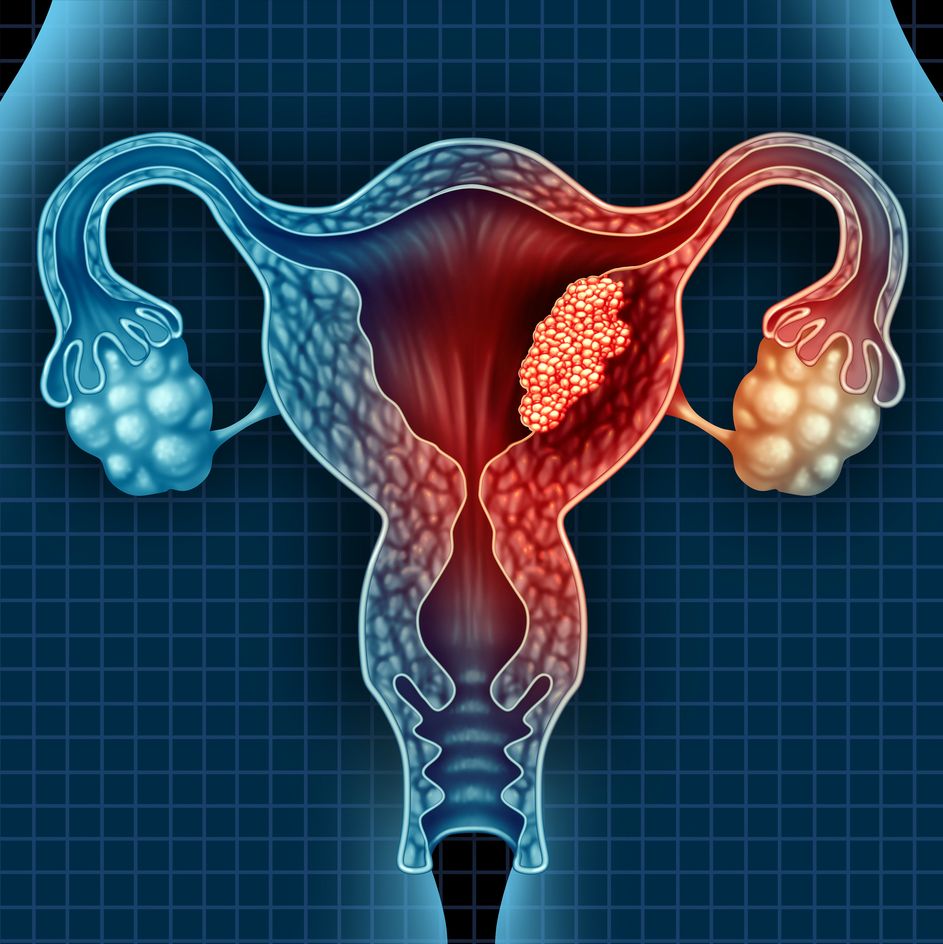

Atezolizumab Combo Displays Noninferior Survival in Endometrial Cancer

A significant survival improvement was observed among patients with dMMR carcinomas who received atezolizumab/chemotherapy.

12.1% of the atezolizumab arm vs 29.2% of the placebo arm received subsequent immunotherapy upon treatment discontinuation.

The addition of atezolizumab (Tecentriq) to chemotherapy demonstrated noninferior survival compared with placebo plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer, according to a presentation on the phase 3 AtTEnd/ENGOT-EN7 trial (NCT03603184) at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025.1

After a median follow-up of 48.9 months, the overall survival (OS) analysis displayed a nonsignificant difference among patients treated with atezolizumab vs placebo at a median of 36.0 months (95% CI, 30.0-45.2) vs 30.5 months (95% CI, 25.0-41.8), respectively. The respective 12- and 24-month OS rates were 80.1% vs 73.8% and 61.1% vs 58.4% (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.10; P = .0824). Additionally, 12.1% of the atezolizumab arm vs 29.2% of the placebo arm received subsequent immunotherapy upon treatment discontinuation.

Furthermore, in a planned subgroup analysis based on mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) status, those with dMMR disease experienced significantly improved OS outcomes with atezolizumab. After a median follow-up of 49.1 months, the median OS was not evaluable (95% CI, 60.9-NE) in the atezolizumab arm vs 31.8 months (95% CI, 13.5-47.0) in the placebo arm; the respective 12- and 24-month rates were 86.8% vs 66.8% and 74.8% vs 54.8% (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28-0.83; P = .0038). Additionally, 7.4% vs 45.5% of the respective arms received subsequent immunotherapy.

Among those with non-dMMR status, survival outcomes did not significantly differ between the 2 regimens. After a median follow-up of 49.6 months, the median OS was 30.0 months (95% CI, 23.8-37.4) with atezolizumab vs 30.2 months (95% CI, 22.4-40.7) with placebo, and the 12- and 24-month rates were 77.8% vs 75.8% and 55.9% vs 58.8%, respectively (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.78-1.34; P = .6644). In the respective arms, 13.8% vs 24.3% received subsequent immunotherapy.

Additionally, among all comers, the progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes numerically favored atezolizumab. In the investigational and placebo arms, the median PFS was 9.9 months (95% CI, 9.3-12.0) vs 8.9 months (95% CI, 8.1-9.6), with respective 12- and 24-month rates of 44.7% vs 28.9% and 28.7% vs 16.8% (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.86; P = .0055). Moreover, a non-proportional hazards restricted mean survival time difference of 2.52 months (95% CI, 0.82-4.22) at 30 months was observed.

Among patients with dMMR disease, atezolizumab exhibited enhanced PFS outcomes vs placebo. With the respective regimens, the median PFS was not evaluable (95% CI, 12.3-NE) vs 6.9 months (95% CI, 6.2-9.0); and the respective 12- and 24-month PFS rates were 62.7% vs 23.3% and 52.1% vs 16.3% (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.22-0.55; P = .0002).

For those with non-dMMR status, noninferior PFS was observed with atezolizumab. The median PFS was 9.5 months (95% CI, 9.0-10.4) with atezolizumab vs 9.2 months (95% CI, 8.5-9.9) with placebo. The PFS rates were 39.1% vs 30.2% at 12 months and 21.7% vs 16.0% at 24 months in each respective arm (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.69-1.08; P = .1885).

Furthermore, the objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) among patients with dMMR status numerically favored the atezolizumab arm. The ORR with atezolizumab was 82.4% (95% CI, 71.4% vs 89.7%) with a complete response (CR) rate of 26.5% and a partial response (PR) rate of 55.9%; with placebo, the ORR was 75.7% (95% CI, 56.3%-84.7%), with a CR rate of 18.9% and a PR rate of 56.8%. Regarding DOR, the median values were not evaluable (95% CI, 15.0-NE) with atezolizumab vs 4.9 months (95% CI, 4.3-8.4) with placebo; the 12- and 24-month rates were 66.9% vs 22.3% and 57.6% vs 14.8% (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.15-0.47).

In the non-dMMR population, noninferior ORR and DOR outcomes with atezolizumab were observed. With atezolizumab, the ORR was 75.6% (95% CI, 65.3%-77.0%) with CR and PR rates of 15.1% and 60.5% vs an ORR of 74.6% (95% CI, 61.9%-78.1%) with CR and PR rates of 10.5% and 64.0% with placebo. The median DOR in the respective arms was 7.8 months (95% CI, 6.9-9.7) vs 7.0 months (95% CI, 5.6-7.9), with 12- and 24-month rates of 35.1% vs 29.8% and 19.9% vs 15.0% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.61-1.07).

“The addition of atezolizumab to chemotherapy did not demonstrate a statistically significant survival benefit in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma,” Maria Pilar Barretina Ginesta, MD, associate professor of the Medical Sciences Department of Girona University and assistant chief of the Medical Oncology Department at the Institut Catala D Oncologia in Girona, Spain, said in the presentation. “In the pre-planned subgroup analysis based on MMR status, a substantial survival improvement was observed in patients with dMMR carcinomas.”

The phase 3 study enrolled patients with advanced newly diagnosed or recurrent endometrial carcinoma or carcinosarcoma and randomly assigned them 2:1 to receive paclitaxel at 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin area under the curve 5 or 6 with 1200 mg of atezolizumab or matching placebo. Following chemotherapy, patients received 1200 mg of atezolizumab as maintenance or matching placebo. Those eligible for enrollment also had an ECOG performance status of 0 to 2 and normal organ and bone marrow function. Those with recurrent disease were permitted to have 1 prior line of systemic platinum-based chemotherapy with a platinum-free interval of less than 6 months.

Those enrolled were stratified by country, histology, recurrent status, and dMMR status. The dual primary end points of the study were PFS and OS.

Among all comers in the atezolizumab (n = 360) and placebo arms (n = 189), 22.5% vs 23.3% had dMMR status. Furthermore, 67.5% vs 66.7% had recurrent disease status, and 70.6% vs 68.2% did not receive previous chemotherapy. Among patients with newly diagnosed disease in the respective arms, 75.2% vs 85.7% had measurable disease. The median age was 67 years (range, 30-89) vs 65 years (range, 30-89), and most patients were Caucasian (80.3% vs 75.7%), had PD-L1–negative disease (68.6% vs 68.2%), and had intact ARID1A expression (68.9% vs 69.3%).

Any-grade adverse effects (AEs) occurred in 98.6% vs 100% of patients in the atezolizumab and placebo arms, respectively; those related to atezolizumab vs placebo occurred in 75.8% vs 63.8%. Grade 3 or higher AEs were observed in 26.4% vs 14.1% of the respective arms, and fatal AEs related to either agent occurred in 0.3% vs 0.5% of patients.

The most common AEs in the atezolizumab and placebo arms were anemia (41.3% vs 35.1%), fatigue (39.0% vs 41.1%), neutropenia (40.7% vs 39.5%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (38.8% vs 39.5%), nausea (34.0% vs 37.3%), and alopecia (31.5% vs 36.2%).

Reference

Ginesta MP, Biagioli E, Harano K, et al. Final overall survival (OS) results from the randomized double-blind phase III AtTEnd/ENGOT-EN7 trial evaluating atezolizumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in women with advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer. Presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025; October 17-21, 2025; Berlin, Germany. Abstract LBA39.

Gedatolisib Combo With/Without Palbociclib May Be New SOC in PIK3CA Wild-Type Breast Cancer

December 21st 2025“VIKTORIA-1 is the first study to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS with PAM inhibition in patients with PIK3CA wild-type disease, all of whom received prior CDK4/6 inhibition,” said Barbara Pistilli, MD.