy and interstitial radiation therapy. J Urol 139:1302-1303, 1988.

29. Raghavaiah N: Radiotherapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. Cancer 41:1313-1316, 1978.

30. Oberfield RA, Zinman LN, Leibenhaut M, et al: Management of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the bulbomembranous male urethra with co-ordinated chemoradiotherapy and genital preservation. Br J Urol 78: 573-578, 1996.