Categorization of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients Will Help in Targeted Therapy Selection

Researchers at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine have parsed the large and heterogeneous triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) category of patients into 6 molecularly distinct subgroups. This may be an important step towards delineating these patients as specific genetic subtypes to channel them to appropriate targeted therapy trials.

Researchers at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine have parsed the large and heterogeneous triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) category of patients into six molecularly distinct subgroups. This may be an important step towards delineating these patients as specific genetic subtypes to channel them to appropriate targeted therapy trials. Defining these subgroups will facilitate drug discovery, clinical trial design, and novel biomarker identification. The research was published on July 1st in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

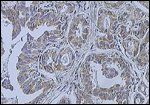

Breast cancer (infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast); source: Wikimedia Commons user Itayba

The tumors of TNBC patients lack estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression and also lack amplification of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Finding appropriate targeted treatments for TNBC patients is impossible without further molecular characterization because the TNBC category describes only what genetic alterations these tumors are lacking. As the first author and Cancer Center Director Jennifer Pietenpol, PhD stated, the term "triple-negative breast cancer is just a definition of what [the cancer] isn't."

Yet this category makes up 10% to 20% of all breast cancer and generally affects younger patients. TNBC tumors tend to be larger and of higher grade and are more aggressive. TNBC patients have a poorer prognosis and a higher rate of recurrence.

"It's a pretty significant health problem from the standpoint that 11% of Caucasians, 17% of Hispanics, and 25% of African Americans have this type of breast cancer," said Pietenpol.

The study

Study authors compiled the gene expression profiles from 21 breast cancer data sets. 587 TNBC cases out of 3247 breast cancers were identified and analyzed to identify genes that were either turned up (over-expressed) or turned down (silenced).

Six different TNBC subtypes were identified: two basal-like (BL1 and BL2), an immunomodulatory (IM), a mesenchymal (M), a mesenchymal stem–like (MSL), and a luminal androgen receptor (LAR) subtype. Importantly, these analyses allowed the researchers to identify cell line models that represent these subtypes. For example the M and MSL cell lines responded to a dual phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, NVP-BEZ235, and dasatinib. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway is important for cellular metabolism and proliferation and is often mutated in a range of different cancers. BEZ235 is being developed by Novartis and is currently in phase I and II trials for solid tumors and also for advanced breast cancer. Dasatinib (Sprycel) is being evaluated in solid tumors, including metastatic breast cancer and non–small-cell lung cancer.

Patient survival was analyzed by each TNBC subtype: relapse-free survival was significantly decreased in the LAR subtype compared with the BL1 subtype and MSL subtype (P < .05). Interestingly, distant metastasis-free survival did not vary between different patient subtypes. Neither tumor size nor grade was significantly different among the six subtypes (P < .0001). However, the entire patient subset had variable durations of treatment as well as treatment type.

Follow-up research will need to validate these subtypes through further tumor characterization as well as utilization of cell line models. Further genomic analysis including DNA copy number, microRNA, and whole genomic sequencing will also aid identification of driver signaling pathways that are important in these tumors.

"In our opinion, the big breakthrough is just being able to say 'this isn't one disease,'" said Pietenpol. "This really is the first step in translating genomic information into personalizing therapy for women with a very difficult-to-treat breast cancer."