Nursing Strategies for Patients on Oral Chemotherapy

Oncology nurses play a pivotal role in educating the cancer patient who is about to commence oral chemotherapy. Increasing numbers of patients are receiving oral chemotherapy at home, and with this move to oral self-

ABSTRACT: Oncology nurses play a pivotal role in educating the cancer patient who is about to commence oral chemotherapy. Increasing numbers of patients are receiving oral chemotherapy at home, and with this move to oral self-administration, there has been a critical shift in responsibility of management from the provider to patient. Oral regimens pose new challenges in patient selection and education. Recognition of factors that affect patient compliance will be particularly important with oral chemotherapy. Strategy tools for the patient and provider will need to be developed to ensure optimal compliance and safety. [ONCOLOGY 15(Suppl 2):37-40, 2001]

Introduction

Nurses have always played a key role in the education and symptom management of patients undergoing chemotherapy. Now, with increasing numbers of patients self-administering oral chemotherapy at home, the support of the oncology nurse will be central to the effective management of these patients.

Patients often think of chemotherapy in terms of needles and intravenous lines, and there appears to be a wishful, but unfortunately false, perception that oral chemotherapy is going to be essentially nontoxic. Patients are inclined to think of it as the "cancer pill" and assume it will be similar to taking a vitamin or some over-the-counter headache remedy. Unfortunately, although the side-effect profiles of many oral chemotherapy agents are relatively favorable, serious systemic side effects can still occur, making early recognition with prompt intervention critical.

It is imperative that oncology nurses become familiar with new oral cytotoxic agents, such as the fluorinated pyrimidine analogues capecitabine (Xeloda) and UFT (Orzel [uracil, tegafur]). The primary focus must be to develop educational strategies to ensure patient understanding of medication administration, potential side effects, and self-care measures. This article will outline the active role that nurses must play in the management of patients who are self-administering oral chemotherapy.

Patient Selection

Appropriate patient selection is central to the successful and safe administration of any chemotherapy. In this area, oral regimens pose new challenges to patients and providers. Oncology nurses can play an active role in the identification of appropriately motivated patients for these self-administered therapies.

Compliance

To a large degree, an appropriate patient can be defined as a patient who is likely to exhibit adequate compliance. Compliance is reflected in many aspects of patient behavior over and above compliance with the dose and schedule. Compliant patients are responsible about keeping their scheduled appointments and are able to accurately answer questions regarding symptoms and side effects. These are patients who call when they suspect something is wrong, and who go to the doctor’s office or the emergency room when they have a fever.

With oral chemotherapy, "good patient behavior" takes on a new dimension. These patients still need to keep their scheduled visits, but they may need to contact the physician or nurse sooner when side effects (that may possibly warrant a treatment break) develop at home. If side effects are left unreported, necessary dose adjustments may not be made, and serious consequences can occur that can impact their life and further therapy.

TABLE 1

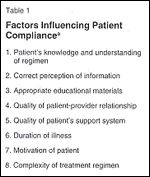

Factors Influencing Patient Compliance

Oncology nurses who are involved with patients taking oral chemotherapy must understand what factors affect compliance and how identification of these factors can aid in the development of educational strategies that will help assure patient compliance. Cameron[1] has identified several specific factors involved in promoting compliance with a therapeutic regimen. These and other factors are outlined in Table 1.

Compliance is affected by the patient’s knowledge and understanding of the specific regimen. The information must be perceived correctly, and to that effect, educational materials must be at an appropriate level of understanding for patient comprehension.

The quality of the patient-provider relationship also can profoundly affect compliance. The patient needs to feel comfortable with his or her physician or nurse in asking questions and reporting side effects. A patient’s support system-including family, friends, or home care nurses-also greatly influences the likelihood of compliance with therapeutic regimens. Is there someone to remind the patient to take his or her medication? Are caregivers in the home aware that they need to notice and inquire about side effects or clinical changes?

Compliance will also be influenced by each patient’s pre-existing beliefs and attitudes about health, disease, and medical treatments. These can affect not only how the patient follows his or her drug schedule, but also what he or she is willing to report or discuss regarding complications and side effects.

Compliance may be variable over time, with motivation and actual compliance potentially diminishing with the increasing duration of a patient’s illness. The complexity of the regimen will also affect the patient’s ability to comply.

Additional Factors in Patient Selection

Other factors in patient selection must include a patient’s physical limitations, especially in elderly patients. These limitations might include limited sight and limited manual dexterity in handling pills. Also, older patients are more likely to be taking multiple oral medications, and the addition of oral chemotherapy to this patient’s regimen may not be feasible, either due to the increased complexity or potential drug interactions.

A last consideration in patient selection is simply the patient’s ability to tolerate an oral medication. One must evaluate whether or not a patient is able to swallow pills and whether there is adequate gut function and absorption.

Who Monitors the Treatment?

Self-administered oral chemotherapy greatly shifts responsibility for dose monitoring and adjustments from the provider to the patient. There are many favorable aspects to this degree of patient empowerment, but there are also potential dangers.

In traditional parenteral chemotherapy, the healthcare provider has far greater control of dose and dose adjustments. The physician and nurse determine the presence or absence of side effects at office visits, and make judgments about dose adjustments. With oral chemotherapy, the patient-to some degree-is responsible for making dose adjustments in his or her own therapy; eg, the patient must decide whether to continue taking medication in the face of mild to moderate side effects. Perhaps more importantly, the patient must decide whether to withhold medication in the presence of more severe side effects, not knowing that failure to do so could result in substantial, and even life-threatening, toxicities. The important thing is to stress to the patient that it is important to call his/her physician or nurse at any sign of a symptom or side effect.

The Role of the Oncology Nurse

As educators, it will be a challenge to oncology nurses to provide the training and support to ensure the safety of patients taking on the responsibility of taking oral chemotherapy at home. The oncology nurse’s responsibilities include patient education, symptom management, and proactive follow-up.

First and foremost, patients need to know the correct dose and administration schedule.

Next, the toxicity profile of the oral agent needs to be discussed. Finally, the importance of early recognition of side effects and prompt reporting need to be stressed.

Patients are often reluctant to notify the nurse of side effects because they fear that their therapy may be interrupted or their dose will be lowered.

Patients will be helped if they can understand the importance of early reporting. This can be remedied by simply explaining to patients that

1. Most side effects resolve with a brief interruption of therapy.

2. Any necessary dose reduction is simply a customization of dose to that individual’s needs.

3. A dose reduction does not necessarily lessen the chance of antitumor effects.

Strategy Tools

Patient Strategy Tools

FIGURE 1

Diary and Symptom Management Log

A diary with a symptom management log (Figure 1) is an effective tool to help promote compliance and safe administration. This diary is given to the patient at the initial teaching session and can be reviewed at subsequent visits. It enables the patient to jot down the time the dose was taken, number of pills taken, and any experienced side effects. A key at the bottom of each page acts as a prompt for the patient to record side effects. Also, a monthly calendar can be used as a visual guideline in mapping out the overall treatment schedule. In addition, a chemotherapy fact card for the specific drug can be developed. This can include the mechanism of action, early and late side effects that may be experienced, and reasons to call his or her doctor or nurse.

Finally, many patients use a weekly pill dispenser to organize their daily doses. Prompts, such as a spouse, alarm clock, watch, or even hand-held computer such as a Palm Pilot, may be used to remind patients to take their medication.

Provider Strategy Tools

Specific prescription forms tailored to oral chemotherapy also can be developed by the caregivers. These forms can indicate the patient’s height, weight, body-surface area, calculated dose per square meter, and actual total daily dose. This added information would permit the pharmacist to verify doses, thereby reducing prescription errors.

FIGURE 2

Drug Accountability Form

In clinical trials, drug accountability forms are often used for documentation of the total number of dispensed pills (Figure 2). Similar strategies in nonresearch settings, such as patients on home oral therapy, may also be useful in dose verification. Examination of drug containers during return visits can help ensure that patients have completed their therapy. Dispensing only a single cycle of an oral agent is common and perhaps helps avoid overdoses. Follow-up visits after each cycle, even in the absence of reported toxicities, are useful to maintain close supervision of the patient and to permit early detection of clinical toxicities or deterioration.

Proactive nursing follow-up is critical with home-based therapy. Oncology nurses can effectively reinforce patient education through telephone triage, which includes reviewing the patient’s medication schedule from his or her home, monitoring adherence, evaluating early side effects, and implementing appropriate symptom management. If oral therapy requires interruption secondary to toxicities, increased telephone monitoring will be necessary, as will consultation with the treating physician. Through all of these activities, the oncology nurse concurrently continues to empower patients to become active participants in their own care.

Other Considerations

Additional self-administration pitfalls can pose a problem in oral chemotherapy. The occurrence of nausea and vomiting can seriously compromise the delivery of oral therapy. Routine antiemetics, such as prochlorperazine (Compazine), metoclopramide (Reglan), ondansetron (Zofran), or granisetron (Kytril), can be used as needed.

For some patients, there is also an anxiety component associated with taking numerous pills. An anxiolytic agent, such as lorazepam (Ativan), may be very effective in these patients, and may also provide some antiemetic effect. Also, it is common for patients to occasionally miss a dose of oral chemotherapy. In these instances, it must be stressed not to double up on the next dose.

Finally, patients often have a lack of appreciation for the potential seriousness of not reporting toxicities that develop. It is critical that patients and their families leave the oncologist’s office realizing the importance of early recognition of side effects.

Conclusion

The primary responsibilities of the oncology nurse are to facilitate patient education, communication, and follow-up. These roles are of vital importance in the management of ambulatory oral chemotherapy. It is important to realize that these roles do not end when the patient leaves the clinic. The oncology nurse may have to act as a liaison, not only with the patient, but with homecare providers, community pharmacists, and/or homecare nurses.

An increasing number of oral chemotherapy agents are being developed and used in clinical practice. Home-based therapy can offer many patient advantages. A sense of increased flexibility and autonomy can be an emotional boost for patients. However, such patients require careful monitoring and oncology nurses will continue to play a significant role in the safe and effective management of these patients.

Questions and Answers

Sunil Sharma, MD: You could argue that compliance can only decrease off trial. Even the best supporters of oral chemotherapy acknowledged that the compliance would be at least fractionally if not significantly lower in the real life setting in that it is just hard to have the kind of relationship you have with patients on a clinical trial.

Daniel Haller, MD: You could give the same argument for using the Mayo clinic regimen, where you will see charts that come to you for review where patients start off on a 50% dosing of a standard regimen, to make it easy. I think we have to put the same burden on intravenous treatments-that people do not always give optimal therapy.

Dr. Sharma: The other concern is patients continuing to take suboptimal doses. That is a different concern than patients who do not come back. Continuing to take self-modulated dosing is another concern that is a little different than not appearing after taking 5 days of therapy.

Leonard Saltz, MD: In particular trials of parenteral medications we have actually had situations where a patient deliberately concealed toxicity that she was having because she was afraid that if she told us about the toxicity we would cut her dose and she thought that would be a terrible thing. We found out about it the next week when she was in the hospital with grade 4 toxicity. One certainly worries about that mentality in any situation.

John Marshall, MD: I think that is where most of the patient education is being targeted now-not to encourage people to keep taking their medication on time but to tell them when to put on their brakes.

Dr. Saltz: It really depends a lot on all the other factors-education, socioeconomic status, and so on. Probably patients who come with the Palm Pilots are pretty good at getting it right and understanding the directions. That is, unfortunately, the minority.

Dr. Marshall: You are in a position to see patients because they are going on clinical trials. In a private practice setting, there is no nurse/educator. You do not get that education until you are sitting in the chair with an IV in your arm.

Paulo Hoff, MD: What you need are a television, a VCR, and a tape with instructions.

Deborah Semple, RN, MSN, OCN: I think that if oral chemotherapy regimens are here to stay, the chemotherapy nurses are going to have to be brought on board. In our institution, we will be doing an in-service on oral chemotherapy. It is a patient population that the nurses will not see anymore right away but they may see them later on if the patient goes on to a clinical trial.

References:

1. Cameron C: Patient compliance: Recognition of factorsinvolved and suggestions for promoting compliance with therapeutic regimens. JAdv Nurs 24:244-250, 1996.