Sexual Function of the Gynecologic Cancer Survivor

Current advances in the field of medicine have aided in the early detection and treatment of cancer, leading to an increased rate of survivorship among cancer patients after an initial diagnosis.

Current advances in the field of medicine have aided in the early detection and treatment of cancer, leading to an increased rate of survivorship among cancer patients after an initial diagnosis. Approximately 66% of people diagnosed with cancer are expected to live at least 5 years after diagnosis.[1] The National Cancer Institute has estimated that, as of January 2006, an astonishing 3.8% of the US population, or 11.4 million people, are cancer survivors.[2] Additionally, 60% of these cancer survivors are 65 years of age or older, and approximately 14% of the 11.4 million estimated cancer survivors were diagnosed 20 or more years ago,[2] thus giving rise to a population at risk for post-therapy complications.

Importantly, gynecologic malignancies represent 9% of the most common cancer sites.[2] The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2010 alone, 83,750 women in the US will have been diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy, including cancer of the cervix, ovary, uterus, vagina, vulva, and fallopian tube.[3] Thus, a large population of gynecologic cancer survivors exists in the United States, all with varied and unique survivorship concerns and many coping with late effects of their treatment. A significant proportion of gynecologic cancer survivors experience sexual dysfunction at some point of the survivorship phase, including loss of sexual desire, dyspareunia, loss of sensation in the genital area, and decreased ability to achieve orgasm.[4] Indeed, 50% of survivors of breast, gynecologic, and many other cancers report sexual dysfunction as the most common long-term effect of cancer treatment.[5]

Despite the large number of women suffering from compromised sexual function as a long-term effect of cancer treatment, it is discussed in healthcare literature that many providers overlook addressing sexual function needs.[5] Sexual health and function are based on many factors, including cultural influences, sexual preferences/orientation, and previous sexual experiences. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom surveying 27 physicians and 16 nurses, Stead et al noted that only 20% of nurses and 25% of physicians discussed sexual function with their patients.[6] The investigators said the rationale for this low level of communication by healthcare providers included their lack of a sense of personal responsibility, lack of knowledge and experience, feelings of embarrassment, and a lack of resources to provide support, if needed.

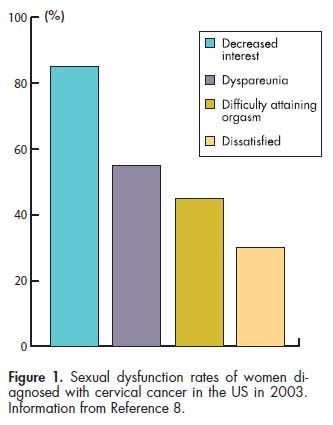

Most commonly, survivors of gynecologic malignancies report loss of desire and pain with sexual activity.[7] Jensen et al noted that of women who were disease-free after radiotherapy for locally advanced, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer, 85% reported little to no interest in sexual activity, 55% experienced dyspareunia, 45% had difficulty attaining orgasm and finishing sexual intercourse, and 30% experienced dissatisfaction with their sexual lives (see Figure 1).[8]

Surgical interventions are sometimes necessary to treat gynecologic malignancies, and include vulvectomy, pelvic exenteration, hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, surgery to remove cervical tumors, lymph node dissections, and local excisions, all of which have high potential to cause dyspareunia.[9] Many women treated for gynecologic malignancies describe dyspareunia as one of the two most common side effects of treatment.[5] Inducing premature ovarian failure or early menopause with pelvic radiation therapy, bilateral oophorectomy, and/or treatment with certain chemotherapeutic agents can cause vaginal dryness, leading to discomfort during sexual intercourse.[5] Shortened vaginal length may be a result of surgery, radiation therapy, or a combination of both. Jensen et al note that 6 months after treatment with radiation, women reported sexual dissatisfaction and discomfort related to the decrease in their vaginal size.[8]

Additionally, women may experience lack of desire or a decreased interest in sexual intimacy for a multitude of reasons. It is a very common side effect of treatment for gynecologic malignancies and is the second most common effect of gynecologic cancer treatment.[5,7] Sensory changes as a result of treatment may be attributed to lack of desire and inability to achieve orgasm.[5] During or immediately after cancer treatment, women can experience nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and a host of other physical complaints that may make sexual intimacy more challenging.[5] Postcoital vaginal bleeding is also of concern to many gynecologic cancer survivors. While this type of bleeding may simply be related to vaginal atrophy and dryness, disease recurrence may also elicit the same symptom, thus causing significant anxiety and fear. Evaluation by a healthcare provider may alleviate any worry.

In addition to the physical challenges faced by gynecologic cancer survivors, there are many psychosocial aspects to sexual dysfunction in the cancer survivor. She may experience depression, anxiety, body image concerns, fear, anger, and guilt. While sexual dysfunction may lead to depression, it is important to note that use of certain antidepressants for treatment is also known to contribute to sexual dysfunction.[10,11] Many women experience significant anxiety about the possibility of disease recurrence. Survivors also may have anxiety related to the prospect of resuming sexual activity following surgery, including uncertainty about how it will feel and as-yet-unanticipated sexual changes, as well as pressure to satisfy their sexual partner.[5,12]

Depending on the woman’s unique circumstances, she may be concerned about her physical appearance, as it may have been altered in some way by treatment. For example, she may have undergone a vulvectomy, which changes the physical appearance of the outer genitalia, or she may have required a colostomy due to bowel involvement. She may be anxious about her partner’s response to her new body, fearing that her partner will not respond well to her new appearance.

CASE STUDYInitial Presentation

The patient, “JD,” is a 67-year-old woman who initially presented to her gynecologist with postmenopausal spotting. Radiologic imaging revealed a thickened endometrium, a large pelvic mass extending from her uterus, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. An office endometrial biopsy revealed adenocarcinoma. JD’s gynecologic oncologist performed a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy, and lymph node dissection with small bowel resection, and JD was diagnosed with a stage 4a endometrial adenocarcinoma. She went on to receive eight cycles of intravenous Taxol (paclitaxel) and Paraplatin (carboplatin) followed by 50.4 Gy of pelvic radiation therapy. She subsequently received 1,200 Gy vaginal brachytherapy. During her course of chemotherapy she developed bilateral pulmonary embolism and was treated with Coumadin (warfarin).

Following radiation therapy, JD has experienced occasional hematuria related to radiation-induced cystitis confirmed on cystoscopy and has occasional loose bowel movements that are attributed to radiation-induced colitis, confirmed by colonoscopy. She now has a shorter vagina and mild to moderate vaginal scarring from the brachytherapy she received. This causes her some discomfort during follow-up pelvic examinations, use of vaginal dilators, and vaginal intercourse. Additionally she has severe vaginal dryness caused by significant vaginal atrophy. She uses the recommended vaginal dilator inconsistently because of discomfort, but on average she uses it once to twice weekly. Prior to her cancer diagnosis, JD and her husband enjoyed what she feels was a healthy level of sexual functioning. On average, they had vaginal intercourse 1–2 times weekly, without difficulty. She did not have problems with vaginal pain or lubrication.

Evaluation and Nursing Care

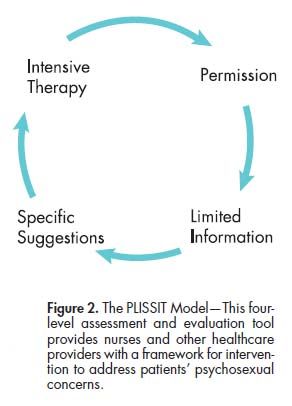

• Step 1: Permission- When JD returned to her healthcare provider for a follow-up visit, her provider used the PLISSIT model of sex therapy (see Figure 2), a four-level assessment and evaluation tool that allows healthcare providers to identify what role they play in the evaluation of a person’s sexual wellbeing.[13] The four levels of intervention are: Permission (P), Limited Information (LI), Specific Suggestions (SS), and Intensive Therapy (IT).[4,5,13]

JD’s provider initially discussed with her that any concerns regarding sexuality and sexual function are normal and opened the lines of communication with her. At that point, JD said that she had been experiencing pain on penile insertion and with deep penetration. She went on to report mild postcoital bleeding, which she said has been causing her significant anxiety, as she is afraid that her cancer may have returned. She and her husband have intercourse 1–2 times monthly due to her pain, frustration, and decreased libido; this is distressing to her.

• Step 2: Limited information-

JD’s provider reassured her that what she was feeling is normal and a result of her cancer treatment. She educated JD about why she was experiencing these effects and the impact that her cancer treatment may have had on her level of sexual functioning. During this time, JD underwent a physical examination, the results of which were normal overall. Her genitourinary exam revealed normal external female genitalia. On speculum exam, she was noted to have a shortened and atrophic vagina, without any visible signs of tumor recurrence. Her pelvic and rectovaginal exam were normal and did not reveal any masses or findings of concern. Her most recent CT scan, tumor markers, and Pap smear were all normal and were discussed with her. She felt reassured that her cancer was in clinical remission.

• Step 3: Specific suggestions- At that point, JD’s healthcare provider discussed with her some interventions that may be helpful in alleviating some of her symptoms. JD’s vaginal dryness is likely associated with estrogen insufficiency induced by bilateral oophorectomy. Given her history of endometrial cancer, use of estrogens is controversial, with several retrospective studies published on the issue. In 1986, Creasman et al suggested that women who were previously treated for endometrial cancer could be given hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to control vasomotor symptoms.[14]

There has been one match-controlled study of outcomes among 75 women with a prior history of endometrial cancer who were given HRT after completion of treatment, compared with a like number who did not receive HRT.[15] With an HRT duration of 83 months, the investigators noted that the endometrial cancer recurrence rate was 1% among women who received HRT vs 15% among those who did not (P = .006).[15] Despite the benefit to HRT suggested by these results, use of HRT in women with a history of endometrial cancer is a highly individualized decision and should be made with caution.

Because of JD’s personal history of bilateral pulmonary emboli, her oncologist did not recommend that she receive vaginal estrogen to treat her vaginal dryness, so it was recommended that she use over-the-counter non-hormonal water-soluble vaginal lubrication with intercourse and dilator use. She was also encouraged to increase her precoital foreplay.

In terms of her anxiety, JD told her provider that she did not want to use any medications to treat it and would prefer an alternative treatment. To address her anxiety, she was encouraged to try meditation and guided imagery.

• Step 4: Intensive therapy-To better assist her, JD’s healthcare provider referred her to a local sex/relationship therapist for additional counseling and recommendations. JD was eager to begin therapy.

OUTCOME

At her 3-month follow-up appointment, JD reported that her symptoms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and anxiety had significantly improved. She and her husband increased their precoital foreplay and used water-soluble vaginal lubricants, which aided in vaginal lubrication. Despite a few setbacks, she reports that the vaginal dryness, pain, and postcoital spotting are continually improving. She and her husband also sought the assistance of a sex/relationship therapist. The couple were able to communicate their fears and concerns, which JD feels brought them closer together. JD was able to decrease her anxiety through discussion and meditation, and has stated that she feels satisfied with her marriage and sexual functioning at this point.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that sexual dysfunction is prevalent among gynecologic cancer survivors. As demonstrated in the case study, post-treatment sexual dysfunction can be distressing and challenging to overcome. It is important that healthcare providers address sexual dysfunction. The PLISSIT model is a useful tool to encourage patients to discuss their concerns in order to initiate rehabilitation.

Utilizing the PLISSIT model empowered JD to openly discuss her concerns about her post-treatment sexual function, which enabled her provider to offer her with appropriate recommendations and referrals to address her concerns. With this in mind, healthcare providers may need additional training in communication about sexual dysfunction and information about treatment modalities to care for their patients holistically.

References:

References

1. Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, et al (eds): SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975â2007. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER Web site, 2010.

2. Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al (eds): SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975â2006. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/, based on November 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2009.

3. American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/acspc-024113.pdf. Accessed on September 6, 2010.

4. Bodurka DC, Sun CC: Sexual function after gynecologic cancer. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 33(4):621â630, 2006.

5. Stilos K, Doyle C, Daines P: Addressing the sexual health needs of patients with gynecologic cancers. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12(3)457â463, 2007.

6. Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, et al: Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer 88(5):666â671, 2003.

7. Booth S, Bruera E: Palliative care consultation in gynaecology, in Tate T (ed): Psychosexual Problems in Gynecological Malignancy. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004.

8. Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, et al: Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol 56(4):937â949, 2003.

9. Jenkins M, Ashley J: Sex and the oncology patient: Discussing sexual dysfunction helps the patient optimize quality of life. Am J Nurs 102(1):1â15, 2002.

10. Schover LR: Sexuality and Fertility After Cancer. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1997.

11. Schover LR, Montague DK, Lakin MM: Sexual problems, in Devita Jr. VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA (eds): Cancer: Principles and Practices of Oncology, 5th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1997, pp 2857â2872.

12. Zegwaard MI, Gamel CJ, Dugris DJ, et al: The experience of sexuality and information received in women with cervical cancer and their partners. Verpleegkunde 15(1):18â27, 2000. [Dutch]

13. Taylor B, Davis S: The extended PLISSIT model for addressing the sexual wellbeing of individuals with an acquired disability or chronic illness. Sex Disabil 25(3):135â139, 2007.

14. Creasman WT, Henderson D, Hinshaw W, et al: Estrogen replacement therapy in the patients treated for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 67(3):326â330, 1986.

15. Suriano KA, McHale M, McLaren CE, et al: Estrogen replacement therapy in endometrial cancer patients: A matched control study. Obstet Gynecol 97(4):555â560, 2001.