Recap: A Review of the Treatment Landscape in Multiple Myeloma

A panel of experts discusses the treatment approaches to three clinical cases of multiple myeloma in the context of data presented at recent meetings and reviews how it can be applied to daily clinical practice.

Rafael Fonseca, MD

Mayo Clinic

Phoenix, AZ

Amrita Krishnan, MD

City of Hope

Duarte, CA

Krina K. Patel, MD, MSc

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Caitlin Costello, MD

University of California San Diego Health

San Diego, CA

At an Around the Practice® program hosted by CancerNetwork®, experts spoke about the rapidly evolving landscape of treatments in multiple myeloma. The discussion was led by Rafael Fonseca, MD, who is the director for Innovation and Transformational Relationships, and Mayo Clinic Distinguished Investigator at the Mayo Clinic campus in Phoenix, Arizona.

Panelists included Amrita Krishnan, MD, executive medical director of hematology, director of the Judy and Bernard Briskin Multiple Myeloma Center, and a professor in the Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation at City of Hope in Duarte, California; Krina K. Patel, MD, MSc, associate professor in the Department of Lymphoma/Myeloma in the Division of Cancer Medicine at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas; and Caitlin Costello, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of California San Diego Health in San Diego, California

The Evolving Treatment Paradigm in Multiple Myeloma

Fonseca: How do you think about treatment selection for frail patients with multiple myeloma? (Patient Case 1)

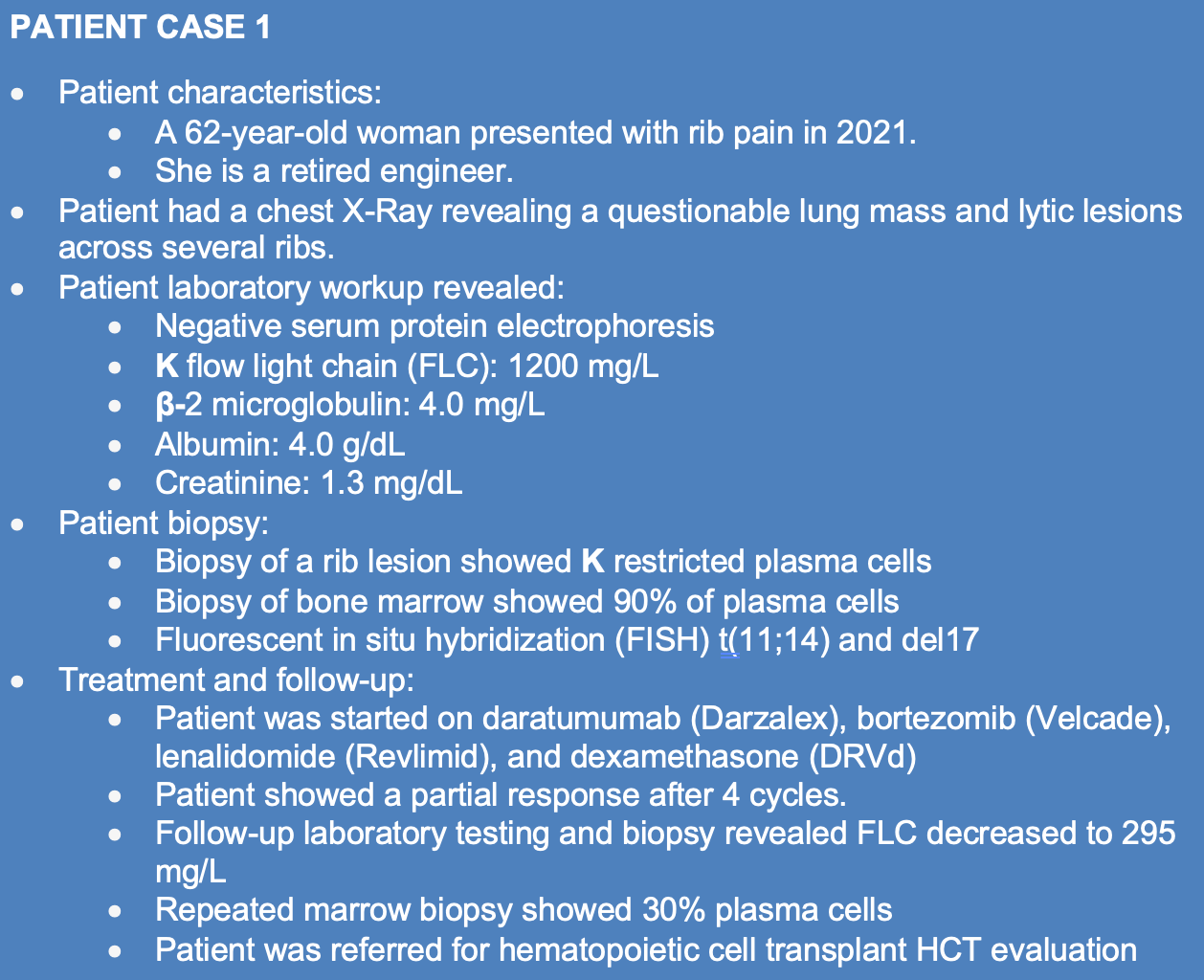

Patient Case 1

Patel: The definition of frailty varies among clinicians. We’re aggressive at MD Anderson—we feel most patients can tolerate [autologous stem cell] transplant.

Renal insufficiency [alone] is not a reason for transplant ineligibility, but if you have an older patient with comorbidities [who’s taking] 5 or more drugs for other conditions, they’re at a higher risk of other AEs. Performance status [also] tells you a lot. When I see a patient who can’t physically walk into my clinic [because] they’re in a wheelchair [from] severe neuropathy or something else, I don’t imagine I can reverse that. Patients like that are at higher risk for infections [and other toxicities]. Those are the kinds of patients I won’t take to transplant.

Fonseca: What are your thoughts on recent data from the MAIA trial?

Costello: The MAIA trial compared triplet chemotherapy using DRd vs doublet chemotherapy using just lenalidomide and dexamethasone [Rd]. Over the last few years, more data has emerged, and [the triplet] keeps looking better and better. [New data has shown] a large difference between the 2 in progression-free survival [PFS] as well as overall survival [OS].1 [The trial] examined an older group of patients [who were] truly transplant-ineligible, excluding, for example, patients who have deferred transplant. This is very relevant to thinking about patients like this. We can save lives by placing our older and frailer patients on this triplet regimen.

The remaining question is how to balance the toxicities with the success of the treatment. [When examining] quality of life, the toxicity of DRd appears to be manageable. We expect further updates as the data mature.

One of the studies presented this year at the 19th International Myeloma Society [IMS] Annual Meeting investigated if there was an optimal duration of therapy with DRd. Patients who received the triplet for at least 9 months, [and especially those who received it for] 18 months, experienced a substantial improvement in PFS. DRd produces deep responses overall, but if patients can tolerate 18 months of therapy, they’ll reap the largest benefit.2

Fonseca: What were the results of the subset analysis of MAIA examining frail patients?

Patel: The analysis classified patients as fit, intermediate, or frail, and then grouped the fit and intermediate patients together.3 The investigators examined the frail patients separately to test outcomes [and found that] the frail patients may have a slightly lower PFS. However, frail patients still performed better with DRd vs Rd. They haven’t reached PFS yet in the triplet arm, and it’s about 30.4 months in the doublet arm. Again, frail patients respond better for longer [to DRd]. The toxicities [of the 2 treatments] were very similar.

In the 8 years that I’ve been part of the faculty at MD Anderson, I’ve never used a doublet because these studies started emerging as I joined. I always choose a triplet regimen. I [would only] use a doublet regimen for a patient who couldn’t [tolerate the triplet] due to severe lung disease or someone to whom I couldn’t give a CD38-targeted antibody.

Fonseca: What about quadruplet therapies?

Patel: That’s a matter of undertreating vs overtreating. When providing care to some of my older, frailer patients with high-risk disease like plasma-cell leukemia, I try to administer a quadruplet because I know this is my one chance to get them the therapy they need and produce a response.

Other than that, the triplets [are supported by] such great data that adding more AEs by using quadruplets [seems senseless]. The question is: will quadruplets provide any benefit over DRd? The median PFS with DRd is so great. How much benefit will quadruplets provide, and how much will they take away? I only [consider quadruplet therapy for] high-risk, highly frail patients.

Krishnan: I have a very fit patient in their 80s who is still working and has 17p deletion as I assess their disease. I treated them with DRd until I received the results of their FISH test. [After that], I struggled with their disease until I administered the quadruplet. [This decision was driven by] data from a study on attrition rates showing that 50% of patients with transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma did not receive their second line of therapy.4

Fonseca: What are your treatment goals when using one of these regimens for frail, transplant-ineligible patients? (Patient Case 2)

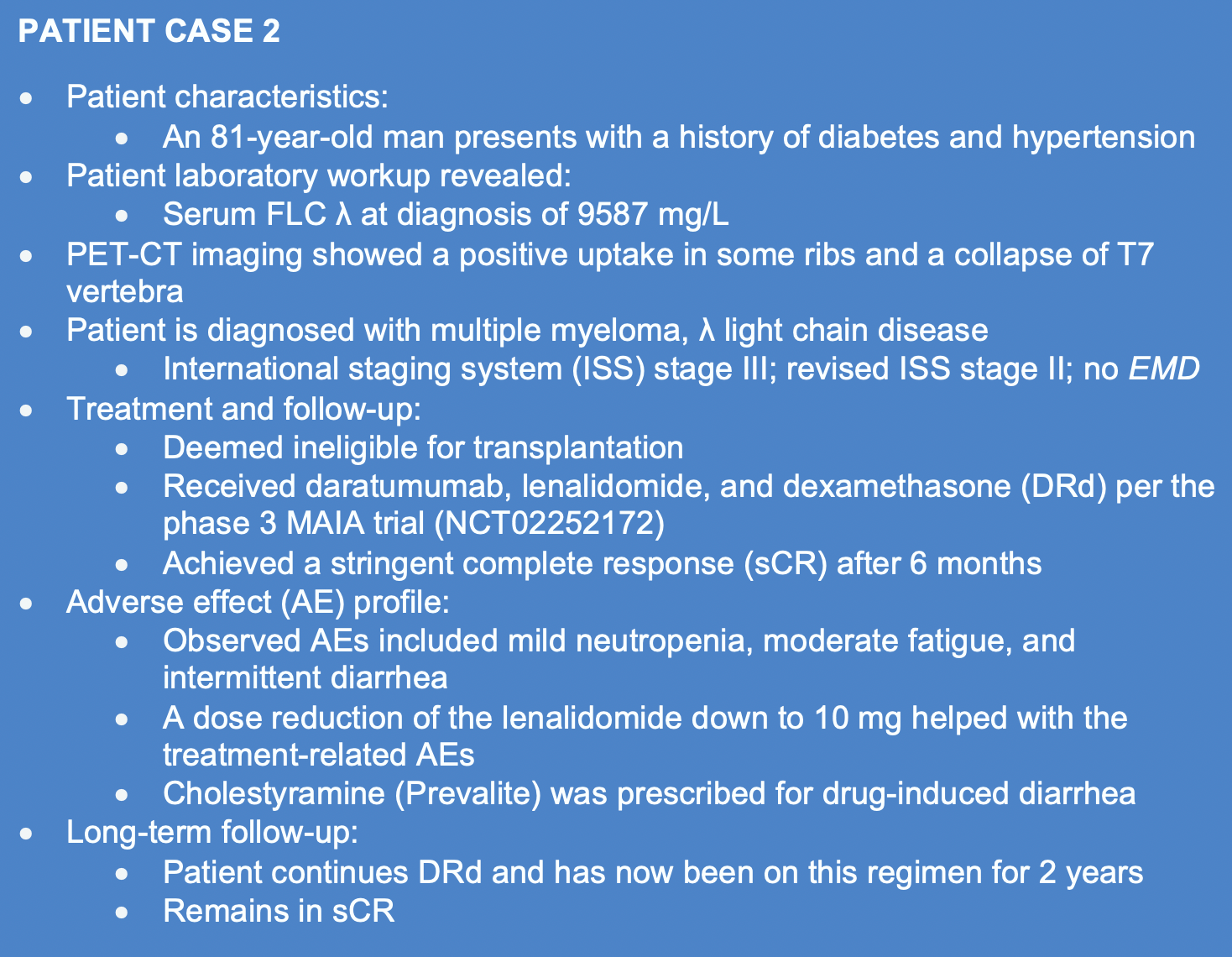

Patient Case 2

Costello: In an ideal world, the goal is no different than in the case of a transplant-eligible patient who’s still trying to achieve a deep and durable response. It’s just a matter of finessing the best results without excess toxicity. I never want the drugs to be worse than the disease.

Realistically, not every 80-year-old is the same. An 81-year-old patient employed full-time may very well tolerate quadruplet therapy, and for patients like that, it’s worthwhile to go big from the start in the hope of making a real dent in the disease. You can perform a reliable ‘sniff test’ on some patients: as soon as they walk in, you can tell they’re not going to tolerate quadruplet therapy. Even with high-risk disease, sometimes triplet therapy is best. It’s a very careful balance between the successes of the treatment and the toxicity.

Fonseca: What are your thoughts on transplant suitability in patients aged 70 years to 75 years?

Krishnan: That’s a challenging group. There’s some retrospective data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research [CIBMTR] showing that younger and older patients tolerate transplants at roughly equal rates.5 However, that’s a very selective group of patients.

It’s not a question of early vs delayed transplant. I always say [to patients]: if we’re going to do it, this is the ideal window of time. There are certain patients who elect to do it. I’m a little more liberal than most, [but] it’s not wrong to consider a non-transplant approach as well. In our practice, it’s about 50/50 transplant vs non-transplant.

Fonseca: What should be the duration of therapy?

Krishnan: For some patients, I continue therapy while dropping the elements that appear to cause the most severe AEs, [such as] steroids, and keeping the antibody.

Having said that, COVID changed many things. In the last couple of years, our practice has greatly shifted how we assess the risks of antibody therapy. We’ve recently been shifting back [to our pre-COVID tolerance of risk], but we’re currently somewhere between those 2 extremes. However, we try never to underestimate the risk of infection, especially in older patients.

Fonseca: How do we think about relapsed multiple myeloma? (Patient Case 3)

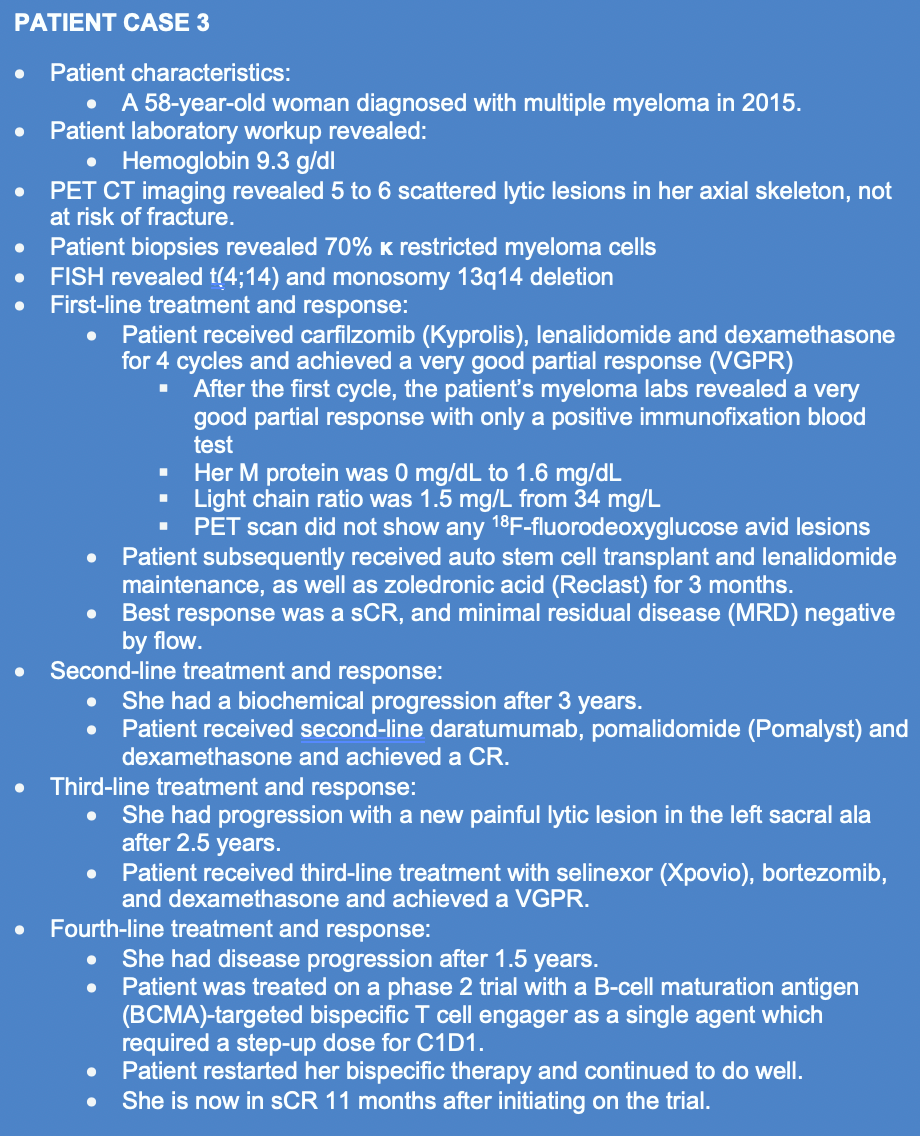

Patient Case 3

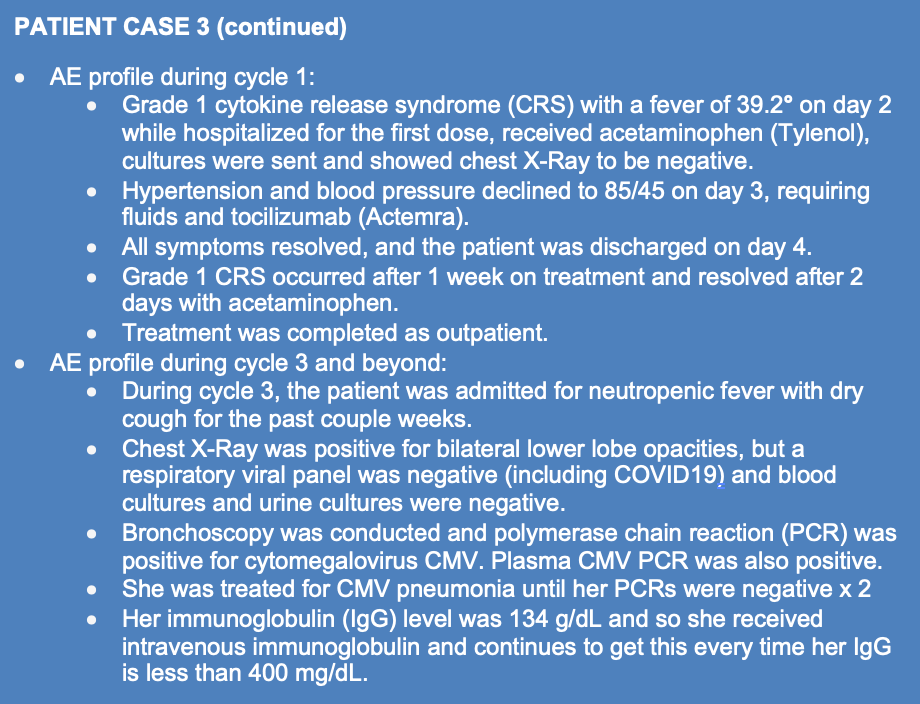

Case 3 cont.

Costello: It’s helpful to break down relapsed disease into early-relapse and late-relapse phases. The drugs available now can be lumped into 1 of those 2 phases. When selecting a patient’s second and third lines of therapy, for example, it’s important to switch drug classes from the frontline therapy, or at least to try new drugs.

For example, when thinking about second-line therapy, many transplant-eligible patients have been on lenalidomide maintenance for quite some time and would be great candidates for a CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody like daratumumab if they didn’t receive one upfront. That’s one way you could think about switching to a different drug class. You could switch them over to a carfilzomib–based regimen as well. Basically, now that they’ve spent time on an immunomodulatory imide drug [IMiD], they could go back on a protease inhibitor. Some patients may not tolerate carfilzomib, or they may have received it upfront. In that situation, you could switch back to the IMiD class instead.

In summary, [clinicians should pay attention to] drug classes, prior lines of therapy, and prior toxicities. For example, in patients who may have received bortezomib–based inductions, it’s important to think about any peripheral neuropathy [they may have experienced]. We have to tailor the regimen [to each patient] based on ECOG performance status, disease biology, and prior toxicities so we can achieve deep and durable remissions without excess toxicity.

Fonseca: Attrition is also very important when treating relapsed and refractory disease. There have been several recent studies on this issue, but if you examine real-world evidence, the proportion of patients that can finish each subsequent line of therapy is substantially lower [compared with trial populations]. Roughly 50% of transplant-ineligible patients can’t finish each succeeding line of therapy. In transplant-eligible patients, the number is [a little lower], around 30%, but that’s why it’s so important to put your best foot forward [in terms of treatment].

[One might be tempted] to save daratumumab [for a later line of therapy], but the reality is that we’re not waiting. We’re hoping to get years of disease control [with quadruplet therapy, with daratumumab], and then thinking about the relapsed and refractory disease [afterward].

There are also many patients who are exposed to lenalidomide nowadays. You can’t draw conclusions, but the trials of carfilzomib look better for the relapsed and refractory settings now that most people in the United States have received long-term lenalidomide after their initial therapy.

Bispecific Antibodies

Fonseca: What is the mechanism of action of bispecific antibodies like teclistamab [Tecvayli]? How have they performed in terms of efficacy?

Krishna: Bispecific antibodies have been game-changers. For the kind of patient described [in Case 3], the options for therapy used to be very limited before bispecifics.

Different antibodies target different elements in the myeloma cell. Teclistamab is BCMA–targeting; talquetamab is G-protein coupled receptor family C group 5 member D [GPRC5D]–targeting, and cevostamab is FcRH5-targeting. The BCMA-targeting bispecifics are the most prevalent and most developed.

In the phase 2 MajesTEC-1 trial [NCT04557098] of teclistamab, patients had a median of 5 prior lines of therapy and the response rate was 65%, which was astounding.6 Dr. Costello and I share some patients who have reached cycles 30 and 40 [on teclistamab]. The depth and durability of the responses are extremely encouraging. However, we’re still learning. I’m seeing infections I only used to see performing allotransplantation, like cytomegalovirus and pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Supportive care is very important to ensure success on these regimens.

Fonseca: What kind of data have we seen from the phase 2 CARTITUDE-2 trial [NCT04133636] on ciltacabtagene autoleucel [cilta-cel; Carvykti], a chimeric antigen receptor [CAR]–T cell therapy?8

Patel: At the 19th IMS Annual Meeting this year, [data from this trial] were presented [showing PFS wasn’t reached] after the last patient had been on therapy [with cilta-cel] for 2 years. This is a one-and-done medication, and it had a 95% response rate. Moreover, 2 years after treatment, more than 50% of patients are still progression-free. They haven’t had treatment in 2 years. To me, that’s phenomenal. Most patients [on that trial] have had CRS, but these were largely grade 1/2. This is a little worse than [the toxicities of] most bispecifics, but the rates of response and PFS have been extremely high. Hopefully clinicians will soon have more access to this therapy in the outpatient or standard-of-care settings.

Fonseca: We seem to be moving in that direction; 2 CAR-T cell therapies have received FDA approvals so far [cilta-cel and idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel; Abecma)].9,10

Patel: Indeed. The approvals will certainly help more patients access these treatments.

[Additionally], data from the phase 2 KarMMa trial [NCT03361748] showed that, for patients who received the targeted standard-of-care 450×106 dosage of ide-cel, the response rate was 81% and PFS was around 12 months.11 About 40% of these patients had a sCR and a median PFS of around 20 months. These are amazing responses without any ongoing therapy. As in CARTITUDE-2, there were many cases of grade 1/2 CRS, but these are very [manageable].

Doris Hansen, MD, presented real-world CAR-T consortium data on ide-cel at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting this year, and even though 77% of those patients wouldn’t have been eligible for KarMMa, their response rates were still 86%.12 These patients received the 450×106 dosage, so they have to be compared with the KarMMa patients who received the same. Their median PFS was lower; it was around 8.6 months. Nevertheless, this is 8.6 months in a group of heavily refractory patients with multiple comorbidities, so this was a great example of how well patients can perform [on these therapies] outside of clinical trials.

Transcript edited for clarity.

References

- Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(11):1582-1596. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00466-6

- Moreau P, Facon T, Usmani S, et al. Treatment duration and long-term outcomes with daratumumab in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma from the phase 3 MAIA study. Presented at: 19th International Myeloma Society Annual Meeting. August 25-27, 2022. Los Angeles, CA. Abstract OAB-039.

- Facon T, Cook G, Usmani SZ, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: frailty subgroup analysis of MAIA. Leukemia. 2022;36(4):1066-1077. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01488-8

- Fonseca R, Usmani SZ, Mehra M, et al. Frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by subsequent lines of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1087. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-07503-y

- Munshi PN, Vesole D, Jurczyszyn A, et al. Age no bar: A CIBMTR analysis of elderly patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2020;126(23):5077-5087. doi:10.1002/cncr.33171. Erratum in: Cancer. 2021;127(20):3904.

- Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, et al. Teclistamab in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(6):495-505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2203478

- Nooka A, Moreau P, Usmani S, et al. Teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) x CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): Updated efficacy and safety results from MajesTEC-1. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_supplement):8007. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.8007

- Cohen AD, Einsele H, Delforge M, et al. Updated clinical data and biological correlative analyses of ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma after 1-3 prior lines of therapy: CARTITUDE-2 cohort A. Presented at: 19th International Myeloma Society Annual Meeting; August 25-27, 2022; Los Angeles, CA. Abstract OAB-045.

- FDA approves ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. News Release. FDA. March 7, 2022. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://bit.ly/3Vzoil6

- FDA approves idecabtagene vicleucel for multiple myeloma. News Release. FDA. March 29, 2022. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://bit.ly/3VN2Rwu

- Munshi NC, Anderson LD Jr, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):705-716. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024850

- Hansen DK, Sidana S, Peres L, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel (Ide-cel) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): Real-world experience. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16):8042. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.8042

EP: 1.Induction Regimen Options for Patients with Transplant-Eligible NDMM

EP: 2.Selecting a Treatment Regimen for Patients with Transplant-Eligible NDMM

EP: 3.Measuring Treatment Response in Transplant-Eligible NDMM

EP: 4.First-Line Treatment Options in Transplant-Ineligible NDMM

EP: 5.Treatment Regimens for Frail Patients with Transplant-Ineligible NDMM

EP: 6.Goals and Duration of Treatment for Elderly Patients with Transplant-Ineligible NDMM

EP: 7.Currently Available Treatment Options for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

EP: 8.Novel Bispecific Agents in the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma

EP: 9.CAR T-Cell Therapy in Multiple Myeloma Treatment

EP: 10.Unmet Needs and Future Directions in Multiple Myeloma Treatment

EP: 11.Recap: A Review of the Treatment Landscape in Multiple Myeloma

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.