Female Representation in Clinical Practice Guideline Panels in 2 Major Cancer Organizations

Although female representation for National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines has increased to at least 50%, participation in guideline panels across all organizations is still less than 30%.

ABSTRACT

Background: While female representation in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) has been studied to a limited degree, the change in gender disparity over a decade, among all NCCN and ESMO CPG panelists has not been studied. Our study evaluated gender disparities for all NCCN and ESMO CPG panels (CPGPs) as of 2020 in comparison with 2010.

Methods: The 2010 and 2020 NCCN and ESMO CPGPs were examined, utilizing their websites and archives. We catalogued the number of females vs male panelists for each CPG by reviewing their names, Google search results, and panelists’ picture on affiliated websites. We defined greater than 50% representation of either sex in a CPG as “predominant” representation.

Results: Sixty NCCN/2020, 51 NCCN/2010, 78 ESMO/2020, and 55 ESMO/2010 CPGPs were reviewed. NCCN 2010 CPGPs had 27.1% female representation. CPGPs for solid tumors and hematological malignancies were male predominant. CPGPs for breast cancer screening, palliative care, and older adult oncology were female predominant. ESMO 2010 CPGPs had 23.2% female representation. Solid tumors (35 CPGPs) and hematological malignancies (9 CPGPs) were male predominant. CPGPs for cancers specific to women were female predominant.

NCCN 2020 CPGPs had 55.5% female representation. For solid tumors, 24 CPGPs had male predominance, and hematological malignancies, with 14 CPGPs, had female predominance. CPGPs for cancers specific to women had more female panelists. ESMO 2020 CPGPs had 27.8% female representation. CPGPs for solid tumors (37 panels) and hematological malignancies (17 panels) were male predominant. Breast and ovarian cancer CPGPs were female predominant.

Conclusions: Over the past decade, female representation in NCCN CPGs has doubled, with more than 50% representation among its 60 CPGPs in 2020. In ESMO, although there has been an increase in women participating in CPGPs for hematological malignancies, overall female representation remains low (<30%). Progression toward gender equity is important for improving outcomes in science and medicine.

Keywords: Female representation, oncology leadership, clinical practice guidelines, women in oncology

Oncology (Williston Park). 2022;36(1):59-63.

DOI: 10.46883/2022.25920942

Introduction

Female enrollment into medical schools in the United States1-3 and Europe4 has reached more than 50% of the total. Female representation in the field of hematology and oncology has steadily increased and doubled over the last 2 decades. Women constitute approximately 36% of total academic hematology/oncology faculty in the United States.5,6 According to the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges physician specialty report data,7 in 2019, 45% of all adult hematology oncology fellows were female. A total of 70.5% of pediatric hematology oncology fellows and 30.3% of radiation oncology residents were female. The number of female oncologists in Europe has been steadily growing as well; more than 40% of European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) members are female.8 That being said, recent studies show that gender disparity exists in academic oncology faculty positions5 and that there are substantial gendered differences in oncology publications.9 Academia and research compose the basic platforms for leadership roles in the development of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for any specialty.

CPGs are statements systematically developed to guide practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. These guidelines are developed by panel members who are both clinicians and researchers. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) in the United States and ESMO are 2 major cancer organizations engaged in the development of CPGs. Their guidelines are used worldwide by medical oncologists to deliver appropriate quality of care to their patients.10,11

While female representation in a limited set of NCCN and ESMO CPG panels (CPGPs) has been studied, changes in gender disparities over time among all NCCN and ESMO CPGPs has not been studied. Our study evaluated gender disparities for all NCCN and ESMO CPGPs as of 2020 in comparison with 2010.

Methods

The 2010 and 2020 versions of NCCN CPGPs were requested from NCCN for research use. ESMO CPGPs were examined utilizing their respective website and archives. We included all CPGPs inclusive of oncology, hematology, supportive care, prevention, and specific population guidelines. We catalogued the number of female vs male panelists for each CPGP. We discerned the sex of the panelists based on their first names and, when uncertain, we did additional Google searches and looked up each panelist’s name and picture on their affiliated institutional websites. We analyzed each guideline panel separately, and therefore the few individuals serving on multiple NCCN CPGPs were counted more than once.

Results

The numbers of female and males on CPGPs were reviewed for NCCN 2020 (60 CPGPs), NCCN 2010 (51 CPGPs), ESMO 2020 (78 CPGPs), and ESMO 2010 (55 CPGPs) inclusive of all cancers by site, detection prevention and risk reduction, supportive care, and guidelines for specific populations.

NCCN 2010 had 51 CPGPs (Table) with 1267 panelists; 72.9% were male and 27.1% were female. Of the 29 solid tumor CPGP members, 82% were male and 18% female. Of the 7 CPGPs related to hematological malignancies, 75% of panelists were male and 25% were female. There were 15 CPGPs related to supportive care, prevention, and specific populations; here, a total of 52.5% panelists were male and 47.5% were female. CPGPs specific to breast cancer screening, palliative care, and older adult oncology were female predominant. CPGPs associated with male cancers had predominantly male representation.

ESMO 2010 had 55 CPGPs (Table) with 228 panelists. CPGPs for solid tumors had 35 CPGs; 76.8% of panelists were male and 23.2% were female. In the 9 CPGPs for hematological malignancies, 95% of panelists were male and 5% were female. In the 11 CPGPs for supportive care, prevention, and specific populations, 71.9% of panelists were male and 28.1% were female. CPGPs for breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers were female predominant. CPGPs for thyroid cancer, endometrial cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and malignant pleural mesothelioma had equal numbers of female and male panelists. The CPGPs for cancers associated with males were predominantly male.

TABLE. Female and Male Panelists in ESMO and NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines

Of the total 2522 NCCN 2020 panelists in 60 CPGPs, 1400 (55.5%) were female and 1122 (44.5%) were male. A total of 35 (58%) NCCN CPGPs had predominant female representation and 24 CPGPs (40%) were male predominant. CPGPs for solid tumors had 24 CPGs with 50.8% male and 49.2% female panelists. Hematological malignancies had 14 CPGPs; panelists were 56.6% female and 43.4% male. The remaining 22 panels covered CPGs including supportive care, prevention, and specific populations; the panelists were 62.9% female and 37.1% male. CPGPs for cancers specific to women (breast, cervical/uterine and ovarian) had higher proportions of female panelists. CPGPs for central nervous system cancers had equal male and female panel representation. CPGPs for cancers associated with males (prostate cancer and detection, testicular cancer, penile cancer) had predominantly male representation.

ESMO 2020 had a total of 78 CPGPs (Table) with 802 panelists. Of these, 72.2% were male and 27.8% female. There were 37 CPGPs for solid tumors, with 72% male and 28% female panelists. Hematological malignancies had 17 CPGPs, with 85% male and 15% female panelists. Supportive care, prevention, and specific populations had 24 CPGPs, with 63.7% male and 36.3% female panelists. CPGPs for breast cancer and ovarian cancer were female predominant. CPGPs for thyroid cancer, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, dyspnea in advanced cancer patients, and chemotherapy extravasation had about equal numbers of female and male panelists. CPGPs for cancers associated with males (penile, prostate, and testicular cancers) were predominantly (>75%) male.

Discussion

In this study, we explored female representation in the CPGPs of 2 major cancer organizations over the last decade. Our study demonstrates that the gender gap in CPG panel membership has narrowed to a greater extent in the United States vs Europe. Whereas female representation on NCCN CPGPs nearly doubled from 2010 to 2020 (increasing from 27.1% to 55%), female representation on ESMO CPGPs rose from 23.2% to just 27.8% in the same time period.

CPGs are essential tools for clinical decision making, and their content ideally reflects diversity among both the patient population and the authors. The practice of oncology includes men and women of diverse races, ethnicities, and cultures working toward a common goal of optimal cancer care. Inclusion of women in international CPG development improves gender responsiveness of the health sector workforce, making panel member diversity key in producing CPGs that are relevant to patient-specific considerations.12

In that respect, the percentage of women represented in NCCN CPGPs has increased over time and there is now gender parity. “Gender equity on our panels is thus a reflection of the commitment and efforts of our member institutions to assure equitable opportunity and representation on our panels,” NCCN CEO Robert Carlson, MD, has said.13 However, the authors of a 2019 study expressed concern that women may still be underrepresented in NCCN guideline panels for certain cancers, relative to their scientific activity in those fields.5 Our study confirms that 35, or 58%, of the NCCN CPGPs had >50% female representation, indicating that the earlier trend of women being involved in CPG development for female-predominant cancers has now expanded to other types of cancer as well.

The observed trend may be due to a variety of reasons. The number of female physician-scientists in oncology has sharply increased in the past decade,9 coincident with the increase in representation on NCCN CPGPs observed in our study.

Dey et al, in their recently published study in Journal of National Comprehensive Cancer Network14 hypothesize that, “one possible explanation is that the proportion of women working in the fields of female-predominant cancers have achieved a critical ‘threshold,’ in which there are now a sufficient number of mid- and late-career female oncologists to provide strong mentorship, support.” Thus, there may be an impetus to encourage female trainees and junior faculty to consider specializing in other types of cancer as well.

Green et al, in their study in Lancet Oncology6 note that, “Nearly half of US hematology-oncology fellowship trainees are women, and the proportion of female academic oncology faculty, which is increasing at the same rate as that of trainees, approached 40% in 2019." They hypothesize that, “as more women enter the academic oncology community, we expect that the percentage of women in senior leadership positions will continue to increase. However, this outcome depends primarily on efforts to bolster the academic experience and outcomes for the current cohort of female junior faculty members to ensure their research potential is realized.”

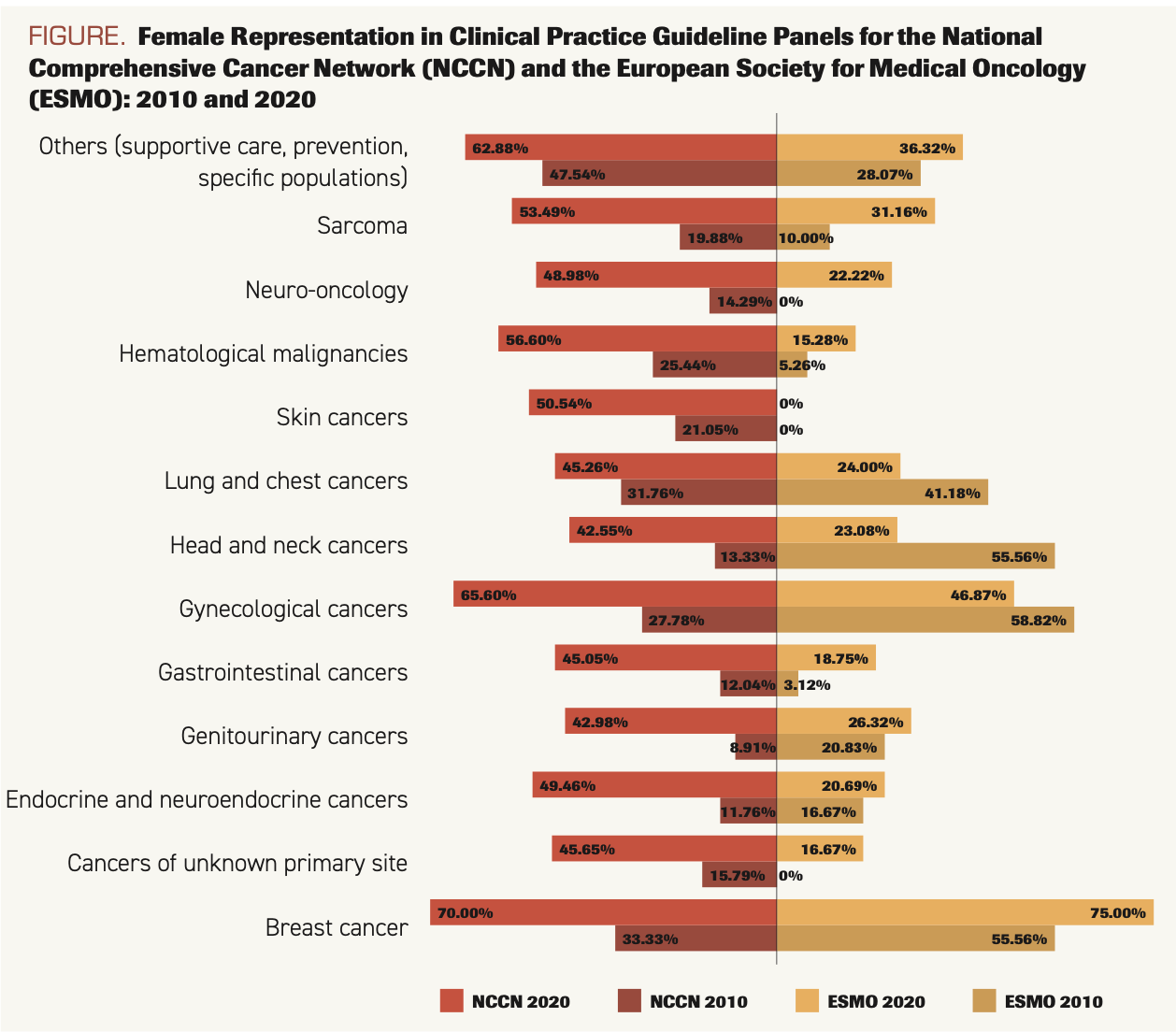

The relative underrepresentation of women in oncology practice, in general oncology leadership positions in particular, was recognized by Martine Piccart, MD, PhD, who, as ESMO president in 2013, began the Women for Oncology (W4O) initiative. It focuses on power sharing to foster gender equality in the oncology workforce. Through keynote presentations, testimonies from national networks, and small group discussions, the W4O initiative explores opportunities for creating a more diverse and inclusive culture that values differences and collaboration.5 Improvement has been noted; women continue to have majority representation in CPGPs for female-predominant cancers, and female representation has grown in CPGPs related to hematological malignancies (5% to 15%), neuro-oncology (0% to 22%), sarcomas (10% to 31%), and cancers of unknown primary site (0% to 17%) (Figure). Equal representation was noted in the Waldenström macroglobulinemia CPGP and 2 CPGPs related to supportive care.

FIGURE. Female Representation in Clinical Practice Guideline Panels for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO): 2010 and 2020

Nonetheless, a survey by the W4O conducted in 2016 to explore possible barriers to achieving gender parity in leadership revealed that, according to 52.8% of male and female respondents, the lack of opportunity for work-family balance was the major barrier. Perception-based barriers to leadership were also important: 39.9% of female respondents said that men are perceived as natural leaders while women are perceived more as team members and supporters, and 22.8% of female respondents noted that cultural gender prejudice exists due to misconceptions about family and domestic responsibilities of women.15

These findings were supported by replies to a survey of academic clinical department chairs who cited the constraints of traditional gender roles, manifestations of sexism in the medical environment, and lack of effective mentors as elements that affect the integration of women into leadership roles at universities. They also raised the possibility that women may devote more time to teaching and clinical activity.16

Many organizations and universities, and the government sector, have mandated gender equity, diversity representation, transparency, and public reporting of gender ratios.17,18 Educating about gender disparity is a critical part of the path forward, which includes integrating gender stereotype awareness and the value of diversity into plans to improve outcomes in science and medicine. It is important to monitor gender trends to raise awareness, advocate for policies, and establish new initiatives to overcome gender disparities. Mitigating this bias is important to encourage more females to enter the oncology workforce and to bring the community closer—all with the ultimate goal of improving cancer care.

Conclusions

Over the last decade, the proportion of female panelists in NCCN CPGPs has doubled, with more than 50% of members of 60 CPGPs in 2020 being women. In ESMO, although there was an increase in female representation in a few CPGPs from 2010 to 2020, overall female representation remains low (<30%). By continuing to examine these trends, we can create awareness and work toward developing appropriate targeted interventions to improve gender disparities in the major organizations that create CPGs for cancer care.

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS:

Madhuri Chengappa, MBBS1; Ronald S. Go, MD2; Ariela Marshall, MD3; and Thejaswi K. Poonacha, MD, MBA4

1. Department of Internal Medicine, Nazareth Hospital, Philadelphia, PA.

2. Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

3. Department of Hematology-Oncology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

4. Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN.

Authors’ contributions

MC: Conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, formal analysis

RSG: Supervision, review, editing, and validation

AM: Review, editing and validation

TKP: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing, review, and editing

Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, June 4, 2021

Conflict of Interest: RSG received travel reimbursement from the NCCN to chair the histiocytic neoplasm CPG panel. The other authors have no disclosures.

References

- Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2005-2006. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1147-1152. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1147

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). The State of Women in Academic Medicine: the Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2013-2014. AAMC; 2014:5. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3qCQtBb

- More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017. News release. Association of American Medical Colleges; December 17, 2017. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3p06HFb

- Male and female Doktors. Healthcare in Europe. Published February 11, 2013. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3pFoWA7

- Chowdhary M, Chowdhary A, Royce TJ, et al. Women’s representation in leadership positions in academic medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200708. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0708

- Green AK, Barrow B, Bach PB. Female representation among US National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline panel members. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):327-329. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30065-8

- Physician specialty data report. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/30IqLlW

- Hofstädter-Thalmann E, Dafni U, Allen T, et al. Report on the status of women occupying leadership roles in oncology. ESMO Open. 2018;3(6):e000423. doi:10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000423

- Dalal NH, Chino F, Williamson H, Beasley GM, Salama AKS, Palta M. Mind the gap: gendered publication trends in oncology. Cancer. 2020;126(12):2859-2865. doi:10.1002/cncr.32818

- NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3qfj5Am

- ESMO Guidelines. European Society for Medical Oncology. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3GYt8ke

- Langer A, Meleis A, Knaul FM, et al. Women and health: the key for sustainable development. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1165-1210. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60497-4

- Mulcahy N. Surprise: US tops Europe for women oncologists on panels. Medscape Medical News. March 23, 2021. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://bit.ly/3GYt8ke

- Dey P, Green AK, Haddadin M, Bach PB, Mitchell AP. Trends in Female Representation on NCCN Guideline Panels. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(8):1084-1086. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2020.7571

- Banerjee S, Dafni U, Allen T, et al. Gender-related challenges facing oncologists: the results of the ESMO Women for Oncology Committee survey. ESMO Open. 2018;3(6):e000422. doi:10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000422

- Yedidia MJ, Bickel J. Why aren’t there more women leaders in academic medicine? the views of clinical department chairs. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):453-465. doi:10.1097/00001888-200105000-00017

- Mehta S, Burns KEA, Machado FR, et al. Gender parity in critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):425-429. doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0076CP

- 30% Club. February 1, 2021. https://bit.ly/3yM0jVm