Current Management of Unusual Genitourinary Cancers: Part I

Often overshadowed by more common genitourinary cancers, such as prostate, testicular, and kidney cancers, penile and urethral cancers nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges for the clinician. The management

ABSTRACT: Often overshadowed by more common genitourinary cancers, such as prostate, testicular, and kidney cancers, penile and urethral cancers nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges for the clinician. The management of these cancers is slowly evolving. In the past, surgery, often extensive, was the treatment of choice. Recently, however, radiation and chemotherapy have begun to play larger roles as initial therapies, with surgery being reserved for salvage. With these modalities in their treatment armamentarium, oncologists may now be able to spare patients some of the physical and psychological sequelae that often follow surgical intervention without compromising local control and survival. Part 1 of this two-part article focuses on cancer of the penis. Part 2, which will appear in next month’s issue, discusses cancer of the urethra in both females and males. [ONCOLOGY 13(10):1347-1352, 1999]

Introduction

Penile and urethral cancers, while less common than other genitourinary cancers, such as prostate, testicular, and kidney carcinomas, nonetheless represent difficult treatment challenges. The management of these cancers is slowly evolving as radiation therapy and chemotherapy begin to play larger roles in treatment. Part 1 of this two-part article focuses on cancer of the penis. Part 2, which will appear in next month’s issue, discusses cancer of the urethra in both females and males.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Cancer of the penis is a rare disease in western countries, where it is responsible for fewer than 1% of malignancies in male patients. Worldwide, however, penile cancer constitutes a major health problem, accounting for as many as 10% to 20% of cancers in males living in Asia, Africa, and South America.[1] This cancer is virtually unknown in Jews who practice infant circumcision and is seen only rarely in Moslems who delay circumcision until the age of 3 to 13 years.

Cancer of the penis has been associated with phimosis and poor local hygiene. The human papilloma virus (HPV) may be an etiologic agent[2,3]; HPV-16, in particular, has been identified as a potential causative agent.[2] Ultraviolet radiation also appears to have carcinogenic potential for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis.[2]

Anatomy

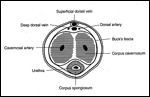

FIGURE 1

Cross-Sectional Anatomy of the Penile Shaft

The penis is composed of the corpus spongiosum and two corpora cavernosa enclosed within a fascial layer called Buck’s fascia (Figure 1). The corpus spongiosum expands distally into the glans penis, which is covered by the foreskin (prepuce).

Pathology

Over 95% of cases of penile cancer are squamous cell carcinomas (Figure 2). Bowen’s disease, or carcinoma in situ, is also seen. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a variant of carcinoma in situ. Approximately 18% of patients with acquired immune deficiency (AIDS)–related Kaposi’s sarcoma have lesions on the penis or genitalia.[2] Other sarcomas, melanomas, basal cell carcinomas, and lymphomas have been reported but are extremely rare.[ 1] A 1992 review of the literature identified 277 cases of lesions metastatic to the penis.[1]

FIGURE 2

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Penis

The incidence of lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the penis is related to histologic grade. Well-differentiated tumors have a far lower incidence of spread to the nodes than do moderately or poorly differentiated tumors.[4] Verrucous carcinoma, a variant of squamous cell carcinoma, appears to have an especially low potential for metastatic nodal spread.[5]

Routes of Spread

The skin of the penis and prepuce is drained primarily by the superficial inguinal nodes, while the glans is drained by the superficial inguinal nodes, and, along with the corpora, by the deep inguinal and iliac nodes. [6] The first site of metastasis from carcinoma of the penis is usually the inguinal nodes, with secondary involvement of the pelvic nodes. [6] Dessication of the superficial lymphatics at the base of the penis accounts for bilateral involvement.[6]

Approximately 50% of patients with cancer of the penis present with palpable inguinal nodes.[1] A course of antibiotic therapy is indicated in patients with palpable nodes, as only half will contain metastatic disease while the other half are inflamed secondary to infection of the primary tumor.[7] Conversely, approximately 20% of patients with clinically N0 inguinal nodes will be found to have metastases in these nodes if prophylactic node dissection is undertaken.[7]

The most common sites of distant metastatic disease are the lungs, liver, and bone. [1]Clinical Presentation The clinical presentation of penile cancer varies from subtle areas of induration, erythema, or warty growth to obvious extensive carcinoma.[1] The earliest symptoms include itching or burning under the foreskin and ulceration of the glans or prepuce, which can progress to a lump, mass, or nodule. With continued neglect, the lesion advances until a persistent, foul-smelling, purulent discharge exudes from beneath a frequently phimotic, nonretractable, distorted prepuce. Pain usually is not proportional to the extent of local destruction.

Ultimately, neoplastic extension along the entire glans and shaft, invasion of the corpora cavernosa, erosion of the prepuce, bleeding, fistulas, or total destruction of the penis may occur. Occasionally, inguinal ulceration is the initial complaint because of tumor concealed in a phimotic preputial sac. [1]

Diagnostic and Staging Studies

TABLE 1

TNM Staging of Cancer of the Penis

The work-up for carcinoma of the penis begins with direct examination and palpation of the penis and inguinal nodes. Cancer of the penis can infiltrate deeply into local tissues. Ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the penis may be useful in delineating the degree of local infiltration.[8]

A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the pelvis and abdomen can help assess the pelvic and para-aortic nodes. A chest x-ray should be obtained in all patients, and a bone scan should be performed when clinically appropriate. A lymphangiogram is not warranted, as it appears to add little information beyond that provided by clinical examination[1] and CT.

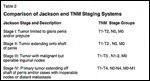

Staging

The TNM staging system for penile cancer is shown in Table 1. In the literature, the Jackson system is also used extensively, although it lacks the precision of the TNM system. Table 2 compares the two staging systems.

Treatment

Surgery

Surgery for treatment of carcinoma of the penis has ranged from circumcision and local excision to radical penectomy, depending on the extent of the lesion. Most authors recommend a 1.5- to 2-cm margin of resection to prevent local recurrence.[9-11] However, a Moh’s micrographic surgical technique has been described; this procedure may offer a less deforming alternative in selected patients and local control rates up to 86%.[11] Erythroplasia of Queyrat usually is managed by circumcision and topical fluorouracil. Bowen’s disease can be managed by local excision or Moh’s surgery. [2,11]

TABLE 2

Comparison of Jackson and TNM Staging Systems

Most relapses occur within the first 12 to 18 months after penectomy.[12] Thus, close follow-up of these patients is important. Montie[12] recommends performing a physical examination of the inguinal nodes monthly for the first 6 months, bimonthly for the next 6 months, and then quarterly for the next year for higher-risk individuals (ie, those with poorly differentiated histology or invasion of the glans or corpus cavernosum). Inguinal CT scans are obtained every 3 to 4 months for the first year.

For patients who develop penile recurrence after initial partial penectomy, further surgical salvage may be possible.[12] Disease that recurs in the urethra is particularly worrisome. Such disease tends to grow quickly through the corpus spongiosum. When faced with this situation, the surgeon should consider resecting the entire urethra and possibly performing an anterior exenteration.[13]

Management of the Regional Nodes

As mentioned above, primary drainage of the penis is to the superficial and deep inguinal nodes. Secondary drainage is to the iliac nodes, although direct drainage to these nodes can occur.[14] Also as previously mentioned, roughly 50% of patients with carcinoma of the penis present with palpable inguinal lymph nodes.

Patients with persistent palpable adenopathy after antibiotic therapy should undergo biopsy, and if positive, should proceed to dissection. Patients with suspicious pelvic or para-aortic nodes on CT should undergo initial needle biopsy of these nodes.

Clinically N0 Patients-Although there is no dispute in the literature regarding the management of patients with clinically positive inguinal nodes (especially persistently palpable nodes after a trial of antibiotics), considerable controversy still remains regarding the treatment of the clinically N0 patient, in whom prophylactic dissection will reveal an occult metastatic rate of approximately 20%. The controversy centers on whether or not patients who are treated with a “wait and watch” policy regarding the groin will experience a decrease in survival, as compared with those treated with immediate prophylactic dissection. Some authors have reported a decrease in survival in patients who are managed with observation only.[4,15-17]

The main objection to prophylactic groin dissection is its reported high incidence of morbidity. A 30% incidence of major complications, such as flap necrosis, wound infection, seroma, lymphocele, and persistent leg edema, and a 3% mortality have been reported. [4] However, morbidity and mortality may not be as high in patients treated with prophylactic dissection as in those who undergo therapeutic dissection for involved nodes.

Lymph node dissections usually consist of an inguinal lymphadenectomy. If the groin nodes are positive, an iliac dissection is usually performed.[17] In an attempt to decrease the morbidity of these procedures, Catalona[18] has reported using a modified lymphadenectomy approach in which the saphenous vein is preserved.

A 1977 report by Cabanas[19] suggesting that prophylactic sentinel node biopsy may guide the management of N0 cases has been refuted by other investigators.[20-22] The location of the so-called sentinel node may actually vary, which may explain the confusion.[23]

Most authors who advocate prophylactic inguinal lymph node dissection[5,16,17] recommend doing so in patients with Jackson stage II or poorly differentiated tumors, as the incidence of positive nodes in these cases is greater than in well-differentiated, stage I tumors.

Other authors advocate a wait and watch policy for compliant N0 patients. Proponents of this approach cite the good surgical salvage rates achieved in these patients.[19,20] A 1993 study from India[24] involving a large number of patients (423) treated at one institution showed similar 5-year survival rates in patients treated with prophylactic groin dissection, initial biopsy, or a wait and watch strategy. As stressed by these authors, patient compliance with follow-up is mandatory.

There is a scarcity of information regarding prophylactic radiation to the groins in lieu of observation or prophylactic lymph node dissection. Although it would appear logical that irradiating both groins with 5,000 cGy over 5 weeks would control greater than 90% of subclinical disease,[25] the few reports in the literature contain very small numbers of patients with penile cancer.

Current Recommendations-Compliant patients with well-differentiated tumors confined to the glans who are clinically N0 can be treated with close observation of the groin. Management of patients with higher-grade and/or more extensive lesions with prophylactic lymphadenectomy is still controversial. Prophylactic groin radiation in lieu of prophylactic dissection or observation is a logical alternative but is yet unproven in this situation.

The survival of patients with carcinoma of the penis depends on the status of the lymph nodes. Patients with tumor-free nodes have an excellent overall cure rate of 85% to 90%.[26] Most series show a substantial decrease in 5-year survival rate-to less than 50%-in patients with involved inguinal nodes, especially those presenting with synchronous metastases or with fixed, multiple, or bilateral nodes. [6]

In patients with histologically confirmed involved inguinal nodes, many authors recommend a dissection of the pelvic nodes as well,[7,17,24] although it is acknowledged that such patients have a dismal prognosis, ranging from 9% to 20%,[6,19,26] with death occurring from metastatic disease.

Radiation Therapy

Because of the obvious psychosocial and physical morbidity caused by partial or total penectomy, radiation therapy has been used as a viable alternative to surgery in selected patients in order to preserve normal structure and function of the penis. Both external-beam and brachytherapy techniques have been studied.[20,26-34]

Circumcision is generally recommended before radiation therapy is initiated.[26,33,34] This allows for further evaluation of tumor extent and minimizes morbidity associated with radiation, such as swelling, irritation, moist desquamation, and secondary infection. In addition, circumcision eliminates phimosis, which may also result from radiation.[33]

External-Beam Radiation-For external-beam treatment, a variety of dose-fractionation schedules have been reported, but the most widely accepted schedule for small lesions is 40 Gy in 20 fractions over 4 weeks to the entire shaft of the penis; megavoltage beams (low-energy photons), delivered by parallel opposed ports, are used.[7,20] The primary lesion and margins are then boosted with another ten 2-Gy fractions. In general, radiation therapy (either external-beam radiation or brachytherapy) is not advised for lesions greater than approximately 4 cm.[7,20,28,34]

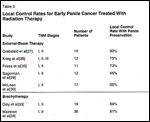

TABLE 3

Local Control Rates for Early Penile Cancer Treated With Radiation Therapy

As shown in Table 3, the local control rate with external-beam therapy varies from about 60% to 90%[20,27-30] and averages about 75%.[7] Surgical salvage can be performed in patients when primary radiotherapy proves ineffective.[28,29]

Acute reactions of skin irritation, desquamation, soreness, and swelling are common, but self-limited, side effects of radiation. The major long-term complication appears to be urethral stricture or stenosis, which occurs in 16% to 49% of patients.[27,28,30] However, usually this is easily managed by simple dilatation. Telangiectasia is noted in a significant number of cases[27] but is not bothersome.

Penile necrosis is an uncommon complication, which usually develops only in patients with very large tumors treated with higher than recommended radiation doses. A majority of patients, up to 90% of those treated, will maintain sexual potency.[27,28]

Brachytherapy-Two brachytherapy techniques have been used in patients with penile cancer. In the first, a radioactive mold is placed over the penis and worn by the patient[32] 12 hours daily for 1 week[26]; this radioactive mold delivers a 60-Gy dose to the tumor and 50 Gy to the urethra. Interstitial therapy also has been employed; iridium-192 is the isotope now used most commonly.

Circumcision is recommended prior to brachytherapy, and tumors should be £ 4 cm or without major invasion (< 1 cm) into the corpora cavernosa.[26,33,34] Local control rates (with preservation of the penis) for interstitial brachytherapy have ranged from 58% to 89% (Table 3).[26,33,34]

Complications of brachytherapy are similar to those reported with external-beam radiation therapy. Urethral stenosis has been reported in 0% to 43% of patients who undergo brachytherapy.[26,33,34] Sexual potency, however, appears to be preserved.[33]

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in carcinoma of the penis is difficult to evaluate, as most published studies have had small numbers of patients, and patient selection factors and extents of disease treated have varied. Variations in chemotherapy doses and schedules have occurred even in the same series.

The most commonly studied drugs in penile cancer have been cisplatin (Platinol), bleomycin (Blenoxane), methotrexate, and fluorouracil. The response rates for cisplatin alone have ranged from 15% to 23%.[35,36]

Two reports have shown that combining cisplatin and fluorouracil creates some response; however, these studies are difficult to assess because of varying treatment parameters.[37,38]

Finally, bleomycin alone, with radiation, or in combination with vincristine and methotrexate has clearly shown activity, which approached 45% in one report.[35]

Currently, the role of chemotherapy remains investigational. Three settings in which this modality may be beneficial are in the presence of overt metastatic disease, in the neoadjuvant setting to attempt to render unresectable disease resectable, or in the setting of pathologically proven lymph node metastases.

References:

1. Burgers J, Badalament R, Drago J: Penile cancer: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urol Clin North Am 19:247-256, 1992.

2. Grossman H: Premalignant carcinomas of the penis and scrotum. Urol Clin North Am 19:221-226, 1992.

3. McCance D, Kopan R, Fuchs E, et al: Human papillomavirus type 16 alters human epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:7169-7173, 1988.

4. Fraley E, Zhang G, Manievel C, et al: The role of ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy and significance of histological differentiation in treatment of carcinoma of the penis. J Urol 142:1478-1482, 1989.

5. Seixas ACL, Ornellas AA, Marota A: Verrucous carcinoma of the penis: Retrospective analysis of 32 cases. J Urol 152:1476-1479, 1994.

6. Srinivas V, Moise J, Herr H, et al: Penile cancer: Relation of extent of nodal metastasis to survival. J Urol 137:880-882, 1987.

7. Jones W, Hamers H, Bogaert WVD: Penis cancer: A review by the Joint Radiotherapy Committee of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Genitourinary and Radiotherapy Groups. J Surg Oncol 40:227-231, 1989.

8. Vapnek J, Hricak H, Carroll P: Recent advances in imaging studies for staging of penile and urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 19:257-266, 1992.

9. Bissada N: Conservative extirpative treatment of cancer of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 19:283-290, 1992.

10. Das S: Penile amputations for the management of primary carcinoma of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 19:277-282, 1992.

11. Mohs F, Snow S, Larson P: Mohs micrographic surgery for penile tumors. Urol Clin North Am 19:291-304, 1992.

12. Montie JE: Follow-up after penectomy for penile cancer. Urol Clin North Am 21:725-727, 1994.

13. Lerner SE, Jones JG, Fleischman J: Management of recurrent penile cancer following partial or total penectomy. Urol Clin North Am 21:729-737, 1994.

14. Dewire D, Lepor H: Anatomic considerations of the penis and its lymphatic drainage. Urol Clin North Am 19:211-219, 1992.

15. Johnson D, Lo R: Management of regional lymph nodes in penile carcinoma. Urology 24:308-311, 1984.

16. Mukamel E, DeKernion J: Early vs delayed lymph-node dissection versus no lymph-node dissection in carcinoma of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 14:707-711, 1987.

17. McDougal W, Kirchner F, Edwards R, et al: Treatment of carcinoma of the penis: The case for primary lymphadenectomy. J Urol 136:38-41, 1986.

18. Catalona W: Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with preservation of saphenous veins: Technique and preliminary results. J Urol 140:836, 1988.

19. Cabanas R: An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer 39:456-466, 1977.

20. Fossa S, Hall K, Johannessen N, et al: Cancer of the penis experience at the Norwegian Radium Hospital 1974-1985. Eur Urol 13:372-377, 1987.

21. Perinetti E, Crane D, Catalona W: Unreliability of sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging penile carcinoma. J Urol 124:734-735, 1980.

22. Wespes E, Simon J, Schulman C: Cabanas approach: Is sentinel node biopsy reliable for staging penile carcinoma? Urology 28:278-279, 1986.

23. Cabanas R: Anatomy and biopsy of sentinel lymph nodes. Urol Clin North Am 19:267-276, 1992.

24. Ravi R: Prophylactic lymphadenectomy vs observation vs inguinal biopsy in node-negative patients with invasive carcinoma of the penis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 23:53-58, 1993.

25. Lee R, McCollough M, Menderhall W, et al: Elective inguinal node irradiation for pelvic carcinomas. Cancer 72:2058-2065, 1993

26. Gerbaulet A, Lambin P: Radiation therapy of cancer of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 19:325-332, 1992.

27. Grabstald H, Kelley C: Radiation therapy of penile cancer six to ten year follow-up. Urology 15:575-576, 1980.

28. Krieg R, Luk K: Carcinoma of the penis: Review of cases treated by surgery and radiation therapy 1960-1970. Urology 18:149-154, 1981.

29. Sagerman R, Yu W, Chung C, et al: External-beam irradiation of carcinoma of the penis. Radiology 152:183-185, 1984.

30. McLean M, Ahmed MA, Warde P, et al: The results of primary radiation therapy in the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 25:623-628, 1993.

31. Sarin R, Norman AR, Steel GG, et al: Treatment results and prognostic factors in 101 men treated for squamous carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38:713-722, 1997.

32. El-Demiry M, Oliver R, Hope-Stone H, et al: Reappraisal of the role of radiotherapy and surgery in the management of carcinoma of the penis. Br J Urol 56:724-728, 1984.

33. Daly N, Douchez J, Combes P: Treatment of carcinoma of the penis by iridium 192 wire implant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 8:1239-1243, 1982.

34. Mazeron J, Langlois D, Lobo P, et al: Interstitial radiation therapy for carcinoma of the penis using iridium 192 wires: The Henri Mondor experience (1970-1979). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 10:1891-1895, 1984.

35. Eisenberger M: Chemotherapy for carcinomas of the penis and urethra. Urol Clin North Am 19:333-338, 1992.

36. Gagliano R, Blumenstein B, Crawford E, et al: Cis-diamminedi-chloroplatinum in the treatment of advanced epidermoid carcinoma of the penis: A Southwest Oncology Group study. J Urol 141:66-67, 1989.

37. Shammas F, Ous S, Fossa S: Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in advanced cancer of the penis. J Urol 147:630-632, 1992.

38. Hussein A, Benedetto P, Sridhar K: Chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for penile and urethral squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer 65:433-438, 1990.