Exploring the Changing Diagnostic Criteria of Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome: A Case Report

A case study by Sahith Kumar Shetty, BDS, MDS, et al reviews the need for a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of patients with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome.

ABSTRACT

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, also known as Gorlin syndrome, basal cell nevus syndrome, and nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder. Its hallmark is an early onset of basal cell carcinoma. Additionally, the syndrome is characterized by a spectrum of distinct clinical attributes encompassing oral, skeletal, ophthalmic, neurological, and developmental aberrations. This condition arises due to anomalies in the Hedgehog signaling pathway, leading to constant pathway activity and uncontrolled growth of tumor cells. Early identification of the disorder through available diagnostic methods and clinical and radiological findings is crucial for accurate diagnosis, which subsequently leads to the formulation of an effective treatment regimen.

The purpose of this case report is to discuss the role of a dentist in early detection based on various author-prescribed criteria and the need for a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of patients with this syndrome.

KEYWORDS

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, basal cell nevus syndrome, Gorlin syndrome, basal cell carcinoma, odontogenic keratocyst, panoramic radiography

Introduction

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), alternatively referred to as basal cell nevus syndrome or Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (GGS), was initially documented in the scientific literature in 1894 by Jarisch and White. They outlined the fundamental characteristics of this syndrome and designated it NBCCS. However, it was not until the middle of the 20th century that NBCCS gained acknowledgment as a distinct and separate medical entity.1 In 1960, Robert James Gorlin and William Goltz identified the classical triad (consisting of multiple basal cell epitheliomas, keratocysts in the jawbones, and bifid ribs) that formed the diagnostic criteria for this syndrome.2The newly revised fifth edition of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) classification for hereditary head and neck tumor syndromes reaffirms the consistent utilization of diagnostic criteria that have been in place for more than 10 years.3 Although the existence of multiple odontogenic keratocysts (mOKCs) remains a significant criterion, there is still a lack of substantial evidence to determine the specifics of which individuals with multiple basal cell carcinomas should undergo dental screenings, including using panoramic radiographs to identify mOKCs associated with GGS.4

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome is a rare genetic condition inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. This disorder is marked by the presence of BCC, OKCs, and medulloblastomas, along with distinct features such as dyskeratotic palmar and plantar pitting, as well as a variety of skeletal and other developmental irregularities.4 This study presents the cranial, facial, dermatological, dental, and skeletal expressions of GGS in a young adult. The diagnosis of GGS was established through an assessment of clinical symptoms, radiographic characteristics, and histopathological examinations.

Case Presentation

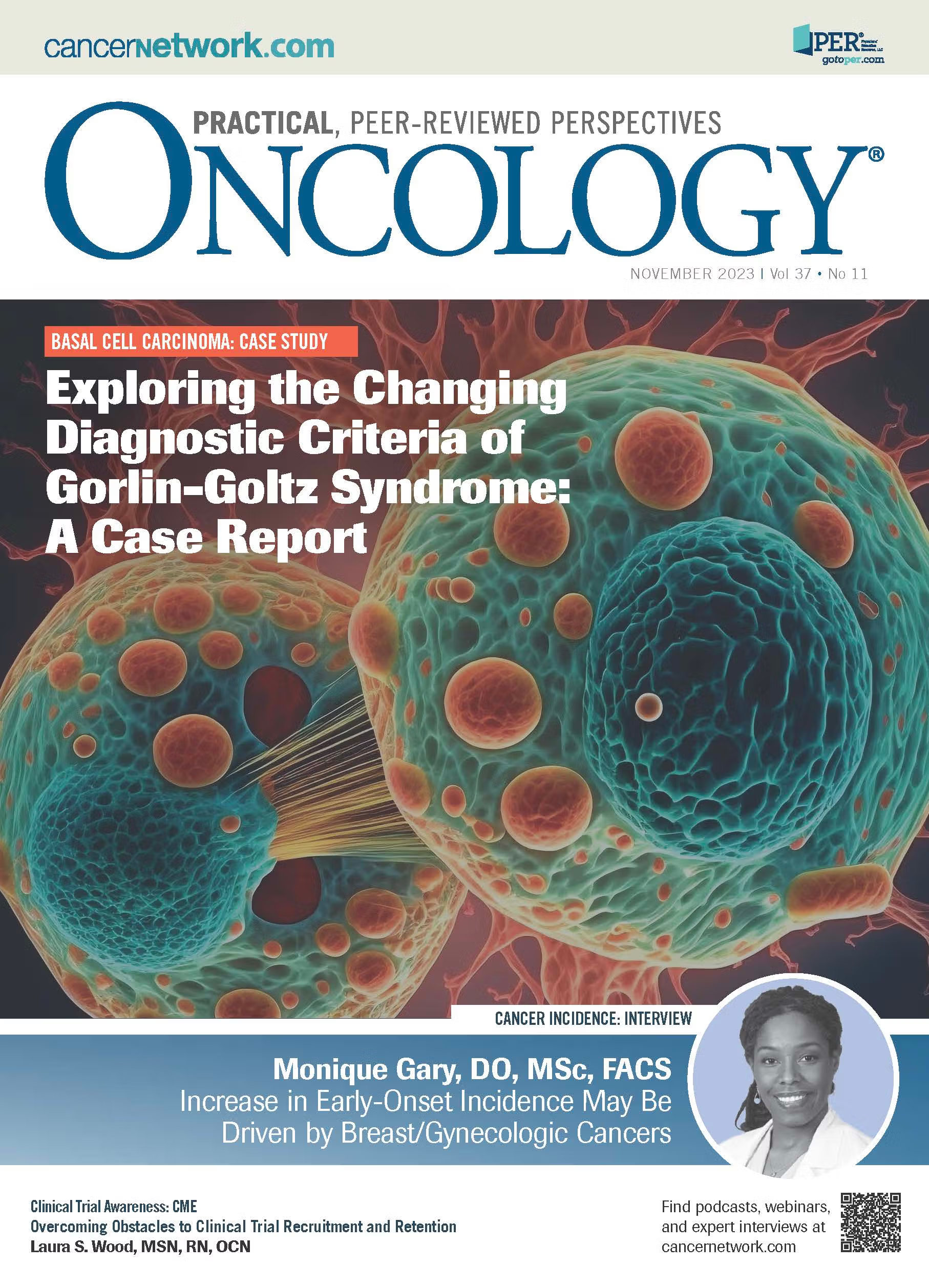

A 21-year-old man presented at an outpatient JSS Dental Hospital in Mysore, India. His chief complaint was of swelling in his right upper jaw for 15 days. The patient’s family history and medical history were not significant. The swelling was 2 × 1 cm in dimension, nonpitting, and nontender (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Intraoral Photograph Showing Solitary Palpable Swelling in the Back Close to the Midline

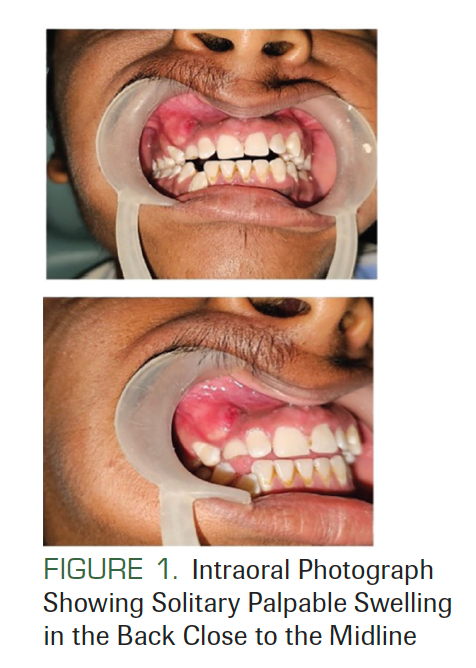

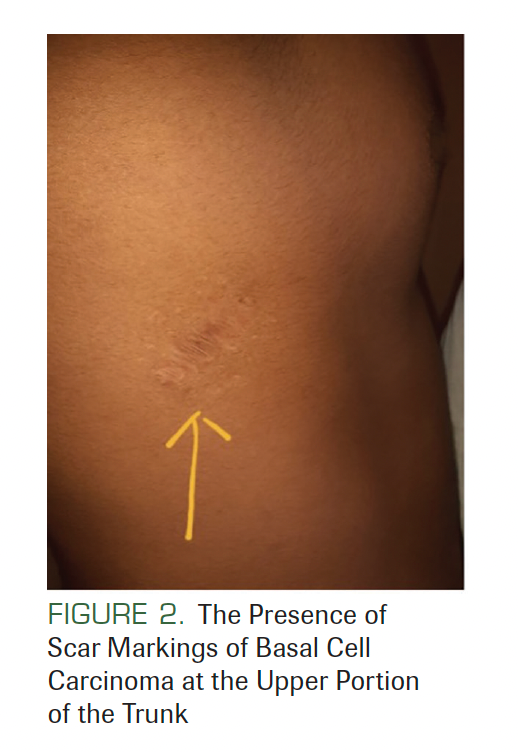

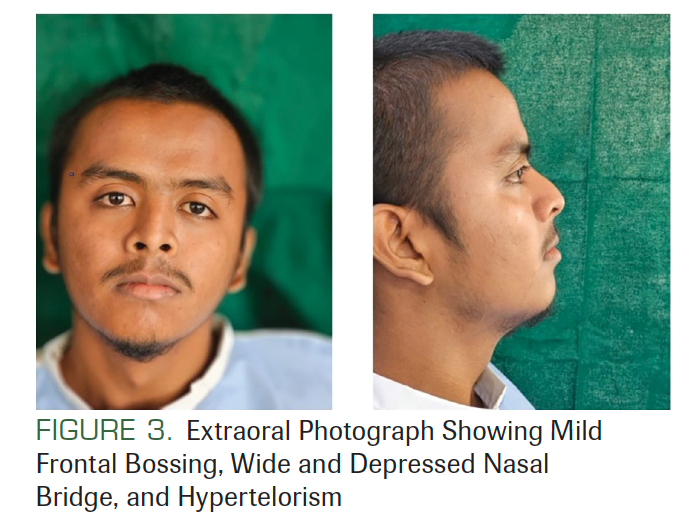

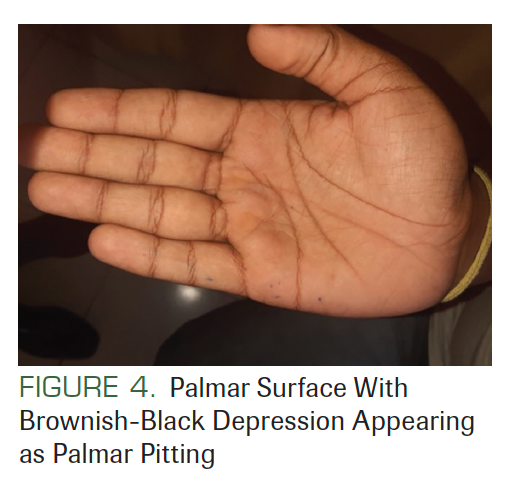

There was no lymphadenopathy, and no facial asymmetry was seen. He had a history of surgery at the back of his trunk due to a tumor that was diagnosed as BCC (Figure 2). On facial examination, mild frontal bossing, wide and depressed nasal bridge, and orbital hypertelorism were noted (Figure 3). Oral examination showed misaligned teeth with an open bite in the anterior region (Figure 1). Examination of the hands and palmar surface showed some brownish-black depression similar to palmar pitting (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2. The Presence of Scar Markings of Basal Cell Carcinoma at the Upper Portion of the Trunk

FIGURE 3. Extraoral Photograph Showing Mild Frontal Bossing, Wide and Depressed Nasal Bridge, and Hypertelorism

FIGURE 4. Palmar Surface With Brownish-Black Depression Appearing as Palmar Pitting

An orthopantomogram revealed multiple radiolucent lesions in both upper and lower jawbones. A large radiolucency with a well-defined margin was seen on both sides of the posterior ramus of the mandible and was approximately 3.0 × 2.5 × 3.0 cm. A large radiolucent lesion with a well-defined margin was seen in the anterior maxilla with impacted maxillary right canine teeth. A smaller radiolucent lesion between the root apices of the mandibular right canine and lateral incisor was also noted (Figure 5). Posterior-anterior and lateral views of the skull radiograph showed calcification of falx cerebri and bridging of sella turcica (Figure 6). Chest radiographs showed no abnormality. The provisional diagnosis of GGS was made based on the presence of multiple cysts in the jaws and extra oral features.

FIGURE 5. Orthopantomogram With Multiple Multilocular Radiolucent Lesions in the Maxilla and Mandible

FIGURE 6. Radiograph of the Posterior-Anterior and Lateral View of the Skull With Calcification of Bilamellar Falx Cerebri

Routine biochemical and hematological evaluations were carried out and showed normal parameters. An incisional biopsy of the cyst was sent for histopathological examination. On examination, the specimen demonstrated the presence of parakeratinized stratified squamous cell epithelium with corrugation that was 6 to 8 cell layers thick. The basal layer showed palisading nuclei and tombstone appearance. Epithelial connective tissue separation was seen. The underlying connective tissue showed odontogenic epithelial islands, blood vessels, and inflammatory cells. The lumen showed keratin flakes (Figure 7). All features were suggestive of odontogenic keratocyst or keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT).

FIGURE 7. H and E-Stained Section Shows a Lumen Filled With Keratin Flakes and Cystic Capsule Lined by a Corrugated Epithelium Having 6 to 8 Layers of Thickness

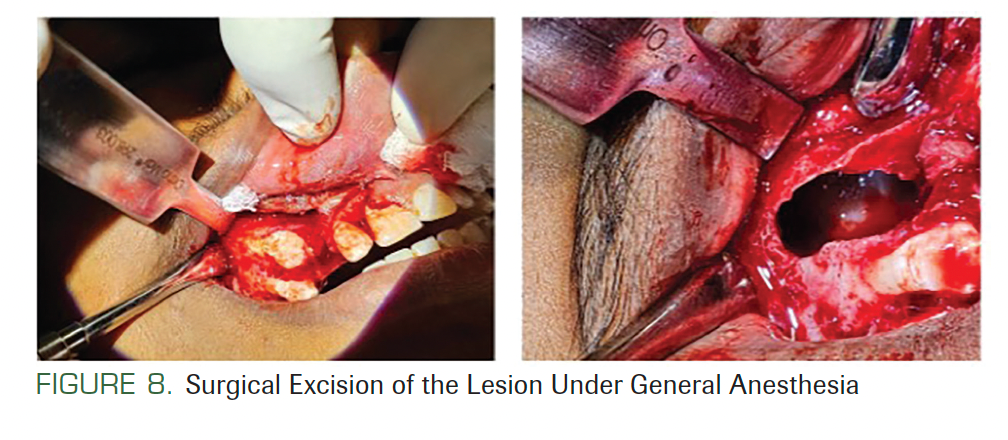

Under general anesthesia with all aseptic precautions, flaps were raised intraorally in all quadrants, one after the other. A surgical window was needed only in the third quadrant to reach the cyst. No vital structures were seen near the lesions. A surgical curette was used with saline irrigation for enucleating the cysts (Figure 8). The remnants of the cysts were removed using chemical cautery with Carnoy’s solution (2.5%) for 3 minutes and irrigation with saline. The cysts were enucleated from all 4 quadrants, followed by extraction of impacted teeth. The enucleated tissues were sent for histopathological evaluation. All the lesions were diagnosed as odontogenic keratocysts.

FIGURE 8. Surgical Excision of the Lesion Under General Anesthesia

The presence of 2 major signs (multiple odontogenic keratocysts and history of BCC) and 4 minor signs (calcification of falx cerebri, palmer pitting, bridging of sella turcica, and hypertelorism) confirmed that this patient had GGS. The patient is being followed up at 3-month intervals, and no recurrence of lesion has been noted.

Discussion

GGS is an autosomal dominant disorder. It is recognized by the occurrence of numerous BCCs and is accompanied by irregularities in the skeletal, ophthalmic, and neurological realms.4 This condition affects various systems and presents a wide array of indications and effects, giving rise to irregularities in the skin, skeletal structure, craniofacial features, nervous system, oropharyngeal area, genitourinary system, and heart. The primary clinical characteristics of GGS demonstrate a triad of BCC, multiple KCOTs, and skeletal anomalies.5

NBCCS, a seldom-seen condition inherited through autosomal dominance, stands out due to its most prominent feature: the emergence of cutaneous BCCs starting at a young age, usually at puberty, although some instances occur during childhood. The estimated occurrence of this condition ranges from 1 in 57,000 to 1 in 256,000 individuals, affecting both men and women without any gender bias. Although this disorder affects various ethnicities, only a small proportion (5%) of cases involve African, American, or Asian individuals. Interestingly, the diagnosis of NBCCS often happens incidentally when extracutaneous signs such as OKCs are present, rather than through the observation of BCCs.4,5The male-to-female ratio is 1:0.62 for OKCs not associated with NBCCS and 1:1 for OKCs in NBCCS. That is, simple keratocysts are more common in males, but more females with NBCCS develop OKCs.6 Similarly, the current case study presents a 21-year-old man exhibiting multiple OKCs that affected all 4 quadrants of the jaw.

The underlying mechanisms of NBCCS are elucidated through molecular changes in components linked to genetic mutations in elements of the Hedgehog pathway. This encompasses the PTCH1 gene, situated on chromosome 9q22.3, and the SUFU gene located on chromosome 10q24.3, which carries mutations that contribute to the disorder.1-3 The Hedgehog pathway serves as a critical regulator of cellular growth and differentiation during developmental processes. Additionally, it governs interactions between epithelial and mesenchymal cells across various tissues in embryonic stages. Although this pathway is usually quiescent in adults, when disrupted it can lead to elevated production of crucial proteins involved in cell proliferation and the development of cancer.5

BCCs are frequently aggressive in a clinical context and are more prevalent in individuals with lighter pigmentation and higher exposure to UV light. Although they mainly develop on the face, they can also appear on the trunk and limbs. These carcinomas generally emerge from puberty to middle age, although instances have been documented as early as 2 years of age. Many patients (70%-80%) exhibit additional recognized clinical features, including KOTs, dyskeratotic palmar and plantar pitting, and rib and spine irregularities, with early calcification of the falx cerebri. In a significant portion of patients, facial characteristics such as frontal bossing, hypertelorism, macrocephaly, and cleft lip and/or palate are also observed. Uncommonly, patients are at risk of desmoplastic medulloblastoma during childhood, along with various other neoplasms such as ovarian and cardiac fibromas, mesenteric keratocysts, rhabdomyosarcomas, and meningiomas.1,3

OKCs are the primary oral lesion of this condition, arising approximately 3 times as often in the mandible as in the maxilla. They frequently appear near the crown of an unerupted tooth. More than 80% of these cysts are unilocular in nature, although multilocular occurrences are also possible. Multiple KCOTs are the most reliable signs of GGS, particularly during the initial 2 decades of life. Histologically, these lesions present a uniformly thick squamous epithelial lining, typically with 5 to 10 layers of cells, featuring parakeratosis and basal/parabasal cell palisading. They are often accompanied by satellite tumors. Epithelial lining is commonly notable for high Ki67 proliferation index, p53 immunopositivity in basal and suprabasal cell layers, and loss of heterozygosity at various loci.3 In the current scenario, jaw cysts can present as multiple OKCs, possibly alongside impacted teeth, affecting all jaw quadrants. These cysts may exhibit unilocular or multilocular radiolucent characteristics. Clinical manifestations can include pain in the presence of swelling.

Early detection of the syndrome makes it possible to minimize the childhood and adult complications related to GGS. Furthermore, those who test negative for a known familial PTCH1 mutation before or immediately after birth can be removed from the surveillance program in the neonatal period. Patients with a known PTCH1 mutation should be informed about the possibility of early prenatal testing and termination of an affected fetus, and about the possibility of preimplantation genetic testing. All first-degree relatives of patients with a known mutation should be offered predictive molecular genetic testing.5

An echocardiogram can reveal cardiac fibromas. A neurological examination and measurement of head circumference are recommended every 6 months together with an annual MRI of the brain until age 7 years, after which a medulloblastoma is unlikely to appear. Dental screening with an orthopantomogram of the jaw is recommended from 4 to 8 years of age until 40 years to detect jaw cysts. A total skin examination should be performed at least annually starting during puberty but may need to be done more frequently if rapidly evolving skin lesions are present. Ovarian fibromas can be detected in the first and second decades by an ultrasound scan.5

Radiological examinations are pivotal for diagnosing GGS. Approximately 60% of patients exhibit distinctive dysmorphisms such as macrocephaly, protruding forehead, and facial milia. Skeletal irregularities can include fused or cuneiform vertebrae, hemivertebrae, and kyphoscoliosis, which may be evident. Additionally, facial dysmorphisms such as cleft lip/palate, macrocephaly, oral pathologies, and anomalies are commonly observed.6

Standard treatment strategies for odontogenic lesions that arise within

the jawbones include as follows4:

- simple enucleation of the lesion;

- enucleation combined with bone curettage, with or without the use of cytotoxic chemicals applied topically;

- complete resection in an en bloc manner, potentially followed by bone reconstruction;

- marsupialization procedure; and

- decompression of the lesion.

Given the often substantial tumor burden, individuals with NBCCS may undergo numerous excisions, leading to significant disfigurement. Besides surgical approaches, conventional therapies for localized disease involve applying agents such as 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod topically. Radiotherapy is not recommended for patients with NBCCS.1

The reported recurrence rate for OKC in the literature varies from 12% to 62.5%, influenced by factors such as duration, growth pattern, the inclusion of ortho- or parakeratinized epithelium lesions, and association with basal nevus syndrome. The possible reason for this wide range is likely the inadequate and incomplete removal of the primary lesion, although the exact cause remains uncertain.2,4

Postsurgery follow-up periods for OKC differ, with approximately 6 months for children and 1 year for adults. Recurrence observation spans 1 to 10 years, involving regular orthopantomography every 6 months for young patients and cone beam CT when doubts arise or anatomical structures need assessment. Follow-up for adult and older patients tends to be longer.4

Evolution of Early Diagnosis of GGS Based on the Criteria

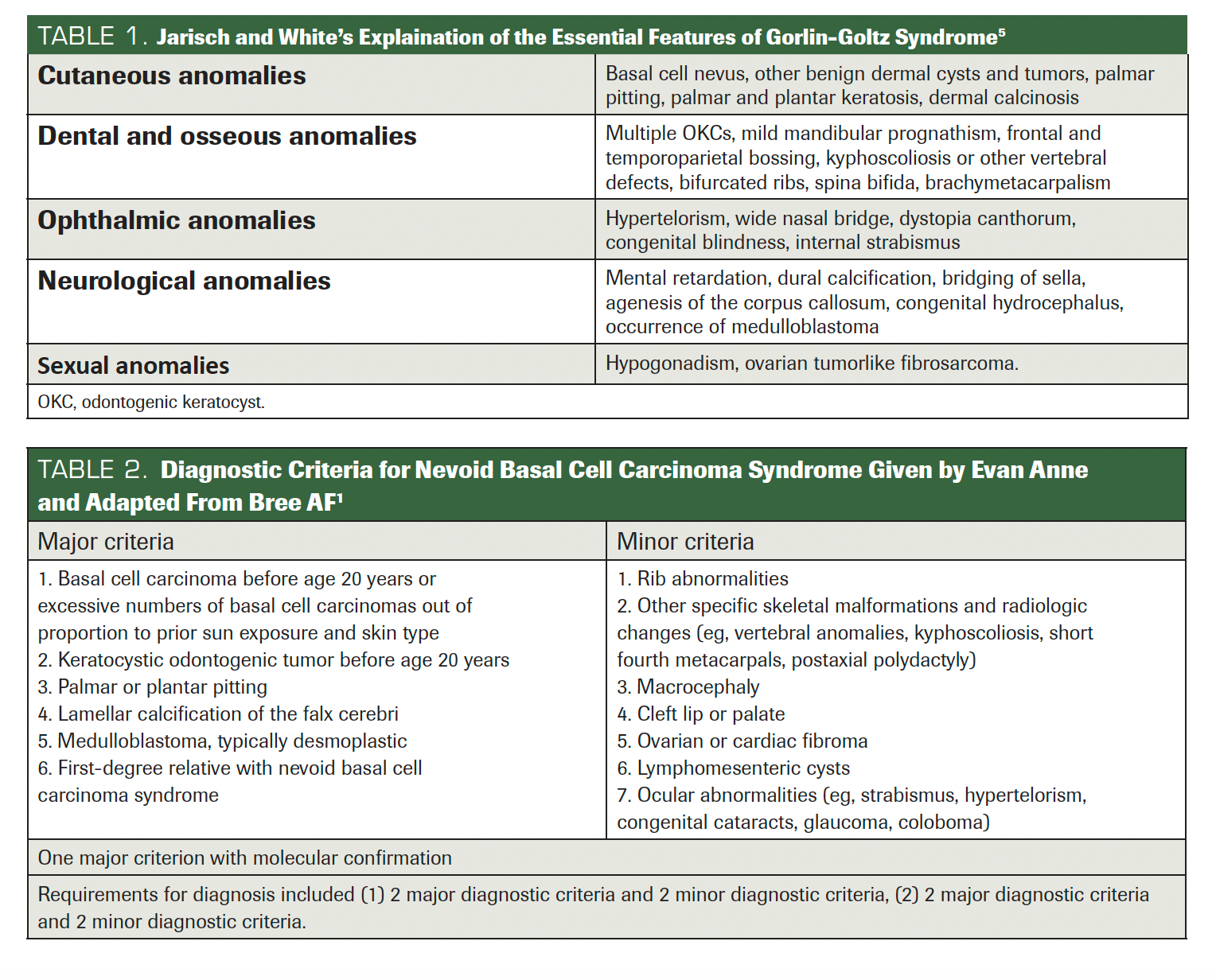

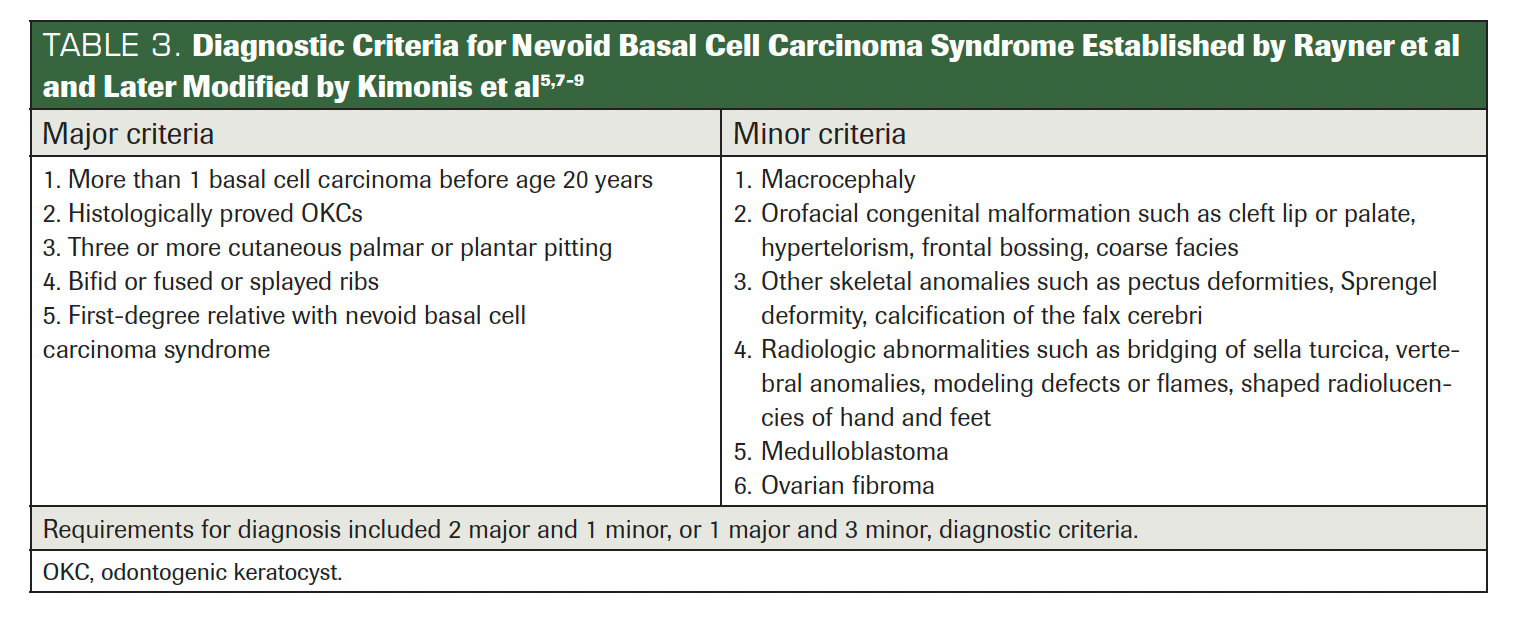

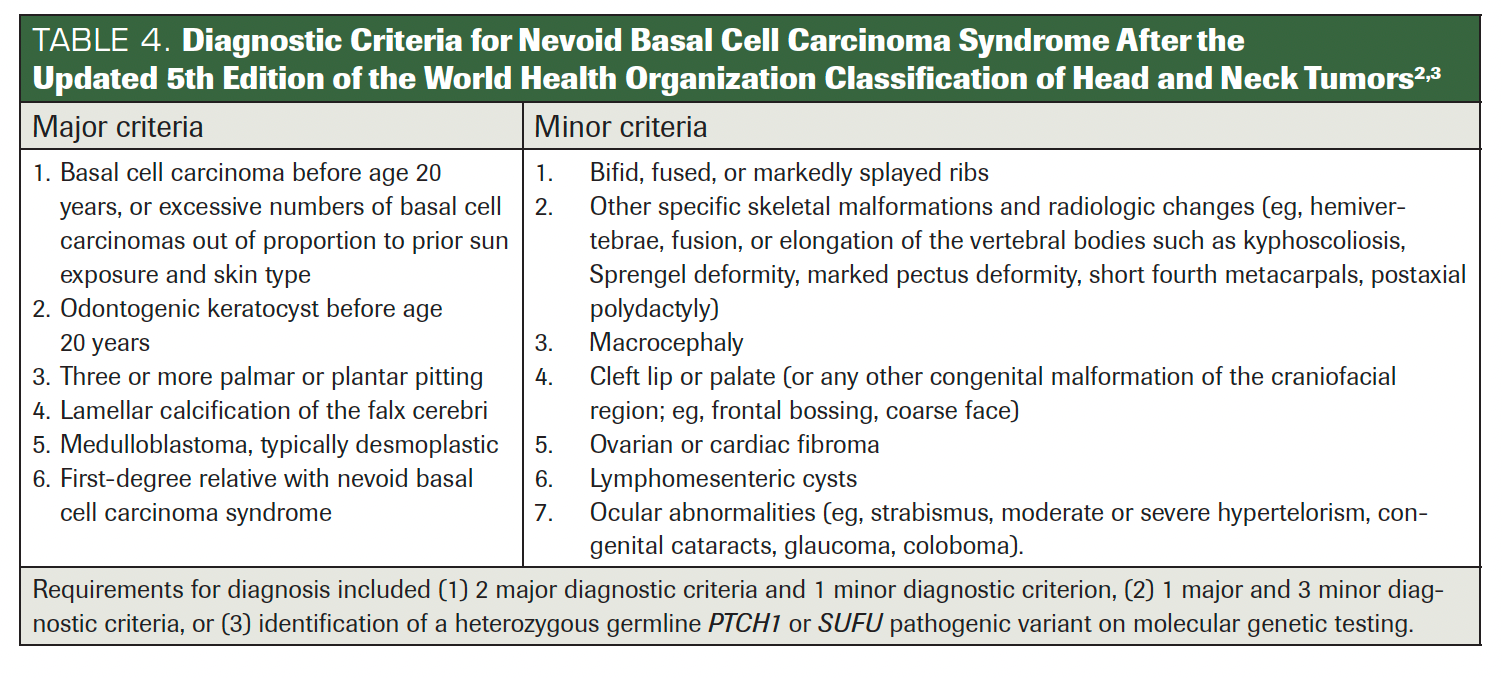

Since 1894, numerous criteria have been proposed to diagnose GGS. Initially, Jarisch and White outlined essential features and termed it NBCCS (Table 1).5 In 1960, Robert James Gorlin and William Goltz identified the classical triad (multiple basal cell epitheliomas, keratocysts in the jaws, and bifid ribs) that confirmed the syndrome’s diagnosis. Evans et al originally defined the diagnostic criteria for NBCCS in 1993, later reviewed by Manfredi et al. In 2011, Bree et al suggested that for a GGS diagnosis, a minimum of 2 major and 2 minor, or 1 major and 3 minor criteria, must be met. He also suggested confirming the syndrome with molecular investigations (Table 2).1 Rayner et al further refined the triad, asserting that for diagnosis, cysts should be present in combination with falx cerebri calcification or palmar/plantar pits.9 Kimonis et al in 1997 adjusted this to require either 2 major or 1 major and 3 minor criteria for diagnosis (Table 3).5,7-9 Presently, WHO recommends considering the diagnostic criteria for GGS if multiple basal cell carcinomas and/or OKCs occur before age 20 (Table 4).2,3

TABLE 1. Jarisch and White’s Explaination of the Essential Features of Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome

TABLE 2. Diagnostic Criteria for Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome Given by Evan Anne and Adapted From Bree AF1

TABLE 3. Diagnostic Criteria for Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome Established by Rayner et al and Later Modified by Kimonis et al5,7-9

The current paper highlights the proposed diagnostic criteria for this syndrome and establishes the surveillance recommendations for these patients with the goal of early intervention to decrease morbidity and mortality because the syndrome may have potentially lethal complications in early childhood. A multispecialty health professional such as a dermatologist, neurologist, neurosurgeon, family physician, geneticist, or dentist needs to facilitate timely assessment through diagnostic criteria as well as laboratory evaluation.

TABLE 4. Diagnostic Criteria for Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome After the Updated 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors

Conclusion

GGS is a rare autosomal dominant disorder that involves multiple organ systems, including the skin, ophthalmic, cardiac, and jaws. Knowledge of the maxillofacial manifestations is important for early diagnosis of this syndrome so that optimal treatment can be given and progression to a threatening condition curbed. Early diagnosis requires early radiographic and clinical assessment. Multidisciplinary management of the disorder enhances life quality and symptom treatment.

Given the multisystem involvement of GGS, recognizing major and minor diagnostic criteria is vital. Clinicians identifying syndrome-associated morphological traits can prompt germline screening, aiding identification of at-risk individuals and genetic counseling. Genetic insights can guide therapy and surveillance approaches.

Disclosure: The authors have no significant financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

Corresponding Author

Vidya G Doddawad, BDS, MDS

Associate professor

Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology

JSS Dental College and Hospital

A constituent college of JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research

Mysore-570022

Email ID: drvidyagd@gmail.com

Authors’ contributions

VGD: Concept, writing, and literature search for the manuscript

SS, SS: Review, data collection, and supervision of the manuscript

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Bresler SC, Padwa BL, Granter SR. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(2):119-124. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0706-9

- Ramesh M, Krishnan R, Chalakkal P, Paul G. Gorlin-Goltz syndrome: case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19(2):267. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.164557

- Nosé V, Lazar AJ. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: familial tumor syndromes. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16(1):143-157. doi:10.1007/s12105-022-01414-z

- Spadari F, Pulicari F, Pellegrini M, Scribante A, Garagiola U. Multidisciplinary approach to Gorlin-Goltz syndrome: from diagnosis to surgical treatment of jawbones. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;44(1):25. doi:10.1186/s40902-022-00355-5

- Larsen AK, Mikkelsen DB, Hertz JM, Bygum A. Manifestations of Gorlin-Goltz syndrome. Dan Med J. 2014;61(5):A4829.

- Mehta D, Raval N, Patadiya H, Tarsariya V. Gorlin-Goltz syndrome. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(2):279-282. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.129064

- Kumar NN, Padmashree S, Jyotsna TR, Shastry SP. Gorlin-Goltz syndrome: a rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9(3):478-483. doi:10.4103/ccd.ccd_96_18

- Tandon S, Chauhan Y, Sharma M, Jain M. Gorlin-Goltz syndrome: a rare case report of a 11-year-old child. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;9(3):264-268. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1374

- Krakowski AC, Hafeez F, Westheim A, Pan EY, Wilson M. Advanced basal cell carcinoma: what dermatologists need to know about diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(suppl 6):S1-S13. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.023