Can We Know What to Do When DCIS Is Diagnosed?

It is ironic that while huge strides have been made in the treatment of invasive breast carcinoma, resulting in breast conservation for many women, the most appropriate treatment of noninvasive breast carcinoma remains a topic of hot debate.

Utilizing routine histopathologic parameters obtained from appropriately handled lumpectomy and mastectomy specimens, a rational therapeutic plan based on epidemiologic and outcome-based data can be devised for any patient diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). In order to make a sound decision when weighing the current treatment options for DCIS-which include excision alone, excision plus radiation, and mastectomy-the following are mandatory: 1) assurance of an accurate diagnosis, 2) assessment of DCIS size and grade, and 3) careful margin evaluation. Accurate grading of DCIS is critical, since high nuclear grade and the presence of necrosis are highly predictive of the inability to achieve adequate margins, of local recurrence, and of the probability of missed areas of invasion. Margin status is the single most important determinant of local control following breast conservation for DCIS; numerous studies have shown that as the margin width increases, the risk of local failure decreases. The pros and cons of irradiating conservatively treated patients with DCIS should be carefully weighed on a case-by-case basis. Despite the 20-year-old dogma that all patients treated with breast conservation should receive postoperative radiation, a subset of patients who can be successfully treated by excision alone has been identified.

It is ironic that while huge strides have been made in the treatment of invasive breast carcinoma, resulting in breast conservation for many women, the most appropriate treatment of noninvasive breast carcinoma remains a topic of hot debate. This article explores some of the issues related to this controversy, with an emphasis on critical therapy-guiding information that can be derived from appropriately handled specimens using routine histopathologic parameters.

The diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) was rare before the 1980s; however, DCIS now represents a significant proportion of breast cancers, with an estimated 54,010 new cases diagnosed in 2010. This markedly increased incidence is a reflection of the widespread use of high-quality mammography as well as the histologic recognition of a wide spectrum of disease. Before a definitive treatment plan can be devised for any patient diagnosed with DCIS, three things are mandatory: 1) assurance of an accurate diagnosis, 2) assessment of DCIS size and grade, and 3) careful margin evaluation. The information these provide should be considered when weighing the current therapeutic options for DCIS, which include excision alone, excision plus radiation, and mastectomy.

What is the most important entity in the differential diagnosis for DCIS?

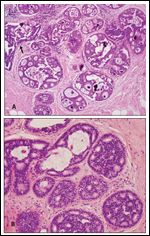

Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) is the most important entity included in the differential diagnosis for low-grade DCIS. ADH has histologic and molecular features that are similar to those of DCIS, but its natural history and therapeutic implications are quite different. ADH is associated with a bilateral increased risk of later cancer development (verified by several large epidemiologic studies) that is four to five times higher than that in age-matched controls.[1-4] This contrasts sharply with DCIS, a nonobligate local precursor for which subsequent risk is localized to the same breast and same site as the index DCIS.[5-7] Although establishing the diagnosis of DCIS is usually straightforward, distinguishing small, low-grade DCIS lesions from ADH can occasionally be difficult; however, this difficulty has recently been exaggerated.[8] In general practice, when strict epidemiologically validated criteria are followed, pathologists are able to accurately diagnose DCIS and can easily make this important distinction (Figure 1).[9] For the uncommon but clearly acknowledged borderline cases, a conservative diagnostic stance is favored to assure that the patient is not overtreated.

What is the natural history of DCIS?

Natural history studies from the premammographic era that retrospectively identified small, incidental, low-grade examples of DCIS clearly demonstrated that untreated DCIS carries a 25% to 30% absolute risk of recurrence localized to the same breast and same site as the index DCIS.[7,10] For low- and intermediate-grade DCIS, this risk may extend more than 20 years (although the greatest risk is in the first 10 years following biopsy). The interval of increased recurrence risk following a diagnosis of high-grade DCIS is significantly shorter.[11] Because under normal circumstances no woman today would go untreated when DCIS is diagnosed, these data do not apply directly. However, they can be used to make informed decisions regarding close or involved margins. Women with large DCIS lesions (greater than 5 cm) may not be candidates for breast conservation, since 10-year follow-up studies show that radiation cannot adequately compensate for close or involved margins[12] and may delay recurrence detection, resulting in a greater proportion of invasive recurrences than are seen with excision only.[13,14] In contrast, for small, completely excised DCIS, especially cases that are low grade and in older women, the recurrence interval may well extend beyond the life expectancy of the patient. Such lesions carry a low potential for subsequent invasive cancer development-approximately 1% per year.[15] This risk is only slightly greater than that associated with lobular carcinoma in situ, a lesion typically treated with close clinical follow-up. This wide spectrum of behavior underscores the important contributions made by studies that seek to identify a subset of low-risk patients who can be successfully treated by excision alone (see below). Indeed, Ozanne et al[16] have suggested, using statistical models, that the potential for DCIS to progress to invasive cancer is currently overestimated, often resulting in overtreatment.

How should an excisional biopsy specimen containing DCIS be handled?

FIGURE 1

Histologic Features for Differentiating Between Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) and Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH)

The majority of DCIS are now diagnosed by stereotactic core biopsy performed to evaluate mammographically detected microcalcifications. Establishing a diagnosis of DCIS on core biopsy allows for proper handling of a subsequent excisional biopsy specimen; proper handling is necessary in order that essential diagnostic elements not be compromised. Recent studies have shown that a systematic approach, including serial sectioning and sequential submission of lumpectomy specimens (which enables the extent of the DCIS to be measured in three dimensions), is a reliable and accurate method for documenting DCIS size.[17,18] The importance of the pathologist's careful attention to this measurement cannot be overemphasized, as it directly impacts further treatment considerations. DCIS size has been shown by numerous studies to correlate with close or positive margins, the likelihood of residual disease, and the probability of local recurrence and missed areas of invasion.[19-28] In addition, radiographs of the whole specimen should be obtained at the time of surgery-preferably in at least two dimensions-to document the presence of microcalcifications and their relationship to the surgical margins. This can facilitate removal of additional margins at the time of the initial surgery, thereby avoiding a second surgical procedure. Although not mandatory, obtaining additional radiographs of the sliced specimen can also be very useful in guiding the sampling of large specimens for which complete embedding is not feasible.

Which histologic characteristics have an impact on treatment?

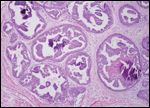

Specific histologic features can have a significant impact on the treatment plan. Accurate grading of DCIS is critical, since high nuclear grade and the presence of necrosis are highly predictive of the inability to achieve adequate margins, of local recurrence, and of the likelihood of missed areas of invasion. Inclusion of these elements in the pathology report is mandated by the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the College of American Pathologists.[29] Although reporting the architectural pattern is not currently required, we advocate doing so because certain histologic patterns can affect surgical decisions. For example, a pure micropapillary pattern (Figure 2) commonly predicts extensive disease, [30,31] which may require mastectomy because of the difficulty in achieving negative margins.

FIGURE 2

Pure Micropapillary Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS)

Margin status is the single most critical determinant of local control following breast conservation in patients with DCIS.[12,21,24,32,33] When surgeons provide accurate three-dimensional orientation of the specimen, the pathologist can accurately report the relationship of the DCIS to all six margins. In many cases, this will permit targeted re-excision rather than mastectomy for close/involved margins.[25,34] Numerous studies have shown that as the margin width increases, the risk of local failure decreases. What constitutes adequate margin width in DCIS is controversial; however, most authorities agree that margins of at least 3 mm are required for low- and intermediate-grade disease, while margins of 5 mm or greater are preferable for high-grade lesions, with special consideration for superficial and chest wall margins. Studies have shown that as many as 60% of patients with margins of less than 1.0 mm have residual DCIS coupled with a 35% chance of local recurrence. In addition, there are no significant differences in recurrence rates between margins that are positive and those that are less than 1 mm.[21] More importantly, Silverstein et al showed that only patients with margin widths of less than 1.0 mm benefited from the addition of radiation therapy; radiation did not reduce the recurrence rate for patients with clear margins of 1.0 mm or more.[12]

Should all women with conservatively treated DCIS receive radiation?

The pros and cons of irradiating conservatively treated patients with DCIS should be carefully weighed on a case-by-case basis. Large clinical trials (the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project [NSABP] protocol B-17, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] protocol 10853, and the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand DCIS Trial)[35-37] have unquestionably demonstrated that radiation is effective in reducing the risk of local recurrence by approximately 50%; the results of these trials led to the dogma that all women who undergo excision for DCIS should have radiation therapy. Unfortunately, none of the above trials prospectively collected the critical pathologic data needed to identify the characteristics of patients who benefited and to assess how much benefit was derived. Thus, subgroups that could be successfully treated by excision alone could not be defined. However, from a retrospective review of the existing pathologic data it is clear that most local recurrences, distant metastases, and deaths were in women with high-grade DCIS with margins that were close, involved, or of unknown status.[38,39] Furthermore, none of these trials showed that radiation had a beneficial effect on the most important outcome variables: distant recurrence, breast cancer–specific mortality, and overall survival.[35-37] These findings differ radically from those for invasive cancer, where the use of radiotherapy significantly improves the aforementioned outcomes.[40]

In contrast to the preceding trials, pathologic considerations were paramount for patients entered in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 5194 DCIS clinical trial, which evaluated excision only. Pathology central review required sequential embedding of the lesion, negative margins, and carefully defined DCIS size and grade before a patient was considered eligible. This trial prospectively identified a subset of women with small low- and intermediate-grade DCIS and negative margins of at least 3.0 mm, who could be successfully treated by excision alone.[41] Retrospective studies found a similar failure rate of 5% to 10% at 5 years in widely excised lesions with low- to intermediate-grade histology.[12,34] Based on these studies, an algorithm has been devised that is useful in predicting local recurrence for conservatively treated patients with DCIS. The University of Southern California/Van Nuys Prognostic Index (USC/VNPI) quantifies the five measurable prognostic factors known to be most important in predicting local recurrence: age, grade, size, presence or absence of comedo necrosis, and margin width.[22,42]

Should women with DCIS undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy?

Since DCIS is by definition a noninvasive process, affected women should not be at risk for metastasis. However, approximately 1% to 2% of women with DCIS do ultimately develop distant metastasis, presumably as a result of unrecognized invasive disease at the time of the initial excision or following an invasive recurrence.[43] Women with extensive high-grade DCIS, palpable or mammographic mass, pathological suspicion for invasion on core biopsy, or lymphovascular invasion without evidence of parenchymal invasion should undergo a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) at the time of lumpectomy. Moore et al found, among 470 patients with these high-risk features, that 3 patients (7%) had macrometastases and 4 patients (9%) had micrometastases; the presence of these metastases led to the patients being upstaged to stage I or II disease.[44] Thus, a critical role of SLNB in selected patients with pure DCIS on lumpectomy is to identify those with occult invasion. It is likely that those patients who develop systemic disease are a subset of patients who are LN-positive.[15] However, three retrospective series of women with DCIS and axillary sampling showed no reduction in survival when the lymph nodes were positive by immunohistochemical analysis only.[45]

What is the value of biomarkers in DCIS?

Identification of biological markers to supplement the histologically defined parameters that predict local recurrence in DCIS is an area of active investigation. Unfortunately, the expression level of many of these biomarkers (including steroid receptors, proliferation markers, cell-cycle regulation and apoptotic markers, angiogenesis-related proteins, epidermal growth factor receptor family receptors, and extracellular matrix–related proteins) correlates with the nuclear grade, and therefore may be a surrogate for grade but not an independent marker.[46] Moreover, discerning any independent prognostic implications for these proposed biomarkers, as highlighted by Lari et al,[46] is difficult because of the heterogeneous treatment, frequently small numbers of patients, and lack of inclusion of accepted parameters such as margin status. Although immunohistochemical evaluation of estrogen and progesterone receptors is frequently performed in the setting of DCIS, the Update Committee of the American Society of Clinical Oncology concluded that there are currently insufficient data to make a general recommendation for the use of ER status to guide decisions regarding tamoxifen treatment.[47]

Conclusions

The answer to the question posed by the title of this review is a resounding ‘yes!' for the vast majority of women. When specimens containing DCIS are carefully examined in a consistent manner, crucial information about size and margin status can be ascertained, allowing women with limited-extent low- or intermediate-grade DCIS to be treated by excision alone. In contrast, mastectomy may be required for some cases of large DCIS or pure micropapillary DCIS. Although some experts advocate adjuvant radiation for women who desire breast conservation and whose DCIS features are associated with recurrence rates of more than 10% to 15%, the critical studies of Silverstein et al raise questions about this practice-especially in light of the fact that the addition of radiation has no impact on overall survival[35-37] and may delay recurrence detection, resulting in a greater proportion of invasive recurrences than is seen with excision only.[13,14] Armed with the results of these follow-up studies and the appropriate clinicopathologic data, we can now tailor treatment of DCIS to the needs of the individual patient. In the premammographic era, DCIS was treated as one disease, resulting in mastectomy. We now know that breast conservation alone is curative for well-defined subsets of women. Our challenge in the future will be to address critically the long-accepted rationale for adjuvant radiation after excision for all women.

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

REFERENCES

1. Dupont W, Page D. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:146-51.

2. London S, Connolly J, Schnitt S, Colditz G. A prospective study of benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 1992;267:941-4.

3. Dupont W, Parl F, Hartmann W, et al. Breast cancer risk associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 1993;71:1258-65.

4. Hartmann L, Sellers T, Frost M, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229-37.

5. Sanders M, Schuyler P, Dupont W, Page D. The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2005;103:2481-4.

6. Collins L, Tamimi R, Baer H, et al. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1778-84.

7. Betsill W, Jr, Rosen P, Lieberman P, Robbins G. Intraductal carcinoma. Long-term follow-up after treatment by biopsy alone. JAMA. 1978;239:1863-7.

8. Saul S. Prone to error: earliest steps to find cancer. The New York Times. July 20, 2010.

9. Simpson J, Sanders M, Page D, editors. Diagnostic accuracy of ductal carcinoma in situ: results of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Trial 5194. USCAP; March 2011; San Antonio, TX.

10. Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, et al. Continued local recurrence of carcinoma 15-25 years after a diagnosis of low grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated only by biopsy. Cancer. 1995;76:1197-1200.

11. Collins LC, Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, et al. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1778-84.

12. Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Groshen S, et al. The influence of margin width on local control of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1455-61.

13. Guerra LE, Smith RM, Kaminski A, et al. Invasive local recurrence increased after radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg. 2008;196:552-5.

14. Wong JS, Kaelin CM, Troyan SL, et al. Prospective study of wide excision alone for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1031-6.

15. Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD. Should all patients undergoing breast conserving therapy for DCIS receive radiation therapy? No. One size does not fit all: an argument against the routine use of radiation therapy for all patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast who elect breast conservation. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:605-9.

16. Ozanne EM, Shieh Y, Barnes J, et al. Characterizing the impact of 25 years of DCIS treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:165-73.

17. Grin A, Horne G, Ennis M, O'Malley FP. Measuring extent of ductal carcinoma in situ in breast excision specimens: a comaprison of four methods. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:31-7.

18. Dadmanesh F, Fan X, Dastane A, et al. Comparative analysis of size estimation by mapping and counting number of blocks with ductal carcinoma in situ in breast excision specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:26-30.

19. O'Sullivan M, Li T, Freedman G, Morrow M. The effect of multiple reexcisions on the risk of local recurrence after breast conserving surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3133-40.

20. Silverstein M Lagios M, Recht A, et al. Image-detected breast cancer: state of the art diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:586-97.

21. Cheng L, Al-Kaisi NK, Gordon NH, et al. Relationship between the size and margin status of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast and residual disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1356-60.

22. Di Saverio S, Catena F, Santini D, et al. 259 patients with DCIS of the breast applying USC/Van Nuys prognostic index: a retrospective review with long term follow up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:405-16.

23. MacDonald HR, Silverstein MJ, Mabry H, et al. Local control in ductal carcinoma in situ treated by excision alone: incremental benefit of larger margins. Am J Surg. 2005;190:521-5.

24. Sigal-Zafrani B, Lewis JS, Clough KB, et al. Histological margin assessment for breast ductal carcinoma in situ: precision and implications. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:81-8.

25. Dillon MF, Mc Dermott EW, O'Doherty A, et al. Factors affecting successful breast conservation for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1618-28.

26. Neuschatz A, DiPetrillo T, Steinhoff M, et al. The value of breast lumpectomy margin assessment as a predictor of residual tumor burden in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 2002;94:1917-24.

27. Asjoe FT, Altintas S, Huizing MT, et al. The value of the Van Nuys Prognostic Index in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a retrospective analysis. Breast J. 2007;13:359-67.

28. Muffuz A, Barroso-Bravo S, Najera I, et al. Tumor size as predictor of microinvasion, invasion, and axillary metastasis in ductal carcinoma in situ. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:223-7.

29. Lester SC, Bose S, Chen YY, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with invasive carcinoma of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1515-38.

30. Patchefsky AS, Schwartz GF, Finkelstein SD, et al. Heterogeneity of intraductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer. 1989;63:731-41.

31. Bellamy CO, McDonald C, Salter DM, et al. Noninvasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: the relevance of histologic categorization. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:16-23.

32. Boland GP, Chan KC, Knox WF, et al. Value of the Van Nuys Prognostic Index in prediction of recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ after breast-conserving surgery. Br J Surg. 2003;90:426-32.

33. Neuschatz AC, DiPetrillo T, Steinhoff M, et al. The value of breast lumpectomy margin assessment as a predictor of residual tumor burden in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 2002;94:1917-24.

34. Macdonald HR, Silverstein MJ, Lee LA, et al. Margin width as the sole determinant of local recurrence after breast conservation in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg. 2006;192:420-2.

35. Fisher B, Land S, Mamounas E, et al. Prevention of invasive breast cancer in women with ductal carcinoma in situ: an update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:400-18.

36. Bijker N, Meijnen P, Peterse JL, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma-in-situ: ten-year results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized phase III trial 10853-a study by the EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3381-7.

37. Houghton J, George WD, Cuzick J, et al. Radiotherapy and tamoxifen in women with completely excised ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:95-102.

38. Fisher ER, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:429-38.

39. Bijker N, Peerse JL, Duchateau L, et al. Risk factors for recurrence and metastasis after breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10853. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2263-71.

40. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087-2106.

41. Hughes LL, Wang M, Page DL, et al. Local excision alone without irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5319-24.

42. Silverstein MJ. The University of Southern California/Van Nuys prognostic index for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg. 2003;186:337-43.

43. Julien JP, Bijker N, Fentiman IS, et al. Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet. 2000;355:528-33.

44. Moore KH, Sweeney KJ, Wilson ME, et al. Outcomes for women with ductal carcinoma-in-situ and a positive sentinel node: a multi-institutional audit. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2911-7.

45. Mabry H, Giuliano AE, Silverstein MJ. What is the value of axillary dissection or sentinel node biopsy in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ? Am J Surg. 2006;192:455-7.

46. Lari SA, Kuerer HM. Biological markers in DCIS and risk of breast recurrence: a systematic review. J Cancer. 2011;2:232-61.

47. Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5287-5312.

Gedatolisib Combo With/Without Palbociclib May Be New SOC in PIK3CA Wild-Type Breast Cancer

December 21st 2025“VIKTORIA-1 is the first study to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS with PAM inhibition in patients with PIK3CA wild-type disease, all of whom received prior CDK4/6 inhibition,” said Barbara Pistilli, MD.