The Evolving Paradigm of Adult Cancer Survivor Care

Current US statistics on cancer reveal that more than 11 million cancer survivors live among us today, and that number is expected to double by 2050.[1,2] One important contributing trend has been a fall in cancer deaths driven by earlier detection and improved treatment. Deaths resulting from cancer declined from 206.7 per 100,000 population in 1980 to 185.7 per 100,000 in 2004. Meanwhile, the adjusted 5-year survival rate for cancers overall increased from 50% to 66% between 1975–1977 and 1996–2003,[3] and these statistics speak only to relatively short-term survival. About 1 in every 7 survivors today received their diagnosis more than 20 years ago.[4]

ABSTRACT: As a result of earlier diagnosis and improved treatment, the number of cancer survivors is steadily increasing, with over 11 million in the US today. These survivors face a multitude of long-term and late effects as a result of their cancer and its treatment. It is increasingly recognized that this group has complex and ongoing needs for medical care education, surveillance, screening, and support. Many organizations have helped to advance survivorship care; key among them are the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, the Institute of Medicine, the Lance Armstrong Foundation, and the Office of Cancer Survivorship of the National Cancer Institute. Important reports have defined goals of care; identified interventions to improve outcomes among survivors; and recognized the need for posttreatment surveillance, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and continued research in all of these areas. With these advances, survivorship care is emerging as a distinct component of the continuum of care in oncology.

Current US statistics on cancer reveal that more than 11 million cancer survivors live among us today, and that number is expected to double by 2050.[1,2] One important contributing trend has been a fall in cancer deaths driven by earlier detection and improved treatment. Deaths resulting from cancer declined from 206.7 per 100,000 population in 1980 to 185.7 per 100,000 in 2004. Meanwhile, the adjusted 5-year survival rate for cancers overall increased from 50% to 66% between 1975–1977 and 1996–2003,[3] and these statistics speak only to relatively short-term survival. About 1 in every 7 survivors today received their diagnosis more than 20 years ago.[4]

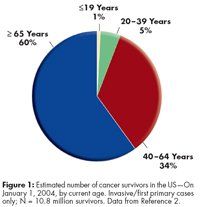

A second trend is related to changes in the age distribution of our population. In 1990, approximately 40% of the population was younger than age 35. By 2010, the majority of the population will be age 45 or older. Cancer occurs more commonly among older adults, and with greater numbers of people receiving cancer diagnoses and treatment, the percentage of survivors in this age-group has increased. In fact, 60% of cancer survivors are aged 65 years or older (see Figure 1).

For these 11 million survivors, cancer is considered a chronic disease, in which long-term and

late effects of treatment are overlaid with the potential for exacerbations and remissions. These events can be life-altering-both for survivors and for their families and caregivers. Most cancer survivors do very well once cancer treatment has ended, but there are potential sequelae that include impaired physical function, reduced fertility, neurocognitive deficits, chronic symptoms such as pain and fatigue, elevated risks of second malignancies and other treatment-induced conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis), and psychosocial morbidity and the fear of recurrence.[5–7] Compounding these issues may be concerns about employment and health insurance coverage.[8–10]

It is increasingly recognized that cancer survivors have complex and ongoing needs for education, surveillance, screening, and support. The medical community must consider plans of care that encompass follow-up and monitoring for effects of cancer treatment; surveillance for recurrent or new cancers; and health promotion strategies (see Figure 2).[11–13] Clearly, as Julia Rowland, PhD, the director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Office of Cancer Survivorship (OCS), states, “disease-free does not mean being free of your disease.”[13]

History of the Survivorship Movement

The initial impetus for a cancer survivorship movement was the increasing survival of patients

with a disease that historically had been rapidly and almost universally fatal. Gains achieved have been largely due to improvements in screening, early detection, and treatment; better control of adverse effects (enabling receipt of higher doses of therapies more likely to be effective); and the advent of targeted therapies.[4]

Not surprisingly, survivors and their families and caregivers spearheaded many early efforts to improve outcomes after a cancer diagnosis, and continue to be active today. Nationally, private and governmental entities further advanced the survivorship movement (see Figure 3). Their research, recommendations, and collaboration have given rise to the evolving paradigm of health care for cancer survivors seen today. In particular, these activities have been critical in uncovering deficits in care, leading to new proposed models of care, and identifying key areas for research.

Cancer Care

A private, national nonprofit organization founded in 1944, CancerCare provides free professional support services to anyone affected by cancer. CancerCare services include telephone as well as web-based education for both patients and professionals, and its focus now includes support for survivors.[14]

American Cancer Society

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is the oldest voluntary health agency dedicated to conquering cancer through research, education, advocacy, and service. Development and distribution of patient education materials has been a major activity since its inception in 1946. The first Survivor Bill of Rights was published by the ACS in 1988. “Reach for Recovery” and “I Can Cope” are examples of well-established ACS programs available through 13 divisions and 3,400 local ACS offices nationwide.[15] The ACS reaches out through its online Cancer Survivors Network, “created by and for cancer survivors and their loved ones.”[16]

The Wellness Community

The Wellness Community, an international nonprofit organization, was founded in California in 1982 by Harold Benjamin, PhD, as a result of his wife’s experience with breast cancer.[17] His interest in the psychological and social impact of cancer led to the development of the Patient Active Concept, in which care is built around the idea of community. Services include networks providing web-based access to support groups and local support offices with many additional resources and programs. As explained on The Wellness Community’s web site, “Through participation in professionally led support groups, educational workshops, nutrition and exercise programs, and mind/body classes, people affected by cancer learn vital skills that enable them to regain control, reduce isolation, and restore hope regardless of the stage of their disease.” There are 24 Wellness Communities in the US, 56 satellite and off-site programs, 2 centers elsewhere (in Tel Aviv and Tokyo), 3 centers now being planned, and the online Virtual Wellness Community.

National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship

One of the earliest organizations to address advocacy issues was the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), founded in 1986 by a group of cancer survivors and health professionals. The NCCS is the oldest survivor-led cancer advocacy organization in the US. Founding members were pioneers advocating for health-care coverage and increased access to new treatments for cancer patients.

Importantly, NCCS broadly defines the period of cancer survivorship as starting “from the time of its discovery and [extending] for the balance of life.”[13] It does not differentiate patients in active treatment from those who are disease-free or who have end-stage disease, thus helping to focus on the activities, facilities, personnel, and research needed to improve support for all individuals following a cancer diagnosis.[18]

The NCCS advocates for systemic change at the national level to improve cancer care. Its Cancer Advocacy Now legislative advocacy network mobilizes constituents on cancer-related issues. The NCCN is also committed to patient education; it offers the Cancer Survival Toolbox, a free online audio program covering basic skills related to challenges survivors face (eg, finding information, making decisions, and paying for care) and Cancer Keys to Survivorship, a free educational program that addresses additional skills needed after a cancer diagnosis (eg, communicating with providers, self-advocacy, handling fatigue, employment rights, and health insurance).

Cancer Leadership Council

The Cancer Leadership Council was formed in 1993 by eight cancer patient organizations. It recently expanded to represent 33 additional cancer patient organizations, professional societies, and research organizations. The Council provides collective support for changing governmental policies, promotes health care reform, and advocates for cancer survivors.[12] These private activities have stimulated the development of a number of governmental reports and initiatives that center the focus on cancer survivors.

Lance Armstrong Foundation

One of the most active private foundations in cancer survivorship is the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF), established in 1997.[19] LAF’s agenda includes improving quality of life for survivors.

The foundation’s early efforts focused on raising funds to support cancer research. In 2000 LAF provided funds for cancer survivorship programs at two medical centers. In 2003 the foundation initiated support of community programs and launched LiveStrong.org as an online resource for cancer survivors. In 2004 LAF introduced the LIVESTRONG wristband and Wear Yellow LIVESTRONG campaigns and, in collaboration with CancerCare, LIVESTRONG SurvivorCare, a program dedicated to providing information and support to cancer patients and their families starting from the moment of diagnosis, with emphasis on the post-treatment period. In the same year, LAF and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention jointly released the National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship.[19]

Another mechanism by which LAF promotes improved survivorship care is the LIVESTRONG Survivorship Centers of Excellence Network, initiated in 2000. The cancer centers and their community affiliates in this network are selected through a competitive review process and are eligible to receive funding from the LAF to develop and implement programs specifically for survivors. The network grew from 2 centers at its inception to 7 centers and 21 community affiliates in 2005.

Through LAF, a variety of grass-roots organizations have raised millions of dollars to support the needs of cancer survivors. In addition, LAF provides educational support via patient tools and brochures aimed at reaching underserved populations through the Living After Cancer Treatment series.[19]

Office of Cancer Survivorship

The Office of Cancer Survivorship (OCS) was created by the National Cancer Institute in 1996 in response to several important reports on survivorship and recognition of the increasing number of patients who are long-term survivors after primary treatment, and the challenges they face.[7,20] The main goal of the OCS is to promote evidence-based, comprehensive, compassionate, and coordinated care throughout the cancer experience by supporting research on short- and long-term effects of cancer and cancer treatment.[13] As such, this office plays a central role in filling in the gaps in knowledge surrounding survivorship.

Survivorship Reports

Since the mid 1990s, several reports have been released that have catalyzed action for survivorship research and care. These reports have better clarified survivors’ diverse needs, highlighted shortcomings in current care, documented the roles of various stakeholders, outlined specific strategies and necessary actions to be undertaken, and identified areas requiring further research.

Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care: Access, Advocacy, Action & Accountability

In 1996, the NCCS issued a groundbreaking report that, for the first time, addressed the quality of cancer care from the perspective of patients.[21] This seminal report, Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care: Access, Advocacy, Action & Accountability, addresses mechanisms of health care coverage, measurement of and barriers to quality care, long-term and late effects, and psychosocial challenges patients face, among other topics-all issues that remain relevant and important in survivorship care more than a decade later.

Ensuring Quality Cancer Care

In 1997, the National Cancer Policy Board, a division of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), issued Ensuring Quality Cancer Care.[22] This report, drafted by consumers, health care providers, and researchers, explores the state of the cancer care system, the definition and measurement of quality care, problems in care and steps for addressing them, approaches for learning more about the quality of care, and approaches for overcoming barriers to quality care. Combined with the NCCS report, this report influenced the decision by Richard Klausner, MD, director of the NCI, to establish the OCS in 1996.[13]

Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance

Acknowledging that individuals are forever changed by a cancer diagnosis, the 2003/2004 annual report of the President’s Cancer Panel, Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance, focuses on addressing the diverse needs of this population to improve their well-being.[23] The report draws in large part on testimony from survivors. Among its many recommendations for survivorship care, the report calls for providing patients with a record of care and a follow-up care plan, procedures for better informing patients of their legal and regulatory protections, national efforts to raise awareness of survivorship issues, a central repository for evidence on late and long-term effects, evaluation of the potential role of specialized follow-up clinics, incorporation of survivorship into the core curricula of health care education, routine inclusion of psychosocial services as part of cancer care, and adequate health insurance coverage of prostheses, psychosocial services, and follow-up care.

National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the LAF jointly released the National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies in 2004, spearheading a public effort to comprehensively address the needs and concerns of cancer survivors.[24] The plan represents the combined efforts of nearly 100 experts in public health and cancer survivorship. It identifies and prioritizes 23 needs in the realm of survivorship and suggests approaches for addressing these needs in four core public health domains: surveillance and applied research; communication, education, and training; programs, policies, and infrastructure; and access to quality care and services. This plan helped advance the survivorship movement by delineating how coordinated public health initiatives can be used to ultimately improve the well-being and quality of life of cancer survivors.

Assessing Progress, Advancing Change

The 2005/2006 annual report of the President’s Cancer Panel, Assessing Progress, Advancing Change, revisits three survivorship issues identified in the 2003/2004 report: provision of treatment summaries and follow-up care plans to patients, expansion of research on adolescents and young adults with cancer, and improvement of insurance and access for cancer survivors.[25]

For each of these issues, this report details the progress made, identifies the main priorities for the next 2 years, and-importantly-documents commitments of stakeholders to achieving these objectives. The panel concludes that although survivorship care in these areas has improved, several overarching issues-fiscal constraints and deficits in health care coverage, public education and communication, and coordination-must be contended with in order to enable further progress.

From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition

In 2006, the IOM released a major report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, that focuses on survivors of adult cancers after primary treatment.[1] It aims to “raise awareness of the consequences of cancer and its treatment,” to “define quality health care for cancer survivors and identify strategies to achieve it,” and to “improve the quality of life of cancer survivors through policies to ensure their access to psychosocial services, fair employment practices, and health insurance.”[1]

This comprehensive report includes 10 recommendations for care and research. (See box, “Ten IOM Recommendations for Improving the Health Care and Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors.”)[1] It also identifies four components of survivorship care that are essential to ensure quality: 1) prevention of recurrent and new cancers and late-effects management; 2) surveillance for potential recurrence or second cancers and assessment of medical and psychosocial late effects; 3) intervention for consequences of cancer and its treatment; and 4) coordination of care between specialists and the primary care provider in an effort to meet all of the health-care needs of cancer survivors.[1]

Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs

The IOM issued a second critical report on survivorship in 2007, Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, which explores inconsistencies in psychosocial care across different cancer settings.[26] It outlines a framework for providing effective psychosocial care to identify needs of cancer survivors, provide resource links for patients and families, identify support for managing illness, coordinate psychosocial and biomedical health care, and monitor the effectiveness of these services. This report is noteworthy in that it focuses the spotlight on an often overlooked aspect of survivorship care.

Deficits and Recommended Changes in Cancer Care

Despite encouraging gains in survivorship care, there is substantial room for improvement. One shortcoming of this care has been an emphasis on the treatment and immediate posttreatment periods, but the focus is now shifting from managing patients’ acute issues to addressing their long-term health needs.[5,6,27] These long-term health needs will include some that are related to the cancer diagnosis and others that are not. For example, compared with their counterparts in the general population, survivors have similar levels of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors in terms of smoking, diet, physical activity, and body weight.[28]

Given survivors’ many health needs, providers also may focus on certain needs to the detriment of others. Care should include ongoing surveillance, early diagnosis and treatment of physiological late effects, and support for psychosocial challenges, tailored to each patient’s unique history-type of cancer, treatments received, genetic risks, and comorbidities. The following are cornerstones of survivorship care:

• Monitor physical health. Periodic assessment can detect signs or symptoms of recurrence, long-term or late effects, new primaries, and comorbidities.[6] Assessment should include a comprehensive medical history with a cancer-focused review of systems. (See sidebar, “Review of Systems for Cancer Survivors.”)

• Assess psychosocial well-being. Assessment of survivors’ psychosocial well-being should be a part of routine follow-up care.[23,26,27] Fully one-third of cancer survivors experience psychosocial distress and would benefit from early intervention.[26,29]

• Address disease prevention and health promotion. Follow-up care is an opportunity to address health risks amenable to intervention. Furthermore, there is increasing recognition that a cancer diagnosis provides a “teachable moment” in which patients, confronted by a life-threatening illness, are more motivated and receptive to changes to improve their health.[5]

• Follow up on risks of new cancers. Some survivors may have elevated risks of new primary cancers related to their initial cancer and its treatment or to hereditary factors.[5,30,31] This group may benefit from receiving counseling and screening.

• Provide information and support. Survivors need information and support on wide-ranging topics, some of which are not directly medical (eg, patients may look to providers for guidance on legal protections regarding employment and health insurance).[8–10]

Survivorship care is a multidisciplinary effort,[32] but inadequate communication among providers can compromise the quality of this care. Over the course of their lives, survivors may consult generalist and specialist physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals (eg, geneticists, nutritionists, physical therapists, psychologists), which can have the unintended effect of fragmentation of care. Good communication among all parties involved is important for ensuring that survivors’ needs are being met. Treatment summaries and survivorship care plans have the potential to improve follow-up care through better communication.

Making survivorship topics part of basic and continuing medical education curricula may help to ensure that clinicians routinely address these aspects of care.[32] An example of such an initiative is the NCI-funded Survivorship Education for Quality

Cancer Care project.[33] Professionals attend an intensive workshop on survivorship, select goals to implement at their institutions, and complete follow-up questionnaires over the next 18 months to assess their progress. Thus far, 102 two-person teams from cancer settings across the country have been trained.

The median number of new patients seen annually at the participating institutions was 1,375, illustrating how many patients may ultimately benefit from this training. Some 34% of the teams’ goals have focused on educating patients, family, and professionals; 10% have focused on developing care plans; and 12% have focused on outcomes, for example, the distribution of care plans to professionals. Examples of goals that have been successfully implemented include an 8-week program for survivors aged 15–21 years on health, wellness, and cancer prevention, and a project to provide printed information on cancer survivorship to all patients discharged after treatment.

Deficits seen in the standard medical care of patient subpopulations also exist in survivorship care. For example, racial and ethnic disparities in the African-American and Hispanic populations (eg, difficulties in access to care, language barriers) result in delayed diagnosis and treatment, decreasing survival. Psychosocial and financial concerns are also ignored in these populations. The NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences conducts cancer survivorship research among minority and medically underserved groups, as does the American Association for Cancer Research, which in 2007 hosted its first conference to share data on how cancer affects different racial, ethnic, and medically underserved groups.[34,35]

Treatment Summaries and Survivorship Care Plans

Gaps in communication between health-care providers are a major impediment to necessary coordination of care after treatment. To address this issue, the IOM has recommended that providers complete two reports for patients undergoing cancer treatment: a treatment summary and a survivorship care plan.

The treatment summary details type of treatment received, chemotherapy and radiation doses, and any complications or sensitivities the patient may have experienced. It should be provided to each patient at the end of treatment and be available for use in follow-up care by oncologists and primary care providers.

The survivorship care plan includes a disease-specific plan for follow-up with screening recommendations and information about possible late effects tailored to each patient.[36] It needs to be shared with primary care providers and with patients. Survivorship care is based on the plan, coordinated by the physician in collaboration with the patient, and provides education to help survivors identify and cope with survivorship needs and avoid preventable problems.[37,38]

Certain issues must be resolved for successful adoption of survivorship care planning, such as defining the content of the plans, determining the roles of various health care providers, allocating time to complete the plans, and procuring reimbursement.[39] A significant barrier to developing adult survivor plans is the lack of follow-up guidelines in this age-group. Pediatric cancer follow-up guidelines, published through the Children’s Oncology Group, provide a framework for long-term follow-up clinics in pediatric settings.[40] Professional organizations, such as the IOM and American Society of Clinical Oncology, are involved in efforts to increase adoption of survivorship care planning.[39]

Current Models of Survivorship Care

The recognition that survivorship care for cancer patients is a new development in medical care has stimulated the creation and evaluation of different models for providing this care.[38,41] These models vary depending on resources and whether a program provides a one-time consultation or ongoing care.

Survivorship care is evolving into three different models, according to Oeffinger and McCabe.[41] The first is a consultative model, in which patients are referred for a one-time consultation with a survivor-program staff member. A plan of care is provided to the patient, with referrals to the appropriate specialties (eg, psychiatric professional or social worker for psychosocial support, nutritionist for dietary concerns, etc). Ongoing care continues to be provided by the treating oncologist.

The second model of care includes a clinic directed by a nurse-practitioner, that operates as an extension of the oncology treatment team. Using an established plan of care, the NP assesses the survivor for recurrence and late effects of treatment, provides screening recommendations, and reviews health promotion strategies. Patients may be transitioned to the patient’s primary care physician when appropriate per guidelines. This model is the most cost-effective one, owing to minimal personnel costs, and it offers the ability to provide ongoing specialized follow-up care to survivors.

Finally, the third model of care is a specialized, multidisciplinary survivorship clinic. This model is being evaluated in large academic settings in which multiple specialists practice together in one comprehensive clinic. Therefore, the patient could see two or three different specialists, as needed, within a single visit. This is the most expensive model of care and is modeled primarily by the pediatric long-term follow-up programs. Using this model will require clear responsibility for reimbursement by insurance carriers. Research evaluating these three models is needed to assess which are best for specific survivors and which work in the community versus academic centers.

The Role of Nurses

Regardless of the model of care, nurses continue to make substantial contributions to improving survivorship care, not only through direct patient care, but also through ongoing professional development and certification, programs, publications, and research in the field.[42] In fact, meeting the needs of the growing survivor population will likely require more nurses with advanced training in oncology.[32]

At a Cancer Survivorship Nursing Stakeholder Meeting, held at the National Academy of Sciences, key nursing organizations endorsed an expanded role for nurses in delivering survivorship care and explored strategies for engaging this group in efforts to improve outcomes for survivors.[43] One example of a way in which nurses might meet this objective is through participation in survivorship planning. In a recent focus group study, nurses noted the lack of a formalized approach to follow-up care and expressed a willingness to actively participate in the creation and implementation of survivorship plans.[39] Another example of how nurses can assume a greater role is through nurse-led initiatives and training programs aimed at improving care, such as the Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care project.[33]

Research Directions

Most of what is known about survivors’ needs is based on descriptive studies conducted over the limited time between diagnosis and end of treatment. Clearly, additional research is needed to better define and address posttreatment challenges. Goals of survivorship research are to identify long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment, and to develop interventions to prevent, reduce, or eliminate them and thereby improve physical, psychosocial, and spiritual outcomes for cancer survivors and their families.

The OCS, under the auspices of the NCI, has identified key areas for cancer survivorship research, including chronic and late effects and their treatment; interventions; healthy lifestyle and behaviors; benefit finding and posttraumatic growth; and impact of cancer on the family.[44] In addition, initiatives should be directed to minority and underserved cancer survivors, innovative approaches for cancer control in cancer centers, and potential benefits of physical activity.

Conclusions

Survivorship care is gaining recognition as a distinct period of oncology care, but opportunities still exist for improving the quality of this care. The need to deliver comprehensive and consistent care to our ever-growing number of cancer survivors is urgent.[13,40] Ensuring their overall well-being will require greater attention to long-term and late effects of treatment, increased disease prevention and health promotion efforts, further education of health care professionals, and improved communication through the use of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans. Health care providers, patients, advocates, policy makers, and program planners now have access to resources for survivorship information. (See box, “Cancer Survivorship Web Resources.”) Ongoing research will be critical to filling in the gaps in this knowledge base.

“Ten IOM Recommendations for Improving the Health Care and Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors”

1. Health care providers, patient advocates, and other stakeholders should work to raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care.

2. Patients completing primary treatment should be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan that is clearly and effectively explained. This “Survivorship Care Plan” should be written by the principal provider(s) who coordinated oncology treatment. This service should be reimbursed by third-party payers of health care.

3. Health care providers should use systematically developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. Existing guidelines should be refined and new evidence-based guidelines should be developed through public-and-private-sector efforts.

4. Quality of survivorship care measures should be developed through public/private partnerships and quality assurance programs implemented by health systems to monitor and improve the care that all survivors receive.

5. CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services], NCI [National Cancer Institute], the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and other qualified organizations should support demonstration programs to test models of coordinated, interdisciplinary survivorship care in diverse communities and across systems of care.

6. Congress should support the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], other collaborating institutions, and the states in developing comprehensive cancer control plans that include consideration of survivorship care, and promoting the implementation, evaluation, and refinement of existing state cancer control plans.

7. The NCI, professional associations, and voluntary organizations should expand and coordinate their efforts to provide educational opportunities to health care providers to equip them to address the health care and quality of life issues facing cancer survivors.

8. Employers, legal advocates, health care providers, sponsors of support services, and government agencies should act to eliminate discrimination and minimize adverse effects of cancer on employment, while supporting cancer survivors with short- and long-term limitations in ability to work.

9. Federal and state policymakers should act to ensure that all cancer survivors have access to adequate and affordable health insurance. Insurers and payers of health care should recognize survivorship care as an essential part of cancer care and design benefits, payment policies, and reimbursement mechanisms to facilitate coverage for evidence-based aspects of care.

10. The NCI, CDC, AHRQ, CMS, VA, private voluntary organizations such as the American Cancer Society, and private health insurers should increase their support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. New research initiatives focused on cancer patient follow-up are urgently needed to guide effective survivorship care.

This article is reviewed here:

Review of "The Evolving Paradigm of Adult Cancer Survivor Care"

Disclosures:

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

References

1. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor-Lost in Transition. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006, p. 2.

2. Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al: SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975â2004. National Cancer Institute, 2006. Available at:

http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/

. [Based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2007.] Accessed January 11, 2008.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. Available at:

http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf

. Accessed February 15, 2008.

4. People Living With Cancer. About Survivorship. Available at:

http://www.plwc.org/PLWC/Survivorship/About+Survivorship

. Accessed February 12, 2008.

5. Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM: Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(24): 5814â5830, 2005.

6. Ganz PA: Monitoring the physical health of cancer survivors: A survivorship-focused medical history. J Clin Oncol 24(32): 5105â5111, 2006.

7. NIH Research Radio. Podcast 2007 Show Notes, episode 0039, June 29, 2007. Available at:

http://www.nih.gov/news/radio/podcast/2007shownotes.htm#e0035

. Accessed February 12, 2008.

8. Hoffman B: Cancer survivors’ employment and insurance rights: A primer for oncologists. Oncology (Williston Park) 13(6): 841â846; discussion 846, 849, 852, 1999.

9. Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Alley LG, Pollack LA: Health insurance coverage and cost barriers to needed medical care among U.S. adult cancer survivors age

How Supportive Care Methods Can Improve Oncology Outcomes

Experts discussed supportive care and why it should be integrated into standard oncology care.