Recap: Testing, Treatment, and Timing in Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Experts review current treatments for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, centering their discussion around a patient case.

At a recent Around the Practice® program hosted by CancerNetwork®, an expert panel analyzed treatment options for a patient with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (CSPC), and in doing so, they reviewed the disease landscape more broadly. They touched on the utility of somatic testing and other genetic tests, the advantages of doublet vs triplet therapy, and the clinical relevance of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels.

The discussion was led by Alan H. Bryce, MD, and he was joined by Tian Zhang, MD, MHS; Benjamin H. Lowentritt, MD; and Daniel P. Petrylak, MD.

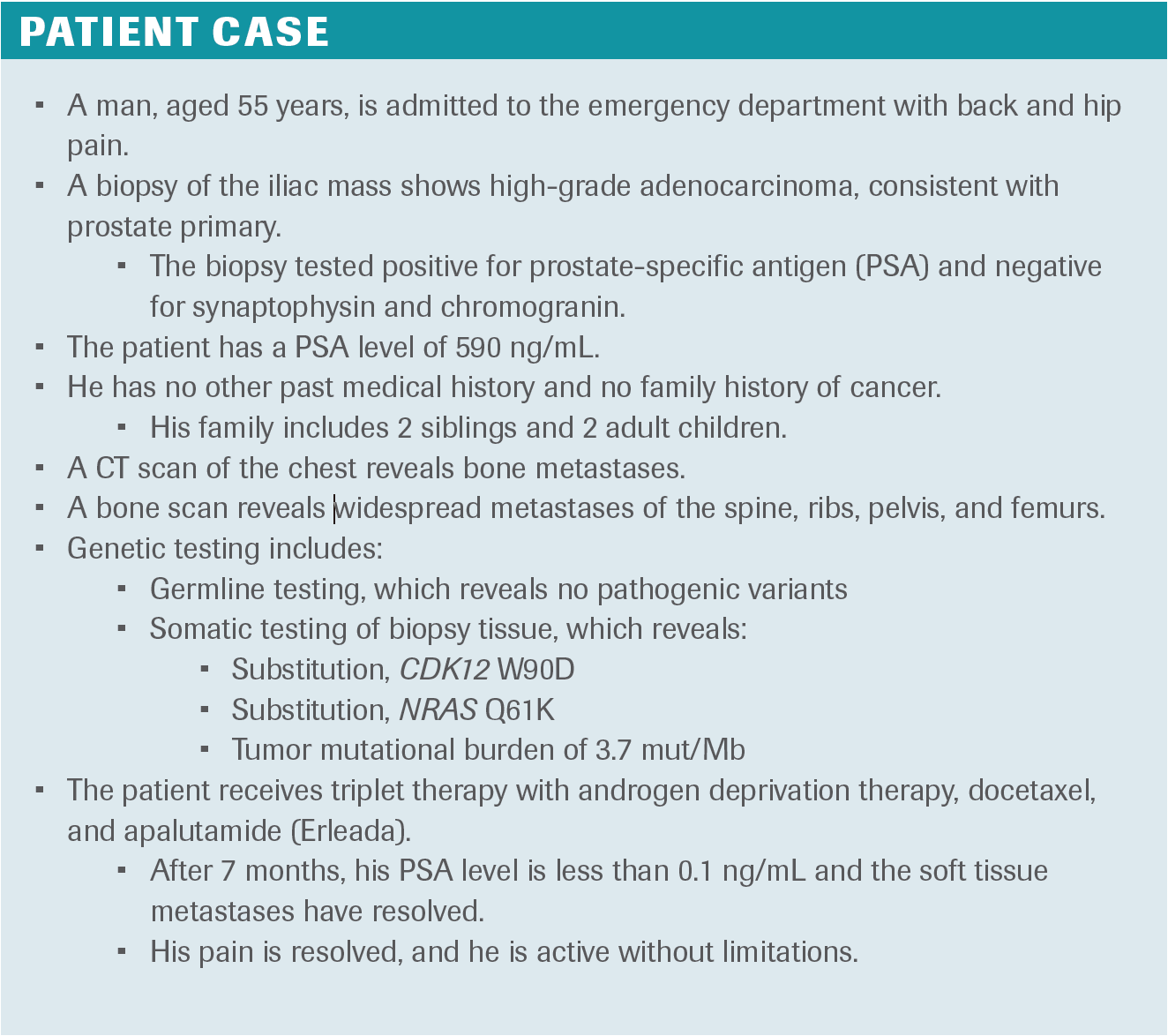

PATIENT CASE.

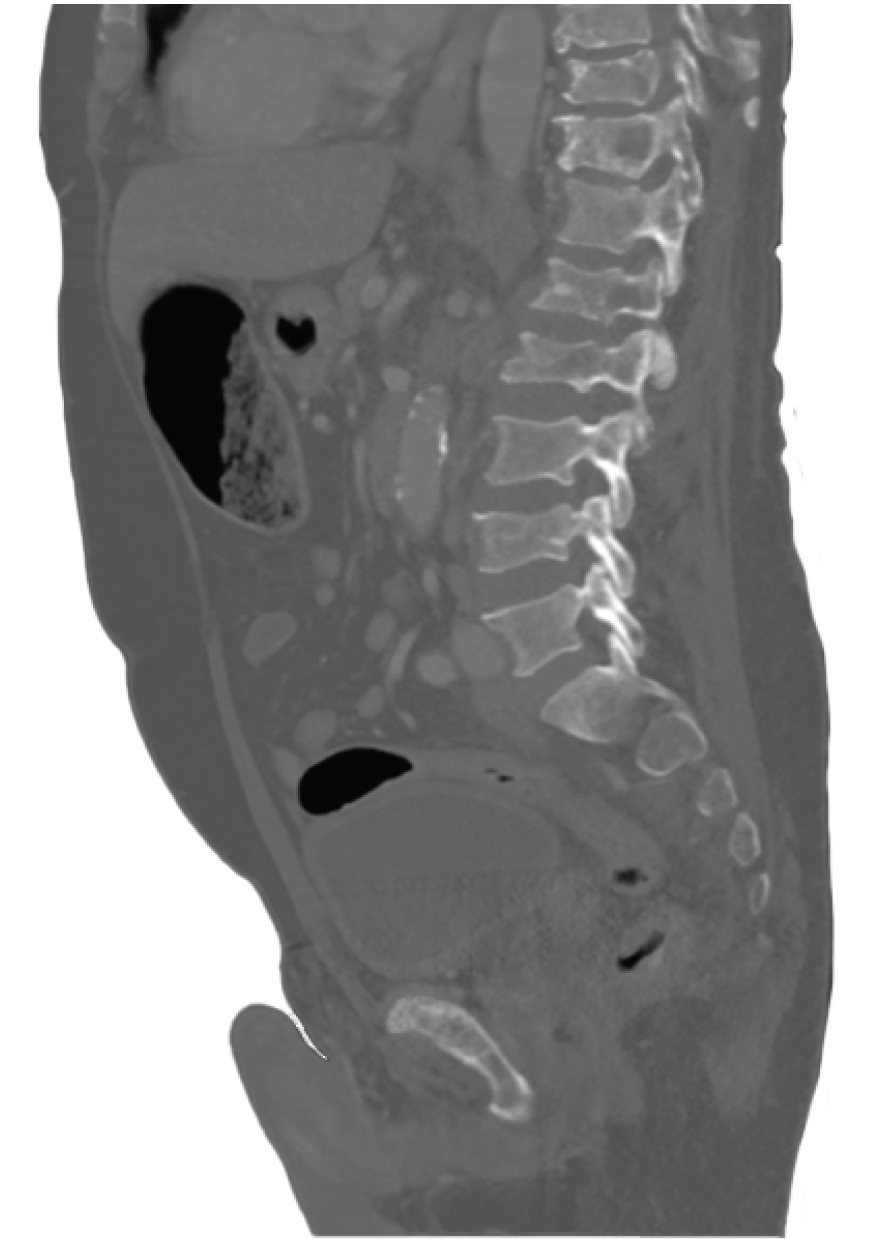

FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 2.

Testing to Determine a Diagnosis

BRYCE: What further testing would you want this patient to undergo if he came to your clinic?

LOWENTRITT: I’m interested in learning as much as I can from the tissue that we [already] have. I would send the biopsy specimen for further [somatic] testing to get any information we can out of the genetics from [that] fresh metastatic tissue. I would set up the patient to undergo germline testing as well.

BRYCE: How do you think about the pros and cons of somatic testing in this setting, and how do you talk them through with the patient?

LOWENTRITT: I don’t think any of us believe that the somatic information will be irrelevant as soon as we have more information about treating patients [with certain specific profiles] earlier. I’m preparing for the future, both academically and for this patient. If they have certain markers like BRCA2, you might suspect that their [treatment will] fail more quickly. Even if we’re not talking about pure predictive power regarding a specific treatment, there’s certainly [some degree of] prognostic value [to somatic testing].

[It’s also important] to get the complete picture. We know that only about half of the relevant genetic alterations, especially in the homologous recombination repair [HRR] pathway, will be in the germline setting, and at least half will be in the somatic [setting]. It’s critical to get this information when you have [access to] good, viable tissue. Personally, I know that the longer the tissue has been around, the harder it is to get a reliable result. It’s [therefore] valuable to get [somatic testing done] up front, even if you may not use [the information] immediately.

PETRYLAK: Somatic testing can be useful in clinical trials. The phase 3 TALAPRO-3 trial [NCT04821622] recently closed [enrollment]. TALAPRO-3 is examining talazoparib [Talzenna] in patients with DNA repair mutations. That’s one situation in which somatic testing can be useful.

Other targeted agents could be used again in clinical trials. We don’t have standard treatments that [targeted agents] would be useful in, but the androgen receptor [AR] degraders may work better in patients who have AR mutations. Again, however, those are for clinical trials.

[Somatic testing] would also give the patient a road map. If this patient progressed after hormones, [and] if he’s BRCA positive, [AR degraders] are one thing I would administer quickly. You would have that information at your fingertips, and [you wouldn’t] need to know what to do at that point. So, those are the advantages of somatic mutation panels.

BRYCE: What is the role of Prolaris or Decipher testing in these settings? Do they help with your decision-making? Do you find a use for them?

PETRYLAK: No, I don’t think they’d affect my decision-making. For localized disease, they might help, but [in this setting] they're not very useful. I’m going to [base my decisions more on] the patient’s volume of disease. Additionally, whether the patient has de novo or progressive prostate cancer after local therapy is also important. There are other [relevant] factors in the patient’s general medical condition. Those are the things that may affect what I do.

BRYCE: How would you discuss the results of this genetic testing with the patient? What would you tell them about these tests?

ZHANG: When I [discuss] genetic testing in the clinic, I often say that about 10% to 15% of [patients] will have [results that are] directly actionable [given] what we know today. [These actionable alterations include] HRR defects. In this case, it’s very interesting that he has a CDK12 alteration. We know that CDK12 plays a role in some recombination events and is thought to be somewhat associated with sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, genomic stability, and susceptibility to immune checkpoint inhibitors [ICIs].

That said, I don’t think it affects his immediate treatment decision-making. However, as my colleagues have said, these alterations can help us make decisions later.

Treatment Sequencing

BRYCE: We’re now in an era where clinicians have a wealth of different potential options for first-line treatment, as well as plenty of equipoise regarding how to select among the options for various patients. How would you select a treatment for this patient?

LOWENTRITT: It’s important to keep in mind who the patient is, where they are, and what we can really expect. This is a young patient. I won’t make any real assumptions, but presumably, this is a higher-functioning patient [who is] otherwise reasonably healthy. This is a patient with widespread disease, with high-volume, high-risk disease by any measure we would use.

As such, I would recommend triplet therapy for this patient. He seems to be an ideal patient for a combination of androgen deprivation therapy [ADT], docetaxel, and novel hormonal therapy. [Of course], patients need to have a discussion around [their treatment]. However, he seems to be a perfect candidate for that triplet.

For me, as a urologist, sometimes the major question is a patient’s fitness for chemotherapy. I’m not used to assessing whether a patient is chemotherapy fit or not. This patient’s condition certainly warrants a full discussion on the value of chemotherapy in this setting, [administered] along with one of the other agents.

BRYCE: How do you discuss these questions with patients?

ZHANG: In general, I tell them that we have many [potential] standard-of-care approaches. This patient is in his 50s, and 50 is the new 30, right? These patients are often fit and functional, and we want to keep them there. Often we talk about controlling the disease as quickly as we can and, in doing so, improving many of the symptoms [as well as] the patient’s quality of life. From a toxicity standpoint, with the taxanes, we talk a lot about neuropathy [and] suppression of the bone marrow. [However], in a young patient, the bone marrow is [hopefully] fine. This patient’s cytopenia issues will hopefully be manageable. Some men [also] ask about fatigue and hair loss. Those are the main things [we talk about]. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are less [commonly discussed], but they are also part of the toxicity profile.

BRYCE: How do you identify which patients will benefit most from triplet vs doublet therapy, and vice versa?

PETRYLAK: For triplet therapy, I’m first looking for a young patient who can tolerate treatment. Second, [I’m looking for someone] who has an aggressive disease as signified by de novo prostate cancer, visceral metastases, liver metastases, [or] more than 4 lesions on bone scan. Those are generally considered to be high-risk features in this patient [population]. The Gleason score might also be something I’d consider, especially if it’s a score of 10. Those are the factors that would lead me to consider giving a triple therapy to a patient.

If the [patient is] frail, or if I think the prostate cancer will be the secondary cause of their demise [behind] cardiovascular disease, I would [favor using] ADT plus another novel agent. [A patient like this] may not be able to withstand chemotherapy, and adverse effects [AEs] [must be considered].

Another issue is [deciding] how to select the right next-generation [antiandrogen therapy]. That’s based on AEs. Abiraterone acetate [Zytiga] has some known cardiovascular toxicity, identified by [a study from] Thomas Jefferson University [that showed] late cardiac events in patients treated with abiraterone.1 Patients [often] have to go on chronic steroids with abiraterone, which can cause skin issues. Liver function abnormalities [may be] another issue. [On the other hand], patients feel fatigued on enzalutamide [Xtandi]. They may feel somewhat less fatigued on apalutamide [Erleada], but that’s at the cost of rash or hypothyroidism. So, there are a lot of pros and cons to using [any of] the antiandrogens.

BRYCE: What is your preferred partner oral agent when giving triplet therapy? Moreover, how should we talk to patients about improvements in PSA levels?

LOWENTRITT: The PSA is still the only sign for most patients that they’ve ever had cancer. Even when they get to this patient’s stage, many have never experienced any symptoms, so PSA remains very important. We do have a lot of data now, [drawn from] several trials and even some real-world studies, showing that the depth of PSA decline predicts both [survival] and quality of life. We’re back to a point at which PSA is relevant. [However], we want to de-emphasize PSA to some extent and [avoid] creating PSA anxiety. We know that reaching a PSA of 90% or a PSA of 0.2 ng/mL or less both predict better responses in terms of survival and quality of life.

As for the first [part of this] question, you want to choose the [agent] that you’re most confident a patient can take for the longest time. It’s mostly AE driven. You certainly want to use the best data available when choosing [an agent for] the individual patient.

However, whether it’s sequencing or combination therapy or whatever you find yourself doing, [PSA] is an early signal in the first few months that you can talk to your patients about, and [you can use it to] potentially de-escalate some of their monitoring. This is what I’ve started doing when I see a very strong PSA response; I no longer see them monthly or every 2 months. [Instead], I might see them every 3 months and give them a bit of a break from the requirements of coming into the office. There’s still a lot we can learn just from PSA.

Determining Sufficient Time Periods for Treatment

BRYCE: Let’s say this patient relapsed today. What would you consider to be his treatment options at that point?

ZHANG: I think a lot about timing. [I think about] both depth of response and the timing of their progression. Can you tell me if this relapse is within 3 months of finishing chemotherapy, or is it a year-and-a-half out?

BRYCE: Let’s say this is 18 months out.

ZHANG: In those cases, I generally like to think about rechallenging with more chemotherapy. In a subset of patients, we might have a trial available for CDK12 alterations. We can also consider whether this portends some susceptibility to ICIs and try to get [one of them] off-label. In these postchemotherapy spaces, I also often think about lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan therapy [Pluvicto]. If the patient has prostate-specific membrane antigen uptake, [are they] a good candidate for lutetium-177?

In today’s climate, we would at least rechallenge with an alternative chemotherapy like cabazitaxel [Jevtana] before lutetium-177, but as we get more information from the phase 3 PSMAfore trial [NCT04689828] and others, we might consider using lutetium-177 in earlier settings.

Closing Thoughts

BRYCE: Where do you think the field is going in the first-line treatment of metastatic CSPC? Does anything on the horizon especially excite you?

LOWENTRITT: [I’m excited to] see how some of these agents can move to earlier [lines of therapy] in targeted populations. Even though we’re so successful with hormonal therapies and even though they’ve been so great in prostate cancer, anything with a different mechanism that we can [use to] either abbreviate or avoid some of those chronic hormonal therapy issues is exciting to me. [This might involve] using lutetium-177 or another radioligand therapy in earlier stages [or using] targeted therapies based on different biomarkers, not just PARP inhibitors. These are exciting times, and those [new therapies] will likely start to blossom over the next 3 to 5 years.

BRYCE: What advice would you give a collaborating community physician whose patients live far from the cancer center?

PETRYLAK: About half of our patients who are receiving next-generation androgens [do not receive] triplet therapy. Every patient needs to receive at least doublet therapy [that is] properly, from a medical standpoint, offered to them. Whether they receive chemotherapy or not will be related to the characteristics of the [patient’s] disease and the patient’s ability to travel to their physician. [However], at minimum, they should be offered next-generation sequencing, as well as the novel agents; [unfortunately], we’re just not seeing the uptick [in access] that we should be seeing with [these agents] across the country. That’s what I would say to care providers in rural areas.

BRYCE: Any other final thoughts?

ZHANG: I would [again recommend] sending for genetic testing when possible, especially for patients with metastatic disease, or even in the high-risk, localized setting. Per the guidelines, it’s important to test these [patients] and to find that 10% or 15% who might have actionable mutations and alterations. If we don’t test, we won’t find them.

As we gain access to more and more life-extending therapies, our patients are living longer [and longer], and I’m glad to be here for it. I’m glad to have a continuity of practice for these patients with prostate cancer.

REFERENCE

- Shah YB, Shaver AL, Beiriger J, et al. Outcomes following abiraterone versus enzalutamide for prostate cancer: a scoping review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(15):3773. doi:10.3390/cancers14153773

EP: 1.Patient Scenario 1: A 55-Year-Old Man With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

EP: 2.Newly Diagnosed mHSPC: Factors Used to Inform Treatment Selection

EP: 3.Selecting Between Doublet and Triplet Therapy in Newly Diagnosed mHSPC

EP: 4.mHSPC: Importance of Quality of Life and Multidisciplinary Care

EP: 5.mHSPC: Assessing Patient Response and Selecting 2L Therapy at Progression

EP: 6.Patient Scenario 2: A 65-Year-Old Man With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

EP: 7.Patient Scenario 3: A 75-Year-Old Man With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

EP: 8.Practical Considerations for Selecting and Administering Treatment in mHSPC

EP: 9.Future Directions in mHSPC Management: An Evolving Treatment Landscape

EP: 10.Recap: Testing, Treatment, and Timing in Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Prolaris in Practice: Guiding ADT Benefits, Clinical Application, and Expert Insights From ACRO 2025

April 15th 2025Steven E. Finkelstein, MD, DABR, FACRO discuses how Prolaris distinguishes itself from other genomic biomarker platforms by providing uniquely actionable clinical information that quantifies the absolute benefit of androgen deprivation therapy when added to radiation therapy, offering clinicians a more precise tool for personalizing prostate cancer treatment strategies.