Biology and Management of Rare Primary Extranodal T-cell Lymphomas

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are uncommonly encountered malignancies in the United States, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL), subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL), and enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTCL) are rare subtypes of PTCLs that often present with primarily extranodal disease. Despite the fact that these tumors have distinct clinical and pathologic features, they are often diagnosed after significant delay. The combination of delay in diagnosis with ineffective therapies has resulted in a poor prognosis in most cases. Techniques that identify T-cell receptor gene rearrangements and flow cytometry that can identify characteristic immunophenotypes have guided our understanding of the underlying cell of origin of these rare PTCLs. As knowledge regarding the biology of these lymphomas increases alongside the development of newer therapeutics with novel mechanisms, clinicians must accordingly improve their familiarity with the clinical settings in which these rare malignancies arise as well as the pathologic features that make them unique

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are uncommonly encountered malignancies in the United States, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL), subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL), and enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTCL) are rare subtypes of PTCLs that often present with primarily extranodal disease. Despite the fact that these tumors have distinct clinical and pathologic features, they are often diagnosed after significant delay. The combination of delay in diagnosis with ineffective therapies has resulted in a poor prognosis in most cases. Techniques that identify T-cell receptor gene rearrangements and flow cytometry that can identify characteristic immunophenotypes have guided our understanding of the underlying cell of origin of these rare PTCLs. As knowledge regarding the biology of these lymphomas increases alongside the development of newer therapeutics with novel mechanisms, clinicians must accordingly improve their familiarity with the clinical settings in which these rare malignancies arise as well as the pathologic features that make them unique.

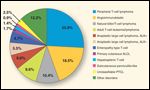

FIGURE 1

Distribution of PTCL Cases

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are uncommonly encountered malignancies that comprise only 5% to 10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States.[1] Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL), subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL), and enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTCL) are rare subtypes that frequently present without any nodal involvement and make up only about 10% of all PTCLs with relative frequencies shown in Figure 1. Therefore, they can easily be misdiagnosed without proper clinical suspicion and familiarity with the clinical settings in which they arise.

PTCLs are malignancies of an immunologically mature T cell that has migrated from its site of differentiation in the thymus to a peripheral site of lymphoid tissue. In thymic development, immature thymocytes undergo sequential rearrangement of their TCR genes. Normal mature T cells express two mutually exclusive types of CD3-associated T-cell receptor heterodimers: the α/β T-cell heterodimer and the γ/δ T-cell heterodimer. It is now recognized that the majority of PTCLs arise from α/β T cells with only a minor subset that arise from cells expressing the γ/δ T-cell receptor.[2] γ/δ T cells, along with natural killer (NK) cells, are part of the innate immune system and exhibit preferential homing to the mucosa of the skin, the intestinal epithelium, and the sinusoidal areas of the spleen. Notably, it is these sites that are commonly affected by γ/δ T-cell lymphomas.[3]

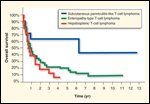

FIGURE 2

Overall Survival in PTCL Patients

Primary extranodal PTCLs have disappointing outcomes when treated with conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens regardless of traditional prognostic variables such as those included in the International Prognostic Index (IPI).[1,4] The combination of frequent delays in diagnosis with the therapy-refractory nature of these tumors has led to a historically poor prognosis, as demonstrated in Figure 2. However, since these primary extranodal PTCLs have very distinctive clinical and pathologic presentations, improved understanding and recognition may lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier institution of proper therapy. Without improvements in recognition, however, the improved biologic understanding of these diseases and improved novel therapies will not lead to an overall improvement in outcomes.

Hepatosplenic T-cell Lymphoma

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) was first accurately described in 1990 by Farcet et al in two young adult males who presented with systemic symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and an absence of lymphadenopathy.[5] Both patients achieved complete remissions to their initial therapy but quickly relapsed and subsequently died of their disease. Subsequent case reports confirmed it as a distinct clinicopathologic entity, and it was first provisionally recognized as a distinct lymphoma entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification in 1994.[6-11] In the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification, both the γ/δ-type as well as the α/β-type are included under the term hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, although epidemiologic and biologic differences may exist.[12]

HSTCL is a very rare form of PTCL as it represents only 1.4% of cases of peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas worldwide. Regionally, it represents a slightly higher percentage of all PTCLs in North America (3.0%) and Europe (2.3%) but is vanishingly rare in Asia (0.2%). Median age at time of diagnosis is 34 years, and 68% of cases are in male patients.[1]

The classic clinical presentation of HSTCL is a young male who presents with systemic symptoms, jaundice, abdominal pain, significant thrombocytopenia with or without anemia, and marked hepatosplenomegaly without associated lymphadenopathy. Involvement of the peripheral blood with circulating lymphocytes, erythrophagocytosis, and involved lymph nodes are not common features early in the disease but may occur in late stages of illness. Bone marrow involvement is an almost constant feature. Often there is evidence of diffuse hepatic enlargement in the absence of gross lesions.[6-11]

Approximately 10% to 20% of HSTCL patients have a history of immunocompromise, including solid organ transplantation, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus, Hodgkin lymphoma, and malarial infection.[9,13,14] All of these conditions are known to be associated with the expansion of γ/δ T cells as a result of chronic antigen stimulation, but there is no known association with viral infection and almost every described case is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative. It has been described as a late complication posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder occurring up to 10 years after transplantation.[13,14]

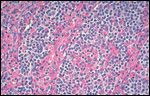

FIGURE 3

Sinusoidal Infiltration of Spleen in Hepatosplenic T-cell Lymphoma

Without an experienced hematopathologist, the diagnosis of HSTCL can be missed, and interobserver agreement on diagnosis from expert hematopathologists in the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project was only 72%.[1] Normally, lymphomas invade the portal tracts of the liver and are seen mainly in the white pulp of the spleen. HSTCL, in contrast, is characterized by marked sinusoidal infiltration of spleen with resultant atrophy of the white pulp (Figure 3). Liver involvement is characterized by marked sinusoid expansion and sparing of the portal triads without hepatocyte destruction.[5-11] Morphologically, small clusters of a monomorphic population of medium-sized lymphoid cells are typically seen, with moderately clumped chromatin and a rime of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.[3]

FIGURE 4

Immunohistochemical Stain of Hepatosplenic T-cell Lymphoma

The bone marrow is characteristically hypercellular and the diagnosis is greatly facilitated by use of proper immunohistochemical stains, since the lymphoma cells may be difficult to identify with light microscopy alone (Figure 4). The neoplastic cells have a phenotype resembling immature cytotoxic T cells and are typically CD2+, CD3+, CD4–, CD5–, CD7+, CD8–, with either TCR-γ/δ+ o r TCR-α/β+.[3, 7-9] Many variations exist, however, and some cases may be CD8+. Other antigens that are frequently positive are NK-related antigens such as CD16 and CD56.[7-9]

The neoplastic cells have rearranged TCR genes, and the diagnosis of HSTCL occasionally may rely solely on T-cell receptor rearrangement. Unfortunately, there are no available monoclonal antibodies against the γ/δ T-cell receptor for use with paraffin-embedded tissue. The majority of cases of HSTCL are of the γ/δ-type, but cases that express the α/β-type receptor are considered immunophenotypic variants of the same disease.[10,11]

HSTCL is associated with recurrent cytogenetic chromosomal abnormalities such as isochromosome 7q translocations, which frequently occur in association with trisomy 8.[7,8,11-15] Cases of trisomy 8 without isochromosome 7q translocations, however, have not been reported. Available data from gene-expression profiling also supports the notion that hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is a distinct entity as it has a characteristic signature that is distinct from other PTCLs.[16]

HSTCL has the worst prognosis of all PTCLs, with 5-year failure-free survival and overall survival rates of 0% and 7%, respectively.[1] There is no reliable biomarker to predict prognosis, and the IPI score is not helpful in risk stratification. Since this disease was first reported in the early 1990s, most patients reported have survived less than 1 year despite aggressive combinations of chemotherapy.[6-13]

Reduction of immunosuppression is ineffective for HSTCLs that arise in the posttransplant setting, and all cases should be treated with chemotherapy at diagnosis. Although most patients are refractory to anthracycline-based therapy or have only brief responses, limited evidence suggests that some patients may respond to a platinum/cytarabine-based induction regimen.[8] All patients remain at significant risk of relapse, as the durations of response are very short. Consolidation with allogeneic stem cell transplantation should be offered to all eligible patients since there has been a demonstrable graft-vs-lymphoma effect and it is likely that stem cell transplantation from an allogeneic donor offers the only chance for durable remission in this disease.[17-20]

Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma

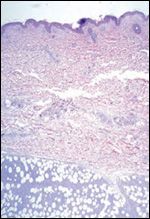

FIGURE 5

Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a very rare primary extranodal T-cell lymphoma in which the malignant cells preferentially infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 5). It was first accurately described in 1991 by Gonzalez et al, who presented eight cases involving patients presenting with multiple subcutaneous nodules mimicking benign lobular panniculitis.[21] It was first provisionally recognized as a distinct lymphoma entity by the REAL classification in 1994 and is currently recognized in the WHO classification as a distinct clinicopathologic entity regardless of the TCR subtype.[22] Increasing evidence suggests that the γ/δ-subtype of SPTCL is a more aggressive variant and should be separated out as a distinct entity named cutaneous γ/δ-T-cell lymphoma.[4,23-24]

SPTCL is the rarest of all PTCLs and represents only 0.9% of PTCLs worldwide.[1] It occurs in a very broad range of ages, with the median age at time of diagnosis being 33 years old but with cases reported in patients less than 2 years old. It has historically been described as occurring in males and females equally, but in the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project, 75% of cases occurred in males.[1]

SPTCL usually presents with symptoms related to multiple subcutaneous nodules, typically involving the extremities, the trunk, and occasionally the face; usually in the absence of extracutaneous sites of disease. The nodules can vary in size, with larger nodules often ulcerating, and may become necrotic. Many patients have systemic symptoms of fever, malaise, myalgias, chills, and weight loss as well as clinical signs of pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly at the time of diagnosis.[25,26] The pancytopenia likely represents a cytokine-induced bone marrow suppression, since only 8% have direct bone marrow involvement.[1] Hemophagocytic syndrome is a frequent and significant complication of SPTCL and is a presenting feature in one-third of patients.[3] For those without systemic symptoms at diagnosis, the development of hemophagocytosis can precipitate a fulminant downhill clinical course and is the commonest cause of clinical decline, as systemic dissemination of lymphoma is rare.[21,25,26]

SPTCL can be a diagnostic challenge, and the clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion as it often looks deceptively like benign lobular panniculitis due to paucity of inflammatory cells. Histologically, it is characterized by a pleomorphic admixture of lymphocytes of varying size, often with marked fat necrosis and karyorrhexis. Reactive benign histiocytes are often admixed in areas of fat infiltration of tumor cells.[25,26] The neoplastic cells generally are confined to the subcutaneous tissue without dermal and epidermal involvement. They frequently infiltrate individual fat cells with a rim-like arrangement at the cell border, which may be a feature that helps to distinguish this entity.[3]

The neoplastic cells have a mature cytotoxic T-cell phenotype, and immunophenotypic studies typically reveal the loss of a pan T-cell antigen such as CD5 or CD7. The cells are typically CD3+, CD4–, and CD8+, with either TCR-α/β+ or TCR-γ/δ+.[21-25] Diagnosis may rely on the demonstration of T-cell receptor rearrangement; it is usually the α/β-type, but up to 25% of cases may be the γ/δ-type.[25-26] Tumors that are “double-negative” for CD4 and CD8 as well as those that express CD16 almost exclusively express the γ/δ-TCR. All cases of SPTCL are EBV-negative.

SPTCL seems to follow one of two clinical courses. Most cases are clinically aggressive, especially those involving the γ/δ-subtype and those positive for the NK-associated antigen CD 56. Some patients, however, with the α/β-subtype and CD56– have a more indolent disease course before developing systemic complications.[21-26] Clinical features that identify patients who may have an indolent disease course require further clarification.

At the present time, there is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment of SPTCL. Radiation therapy is often effective for localized disease. Patients with more aggressive disease may respond initially to anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy, and ~30% will achieve long-term remissions.[26] The 5-year failure-free and overall survival rates, however, were only 24% and 64% in the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project, due to the propensity for the disease to relapse.[1] Subcutaneous recurrences are common and typically do not affect survival, but the presence of the hemophagocytic syndrome is a common cause of clinical deterioration. The use of high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation may be a successful salvage strategy for recurrent disease, since 12 of 13 patients achieved a complete remission in one review.[26]

Enteropathy-type T-cell Lymphoma

Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTCL) is a rare primary extranodal T-cell lymphoma in which the malignant cells invade the intestinal wall epithelium, often in the context of a history of celiac disease. It is also known as intestinal T-cell lymphoma and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, which was a term first coined by O’Farrelly et al in 1986.[27] ETTCL is currently recognized in the WHO classification as a distinct clinicopathologic entity, but available evidence suggests that there are two histologic subgroups with unique clinical and immunophenotypic features: a pleomorphic anaplastic type and a monomorphic type.[28]

ETTCL is a rare neoplasm that represents only 4.7% of the cases of peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas worldwide. It is more common in geographic regions of the world with a higher incidence of celiac disease, as evidenced by the fact that it represents 5.8% and 9.1% of the PTCLs in North America and Europe but only 1.9% of those in Asia. The median age at time of diagnosis is 61 years old with only a slight male predominance, in contradistinction to the striking male predominance reported in early case series.[1]

The most common presenting symptoms of ETTCL are abdominal pain, malabsorption, weight loss, and a protein-losing enteropathy. It arises in the setting of long-standing celiac disease in only a minority of patients, and usually there is only a short history of malabsorption or even no clear history of malabsorptive symptoms. Nonetheless, in patients with known celiac disease who have become unresponsive to a gluten-free diet, there is an increase in the incidence of lymphoma as well as populations of clonal intraepithelial T cells.[29-34]

Involved organs are almost exclusively gastrointestinal, with the proximal jejunum being the most common, but ETTCL may also invade the stomach, colon, or other parts of the small intestine. Up to 40% of patients ultimately diagnosed with ETTCL seek medical care with an acute abdomen, owing to either a small bowel perforation or obstruction with associated peritonitis.[29-34] In the majority of cases, the lesions are seen as nodules, plaques, strictures, or ulcerations without a definitive mass, and the diagnosis is often made at laparotomy.[34]

Lymphadenopathy is not a presenting feature of ETTCL, and the bone marrow is involved in only 3% of patients.[1] Laboratory abnormalities are relatively stark, with only a mild anemia seen in two-thirds of cases and the frequent occurrence of normal levels of lactate dehydrogenase. The disease is metastatic to regional lymph nodes in one-third of cases, with spread to distant sites in only about 20% of cases.[34]

ETTCL must be distinguished from other lymphomas that present with intestinal disease, as not all intestinal lymphomas are ETTCL. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma can be distinguished based on EBV positivity, and most other cases of lymphoma involving the intestine are comprised of B cells. With the use of clinical data, the interobserver agreement between expert hematopathologists in the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project was 79% for ETTCL.[1]

FIGURE 6

Enteropathy-type T-cell LymphomaFIGURE 7

Enteropathy-type T-cell Lymphoma

Macroscopically, ETTCL forms multifocal circumferential ulcers in the bowel wall, and uninvolved adjacent mucosa usually demonstrates villous atrophy and increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes that are CD3+ and CD8+.[30] There are two histologic subsets of ETTCL: One is characterized by highly pleomorphic-anaplastic cells and one is more monomorphic (Figures 6 and 7). The pleomorphic variant is more likely to be associated with a history of celiac disease and is usually CD56–.[34] The monomorphic variant, however, is usually not associated with celiac disease and is commonly CD56+. Often, there is significant infiltration of inflammatory cells such as histiocytes and eosinophils within the specimen that may mask the neoplastic population. In fact, historic cases in the literature that were probably ETTCL were described as “malignant histiocytosis of the intestine.”

The neoplastic cells are mature cytotoxic T cells that express the TIA-1 antigen, have the immunophenotype of CD3+/CD7+/CD4–/CD8–, and express the homing receptor CD103.[29-32,34] CD8 may be positive in a subset of cases, and in most cases, a proportion of the tumor cells are strongly positive for CD30. All of the TCRs are the α/β-type, and EBV is negative in most cases.

ETTCL is associated with recurrent chromosomal imbalances, and by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), gains at chromosome 9q33-q34 can be found in up to 70% of cases.[33] Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probes for chromosome 9q may ultimately prove to be a useful molecular diagnostic tool but have yet to be tested in large series of patients.

The clinical course of ETTCL is highly aggressive, and even patients in low-risk IPI groups have poor outcomes with a high incidence of intestinal recurrences.[32,34] Despite the fact that the tumors are often initially responsive to chemotherapy, the 5-year failure-free and overall survival rates are 4% and 20%.[1] Patients with ETTCL are often not ideal candidates for aggressive chemotherapy owing to their poor nutritional state and the common situation of recovering from exploratory laparotomy. Thus, the overall poor prognosis likely reflects the combination of delays in diagnosis, poor performance status of the patient, and biologic aggressivity of the tumor.

Resection is the best initial management when possible, followed by combination chemotherapy in all patients. Enteral and parenteral nutritional support should be offered to all patients prior to systemic therapy in an effort to optimize their performance status. Initial responses to conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy are common, but relapses are frequent, with most patients dying from progressive disease.[32,34] Strong consideration should be given to consolidation with allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission in all eligible patients, since there are no proven effective strategies in the salvage setting.

Current Approach to Rare Primary Extranodal PTCLs

Rare primary extranodal PTCLs such as hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, and enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma present significant challenges to the clinician in terms of both diagnosis and management. All suspected cases of these entities should be reviewed by an expert hematopathologist who is familiar with their distinctive clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features in order to ensure accurate diagnosis.

After diagnosis is confirmed, each case requires an individualized approach at an institution with experience at managing these complex diseases since there is no uniformly accepted standard for first-line therapy that results in acceptable outcomes. It is well established that these disorders do not respond to anthracycline-based chemotherapy alone as well as their B-cell counterparts do. New agents with novel mechanisms such as histone deacetylase inhibitors, the newly US Food and Drug Administration–approved pralatrexate (Folotyn), and many forms of immunotherapy are rapidly changing the landscape for the treatment of all PTCLs.[35,36]

At every opportunity, patients with these rare conditions should be offered innovative treatment approaches with novel agents, preferably in the context of a carefully conducted clinical trial. In patients who do achieve remissions with initial therapy, strong consideration should be given to consolidation with allogeneic stem cell transplantation, especially for HSTCL, the γ/δ-subtype of SPTCL, and the anaplastic variant of ETTCL, given the dismal prognosis.

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article. This is a work of the US Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States.

References:

References

1. Vose JM, Armitage JO, Weisenburger D: International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: Pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol 26:4124-4130, 2008.

2. Macon WR: Peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 23:829-842, 2009.

3. Jaffe ES: Pathobiology of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 317-322, 2006.

4. O’Leary H, Savage KJ: The spectrum of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Curr Opin Hematol 16:292-298, 2009.

5. Farcet JP, Gaulard P, Marolleau JP, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: Sinusal/sinusoidal localization of malignant cells expressing the T-cell receptor. Blood 75:2213-2219, 1990.

6. Cooke CB, Krenacs L, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: A distinct clinicopathologic entity of cytotoxic T-cell origin. Blood 88:4265-4274, 1993.

7. Weidmann E: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. A review on 45 cases since the first report describing the disease as a distinct lymphoma entity in 1990. Leukemia 14:991-997, 2000.

8. Belhadj K, Reyes F, Farcet JP, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is a rare clinicopathologic entity with poor outcome: Report on a series of 21 patients. Blood 102:4261-4269, 2003.

9. Falchook GS, Vega F, Dang NH, et al: Hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma: Clinicopathological features and treatment. Ann Oncol 20:1080-1085, 2009.

10. Suarez F, Wlodarska I, Rigal-Huguet F, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: An unusual case with clinical, histologic, and cytogenetic features of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 24:1027-1032, 2000.

11. Macon WR, Levy NB, Kurtin PJ, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas. A report of 14 cases and comparison with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 25:285-296, 2001.

12. Gaulard P, Jaffe ES, Krenacs L, et al: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, in Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al (eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoeitic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed, pp 292-293. Lyon, France; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008.

13. Wu H, Mariusz AW, Przybylski G, et al: Hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma as a late-onset posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in renal transplant recipients. Am J Clin Pathol 113:487-496, 2000.

14. Khan WA, Yu L, Eisenbery AB, et al: Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma in immunocomprised patients. Am J Clin Pathol 116:41-50, 2001.

15. Alonsozana ELC, Stamberg J, Kumar D, et al: Isochromosome 7q: the primary cytogenetic abnormality in hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 11:1367-1393, 1997.

16. Miyazaki K, Yamaguchi M, Imai H, et al: Gene expression profiling of peripheral T-cell lymphomas including T-cell lymphoma. Blood 113:1071-1074, 2009.

17. Le Gouill S, Milpied N, Buzyn A, et al: Graft-versus-lymphoma effect for aggressive T-cell lymphomas in adults: A study by the Société Française de Greffe de Moëlle et de Thérapie Cellulaire. J Clin Oncol 26:2264-2271, 2008.

18. Domm JA, Thompson MA, Kuttesch JF, et al: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chemotherapy-refractory hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 27:607-610, 2005.

19. Mansour MR, Dogan A, Morris EC, et al: Allogeneic transplantation for hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant 35:931-934, 2005.

20. Konuma T, Ooi J, Takahashi S, et al: Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 48:630-632, 2007.

21. Gonzalez CL, Medeiros LJ, Braziel RM, et al: T-cell lymphoma involving subcutaneous tissue. Am J Surg Pathol 15:17-27, 1991.

22. Jaffe ES, Gaulard P, Ralfkiaer E, et al: Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, in Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al (eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoeitic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed, pp 294-295. Lyon, France; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008.

23. Slater DN: The new World Health Organization-European Organization for research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: A practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol 153:874-880, 2005.

24. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al: Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Definition, classification, and prognostic factors: An EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood 111:838-845, 2008.

25. Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, et al: Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol 22:881-893, 1998.

26. Go RS, Wester SM: Immunophenotypic and molecular features, clinical outcomes, treatments, and prognostic factors associated with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Cancer 101:1404-1413, 2004.

27. O’Farrelly C, Feighery C, O’Briain DS, et al: Humoral response to wheat protein in patients with celiac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma. Br Med J 293:908-910, 1986.

28. Isaacson PG, Chott A, Ott G, et al: Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, in Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al (eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoeitic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed, pp 289-291. Lyon, France; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008.

29. Gale J, Simmonds PD, Mead GM, et al: Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma: Clinical features and treatment of 31 patients in a single center. J Clin Oncol 18:795-803, 2000.

30. Bagdi E, Diss TC, Munson P, et al: Mucosal intra-epithelial lymphocytes in enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, ulcerative jejunitis, and refractory celiac disease constitute a neoplastic population. Blood 94:260-264, 1999.

31. Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, et al: Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Lancet 356:203-208, 2000.

32. Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, et al: Intestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on intestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 21:2740-2746, 2000.

33. Zettl A, Ott G, Makulik A, et al: Chromosomal gains at 9q characterize enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol 161:1635-1645, 2000.

34. Zettl A, deLeeuw R, Haralambieva E, et al: Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 127:701-706, 2007.

35. O’Connor OA, Horwitz S, Hamlin P, et al: Phase II-I-II study of two different doses and schedules of pralatrexate, a high-affinity substrate for the reduced folate carrier, in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoma reveals marked activity in T-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol 27:4357-4364, 2009.

36. Cheson BD: Novel therapies for peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Curr Opin Hematol 16:299-305, 2009.