Coming to Grips With Hand-Foot Syndrome

Hand-foot syndrome is a localized cutaneous side effect associatedwith the administration of several chemotherapeutic agents, includingthe oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine (Xeloda). It is never life-threateningbut can develop into a painful and debilitating condition thatinterferes with patients' normal daily activities and quality of life. Severalsymptomatic/prophylactic treatments have been used to alleviatehand-foot syndrome, but as yet there is insufficient prospective clinicalevidence to support their use. The only proven method of managinghand-foot syndrome is treatment modification (interruption and/or dosereduction), and this strategy is recommended for patients receivingcapecitabine. Retrospective analysis of safety data from two largephase III trials investigating capecitabine as first-line therapy in patientswith colorectal cancer confirms that this strategy is effective inthe management of hand-foot syndrome and does not impair the efficacyof capecitabine. This finding is supported by studies evaluatingcapecitabine in metastatic breast cancer. Notably, the incidence andmanagement of hand-foot syndrome are similar when capecitabine isadministered in the metastatic and adjuvant settings, as monotherapy,or in combination with docetaxel (Taxotere). It is important that patientslearn to recognize the symptoms of hand-foot syndrome, so thatprompt symptomatic treatment and treatment modification strategiescan be implemented.

ABSTRACT: Hand-foot syndrome is a localized cutaneous side effect associated with the administration of several chemotherapeutic agents, including the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine (Xeloda). It is never life-threatening but can develop into a painful and debilitating condition that interferes with patients' normal daily activities and quality of life. Several symptomatic/prophylactic treatments have been used to alleviate hand-foot syndrome, but as yet there is insufficient prospective clinical evidence to support their use. The only proven method of managing hand-foot syndrome is treatment modification (interruption and/or dose reduction), and this strategy is recommended for patients receiving capecitabine. Retrospective analysis of safety data from two large phase III trials investigating capecitabine as first-line therapy in patients with colorectal cancer confirms that this strategy is effective in the management of hand-foot syndrome and does not impair the efficacy of capecitabine. This finding is supported by studies evaluating capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer. Notably, the incidence and management of hand-foot syndrome are similar when capecitabine is administered in the metastatic and adjuvant settings, as monotherapy, or in combination with docetaxel (Taxotere). It is important that patients learn to recognize the symptoms of hand-foot syndrome, so that prompt symptomatic treatment and treatment modification strategies can be implemented.

Hand-foot syndrome, also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, palmar-plantar erythema, acral erythema, and the Burgdorf reaction, is a localized, cutaneous side effect associated with a wide range of systemic chemotherapy agents. The condition, probably first described in 1974 in a patient receiving mitotane (Lysodren),[1] was defined in a 1982 case study of a patient receiving a cytarabine-containing chemotherapy regimen.[2]

The development of hand-foot syndrome appears to be predominantly drug and dose dependent, with peak plasma drug concentrations, total cumulative dose, and administration schedule affecting onset and severity.[ 3] Consequently, the time of onset is variable, ranging from 24 hours to 10 months after the start of chemotherapy. Hand-foot syndrome is usually self-limiting and rarely leads to hospitalization or life-threatening manifestations. However, if it is not recognized early and managed effectively, an initially mild, cutaneous reaction can progress to an extremely painful and debilitating condition that can have a considerable impact on a patient's quality of life.

New insights into the management of hand-foot syndrome have been provided by clinical trials evaluating the novel oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine (Xeloda). Capecitabine was rationally designed to generate fluorouracil (5-FU) preferentially in tumor tissue[4] and offers sustained 5-FU delivery to tumors, thus mimicking continuous-infusion 5-FU. Like continuous-infusion 5-FU, one of the side effects of treatment with capecitabine is hand-foot syndrome.

Capecitabine monotherapy is a highly active oral treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal or breast cancer.[5-13] With favorable safety, capecitabine is also well suited for ad ministration in the adjuvant setting and in combination with other cytotoxic agents. Notably, in anthracycline-pretreated metastatic breast cancer, the combination of capecitabine with docetaxel (Taxotere) conferred a significant survival benefit compared with singleagent docetaxel.[14]

As monotherapy and in combination regimens, capecitabine is well established in the treatment of metastatic breast and colorectal cancer. In this review, data from clinical trials evaluating capecitabine are analyzed with a view to demonstrating the optimal management of hand-foot syndrome in patients receiving the drug. The experience with capecitabine provides a large body of evidence supporting early recognition, prompt treatment interruption, and dose reduction as the optimal strategy for management.

Clinical Manifestation and Diagnosis

The clinical manifestation of handfoot syndrome has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.[15] Its clinical signs and symptoms are distinctive, and diagnosis is usually based on the clinical setting and treatment history.[ 3,16,17] Prior to onset, individuals often experience dysesthesia or paresthesia in the palms and soles, including numbness or tingling. Over the next 3 to 4 days, painful swelling and erythema develop progressively in these areas, particularly on the pads of the distal phalanges, which can disrupt the patient's ability to pursue normal daily activities. If the condition progresses further, the indurated erythematous plaques darken, and over the next few days, develop central areas of pallor. The plaques may subsequently blister and desquamate, and then reepithelialize as part of the healing process.

FIGURE 1

Clinical Manifestations of Hand-Foot Syndrome

Blisters tend to develop over pressure areas and remain limited to the palms and, less frequently, the soles. Occasionally, a mild, generalized erythema or morbilliform rash may coincide with the acral reaction. Rarely, deep ischemic necrosis develops at the sites of blister formation. Figure 1 shows the clinical manifestation of hand-foot syndrome, including the characteristic mild erythema developing on the soles of the feet and palms of the hands, as well as a case that has been allowed to progress to severe ulcerating disease.

Histologic studies suggest that the acute erythema of hand-foot syndrome is nonspecific and consistent with a generalized toxicity.[3,18] Because the reaction is usually limited to the palms and soles, features of acral regions such as temperature gradients, vascular anatomy, a relatively rapidly renewing epidermis, and a high concentration of eccrine glands are implicated in its pathogenesis.[3,17] Electron microscopy has shown that the basement membrane remains intact and eccrine sweat gland or duct damage appears to be absent.[19]

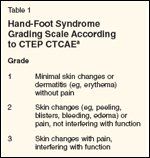

TABLE 1

Hand-Foot Syndrome Grading Scale According to CTEP CTCAE

Until recently, there was no standard grading system for hand-foot syndrome. However, the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTEP CTCAE) now includes a standard grading scheme for hand-foot syndrome (Table 1). Many of the published clinical trials of agents associated with hand-foot syndrome were initiated prior to the introduction of a standard grading scheme. In capecitabine trials, hand-foot syndrome has been graded 1 to 3, based on functional criteria: Grade 1 was defined as numbness, dysesthesia/paresthesia, tingling, painless swelling, or erythema not disrupting normal activities; grade 2 was defined as painful erythema with swelling that disrupts daily activities; and grade 3 was defined as moist desquamation, ulceration, blistering, severe pain, or any symptoms leading to an inability to perform daily activities.[8]

Drugs Associated With Hand-Foot Syndrome

Although this review focuses on the management of hand-foot syndrome in patients receiving capecitabine, it should be remembered that this syndrome is associated with prolonged administration of a wide range of cytotoxic agents. No feature common to the cytotoxic agents causing the condition has been identified, and the cause of hand-foot syndrome remains unknown. Ethnicity may be implicated but has not been proven, and a recently published Korean study ruled out IVS14+1G→A point mutation as a possible correlate with the severity of hand-foot syndrome.[20]

Anthracyclines are associated with hand-foot syndrome. Although rare with intravenous (IV) bolus anthracycline therapy, it develops more frequently in patients receiving these drugs administered as a continuous infusion. The syndrome was dose-limiting in a phase I study of infused epirubicin (Ellence)[21] and was a major toxicity in a phase II study evaluating infused doxorubicin in patients with metastatic sarcoma.[22] Liposomal daunorubicin (DaunoXome) at high doses has been associated with the condition,[23] and a particularly high incidence of severe hand-foot syndrome (27%) was reported with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil).[24] Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with paclitaxel was associated with an even higher incidence of grade 3 hand-foot syndrome (51%).[25] The condition has also been reported less commonly with the cytotoxic agents hydroxyurea, methotrexate, mercaptopurine (Purinethol), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar), vinorelbine (Navelbine), mitotane, and the taxanes.[3,26-30]

Hand-foot syndrome is a common side effect in patients receiving highdose chemotherapy regimens prior to bone marrow transplants for leukemia. It is important to differentiate between hand-foot syndrome and acute graftvs- host disease (GVHD) in this setting, and both disorders may occur concomitantly.[ 3,31] In particular, hand-foot syndrome is frequently associated with prolonged administration of the nucleoside analog cytarabine,[32,33] and incidences of 39% have been reported in patients receiving cytarabine-based combination therapy regimens.[34] Not surprisingly, hand-foot syndrome is also observed with troxacitabine (Troxatyl), an analog of cytarabine that is investigational in the United States.[35-38]

Hand-Foot Syndrome and the Fluoropyrimidines

Cutaneous reactions in patients receiving 5-FU are dose and schedule dependent. Hand-foot syndrome is rare with IV bolus 5-FU but is doselimiting when 5-FU is administered as a continuous infusion-a pattern first noted by Lokich and Moore in 1984.[16] A meta-analysis of data from randomized trials comparing bolus and continuous-infusion 5-FU in 1,219 patients with advanced colorectal cancer confirmed that handfoot syndrome is significantly more common with continuous-infusion 5-FU (34% vs 13% with bolus 5-FU; P < .0001).[39]

With continuous-infusion 5-FU, the risk of developing hand-foot syndrome is significantly higher in older patients (P = .009), as well as in female patients (P = .04). Although individual data on time to toxicity were not available, survival duration had a significant impact on the risk of developing hand-foot syndrome (P < .0001), suggesting strongly that its incidence is linked to the duration of treatment.[39] The incidence of hand-foot syndrome with continuous infusion 5-FU has not limited the clinical use of infused regimens, which have demonstrated superiority over bolus 5-FU in terms of response rate and overall survival (P < .05).[40]

Hand-foot syndrome has also been reported with the oral fluoropyrimidines, including tegafur (Ftorafur),[41,42] UFT (uracil plus tegafur),[43] S-1 (tegafur plus 5- chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine and potassium oxonate),[44,45] oral 5-FU plus eniluracil (Cytefuran),[46] emitefur (BOF-A2),[47] as well as capecitabine.[ 5,6,8-11,13,48]

Management of Hand-Foot Syndrome

It has been suggested that the development of hand-foot syndrome in patients receiving chemotherapy can be prevented to some extent by lifestyle changes that avoid aggravation to the hands and feet. Potential irritants include exposure to extremes of temperature, ill-fitting shoes or tightfitting clothing, excessive exercise, and the use of topical anesthetics or diphenhydramine-containing creams.[49,50] Treatment is usually supportive, including measures to reduce pain and discomfort and prevent secondary infection.

To date, the only method shown to effectively manage hand-foot syndrome is interruption of treatment and, if necessary, dose reduction. Treatment interruption and dose reduction constitute a recommended strategy for the management of hand-foot syndrome with several agents, including pegylated liposomal doxorubicin,[51-53] continuous-infusion 5-FU,[54-56] and capecitabine.[8,57]

Treatments that relieve the cutaneous symptoms are also being investigated as preventive/prophylactic measures. A controlled study showed that the concomitant administration of pyridoxine delayed onset and reduced the severity of cutaneous toxicity occurring with the infusion of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in a canine model,[58] but its efficacy has not been clearly established in the clinical setting.[59] Topical dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is effective for the treatment of tissue extravasation reactions occurring with IV doxorubicin,[ 60,61] but its role in the management of hand-foot syndrome remains to be clearly determined.[62]

Other studies suggest that a petroleum/ lanolin-based ointment containing the antiseptic hydroxyquinoline sulphate ('Bag Balm'),[63] oral dexamethasone,[ 64] and the cytoprotectant amifostine (Ethyol)[65] may also be effective in alleviating handfoot syndrome. There is a possible clinical benefit for hand-foot syndrome with Biafine, an emollient currently being investigated prophylactically for radiation dermatitis,[66] but no formal studies of this agent for hand-foot syndrome have been conducted. Similarly, another gel-based agent, Carmol 40, may have benefit in hand-foot syndrome but has not been formally investigated. However, as emollients only relieve the symptoms of this condition, it is not recommended that they be used as a substitute for treatment interruption or dose reduction.

One case report has highlighted the prophylactic use of a nicotine patch for hand-foot syndrome.[67] A nicotine patch was applied to the patient's skin 1 hour before 5-FU infusion and was removed 1 hour after completion of each 24-hour infusion. The patient's desquamation, erythema, and hyperpigmentation all completely resolved despite continued chemotherapy. It is thought that the vasoconstricting properties of the patch may decrease delivery of 5-FU to the skin.

Thalidomide (Thalomid) is an effective treatment for some cutaneous conditions such as erythema nodosum leprosum, Sjgren's syndrome, and acute GVHD.[68] The pathogenesis of these conditions is associated with disturbances in cellular immunity, and the efficacy of thalidomide is considered to be due primarily to its immunosuppressive properties. The rationale behind the use of this agent for handfoot syndrome is unclear. The benefits of thalidomide in patients with hand-foot syndrome may be limited to its analgesic/sedative properties.

Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibition has also been investigated as a systemic strategy for reducing chemotherapy- associated hand-foot syn- drome. The effect of celecoxib (Celebrex), a specific COX-2 inhibitor, on the incidence of capecitabine-associated hand-foot syndrome was evaluated in a retrospective study in 67 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.[ 69,70] The addition of celecoxib to capecitabine therapy was associated with a reduced incidence of handfoot syndrome (12.5% vs 34.3%; P = .037) and grade 3/4 diarrhea (3.1% vs 28.6%; P = .005). Furthermore, clinical outcomes such as tumor response rate, tumor stabilization rate, and time to progression were also improved in patients receiving celecoxib and capecitabine therapy. Together with the large body of clinical evidence supporting the combination of capecitabine and celecoxib, these preliminary data have provided the rationale for a prospective evaluation of the capecitabine/celecoxib regimen.

Optimizing Management

TABLE 2

Incidence of Hand-Foot Syndrome With Capecitabine, Reported from Phase II/III Trials

The standard capecitabine monotherapy regimen is 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days followed by a 7-day rest period. Clinical trials have shown that the incidence of hand-foot syndrome with the standard capecitabine dose and schedule is similar in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer[5,6] or metastatic breast cancer,[ 8,11-13,48,71] including older patients (n = 61; median age = 69 years) with anthracycline-pretreated breast cancer[10] (Table 2). These trials have also shown that hand-foot syndrome occurs predominantly at only grade 1/2 severity (mild-to-moderate intensity). As with continuous 5-FU infusion, hand-foot syndrome is more common with capecitabine than with bolus IV 5-FU/leucovorin treatment when administered as firstline therapy for colorectal cancer.

Data from large, multicenter trials in patients with metastatic breast or colorectal cancer have demonstrated that treatment interruption and/or dose reduction is effective in the management of hand-foot syndrome, without compromising efficacy.[57,71] These trials included predefined schemes for treatment interruption and dose reduction for the management of grade 2-4 side effects, including hand-foot syndrome.

A prospectively designed, integrated analysis of the data from two large phase III trials in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (n = 1,207) demonstrates that 53% of patients receiving capecitabine experienced hand-foot syndrome, compared with 17% of those receiving bolus IV 5-FU/leucovorin (P < .001).[72] However, the overall safety profile of capecitabine was improved compared with the Mayo Clinic regimen, with a significantly (P < .001) lower incidence of diarrhea, stomatitis, nausea, and alopecia.

In the phase III trials in metastatic colorectal cancer, hand-foot syndrome was the side effect that most commonly led to treatment interruption or dose reduction in the capecitabine group (182 of 596 patients).[57] The median time to first onset of grade 3 hand-foot syndrome was later (88 days) than for other grade 3/4 side effects: 36 days for diarrhea (n = 78), 47 days for stomatitis (n = 13), 15 days for vomiting (n = 17), and 12 days for nausea (n = 15). Hand-foot syndrome was reversible with treatment interruption, and the median duration of grade 3 hand-foot syndrome was 13 days.

This study also confirmed that a reduction in the dose of capecitabine in patients with grade 2/3 hand-foot syndrome was effective in preventing its recurrence.[57] Following dose reduction (138 patients; 30%), only 25 patients experienced a grade 2 recurrence and 20 patients experienced a grade 3 recurrence. Only two patients required pain relief. Furthermore, hand-foot syndrome caused hospitalization of just two patients-less than 24 hours in one patient and less than 8 hours in the other. Importantly, efficacy was maintained in patients following capecitabine dose reduction. A time-dependent, Cox regression analysis showed that no increase in the risk of disease progression occurred in patients who required a dose reduction for adverse events to either 75% or 50% of the baseline capecitabine dose (hazard ratio = 0.97; P = .78).

Similarly, in a large, multicenter phase II study evaluating capecitabine in patients with paclitaxelpretreated metastatic breast cancer (n = 162), hand-foot syndrome was the most common treatment-related adverse event (56% of patients, with grade 3 in only 10%).[71] In this study, hand-foot syndrome led to dose modification in 27% of patients and dose reduction was effective in preventing both recurrence and worsening of the syndrome. All patients who required a dose reduction for grade 3 handfoot syndrome improved, as did the majority (88%) of those requiring dose reduction for grade 2. This study also confirmed that patients requiring dose modification for management of adverse events experienced no relevant increase in the risk of disease progression compared with those not requiring dose modification (hazard ratio = 1.02; P = .935).

In patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, subpopulation analyses according to age indicate that the incidence of grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events, including grade 3 hand-foot syndrome, is increased in patients aged 80 years or older receiving capecitabine.[57] Further analyses showed that the decreased tolerability of capecitabine in older patients is caused primarily by an agerelated decline in renal function. Dosing guidelines, therefore, recommend a lower starting dose of capecitabine (950 mg/m2 twice daily on days 1-14, followed by a 7-day rest period) in patients with moderate renal impairment (baseline creatinine clearance: 30-50 mL/min, calculated according to the Cockroft-Gault formula). In addition, capecitabine is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment at baseline (baseline creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).

Novel Capecitabine-Based Strategies Not Limited by Hand-Foot Syndrome

Based on significantly superior antitumor activity and improved safety achieved with first-line capecitabine vs 5-FU/leucovorin (Mayo Clinic regimen) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, capecitabine has been evaluated as adjuvant treatment for Dukes' C colon cancer. In a multinational, phase III study, patients with surgically resected Dukes' C colon cancer were randomized to receive 24 weeks of treatment with standard capecitabine monotherapy (n = 996) or 5-FU/leucovorin (Mayo Clinic regimen, n = 974). The recently reported results of the planned safety analysis showed that the improved safety profile of capecitabine in the metastatic setting was mirrored in the adjuvant setting.[73] As in the metastatic setting, hand-foot syndrome was the most common treatment-related adverse event with adjuvant capecitabine, occurring in 61% of patients overall and at grade 3 intensity in only 18% of patients. Although hand-foot syndrome was the adverse event most frequently leading to dose modification (31% of patients), it was effectively managed with this strategy.

REFERENCE GUIDE

Therapeutic Agents

Mentioned in This Article

Amifostine (Ethyol)

Capecitabine (Xeloda)

Celecoxib (Celebrex)

Cyclophosphamide

(Cytoxan, Neosar)

Cytarabine

Daunorubicin, liposomal

(DaunoXome)

Dexamethasone

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

Docetaxel (Taxotere)

Doxorubicin

Doxorubicin, liposomal (Doxil)

Emitefur (BOF-A2)

Eniluracil (Cytefuran)

Epirubicin (Ellence)

Fluorouracil (5-FU)

Hydroxyurea

Irinotecan (Camptosar)

Leucovorin

Mercaptopurine (Purinethol)

Methotrexate

Mitotane (Lysodren)

Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

Paclitaxel

Pyridoxine

S-1 (tegafur plus 5-chloro-2,4-

dihydroxypyridine and

potassium oxonate)

Tegafur (Ftorafur)

Thalidomide (Thalomid)

Troxacitabine (Troxatyl)

UFT (uracil plus tegafur)

Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

Brand names are listed in parentheses only if a drug is not available generically and is marketed as no more than two trademarked or registered products. More familiar alternative generic designations may also be included parenthetically.

The hand-foot syndrome that occurs in association with capecitabine/ docetaxel combination therapy is also effectively managed by dose interruption and/or reduction. In a phase III trial comparing capecitabine/docetaxel and single-agent docetaxel therapy, anthracycline-pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients received 3-weekly docetaxel alone at 75 mg/m2 (n = 255) or in combination with capecitabine at 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days followed by a 7-day rest period (n = 251).[14] The combination regimen was associated with a manageable toxicity profile. Together with gastrointestinal side effects, hand-foot syndrome was more common with combination therapy, whereas myalgia, arthralgia, and neutropenic fever/sepsis were more common with single-agent docetaxel. Notably, the incidence of hand-foot syndrome reported with the combination regimen (63%, including 24% grade 3) was similar to that reported in trials of capecitabine monotherapy in metastatic breast cancer.[9-13]

Although hand-foot syndrome was the adverse event most frequently precipitating treatment interruption (11% of patients), dose reduction was effective in preventing the recurrence of hand-foot syndrome. A retrospective analysis demonstrated that dose modification had no effect on efficacy; the hazard ratio for patients with vs without dose reductions in the combination arm was 0.84 (P = .42), indicating a 16% reduction in disease progression for patients with dose reduction. It was also notable that the higher incidence of hand-foot syndrome observed in patients receiving the combination regimen did not adversely affect quality of life (global health score). In summary, the incidence and management of hand-foot syndrome is similar when capecitabine is administered as monotherapy or in combination with docetaxel.

Hand-foot syndrome occurring when capecitabine is used in combination with other agents (eg, irinotecan [Camptosar], oxaliplatin [Eloxatin]) is not aggravated in frequency or severity. The incidence of grade 3 handfoot syndrome in the Intermittent Oral Capecitabine in Combination with Intravenous Oxaliplatin (XELOX) trial[ 74] was 3%, and in the capecitabine plus irinotecan (XELIRI) trial[75] was 6%.

Conclusions

Hand-foot syndrome is a cutaneous side effect typically associated with prolonged exposure to a wide range of chemotherapy agents, including capecitabine. Diagnosis is relatively straightforward due to the distinctive rash that develops on the palms and soles of patients. It is unclear what factors influence the development of this syndrome, but the unusual localization of the rash implicates local factors such as temperature, blood flow, or a high concentration of eccrine sweat glands. Although handfoot syndrome is not life-threatening, as a cutaneous condition affecting the hands and feet it can cause significant discomfort and impairment of function leading to worsened quality of life in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Treatment interruption and dose modification remain the only methods shown to effectively manage hand-foot syndrome, but supportive measures to reduce pain and discomfort and prevent secondary infection are important. Safety data from large, multicenter trials of capecitabine show that it can be effectively managed by treatment interruption and, if necessary, dose reduction, without compromising efficacy. In contrast to IV agents with long half-lives, the oral administration of capecitabine enables immediate and effective treatment modification at the first appearance of moderate or more severe hand-foot syndrome (grade 2/3). The twice-daily dosing schedule provides numerous opportunities in each cycle to reduce the dose to an individual's tolerable dose level.

Our recommendation is that the capecitabine dose be reduced by 25% at the first appearance of grade 2 handfoot syndrome. These new dosing recommendations are currently being applied in many prospective clinical trials and should further optimize the management of this condition in patients receiving capecitabine.

Early recognition is key to the management of hand-foot syndrome, and patient education and follow-up are essential. All patients receiving capecitabine, or any of the other agents causing this condition, should be taught to recognize the symptoms and their severity. Patients receiving capecitabine should be taught to interrupt treatment at the first appearance of moderate or more severe hand-foot syndrome and to seek further advice from their doctor, nurse, or pharmacist. Appropriate management will enable patients to derive the maximum benefit from the high activity, favorable safety, and convenience of oral capecitabine.

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

Acknowledgements:The authors wish to thank Dr. J Lokich, Cancer Center of Boston, for his assistance.

References:

1.

Zuehlke RL: Erythematous eruption of thepalms and soles associated with mitotanetherapy. Dermatologica 148:90-92, 1974.

2.

Burgdorf WH, Gilmore WA, Ganick RG:Peculiar acral erythema secondary to high-dosechemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia.Ann Intern Med 97:61-62, 1982.

3.

Baack BR, Burgdorf WH: Chemotherapyinducedacral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol24:457-461, 1991.

4.

Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, et al: Designof a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate,capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracilselectively in tumours by enzymes concentratedin human liver and cancer tissue. EurJ Cancer 34:1274-1281, 1998.

5.

Hoff PM, Ansari R, Batist G, et al: Comparisonof oral capecitabine versus intravenousfluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatmentin 605 patients with metastatic colorectalcancer: Results of a randomized phase III study.J Clin Oncol 19:2282-2292, 2001.

6.

Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Cassidy J, etal: Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin (MayoClinic regimen) in patients with metastaticcolorectal cancer: Results of a large phase IIIstudy. J Clin Oncol 19:4097-4106, 2001.

7.

Twelves C: Capecitabine as first-line treatmentin colorectal cancer. Pooled data from twolarge, phase III trials. Eur J Cancer 38(suppl2):S15-S20, 2002.

8.

Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, et al:Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine inpaclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer.J Clin Oncol 17:485-493, 1999.

9.

Blum JL, Dieras V, Lo Russo PM, et al:Multicenter, phase II study of capecitabine intaxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients.Cancer 92:1759-1768, 2001.

10.

O'Shaughnessy J, Blum J, MoiseyenkoV, et al: Randomized, open-label, phase II trialof oral capecitabine (Xeloda) versus a referencearm of intravenous CMF (cyclophosphamide,methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil) as firstlinetherapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer.Ann Oncol 12:1247-1254, 2001.

11.

Fumoleau P, Largillier P, Clippe C, etal: Multicentre, phase II study evaluatingcapecitabine monotherapy in patients withanthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastaticbreast cancer. Eur J Cancer 40:536-542, 2004.

12.

Maung K: Capecitabine/bevacizumabcompared to capecitabine alone in pretreatedmetastatic breast cancer: Results of a phase IIIstudy. Clin Breast Cancer 3:375-377, 2003.

13.

Reichardt P, von Minckwitz G, Thuss-Patience PC, et al: Multicenter phase II studyof oral capecitabine (Xeloda) in patients withmetastatic breast cancer relapsing after treatmentwith a taxane-containing therapy. AnnOncol 14:1227-1233, 2003.

14.

O'Shaughnessy J, Miles D, Vukelja S,et al: Superior survival with capecitabineplus docetaxel combination therapy inanthracycline-pretreated patients with advancedbreast cancer: Phase III trial results. JClin Oncol 20:2812-2823, 2002.

15.

Nagore E, Insa A, SanmartÃn O: Antineoplastictherapy-induced palmar plantarerythrodysaesthesia (‘hand-foot') syndrome.Incidence, recognition and management. Am JClin Dermatol 1:225-234, 2000.

16.

Lokich JJ, Moore C: Chemotherapy-associatedpalmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome.Ann Intern Med 101:798-800, 1984.

17.

Cohen PR: Acral erythema: A clinicalreview. Cutis 51:175-179, 1993.

18.

Gordon KB, Tajuddin A, Guitart J, et al:Hand-foot syndrome associated with liposomeencapsulateddoxorubicin therapy. Cancer75:2169-2173, 1995.

19.

Levine LE, Medenica MM, Lorincz AL,et al: Distinctive acral erythema occurring duringtherapy for severe myelogenous leukemia.Arch Dermatol 121:102-104, 1985.

20.

Park YH, Ryoo BY, Lee HJ, et al: Highincidence of severe hand-foot syndrome duringcapecitabine-docetaxel combination chemotherapy.Ann Oncol 14:1691-1692, 2003.

21.

de Vries EG, Greidanus J, Mulder NH,et al: A phase I and pharmacokinetic study with21-day continuous infusion of epirubicin. JClin Oncol 5:1445-1451, 1987.

22.

Samuels BL, Vogelzang NJ, Ruane M,et al: Continuous venous infusion of doxorubicinin advanced sarcomas. Cancer Treat Rep71:971-972, 1987.

23.

Hui YF, Cortes JE: Palmar-plantarerythrodysesthesia syndrome associated withliposomal daunorubicin. Pharmacotherapy20:1221-1223, 2000.

24.

Smith DH, Johnston SR, Gordon AN, etal: Economic evaluation of Doxil/Caelyx vstopotecan for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma:The UK perspective (abstract 808).Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20:203a, 2001.

25.

Woll PJ, Carmichael J, Calvert AH, etal: Doxil/Caelyx (D) plus paclitaxel (T) in patientswith metastatic breast cancer (MBCa):Update of a phase II efficacy and safety study(abstract 2017). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol20:67b, 2001.

26.

Gallagher J: Management of cutaneoussymptoms. Semin Oncol Nurs 4:239-247, 1995.

27.

Zimmerman GC, Keeling JH, Burris HA,et al: Acute cutaneous reactions to docetaxel,a new chemotherapeutic agent. Arch Dermatol131:202-206, 1995.

28.

Hoff PM, Valero V, Ibrahim N, et al:Hand-foot syndrome following prolonged infusionof high doses of vinorelbine. Cancer82:965-969, 1998.

29.

Rosner F: Hand-foot syndrome followingprolonged infusion of high doses ofvinorelbine. Cancer 83:1054-1055, 1998.

30.

de Argila D, Dominguez JD, Iglesias L:Taxol-induced acral erythema. Dermatology192:377-378, 1996.

31.

Crider MK, Jansen J, Norins AL, et al:Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema in patientsreceiving bone marrow transplantation.Arch Dermatol 122:1023-1027, 1986.

32.

Herzig RH, Wolff SN, Lazarus HM, etal: High-dose cytosine arabinoside therapy forrefractory leukemia. Blood 62:361-369, 1983.

33.

Kroll SS, Koller CA, Kaled S, et al: Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema: Desquamatinglesions involving the hands and feet.Ann Plast Surg 23:263-265, 1989.

34.

Oksenhendler E, Landais P, CordonnierC, et al: Acral erythema and systemic toxicityrelated to CHA induction therapy in acutemyeloid leukemia. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol25:1181-1185, 1989.

35.

Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Garcia-ManeroG, et al: A phase II study of troxacitabine, anovel nucleoside analog, in patients with leukemia(abstract 1212). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol20:304a, 2001.

36.

Dent SF, Arnold A, Stewart D, et al:NCIC CTG IND 120: Phase II study oftroxacitabine (BCH-4556) in patients with advancednon-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)(abstract 2786). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol20:259b, 2001.

37.

Giles FJ, Garcia-Manero G, Cortes JE,et al: Phase II study of troxacitabine, a noveldioxolane nucleoside analog, in patients withrefractory leukemia. J Clin Oncol 20:656-664,2002.

38.

Moore MJ, Chi K, Ernst S, et al: A phaseII study of troxacitabine in patients with advancedand/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma.NCIC CTG IND.119 (abstract 768). Proc AmSoc Clin Oncol 20:193a, 2001.

39.

Meta-analysis Group in Cancer: Efficacyof intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracilcompared with bolus administration inadvanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol16:301-308, 1998a.

40.

Meta-analysis Group in Cancer: Toxicityof fluorouracil in patients with advancedcolorectal cancer: Effect of administrationschedule and prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol16:3537-3541, 1998b.

41.

Jucgla A, Sais G, Navarro M, et al:Palmoplantar keratoderma secondary tochronic acral erythema due to tegafur. ArchDermatol 131:364-365, 1995.

42.

Bastida J, Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S:Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema due toTegafur. Arch Derm Venereol 77:72-73, 1997.

43.

Rivera E, Hyzinski M, Hutchins L, et al:A study of UFT + leucovorin (L) given as athree times daily (TID) regimen in the treatmentof patients (Pts) with metastatic breastcancer (MBC) (abstract 1989). Proc Am SocClin Oncol 20:60b, 2001.

44.

van Groeningen CJ, Peters GJ,Schornagel JH, et al: Phase I clinical and pharmacokineticstudy of oral S-1 in patients withadvanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 18:2772-2779, 2000.

45.

Elasmar SA, Saad ED, Hoff PM: Casereport: Hand-foot syndrome induced by the oralfluoropyrimidine S-1. Jpn J Clin Oncol 31:172-174, 2001.

46.

Baker SD, Diasio RB, O'Reilly S, et al:Phase I and pharmacologic study of oral fluorouracilon a chronic daily schedule in combinationwith the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenaseinactivator eniluracil. J Clin Oncol18:915-926, 2000.

47.

Nemunaitis J, Eager R, Twaddell T, etal: Phase I assessment of the pharmacokinetics,metabolism, and safety of emitefur in patientswith refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol18:3423-3434, 2000.

48.

Blum JL: The role of capecitabine, anoral, enzymatically activated fluoropyrimidine,in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.Oncologist 6:56-64, 2001.

49.

Pike K: Hand-foot syndrome. OncolNurs Forum 28:1519-1520, 2001.

50.

Caelyx. (product monograph).Kenilworth, NJ: Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals,2000.

51.

Uziely B, Jeffers S, Isacson R, et al: Liposomaldoxorubicin: Antitumor activity andunique toxicities during two complementaryphase I studies. J Clin Oncol 13:1777-1785,1995.

52.

Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, etal: Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: Arandomized phase III study of pegylated liposomaldoxorubicin versus topotecan. J ClinOncol 19:3312-3322, 2001.

53.

Doxil (prescribing information). ALZAPharmaceuticals, Mountain View, Calif, 2001.

54.

Lokich JJ, Ahlgren JD, Gullo JJ, et al: Aprospective randomized comparison of continuousinfusion fluorouracil with a conventionalbolus schedule in metastatic colorectalcarcinoma: A Mid-Atlantic Oncology Programstudy. J Clin Oncol 7:425-432, 1989.

55.

Comandone A, Bretti S, La Grotta G, etal: Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndromeassociated with 5-fluorouracil treatment. AnticancerRes 13:1781-1783, 1993.

56.

Fabian CJ, Molina R, Slavik M, et al:Pyridoxine therapy for palmar-plantarerythrodysesthesia associated with continuous5-fluorouracil infusion. Invest New Drugs 8:57-63, 1990.

57.

Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, etal: First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastaticcolorectal cancer: A favorable safety profilecompared with IV 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin.Capecitabine CRC Study Group. AnnOncol 13:566-575, 2002.

58.

Vail DM, Chun R, Thamm DH, et al:Efficacy of pyridoxine to ameliorate the cutaneoustoxicity associated with doxorubicincontaining pegylated (Stealth) liposomes: Arandomized, double-blind clinical trial using acanine model. Clin Cancer Res 4:1567-1571,1998.

59.

Lauman MK, Mortimer J: Effect of pyridoxineon the incidence of palmar plantarerythroderma (PPE) in patients receivingcapecitabine (abstract 1565). Proc Am Soc ClinOncol 20:392a, 2001.

60.

Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al:Topical dimethylsulfoxide for the preventionof soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicantcytotoxic drugs: A prospective clinicalstudy. J Clin Oncol 13:2851-2855, 1995.

61.

Olver IN, Aisner J, Hament A, et al: Aprospective study of topical dimethyl sulfoxidefor treating anthracycline extravasation. JClin Oncol 6:1732-1735, 1988.

62.

Lopez AM, Wallace L, Dorr RT, et al:Topical DMSO treatment for pegylated liposomaldoxorubicin-induced palmar-plantarerythrodysesthesia. Cancer ChemotherPharmacol 44:303-306, 1999.

63.

Chin SF, Tchen N, Oza AM, et al: Useof "Bag Balm" as topical treatment of palmarplantarerythrodysesthesia syndrome (PPES) inpatients receiving selected chemotherapeuticagents (abstract 1632). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol20:409a, 2001.

64.

Coleman RL, Lin WM, Miller DS, et al:Oral dexamethasone (DMS) attenuates Doxilinducedpalmar plantar erythema (PPE) in patientswith recurrent gynecologic malignancies(abstract 883). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol20:221a, 2001.

65.

Lyass O, Lotem M, Edelmann D, et al:Protective effect of amifostine (AMF) onDoxil/Caelyx-induced palmar-plantarerythrodysesthesia (PPE) in patients (pts) withadvanced cancer (abstract 2148). Proc Am SocClin Oncol 20:99b, 2001.

66.

Szumacher E, Wighton A, Franssen E,et al: Phase II study assessing the effectivenessof Biafine cream as a prophylactic agent forradiation-induced acute skin toxicity to thebreast in women undergoing radiotherapy withconcomitant CMF chemotherapy. Int J RadiatOncol Biol Phys 51:81-86, 2001.

67.

Kingsley EC: 5-Fluorouracil dermatitisprophylaxis with a nicotine patch. Ann InternMed 120:813, 1994.

68.

Peuckmann V, Fisch M, Bruera E: Potentialnovel uses of thalidomide: Focus onpalliative care. Drugs 60:273-292, 2000.

69.

Lin E, Morris JS, Ayers GD: Effect ofcelecoxib on capecitabine-induced hand-footsyndrome and antitumor activity. Oncology16(12 suppl 14):31-37, 2002.

70.

Lin E, Morris J, Chau NK, et al:Celecoxib attenuated capecitabine inducedhand-and-foot syndrome (HFS) and diarrhea andimproved time to tumor progression in metastaticcolorectal cancer (MCRC) (abstract2364). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 21:138b, 2002.

71.

Blum J, Jones S, Buzdar A, et al:Capecitabine (Xeloda) in 162 patients withpaclitaxel-pretreated MBC: Updated resultsand analysis of dose modification (abstract693). Eur J Cancer 37(suppl 6):S190,2001b.

72.

Hoff PM: Capecitabine as first-line treatmentfor metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC):Integrated results of 1201 patients (pts) from 2randomized, phase III studies. On behalf of theCapecitabine CRC Study Group (abstract 263).Ann Oncol 11(suppl 4):60, 2000.

73.

Nowacki M, Kröning H, Cervantes A, etal: Improved safety of capecitabine vs bolus 5-FU/leucovorin (LV) as adjuvant therapy forcolon cancer (the X-ACT phase III study). EurJ Cancer 1(suppl 5):S326, 2003.

74.

Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Tabernero J,et al: XELOX:Mature results of a mulitnational,phase II trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin,an effective first-line option for patients withmetastatic colorectal cancer (abstract 1023).Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:255, 2003.

75.

Patt YZ, Lin E, Leibmann J, et al:Capecitabine plus irinotecan for chemotherapynaivepatients with metastatic colorectal cancer(MCRC): US multicenter phase II trial (abstract1130). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:281, 2003.

Gedatolisib Combo With/Without Palbociclib May Be New SOC in PIK3CA Wild-Type Breast Cancer

December 21st 2025“VIKTORIA-1 is the first study to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS with PAM inhibition in patients with PIK3CA wild-type disease, all of whom received prior CDK4/6 inhibition,” said Barbara Pistilli, MD.