The Role of Apalutamide in Patients With Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Neeraj Agarwal, MD, and Simon Chowdhury, MD, review final results from the TITAN study of apalutamide in patients with mCSPC and discuss the clinical implications of the findings.

The addition of an androgen signaling inhibitor to standard androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been proven to positively impact outcomes for patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) in multiple phase 3 studies, yet these newer combination treatments are used less frequently vs ADT alone in the real-world setting.1-2

In a recent Between the Lines discussion from CancerNetwork®, Neeraj Agarwal, MD; and Simon Chowdhury, MD, explored data from the phase 3 TITAN study (NCT02489318) that analyzed survival for patients with mCSPC who received apalutamide (Erleada) in addition to ADT vs ADT alone.3

“More than 50% of patients in the United States are receiving standard androgen deprivation therapy alone for newly diagnosed, metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer and that is not acceptable based on these data,” said Agarwal, a professor of medicine and director of the Genitourinary Oncology Program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“ADT alone isn’t enough. This is a lethal illness and apalutamide is an active drug,” Chowdhury, a consultant medical oncologist specializing in urological cancer at the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospitals in London, England, added. “We need to think about implementing this to benefit as many men as possible with this lethal disease.”

The first interim analysis for TITAN showed improved overall survival (OS) and radiographic progression-free survival (PFS),4 with the final efficacy and safety outcomes.

TITAN Study Outcomes

Patients treated on TITAN were randomized 1:1 to either 240 mg of apalutamide daily or matched placebo orally once daily in combination with continuous ADT.

Of the 525 patients in the apalutamide group and 527 in the placebo group, 257 (49.0%) and 358 patients (67.9%) discontinued study treatment, respectively, with most patients remaining alive and receiving subsequent life-prolonging therapy.

“Of these patients, the vast majority—almost 70% patients—received subsequent life-prolonging therapies,” Agarwal explained. “Based on these data, I can assume without doubt that this was a representation of what we do in our clinics.”

After 405 death events, of which 170 occurred in the apalutamide arm and 235 in the placebo arm, the OS analysis showed a significant 35% decrease in the risk of death in the apalutamide group (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53-0.79; P < .0001).

Median OS was not reached in the apalutamide arm, compared with 52.2 months in the placebo arm, and the 48-month OS rates were 65.1% and 51.8%, respectively.

“We can see that overall survival is 52 months [with standard ADT]. That is less than 5 years,” Chowdhury added. “These are young, fit men whose normal life expectancy would’ve been significantly longer than that.”

Both experts emphasized the importance of the data that emerged after adjusting for the 208 patients (39.5%) who crossed over from the placebo arm to receive apalutamide treatment after unblinding. After accounting for crossover, median OS in the placebo arm at 39.8 months was shorter than that of the original analysis by 12.4 months, with rates at 48 months of 65.2% in the apalutamide arm and 37.9% in the placebo arm. This translated to a 48% reduction in the risk of death with apalutamide vs ADT alone (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.42-0.64; P < .0001).

“If you take into account those 40% of patients who are on the placebo arm who crossed over to the apalutamide arm, the hazard ratio improves from 0.65 to 0.52,” Agarwal further explained.

“A 33% reduction in risk of death with apalutamide further [increases] to 50% when we adjust for patients [who crossed over from the] placebo arm to the apalutamide arm.”

Patients benefited from apalutamide treatment over placebo in prespecified subgroup analyses, specifically focusing on patients with high-risk and both high- and low-volume disease.

“All patients seem to be benefiting, whether they had high-volume disease or low-volume disease, had de novo metastasis or non–de novo metastasis, or were younger patients or older patients. That’s the overall message,” Agarwal explained.

The pair of experts then focused on the exploratory end point of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, which occurred in 26.3% and 65.3% of patients in the apalutamide and placebo arms, respectively. This translated to a significant reduction in the risk of PSA progression with apalutamide, marked by a 73% reduction in risk vs placebo (HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.22-0.33; P < .0001).

“PSA is so important in the clinic because when patients come in, they will be asking about it,” Chowdhury explained. “We all know PSA is prostate-specific antigen, but patients often refer to this as the ‘promoter of stress and anxiety.’”

Toxicity and Quality of Life

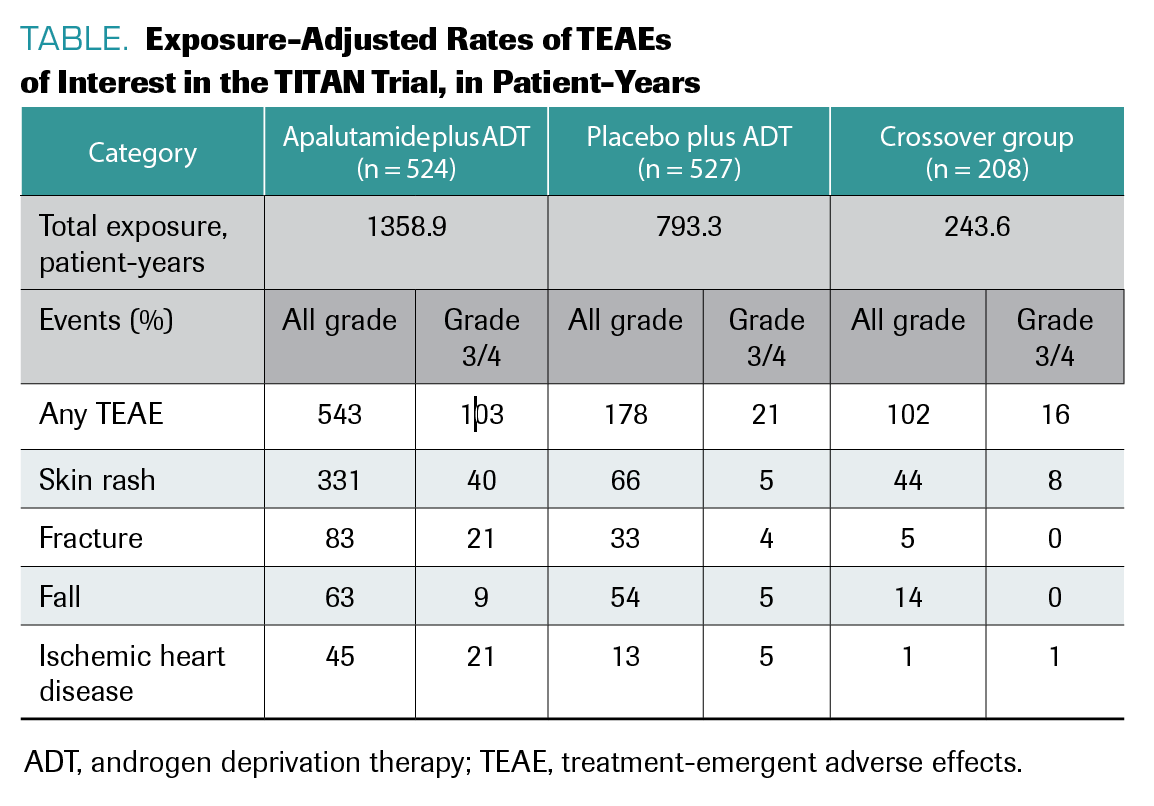

Chowdhury explained that toxicities were manageable for patients receiving apalutamide, with rash as the most common treatment-emergent adverse effect (TEAE) in both arms (TABLE). Agarwal said quality of life was top of mind for him in this research and explained the importance of this variable for providers and patients with mCSPC alike.

TABLE. Exposure-Adjusted Rates of TEAEs of Interest in the TITAN Trial, in Patient-Years

“Quality of life is very dear to all of our patients and us as providers,” he explained. “Anytime we discuss treatment with our patients, the number one concern in my patient’s mind is how it is going to impact their quality of life.”

The study evaluated quality of life via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) questionnaire. The analysis did not find any deterioration of quality of life as reported by patients treated with apalutamide. Simply put, Agarwal said, “apalutamide improved survival without compromising quality of life.”

Chowdhury further emphasized the importance of quality of life, and said, “we [as providers] underestimate every blood test, every scan, and every clinic visit.”

But with the promise seen with apalutamide plus ADT for patients, Chowdhury sees potential in a better treatment experience and expressed how important that will be for patients.

“One of the things about treatments that are active is that you have to monitor them because there are subtleties and you can miss the nuance. But because of the excellent PSA control, we can [tell patients] to come back in 3 months’ time, and they’ll walk out a couple inches taller.”

Forward-Looking Ideas

Both Agarwal and Chowdhury agree that the combination treatment with an androgen signaling inhibitor plus ADT is preferred and more effective than

ADT alone.

“With data like this, you’d be in a difficult position to argue why you’ve just given ADT alone,” Chowdhury remarked. “It’s a strange thing in medicine that, because ADT works, we don’t implement the change quickly enough. I appreciate that change is difficult, but this is different. This is a real step-change improvement.”

“Apalutamide in this paper improves overall survival in a clinically meaningful fashion without compromising quality of life for patients.,” Agarwal explained.

References

- Agarwal N, Mundle S, Dearden L, et al. Use and outcomes in men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) treated with docetaxel in addition to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT): Analysis of real-world data in the United States (US). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl 15):e19322. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e19322

- Ke X, Lafeuille M-H, Romdhani H, et al. Treatment patterns in men with metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) in the United States (US). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl 15):e19131. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e19131

- Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(20):2294-2303. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.03488

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(1):13-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903307

EP: 1.Apalutamide in Patients with mCSPC: Background

EP: 2.Apalutamide in Patients With mCSPC: Survival

EP: 3.The TITAN Study: Secondary End Points

EP: 4.Apalutamide in Patients With mCSPC: Safety

EP: 5.Key Takeaways for Use of Apalutamide With Androgen Deprivation Therapy

EP: 6.Future Directions and Novel Combination Therapies for mCSPC

EP: 7.The Role of Apalutamide in Patients With Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Prolaris in Practice: Guiding ADT Benefits, Clinical Application, and Expert Insights From ACRO 2025

April 15th 2025Steven E. Finkelstein, MD, DABR, FACRO discuses how Prolaris distinguishes itself from other genomic biomarker platforms by providing uniquely actionable clinical information that quantifies the absolute benefit of androgen deprivation therapy when added to radiation therapy, offering clinicians a more precise tool for personalizing prostate cancer treatment strategies.