3 Things You Should Know About Identifying and Treating Epithelioid Sarcoma

Experts discuss epithelioid sarcoma diagnosis, management, and targeted therapies, and highlight 3 things everyone should know about treatment.

The experts

RELEASE DATE: February 1, 2025

EXPIRATION DATE: February 1, 2026

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon successful completion of this activity, you should be better prepared to:

- Differentiate epithelioid sarcoma from other malignant and nonmalignant lesions by identifying key characteristics and the clinical presentation

- Implement a multidisciplinary management approach for epithelioid sarcoma including the roles of surgical oncology, pathology, radiation therapy, and medical oncology to optimize patient outcomes through coordinated care and individualized treatment planning.

Accreditation/Credit Designation

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Acknowledgment of commercial support

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc.

Off-label disclosure/disclaimer

This activity may or may not discuss investigational, unapproved, or off-label use of drugs. Learners are advised to consult prescribing information for any products discussed. The information provided in this activity is for accredited continuing education purposes only and is not meant to substitute for the independent clinical judgment of a health care professional relative to diagnostic, treatment, or management options for a specific patient’s medical condition. The opinions expressed in the content are solely those of the individual faculty members, and do not reflect those of PER® or any company that provided commercial support for this activity.

Instructions for participation/how to receive credit

- Read this activity in its entirety.

- Go to https://www.gotoper.com/cac25es-postref to access and complete the posttest.

- Answer the evaluation questions.

- Request credit using the drop-down menu.

YOU MAY IMMEDIATELY DOWNLOAD YOUR CERTIFICATE.

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare form of soft tissue sarcoma (STS) that accounts for fewer than 1% of STS cases.1 The disease is known for being difficult to diagnose and treat and for being associated with high rates of local recurrence (34%-77%) and metastasis (≈40%).2 As such, it is important to have up-to-date and accurate information about ES. Here are 3 things you should know about identifying and treating ES.

1. ES is often misdiagnosed, but it has distinctive features that can aid in identification.

The incidence of ES in the United States is approximately 5 cases per million individuals.3 Classic, or distal-type, ES usually presents as a painless, flesh-colored mass on the distal aspect of an extremity and sometimes with overlying ulceration, bleeding, or necrosis.1,2 Proximal-type ES also appears as a painless lesion, but it can be located on the proximal extremity, trunk, or pelvis.4 Thus, ES shares many presenting features with various soft tissue lesions, benign or malignant. It is therefore not surprising that it is often initially misdiagnosed.5

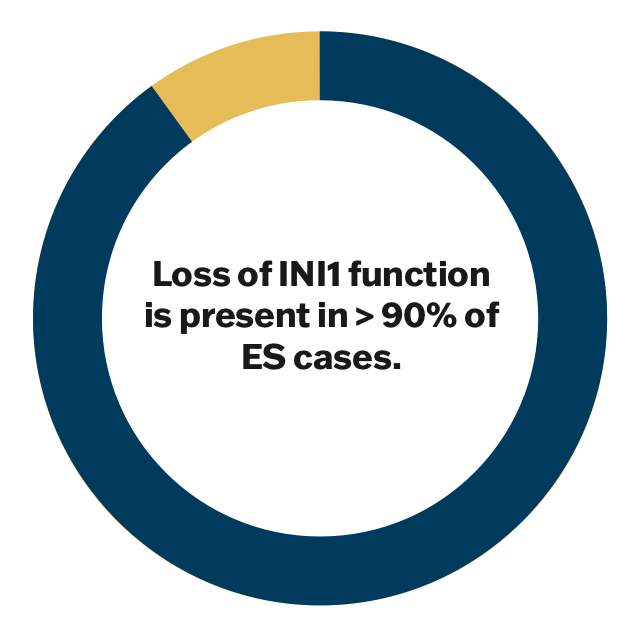

Given the ambiguous clinical features of ES, the diagnosis often hinges on microscopic appearance and genetic analysis. The distinctive mutation in ES is a loss of INI1 function, which is present in over 90% of tumors regardless of subtype.6 Other molecular features of ES include the presence of vimentin, cytokeratin, and epithelial membrane antigen, although these are nonspecific markers.

As with all suspected cases of STS, it is recommended that possible ES lesions be evaluated by collaborating members of a multidisciplinary team who are experienced in the management of sarcomas.7 Such a team will often include a medical oncologist, orthopedic surgeon, pathologist, radiation oncologist, and other supporting health care providers. A team approach helps to ensure that the diagnosis and treatment plan are both timely and accurate.

Figure 1

2. ES treatment follows guidelines, but it is individualized based on disease characteristics.

As with many other types of cancer, treatment for ES follows some general evidence-based guidelines. However, the treatment plan is developed individually by a multidisciplinary team and influenced by aspects of the disease and patient factors.

Wide surgical excision of the tumor with neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiation treatment of the tumor bed is the primary treatment of choice in most cases of ES.2,7,8 Depending on the location and extent of local tumor invasion, limb-sparing surgery may or may not be feasible, with amputation being the alternative.7,8 Perioperative radiation treatment effectively reduces rates of local recurrence, and it is recommended in all but the lowest stages of ES.7,8

Disease that recurs, metastasizes, or is diagnosed at an advanced stage is often treated with some form of systemic therapy (eg, traditional chemotherapy or targeted medication).7 In addition to disease factors, individual patient characteristics must be considered, and shared decision-making is encouraged. Age, comorbidities, personal goals, and lifestyle factors all have the potential to tip the scales of treatment decisions.

3. Systemic treatment for ES is reserved for advanced cases, but it has improved with the addition of targeted therapy.

The use of systemic treatment for STS has traditionally been controversial, and it is reserved for advanced cases.7,8 Indeed, NCCN guidelines only recommend systemic treatment when the primary tumor is unresectable, the disease is metastatic at diagnosis, or recurrence has occurred following primary treatment.7 The prognosis for patients who qualify for systemic treatment is generally poor, with a median life expectancy of 8 months for metastatic ES.2

Historically, systemic treatment for advanced cases of ES has not been particularly promising. Two retrospective, single-arm cohort studies on traditional chemotherapy (specifically, anthracycline, gemcitabine, and/or ifosfamide-based regimens) for the treatment of ES did not demonstrate favorable outcomes. The overall response rates in both studies were around 15%, and progression-free survival ranged from 43.3 to 66.3 weeks.9,10 Moreover, the results of 1 of these studies found that 50% of the patients experienced an adverse event during treatment.9

Mechanistic insight into the root cause of ES has led to the development of a promising targeted treatment, however. As mentioned above, over 90% of ES tumors demonstrate a loss of INI1 function.6 INI1 is a tumor suppressor that inhibits the EZH2 enzyme, indirectly stimulating the transcription of tumor suppressor genes.11 Tazemetostat is a novel EZH2 inhibitor that was developed to treat ES. In 2020, the medication received accelerated approval and orphan drug status from the FDA for treating advanced ES based on results of a phase 2 clinical trial.12 The study enrolled 62 patients; investigators found an objective response rate of 15%, with 26% of patients having disease control at 32 weeks of follow-up.12 This has led to NCCN guidelines listing tazemetostat as the preferred treatment for recurrent, metastatic, or locally advanced and unresectable ES.7 Additionally, tazemetostat is still being investigated in combination with doxorubicin as a first-line systemic therapy for advanced ES.13

Figure 2

Key References

1. Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-from genetics to clinical practice. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(8):2112. doi:10.3390/cancers12082112

7. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 4.2024. Accessed January 1, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1464

12. Gounder M, Schöffski P, Jones RL, et al. Tazemetostat in advanced epithelioid sarcoma with loss of INI1/SMARCB1: an international, open-label, phase 2 basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1423-1432. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30451-4

For full list of references, visit

https://www.gotoper.com/cac25es-postref

CME Posttest Questions

Claim Your CME Credit at https://www.gotoper.com/cac25es-postref

1. In the management of epithelioid sarcoma (ES), targeting EZH2 addresses which of the following features present in most cases leading to uncontrolled tumor growth?

A. Increased expression of INI1/SMARCB1 resulting in upregulation of EZH2

B. Increased expression of INI1/SMARCB1 resulting in downregulation of EZH2

C. Loss of INI1/SMARCB1 resulting in upregulation of EZH2

D. Loss INI1/SMARCB1 resulting in downregulation of EZH2

2. Your 21-year-old male patient is referred to you after an initial consult with an orthopedic surgeon who performed a core needle biopsy on a firm, nonmobile mass on his forearm that gradually increased in size over the past 18 months. MRI showed heterogeneous necrosis indicative of malignancy, but CT scans of the chest, abdomen, pelvis are negative for metastatic disease. Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor is positive for CD34, cytokeratin, EMA, and vimentin, and negative for CD31, S-100, and INI1, confirming the diagnosis of ES. According to current data and guideline recommendations, what is the next best step in the management of this patient’s ES at this time?

A. Doxorubicin

B. Gemcitabine plus docetaxel

C. Larotrectinib, 100 mg, orally twice daily

D. Tazemetostat, 800 mg, orally twice daily

E. Tazemetostat, 800 mg, orally twice daily plus doxorubicin

To learn more about this topic, including information on the identification, diagnosis, and management of epithelioid sarcoma, go to https://www.gotoper.com/cac25es-activity

CME Provider Contact information

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC

2 Commerce Drive, Suite 110, Cranbury, NJ 08512

Toll-Free: 888-949-0045

Local: 609-378-3701

Fax: 609-257-0705

info@gotoper.com

Sarcoma Awareness Month 2023 with Brian Van Tine, MD, PhD

August 1st 2023Brian Van Tine, MD, PhD, speaks about several agents and combination regimens that are currently under investigation in the sarcoma space, and potential next steps in research including immunotherapies and vaccine-based treatments.