The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Palliative Oncology: Zeroing in on Hematologic Malignancies

AI revolutionizes palliative oncology by enhancing prognostication, symptom management, and personalized care for patients with hematologic malignancies.

The authors

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is gaining attention for its potential applications in medicine, offering benefits to physicians and patients across various aspects of care. Integrating AI into health care aims to help clinicians personalize care and improve patient health by addressing challenges such as rising costs and lack of resources.1 The goal is to help improve health care efficiencies while reducing the need for human intervention. AI is already being utilized in areas such as supporting treatment plans, diagnosing diseases, predicting patient outcomes, enhancing operational efficiency, and improving patient monitoring.2 Despite growing interest, the medical community remains cautious about using AI-related tools in practice, potentially due to unfamiliarity or concerns about accuracy and ethical use.

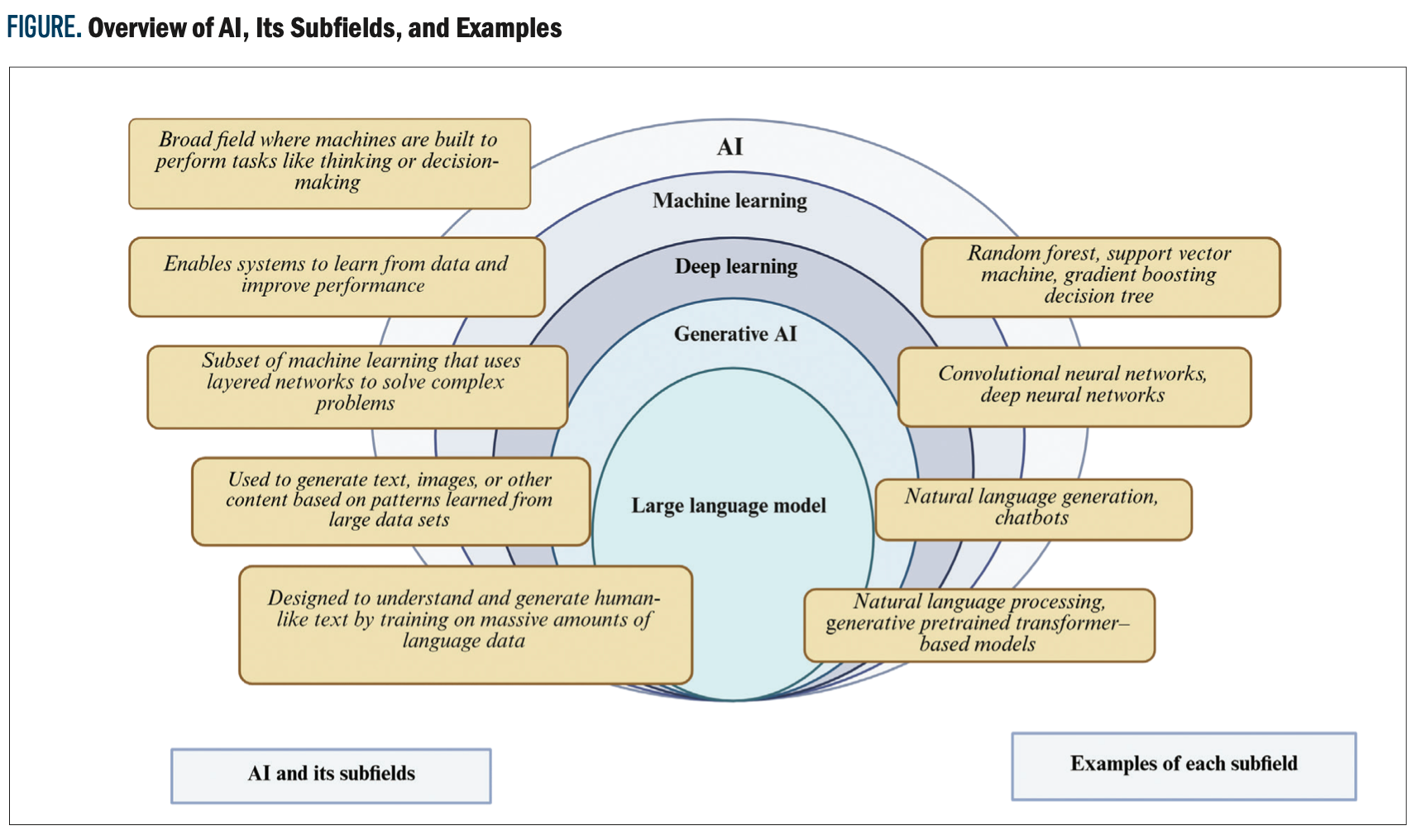

As AI becomes integrated into health care, it is vital that clinicians understand what it is and how it works. At its core, AI refers to computer systems designed to learn from data to help recognize patterns, make decisions, and support decision-making.1 Within AI, commonly used models include machine learning (ML), which can learn from structured data such as laboratory results and vital signs, and deep learning (DL), which can analyze complex data such as medical imaging and clinical notes. Techniques such as natural language processing (NLP) help AI interpret written language, and neural networks are used for image recognition and disease prediction models. The Figure shows a simple breakdown of the different types of AI and examples of commonly used models.

In studies by Esteva et al3 and Hekler et al,4 the authors used imaging data to develop models capable of aiding physicians in diagnosing various skin cancers and skin lesions. Esteva et al developed a deep convolutional neural network model using 129,450 images, and results showed that their model achieved a performance rate on par with 21 board-certified dermatologists while taking a fraction of the time of physicians who had trained for several years.3 A study by Knackstedt et al5 assessed 255 patients using a vision vendor-independent software to apply a machine learning algorithm to measure ejection fraction and longitudinal strain from biplane views of the left ventricle. It showed a predictive accuracy of 92.1%, with an average analysis time of 8 ± 1 sec/patient. Narula et al6 looked at the diagnostic ability of a machine learning framework that studies echocardiographic data to distinguish hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) from physiological hypertrophy in athletes. When looking at data from 77 athletes and 62 patients with HCM, AI had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 82%, respectively, for diagnosing between HCM and physiologic hypertrophy.

In 2020, AlphaFold, a DL AI system, was established to help predict the 3D structures of proteins, which potentially could help in drug discovery and research.7 During the COVID-19 pandemic, AI systems employing natural-language processing (NLP) and ML were used to analyze large volumes of textual and unstructured data such as news articles, social media posts, and public health reports to support outbreak detection, trend forecasting, and situational awareness.8 This has led to the development of digital contact tracing platforms as an essential component of the global response against COVID-19.9

Despite AI’s growing presence in medicine, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding its role in helping clinicians and patients with holistic aspects of care.10 Potential concerns of using AI include reliability, accuracy, lack of prospective study,11 concerns about patient autonomy,12 and the need for training to integrate AI into practice.13 In palliative care, where the emphasis is on quality of life rather than curing the disease,14 AI has the potential to make a meaningful impact by assisting with symptom management, treatment planning, and understanding individual patient needs. This is particularly crucial for patients with blood cancers such as leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, who often present with complex symptoms and unpredictable disease trajectories.15,16 Unfortunately, there is limited research focused specifically on how AI can contribute to palliative care in this unique patient population.

This article offers a practical introduction to the use of AI in palliative oncology, with a special focus on hematologic malignancies. In this review, we use the term palliative oncology to refer to the integration of palliative care services, such as symptom management, communication, and psychosocial support within oncology care across the disease continuum. By focusing on AI’s current strengths and areas of future promise, as well as the gaps that will continue to require human insight and clinical judgment,we hope to give clinicians a clearer understanding of how these tools can be used in real-world settings. In doing so, this review article seeks to bridge the existing gap in literature by exploring the potential of AI to enhance palliative care for patients with blood cancers, shedding light on the progress made and the challenges and opportunities for future advancements.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of PubMed to identify studies on AI in palliative care and hematologic malignancies. For the palliative care section, articles published in 2023 and 2024 were reviewed, with a focus on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), resulting in 5 relevant RCTs. This narrower time frame was selected because many of the most directly relevant RCTs exploring AI in palliative care have been published recently. We aimed to highlight emerging applications in this evolving field and keep the review concise and focused. For the hematologic malignancies section, all available RCTs from 2000 to 2024 were searched, and only the most relevant studies were included, based on their applicability to AI in leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

The Role of AI in Palliative Care

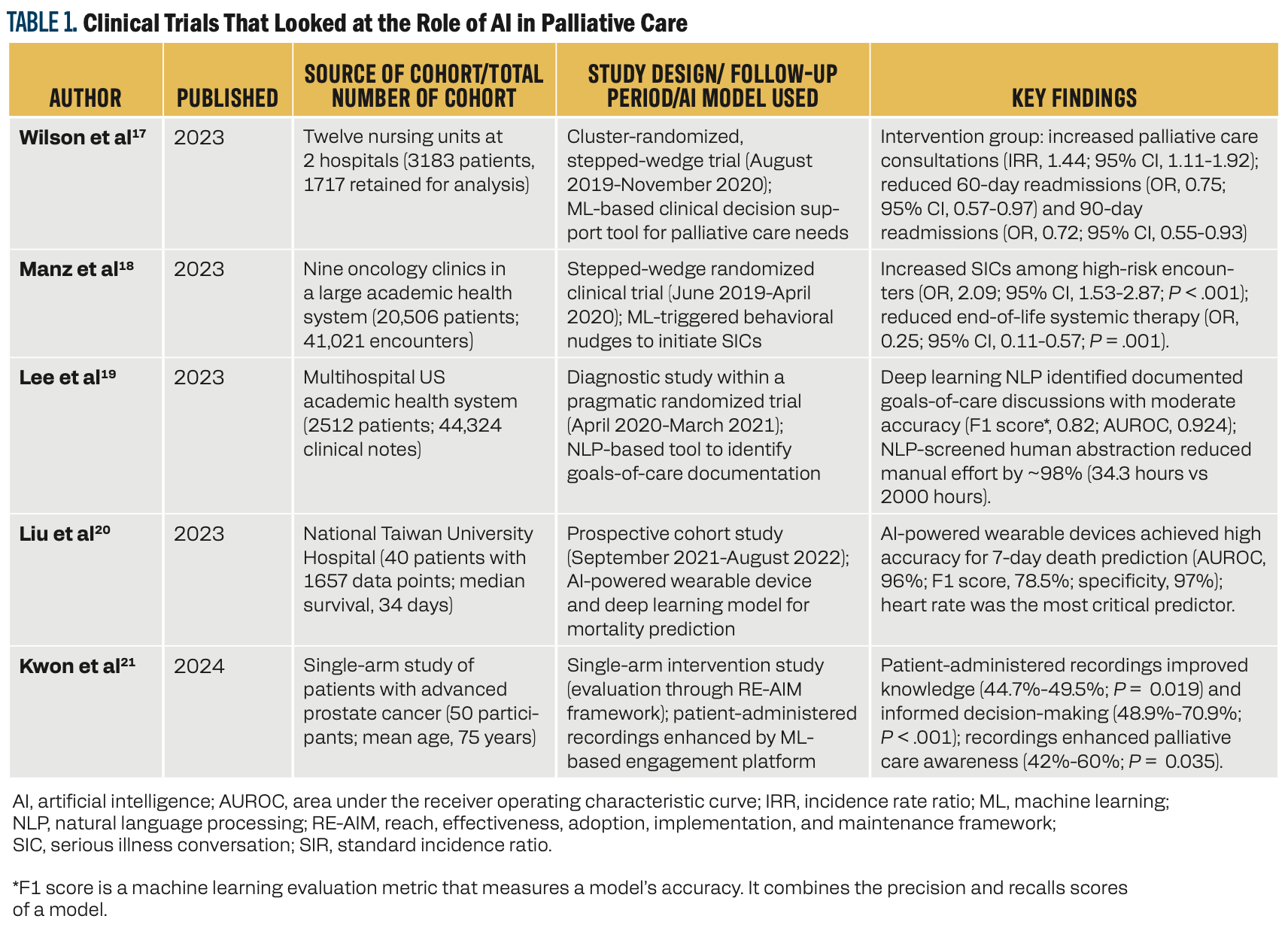

Table 1 highlights the clinical trials between 2023 and 2024 that examined the integration of AI into palliative care across diverse patient settings. These studies demonstrated the potential of AI-based interventions in enhancing outcomes for patients with serious or terminal illness. Wilson et al showed how AI-based decision support tools increased palliative care consultations and reduced hospital readmissions, whereas Manz et al demonstrated that ML-triggered behavioral nudges improved serious illness conversations and reduced the use of systemic therapy toward end of life.17,18 Lee et al showed the ability of NLP in documenting goals of care discussions with accuracy, thereby reducing manual effort required for abstraction.19 Liu et al explored the use of AI and wearable devices to predict 7-day mortality in patients with cancer who were terminally ill, achieving a good predictive accuracy and highlighting the importance of continuous physiological monitoring.20 Lastly, Kwon et al showed the utility of patient-administered mobile recordings in enhancing informed decision-making and awareness of palliative care.21 Collectively, these studies emphasized the critical importance of AI in enhancing patient care, improving clinical efficiency, and facilitating meaningful patient-clinician interactions.

AI for Enhancing Symptom Management

Chronic pain has a significant impact on patients and the health care system, with an estimated cost of $560 billion to $635 billion per year in the US.22 AI can help patients’ pain management by its ability to analyze large data sets and look for patterns in the patient population.23,24 This is particularly enhanced in patients with cancer who rely on palliative care physicians for their symptom management. A meta-analysis by Snijders et al analyzed 444 studies from 2014 to 2021, finding an overall cancer pain prevalence of 44.5%, with 30.6% of patients experiencing moderate to severe pain.25 Chronic pain persists due to ineffective therapies targeting symptoms over mechanisms, intrinsic patient differences, and variability in symptoms and treatment responses.24,26,27

AI has shown potential in addressing these challenges by improving cancer pain classification, risk prediction, and management strategies. A systematic review of 44 studies from 2006 to 2023 found that random forest models were among the most frequently used, and they performed well in predicting pain intensity, opioid responsiveness, and risk of chronic pain. In some studies, they outperformed traditional regression models in terms of accuracy and sensitivity, making them a promising tool for identifying high-risk patients and guiding treatment plans.28 AI can also help address challenges of self-reported pain, which tend to be inconsistent and subjective. Automated pain assessment using AI provides standardized methods using facial expressions, language, and posture alongside neurophysiological signals using an electroencephalogram or electromyography to assess pain more accurately. Advanced AI models, such as neural networks, combine these methods for better results.29,30 AI can thus help in personalizing pain management by analyzing large data sets to identify unique pain profiles. This involves collecting detailed patient information (ie, medical history, symptoms, and lifestyle factors) using AI algorithms such as K-means clustering, Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise, and gaussian mixture models to group patients into subtypes based on shared pain characteristics. These subgroups can guide tailored treatments, which are tested through clinical trials to refine strategies and develop predictive AI models, such as logistic regression and random forest, to forecast individual responses

to therapy.

AI also has significant potential for managing other challenging symptoms commonly faced by patients in palliative care, such as fatigue, depression, anxiety, and nausea/gastrointestinal distress. Masukawa et al31 analyzed 1,554,736 clinical records of 808 patients with cancer who were terminally ill (within 1 month of death). They developed ML models to detect social and spiritual distress and other symptoms. The models achieved high accuracy with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) values, with 0.98 for social distress, 0.90 for spiritual distress, and greater than 0.80 for symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.31 Similarly, AI tools such as NLP can analyze data from electronic health records (EHRs), text, and speech patterns to detect emotional distress. ML algorithms such as support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression, and neural networks help detect mental health disorders and predict disease onset and treatment responses.32,33 A future direction could involve integrating these tools into real-time EHR systems to identify at-risk patients and assist with timely psychosocial interventions.

Smartphones and wearable devices can monitor patient vital signs and correlate them to outcomes. Investigators in a prospective observational study at Taipei Medical University Hospital in Taiwan continuously monitored hand movements of 68 patients in hospice or palliative care wards using wearable devices between December 2019 and June 2022. This approach provided real-time data to evaluate patient outcomes. Study of symptom patterns found that higher performance scores (Karnofsky Performance Status and Palliative Performance Scale) and movement data from wearables were linked to better survival chances, especially in the first 48 hours.34 Although these devices do not directly alleviate pain, their ability to support early prognostication may aid timely care planning, goal-setting discussions, and more tailored symptom management, potentially enhancing patient quality of life.

AI as Decision-Making Support

AI-driven predictive models can play a crucial role in enhancing decision-making in palliative care. For instance, a study by Huang et al utilized gene expression data from 175 patients to train an SVM model for predicting responses to standard-of-care chemotherapies. The model demonstrated an impressive prediction accuracy of over 80% across multiple drugs, highlighting AI’s promising role in guiding treatment decisions.35 Predictive models may also support oncologists in initiating prognosis discussions and help palliative care teams align care with patient values during follow-up conversations.

AI also shows potential in therapeutic drug monitoring and optimizing drug dosing for individual patients. By using ML algorithms to predict drug responses based on genetic and clinical data, AI helps physicians develop personalized therapy while reducing the risk of adverse drug reactions.36,37 This can further aid palliative care physicians in tailoring care for patients. Algorithm-aided prediction of patient preferences offers a promising solution for decision-making when patients are unable to express their wishes.38,39 However, algorithm-driven predictions of preferences rely heavily on prior clinical documentation, which may be incomplete, inconsistently recorded, or reflect subjective interpretations, introducing potential bias into decision-making. By using AI, including ML models, demographic and personal data can be analyzed to generate personalized predictions of care preferences, potentially surpassing the accuracy of surrogates or next of kin.40 These tools could reduce the emotional burden on families and align care with patient values.

Furthermore, AI allows health care providers to deliver care to patients in remote or resource-limited regions, overcoming barriers such as geographic distance and workforce shortages.41 AI-powered tools can prioritize care needs, monitor symptoms in real time, and provide virtual consultations by linking patients with remote providers, ensuring timely and equitable delivery of high-quality palliative care.42 These advancements underscore the transformative potential of AI in palliative care, enabling more personalized, efficient, and accessible treatment options for patients in need.

The Role of AI in Hematologic Malignancies

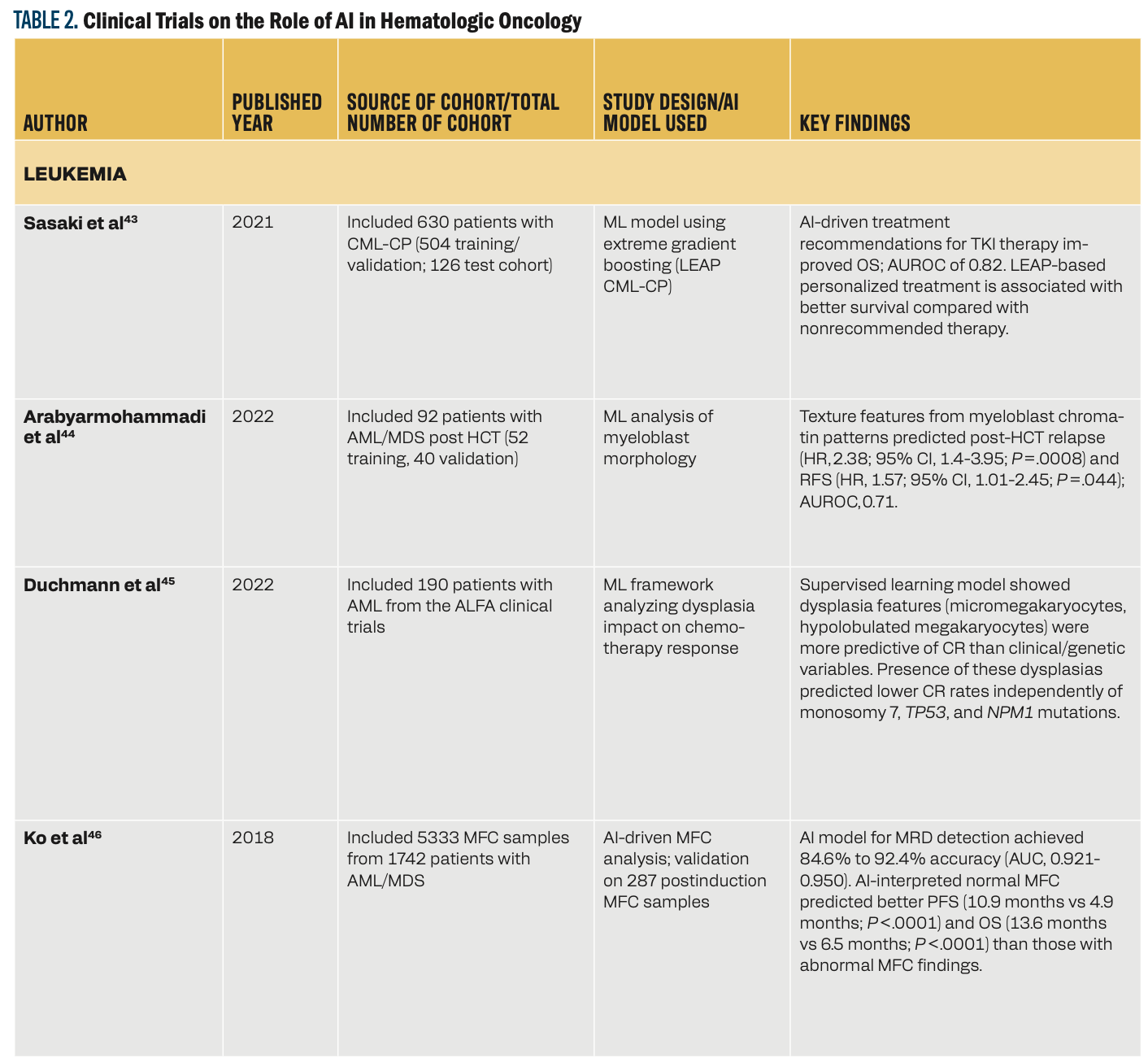

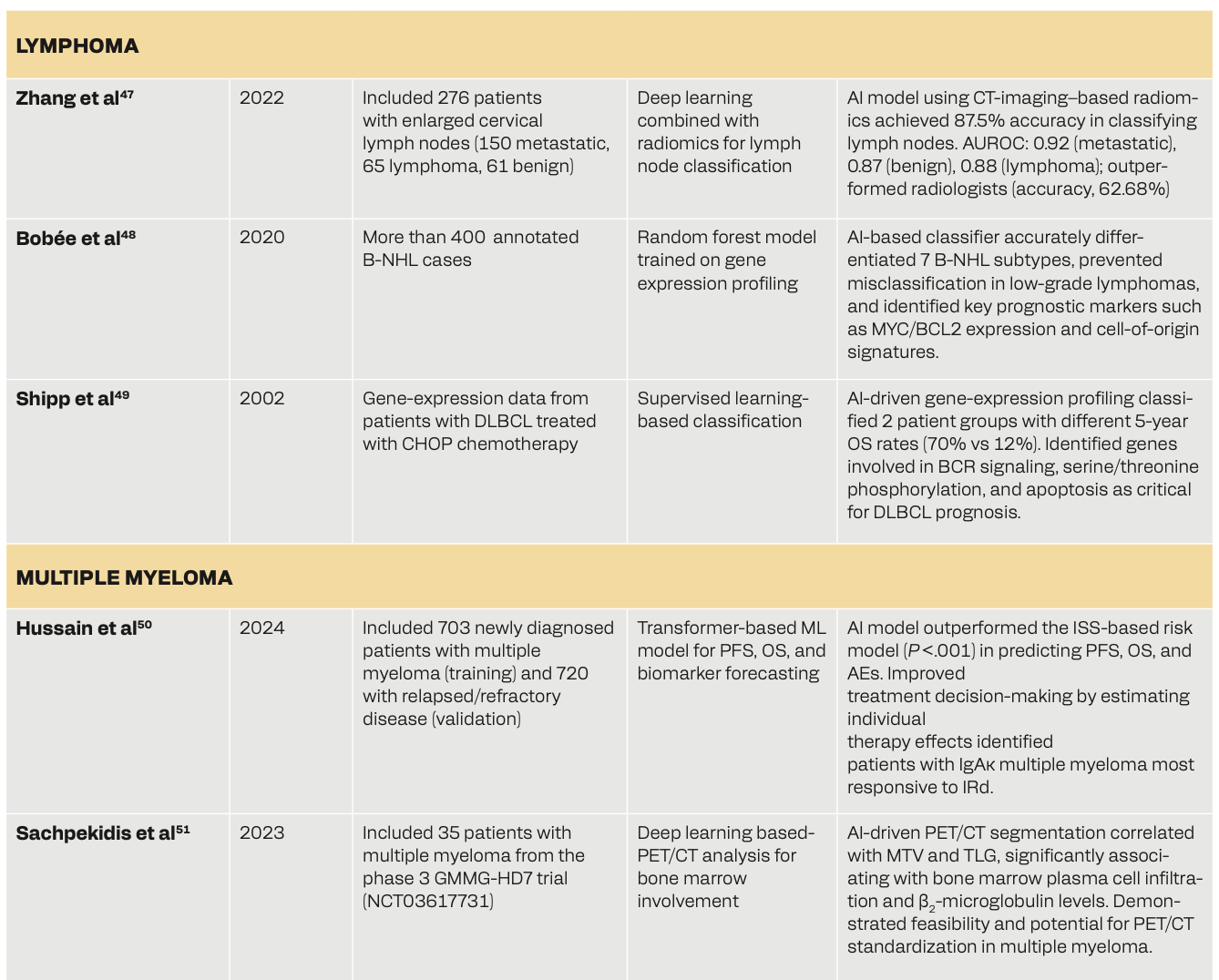

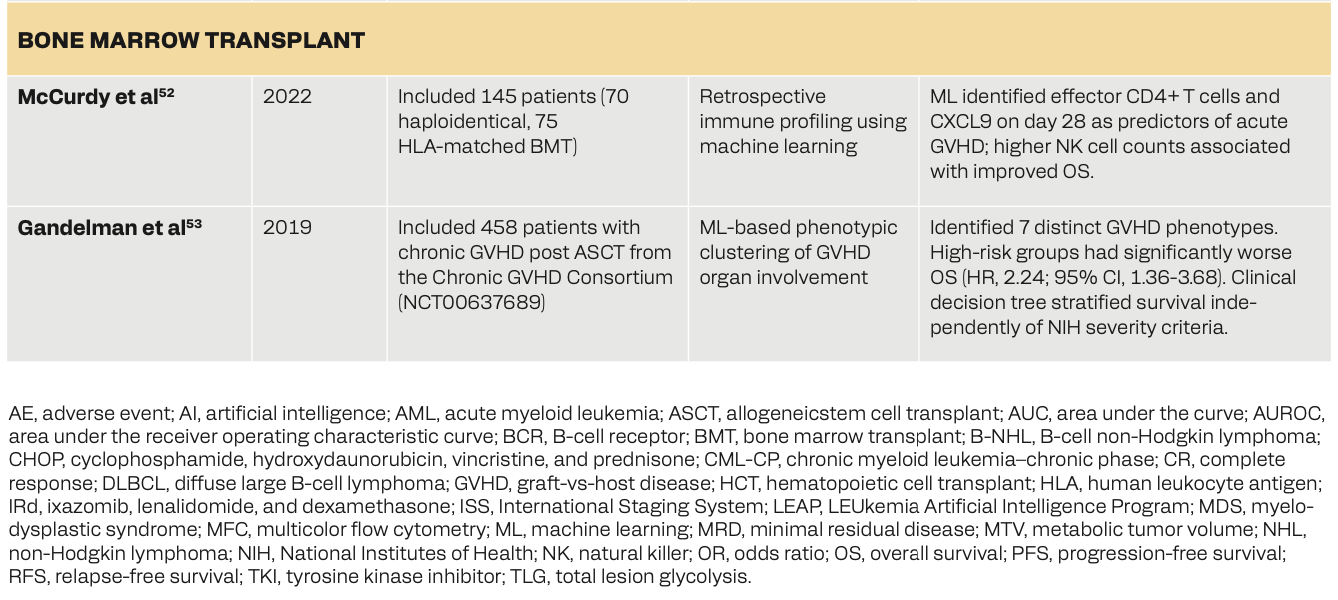

Table 2 shows how the use of AI in hematologic oncology can facilitate advancements in disease classification, prognosis prediction, treatment optimization, and response assessment. In leukemia, AI-driven models such as the LEUkemia Artificial Intelligence Program (LEAP) in chronic myeloid leukemia–chronic phase (CML-CP) have helped personalize treatments with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, improving survival outcomes.43 ML models have enhanced relapse prediction, minimal residual disease detection, and assessment of treatment response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/myelodysplastic syndrome.44-46 In lymphoma, DL and random forest models have helped in accurate disease classification, genetic profiling, and risk stratification, outperforming existing diagnostic approaches.47-49 Myeloma-based research has shown that machine and deep learning models have superior predictive capabilities for survival outcomes, adverse events, and biomarker changes, with PET/CT-based DL models used for bone marrow assessment.50,51 Lastly, AI has helped predict complications after bone marrow transplants52 and stratified graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) phenotypes.53 These studies collectively portray AI’s role in hematological malignancies for potentially improving diagnostic precision, personalized treatments, and survival prediction.

AI in Diagnostics

The diagnosis of hematologic malignancy can be challenging, given the complexities in differentiating subtle findings on pathology and subclassifying into respective categories within acute/chronic leukemia, lymphoma, or plasma cell dyscrasias.54 AI has demonstrated significant potential in improving hematologic cancer diagnoses. An ML model for AML detection and classification trained on peripheral blood smear images showed 92.99% accuracy for detection and 93.45% for classification of immature karyocytes using the image segmentation and a random forest classifier.55 Several other studies have investigated the use of AI-based models to detect leukemia.56-59 Similarly, for the detection of lymphoma, a DL–based AI classifier was developed to assist in malignant lymphoma diagnosis using whole slide images stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The model achieved 94.0% accuracy at 5-times magnification, 93.0% at 20 times, and 92.0% at 40 times, outperforming pathologists, whose average accuracy was 76.0% overall.60 Other studies have also looked at AI aiding the diagnosis of lymphoma.61-63

In multiple myeloma, an AI-based diagnostic system using routine blood and biochemical test data achieved early and accurate detection, with gradient boosting decision tree outperforming other models, achieving 92.9% precision, 90.0% recall, and an AUROC of 0.975, highlighting AI’s potential in enhancing early multiple myeloma diagnosis and management.64 AI-driven PET/CT imaging analysis has been used to assess bone marrow involvement, improving the detection of metabolic tumor volume and disease burden, which can aid in treatment planning and prognosis prediction. Recent studies have shown that AI-based tools can provide quantitative measures of marrow infiltration, with models demonstrating a strong correlation between PET/CT-derived metrics such as metabolic tumor volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) and actual plasma cell burden, allowing differentiation among varying degrees of involvement. For example, AI tools were able to stratify patients based on the extent of marrow involvement, with Sachpekidis et al51 reporting a significant association between MTV/TLG values and biopsy-confirmed infiltration, and Takahashi et al65 proposing standardized thresholds that helped differentiate between mild (< 30%) and extensive (> 60%) marrow infiltration. These advancements highlight AI’s growing role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and supporting clinical decision-making in hematology.

AI for Symptom Management

Patients with hematologic malignancies often have severe symptoms, including pain, fatigue, anemia, infections, and treatment-related toxicities, that affect their quality of life and treatment outcomes.66 They also experience cytopenias, infections, and coagulopathies, which require frequent hospitalizations, invasive procedures, continuous monitoring, and intensive therapies.67 Traditional symptom management relies heavily on clinical assessments and patient-reported outcomes. AI-driven models use EHRs, wearable devices, and real-time monitoring for early detection of symptoms and personalized supportive care.68 Wearable sensors integrated with AI and ML algorithms can track physiological changes, enabling proactive symptom management and tailored interventions.68,69 AI algorithms have shown promise in predicting hemoglobin trends and optimizing transfusion timings, thereby reducing unnecessary procedures and improving patient stability. For instance, DL models using smartphone-captured images of the inner eyelid (palpebral conjunctiva) have been developed to estimate hemoglobin levels noninvasively, using features such as color intensity and vascular patterns to assess anemia with high accuracy.70 Additionally, ML models trained on intensive care unit data—including vital signs, laboratory values, and clinical parameters—have been used to predict the likelihood of transfusion, facilitating timely decisions and potentially avoiding unnecessary blood product use.71,72 Similarly, AI-based pain assessment tools incorporating biomarkers and patient-reported data have shown potential in guiding medication administration and improving pain control strategies.29,73,74 ML models have also been used to predict febrile neutropenia, sepsis, and respiratory distress, enabling early interventions and reducing hospitalization risks in patients who are immunocompromised.75-78

Beyond its use in managing physical symptoms, AI is also being explored in supporting the psychological and emotional well-being of patients. NLP models analyzing clinician notes and patient-reported symptoms have been used to detect signs of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, which could potentially enable timely psychological support.79-81 AI-powered chatbots and virtual assistants are being designed to offer personalized symptom management, medication reminders, and self-care recommendations, adapting to real-time patient feedback for improved support.82,83 Although these studies highlight AI’s significant potential in symptom management, further prospective and retrospective research is essential to refine AI applications and tailor them to hematologic malignancies. Ongoing advancements in AI can transform symptom management, making it more precise, proactive, and personalized to individual patient needs.

AI can also assist clinicians in providing personalized care for patients with hematologic malignancies by tailoring treatments, symptom management, and supportive care interventions.43,84 AI-driven analytics may differentiate patients based on symptom burden, treatment response, and expected prognosis, allowing clinicians to make informed decisions regarding palliative interventions, timing of transfusions, and chemotherapy regimen adjustments.85-88 Wearable devices equipped with AI-powered monitoring tools can track vital signs, mobility, and treatment adverse effects, enabling proactive symptom management.89 These tools represent a shift toward a more patient-centered approach, ensuring that patients with hematologic cancers receive optimal, timely, and individualized support throughout their disease trajectory.

AI implementation in oncology is beginning to demonstrate tangible benefits, particularly in areas such as symptom monitoring and transfusion management. For instance, AI-driven decision support systems have been applied in hematology settings to help refine transfusion practices, reducing unnecessary interventions while ensuring patient safety.90 To support successful adoption, practical strategies include integrating AI tools with existing EHRs, ensuring clinician training, and promoting collaboration across oncology, palliative care, and informatics teams.91 Such efforts can help translate AI’s promise into sustainable, real-world solutions.

AI for Prognostication and Risk Stratification

Accurate prognostication and risk stratification are essential in hematologic malignancies, helping to guide treatment decisions, assess transplant eligibility, and monitor disease progression. Traditional prognostic models, such as the Revised International Staging System for multiple myeloma,92 the European LeukemiaNet classification for AML,93 and various risk stratification frameworks for lymphoma,94,95 rely on clinical and genetic markers but often lack personalized predictive capabilities. AI-driven models have demonstrated the ability to integrate multidimensional data, including genomic profiles, imaging, and EHRs, to improve survival predictions and risk assessments.96 In AML, ML algorithms incorporating cytogenetic and molecular markers have shown superior accuracy in predicting early mortality, relapse risk, and response to induction chemotherapy compared with traditional statistical models based solely on clinical and genetic variables, thus refining treatment decisions.97,98 In lymphomas, DL algorithms analyzing histopathology slides, radiomics, and gene expression data can classify patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and predict treatment outcomes.99,100

Beyond initial diagnosis, AI may be instrumental in risk stratification for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and posttreatment outcomes. Predictive models can assess GVHD severity, transplant-related mortality, and relapse risk by analyzing human leukocyte antigen compatibility, inflammatory biomarkers, and treatment protocols, leading to improved patient selection and personalized transplant strategies.101-103 As AI advances, its use in hematologic malignancies may be expected to enhance risk assessment, guide treatment decisions, and improve patient care with more personalized and data-driven approaches.

Beyond initial prognostication, AI has the potential to transform survivorship and end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies. Survivors often experience late treatment-related complications such as cardiotoxicity, immune dysfunction, and secondary malignancies.104 Predictive AI models analyzing EHR data, imaging, and biomarkers can track these late effects and facilitate early intervention.105,106 Personalized posttreatment monitoring tools can guide follow-up care schedules and anticipate complications.107,108

In end-of-life settings, AI prognostic models can help clinicians identify patients likely to benefit from early palliative care discussions or hospice referrals. For example, He et al developed an ML model predicting 1-year mortality in advanced cancer, enabling the integration of early palliative services.109 Similarly, Blanes-Selva et al used ML to forecast 1-year mortality at admission, promoting timely, proactive interventions.110 AI-powered chatbots and virtual health assistants can support symptom tracking, emotional well-being, and care coordination during survivorship and terminal care.111 These tools hold promise in improving quality of life and end-of-life experiences for patients with hematologic malignancies.

Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Although AI has great potential in palliative oncology and hematologic malignancies, several challenges must be addressed. From the patient perspective, concerns include data privacy, bias, consent, and potential loss of autonomy.112,113

From the physician’s perspective, AI may support decision-making, but it cannot replace the nuance, empathy, and individualized context required in palliative care. Clinicians must understand the limitations of these tools and apply them judiciously rather than defer blindly to algorithmic outputs. Additionally, although AI may help flag unmet palliative needs, its input should not replace clinical collaboration between oncology and palliative care teams. Instead, it should be a supportive tool to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue and shared decision-making.

At the health system level, challenges include ensuring equitable data representation, avoiding bias, and establishing accountability.112,113 Models are only as good as the data they are trained on, and poor-quality or nonrepresentative data can perpetuate disparities. In one real-world case, an algorithm used to predict health care needs in US hospital systems underestimated the needs of patients who were Black compared with patients who were White with similar comorbidities because it relied on health care spending as a proxy for health status, a measure influenced by longstanding differences in access and utilization.114 Similarly, overreliance on algorithmic predictions, such as prognostic estimates, without appropriate human oversight could lead to decisions that unintentionally limit care options.

To mitigate such pitfalls, several emerging frameworks emphasize the importance of algorithmic transparency, explainability, and continuous validation across diverse patient populations.115 Ethical implementation also requires clinicians to remain actively engaged in care decisions, ensuring that AI tools complement rather than replace shared decision-making between patients and providers.91 However, many AI tools, particularly those used in hematologic malignancies, still lack prospective validation, making their real-world effectiveness uncertain. Challenges such as clinician resistance, insufficient training, and limited infrastructure further complicate adoption. Thus, to integrate AI ethically and effectively, it is essential to strengthen data quality, provide clear regulatory guidance, and maintain human oversight throughout the clinical decision-making process.

Conclusion

AI can transform palliative oncology and the treatment of patients with hematologic malignancies by improving diagnostics, symptom management, and personalized care. By integrating predictive analytics, wearable monitoring, and AI-driven decision support, clinicians can enhance treatment planning, patient monitoring, and palliative care delivery. Additionally, AI tools in cancer survivorship and end-of-life care can facilitate earlier palliative care discussions, improve follow-up strategies, and optimize supportive care interventions. Future research should focus on prospective studies and interdisciplinary collaborations to refine AI’s role in patient-centered cancer care for hematologic malignancies.

References

1.Bekbolatova M, Mayer J, Ong CW, Toma M. Transformative potential of AI in healthcare: definitions, applications, and navigating the ethical landscape and public perspectives. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(2):125. doi:10.3390/healthcare12020125

2.Alowais SA, Alghamdi SS, Alsuhebany N, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):689. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04698-z

3.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

4.Hekler A, Utikal JS, Enk AH, et al. Superior skin cancer classification by the combination of human and artificial intelligence. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:114-121. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.07.019

5.Knackstedt C, Bekkers SC, Schummers G, et al. Fully automated versus standard tracking of left ventricular ejection fraction and longitudinal strain: the FAST-EFs multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(13):1456-1466. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.052

6.Narula S, Shameer K, Salem Omar AM, Dudley JT, Sengupta PP. Machine-learning algorithms to automate morphological and functional assessments in 2D echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(21):2287-2295. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.062

7.Nussinov R, Zhang M, Liu Y, Jang H. AlphaFold, artificial intelligence (AI), and allostery. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(34):6372-6383. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c04346

8.Chen Q, Leaman R, Allot A, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Action: Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic with Natural Language Processing. Annu Rev Biomed Data Sci. 2021;4:313-339. doi:10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-021821-061045.

9.Knott TG, Robinson C. The secA inhibitor, azide, reversibly blocks the translocation of a subset of proteins across the chloroplast thylakoid membrane. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(11):7843-7846.

10.Perivolaris A, Adams-McGavin C, Madan Y, et al. Quality of interaction between clinicians and artificial intelligence systems. a systematic review. Future Healthc J. 2024;11(3):100172. doi:10.1016/j.fhj.2024.100172

11.Asan O, Bayrak AE, Choudhury A. Artificial intelligence and human trust in healthcare: focus on clinicians. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e15154. doi:10.2196/15154

12.Murdoch B. Privacy and artificial intelligence: challenges for protecting health information in a new era. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12910-021-00687-3

13.Paranjape K, Schinkel M, Nannan Panday R, Car J, Nanayakkara P. Introducing artificial intelligence training in medical education. JMIR Med Educ. 2019;5(2):e16048. doi:10.2196/16048

14.Davis MP, Hui D. Quality of life in palliative care. Expert Rev Qual Life Cancer Care. 2017;2(6):293-302. doi:10.1080/23809000.2017.1400911

15.Howell DA, McCaughan D, Smith AG, Patmore R, Roman E. Incurable but treatable: understanding, uncertainty and impact in chronic blood cancers-a qualitative study from the UK’s Haematological Malignancy Research Network. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263672. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263672

16.Black GB, Boswell L, Harris J, Whitaker KL. What causes delays in diagnosing blood cancers? a rapid review of the evidence. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2023;24:e26. doi:10.1017/S1463423623000129

17.Wilson PM, Ramar P, Philpot LM, et al. Effect of an artificial intelligence decision support tool on palliative care referral in hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;66(1):24-32. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.02.317

18.Manz CR, Zhang Y, Chen K, et al. Long-term effect of machine learning-triggered behavioral nudges on serious illness conversations and end-of-life outcomes among patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(3):414-418. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.6303

19.Lee RY, Kross EK, Torrence J, et al. Assessment of natural language processing of electronic health records to measure goals-of-care discussions as a clinical trial outcome. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231204. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1204

20.Liu JH, Shih CY, Huang HL, et al. Evaluating the potential of machine learning and wearable devices in end-of-life care in predicting 7-day death events among patients with terminal cancer: cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e47366. doi:10.2196/47366

21.Kwon DH, Trihy L, Darvish N, et al. Patients can administer mobile audio recordings to increase knowledge in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2024;13(22):e70433. doi:10.1002/cam4.70433

22.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13(8):715-724. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009

23.Kamdar M, Jethwani K, Centi AJ, et al. A digital therapeutic application (ePAL) to manage pain in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;68(3):261-271. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2024.05.033

24.Casarin S, Haelterman NA, Machol K. Transforming personalized chronic pain management with artificial intelligence: a commentary on the current landscape and future directions. Exp Neurol. 2024;382:114980. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114980

25.Snijders RAH, Brom L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer 2022: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):591. doi:10.3390/cancers15030591

26.Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273-e283. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023

27.Shah N, Qazi R, Chu XP. Unraveling the tapestry of pain: a comprehensive review of ethnic variations, cultural influences, and physiological mechanisms in pain management and perception. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e60692. doi:10.7759/cureus.60692

28.Salama V, Godinich B, Geng Y, et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;68(6):e462-e490. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2024.07.025

29.Cascella M, Schiavo D, Cuomo A, et al. Artificial intelligence for automatic pain assessment: research methods and perspectives. Pain Res Manag. 2023;2023:6018736. doi:10.1155/2023/6018736

30.Zhang M, Zhu L, Lin SY, et al. Using artificial intelligence to improve pain assessment and pain management: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023;30(3):570-587. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocac231

31.Masukawa K, Aoyama M, Yokota S, et al. Machine learning models to detect social distress, spiritual pain, and severe physical psychological symptoms in terminally ill patients with cancer from unstructured text data in electronic medical records. Palliat Med. 2022;36(8):1207-1216. doi:10.1177/02692163221105595

32.Shatte ABR, Hutchinson DM, Teague SJ. Machine learning in mental health: a scoping review of methods and applications. Psychol Med. 2019;49(9):1426-1448. doi:10.1017/S0033291719000151

33.Liu Z, Peach RL, Lawrance EL, Noble A, Ungless MA, Barahona M. Listening to mental health crisis needs at scale: using natural language processing to understand and evaluate a mental health crisis text messaging service. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:779091. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.779091

34.Huang Y, Kabir MA, Upadhyay U, Dhar E, Uddin M, Syed-Abdul S. Exploring the potential use of wearable devices as a prognostic tool among patients in hospice care. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(12):1824. doi:10.3390/medicina58121824

35.Huang C, Clayton EA, Matyunina LV, et al. Machine learning predicts individual cancer patient responses to therapeutic drugs with high accuracy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16444. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-34753-5

36.Han K, Cao P, Wang Y, et al. A review of approaches for predicting drug-drug interactions based on machine learning. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:814858. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.814858

37.Liu JYH, Rudd JA. Predicting drug adverse effects using a new Gastro-Intestinal Pacemaker Activity Drug Database (GIPADD). Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6935. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33655-5

38.Biller-Andorno N, Biller A. Algorithm-aided prediction of patient preferences - an ethics sneak peek. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1480-1485. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1904869

39.Biller-Andorno N, Ferrario A, Joebges S, et al. AI support for ethical decision-making around resuscitation: proceed with care. J Med Ethics. 2022;48(3):175-183. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106786

40.Ferrario A, Gloeckler S, Biller-Andorno N. Ethics of the algorithmic prediction of goal of care preferences: from theory to practice. J Med Ethics. 2023;49(3):165-174. doi:10.1136/jme-2022-108371

41.Ghazal KY, Singh Beniwal S, Dhingra A. Assessing telehealth in palliative care: a systematic review of the effectiveness and challenges in rural and underserved areas. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e68275. doi:10.7759/cureus.68275

42.Imam SN, Braun UK, Garcia MA, Jackson LK. Evolution of telehealth-its impact on palliative care and medication management. Pharmacy (Basel). 2024;12(2):61. doi:10.3390/pharmacy12020061

43.Sasaki K, Jabbour EJ, Ravandi F, et al. The LEukemia Artificial Intelligence Program (LEAP) in chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: a model to improve patient outcomes. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(2):241-250. doi:10.1002/ajh.26047

44.Arabyarmohammadi S, Leo P, Viswanathan VS, et al. Machine learning to predict risk of relapse using cytologic image markers in patients with acute myeloid leukemia posthematopoietic cell transplantation. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2022;6:e2100156. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00156

45.Duchmann M, Wagner-Ballon O, Boyer T, et al. Machine learning identifies the independent role of dysplasia in the prediction of response to chemotherapy in AML. Leukemia. 2022;36(3):656-663. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01435-7

46.Ko BS, Wang YF, Li JL, et al. Clinically validated machine learning algorithm for detecting residual diseases with multicolor flow cytometry analysis in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. EBioMedicine. 2018;37:91-100. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.042

47.Zhang W, Peng J, Zhao S, et al. Deep learning combined with radiomics for the classification of enlarged cervical lymph nodes. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148(10):2773-2780. doi:10.1007/s00432-022-04047-5

48.Bobée V, Drieux F, Marchand V, et al. Combining gene expression profiling and machine learning to diagnose B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(5):59. doi:10.1038/s41408-020-0322-5

49.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002;8(1):68-74. doi:10.1038/nm0102-68

50.Hussain Z, De Brouwer E, Boiarsky R, et al. Joint AI-driven event prediction and longitudinal modeling in newly diagnosed and relapsed multiple myeloma. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):200. doi:10.1038/s41746-024-01189-3

51.Sachpekidis C, Enqvist O, Ulen J, et al. Application of an artificial intelligence-based tool in [18F]FDG PET/CT for the assessment of bone marrow involvement in multiple myeloma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(12):3697-3708. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06339-5

52.McCurdy SR, Radojcic V, Tsai HL, et al. Signatures of GVHD and relapse after posttransplant cyclophosphamide revealed by immune profiling and machine learning. Blood. 2022;139(4):608-623. doi:10.1182/blood.2021013054

53.Gandelman JS, Byrne MT, Mistry AM, et al. Machine learning reveals chronic graft-versus-host disease phenotypes and stratifies survival after stem cell transplant for hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2019;104(1):189-196. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.193441

54.Yadav DP, Kumar D, Jalal AS, Kumar A, Singh KU, Shah MA. Morphological diagnosis of hematologic malignancy using feature fusion-based deep convolutional neural network. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16988. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-44210-7

55.Dasariraju S, Huo M, McCalla S. Detection and classification of immature leukocytes for diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia using random forest algorithm. Bioengineering (Basel). 2020;7(4):120. doi:10.3390/bioengineering7040120

56.El Alaoui Y, Padmanabhan R, Elomri A, Qaraqe MK, El Omri H, Yasin Taha R. An artificial intelligence-based diagnostic system for acute lymphoblastic leukemia detection. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2023;305:265-268. doi:10.3233/SHTI230479

57.Lee M, Sy CE, Mesina F, et al. Acute leukemia diagnosis through AI-enhanced attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of peripheral blood smears. Appl Spectrosc. 2025;79(6):967-985. doi:10.1177/00037028241303526

58.Cheng FM, Lo SC, Lin CC, et al. Deep learning assists in acute leukemia detection and cell classification via flow cytometry using the acute leukemia orientation tube. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8350. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58580-z

59.Hauser RG, Esserman D, Beste LA, et al. A machine learning model to successfully predict future diagnosis of chronic myelogenous leukemia with retrospective electronic health records data. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156(6):1142-1148. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqab086

60.Miyoshi H, Sato K, Kabeya Y, et al. Deep learning shows the capability of high-level computer-aided diagnosis in malignant lymphoma. Lab Invest. 2020;100(10):1300-1310. doi:10.1038/s41374-020-0442-3

61.Achi HE, Belousova T, Chen L, et al. Automated diagnosis of lymphoma with digital pathology images using deep learning. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2019;49(2):153-160.

62.Syrykh C, Abreu A, Amara N, et al. Accurate diagnosis of lymphoma on whole-slide histopathology images using deep learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:63. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-0272-0

63.Li D, Bledsoe JR, Zeng Y, et al. A deep learning diagnostic platform for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with high accuracy across multiple hospitals. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6004. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19817-3

64.Yan W, Shi H, He T, et al. Employment of artificial intelligence based on routine laboratory results for the early diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:608191. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.608191

65.Takahashi MES, Mosci C, Souza EM, et al. Proposal for a quantitative (18)F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameter to assess the intensity of bone involvement in multiple myeloma. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16429. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-52740-2

66.Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, Nandurkar H, Philip J. The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: a cross-sectional observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(3):432-442. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.008

67.McGrath P, Holewa H. Special considerations for haematology patients in relation to end-of-life care: Australian findings. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16(2):164-171. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00745.x

68.Shajari S, Kuruvinashetti K, Komeili A, Sundararaj U. The emergence of AI-based wearable sensors for digital health technology: a review. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23(23):9498. doi:10.3390/s23239498

69.Yu KH, Beam AL, Kohane IS. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(10):719-731. doi:10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z

70.Chen Y, Hu X, Zhu Y, Liu X, Yi B. Real-time non-invasive hemoglobin prediction using deep learning-enabled smartphone imaging. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024;24(1):187. doi:10.1186/s12911-024-02585-1

71.Levi R, Carli F, Arévalo AR, et al. Artificial intelligence-based prediction of transfusion in the intensive care unit in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021;28(1):e100245. doi:10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100245

72.Rafiei A, Moore R, Choudhary T, et al. Robust meta-model for predicting the likelihood of receiving blood transfusion in non-traumatic intensive care unit patients. Health Data Sci. 2024;4:0197. doi:10.34133/hds.0197

73.Robinson CL, D’Souza RS, Yazdi C, et al. Reviewing the potential role of artificial intelligence in delivering personalized and interactive pain medicine education for chronic pain patients. J Pain Res. 2024;17:923-929. doi:10.2147/JPR.S439452

74.El-Tallawy SN, Pergolizzi JV, Vasiliu-Feltes I, et al. Incorporation of "Artificial Intelligence" for Objective Pain Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2024;13(3):293-317. doi:10.1007/s40122-024-00584-8.

75.Islam KR, Prithula J, Kumar J, et al. Machine learning-based early prediction of sepsis using electronic health records: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(17):5658. doi:10.3390/jcm12175658

76.Du X, Min J, Shah CP, Bishnoi R, Hogan WR, Lemas DJ. Predicting in-hospital mortality of patients with febrile neutropenia using machine learning models. Int J Med Inform. 2020;139:104140. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104140

77.Alanazi A, Aldakhil L, Aldhoayan M, Aldosari B. Machine learning for early prediction of sepsis in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(7):1276. doi:10.3390/medicina59071276

78.Odeyemi YE, Lal A, Barreto EF, et al. Early machine learning prediction of hospitalized patients at low risk of respiratory deterioration or mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: derivation and validation of a multivariable model. Biomol Biomed. 2024;24(2):337-345. doi:10.17305/bb.2023.9754

79.Janssen RJ, Mourão-Miranda J, Schnack HG. Making individual prognoses in psychiatry using neuroimaging and machine learning. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3(9):798-808. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.04.004

80.Teferra BG, Rueda A, Pang H, et al. Screening for depression using natural language processing: literature review. Interact J Med Res. 2024;13:e55067. doi:10.2196/55067

81.Ryvicker M, Barron Y, Song J, et al. Using natural language processing to identify home health care patients at risk for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Appl Gerontol. 2024;43(10):1461-1472. doi:10.1177/07334648241242321

82.Kurniawan MH, Handiyani H, Nuraini T, Hariyati RTS, Sutrisno S. A systematic review of artificial intelligence-powered (AI-powered) chatbot intervention for managing chronic illness. Ann Med. 2024;56(1):2302980. doi:10.1080/07853890.2024.2302980

83.Aggarwal A, Tam CC, Wu D, Li X, Qiao S. Artificial intelligence-based chatbots for promoting health behavioral changes: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e40789. doi:10.2196/40789

84.Ram M, Afrash MR, Moulaei K, et al. Application of artificial intelligence in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) disease prediction and management: a scoping review. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):1026. doi:10.1186/s12885-024-12764-y

85.Bernardi S, Vallati M, Gatta R. Artificial intelligence-based management of adult chronic myeloid leukemia: where are we and where are we going? Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(5):848. doi:10.3390/cancers16050848

86.Parekh AE, Shaikh OA, Simran, Manan S, Hasibuzzaman MA. Artificial intelligence (AI) in personalized medicine: AI-generated personalized therapy regimens based on genetic and medical history: short communication. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(11):5831-5833. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000001320

87.Hill HA, Jain P, Ok CY, et al. Integrative prognostic machine learning models in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Res Commun. 2023;3(8):1435-1446. doi:10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-23-0083

88.Karathanasis N, Spyrou GM. Predicting the progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic multiple myeloma and stage classification using gene expression data. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(2):332. doi:10.3390/cancers17020332

89.Jacobsen M, Gholamipoor R, Dembek TA, et al. Wearable based monitoring and self-supervised contrastive learning detect clinical complications during treatment of hematologic malignancies. NPJ Dig Med. 2023;6(1):105. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00847-2

90.Cohen O, Barzilai M. AI applications in transfusion medicine: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Acta Haematol. 2025;148(5):516-526. doi:10.1159/000546303

91.Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44-56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

92.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised International Staging System for multiple myeloma: a report from international myeloma working group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(26):2863-2869. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2267

93.Bataller A, Garrido A, Guijarro F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2017 risk stratification for acute myeloid leukemia: validation in a risk-adapted protocol. Blood Adv. 2022;6(4):1193-1206. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005585

94.Merdan S, Subramanian K, Ayer T, et al. Gene expression profiling-based risk prediction and profiles of immune infiltration in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(1):2. doi:10.1038/s41408-020-00404-0

95.Herrera AF, McCord R, Kimes P, et al. Risk profiling of patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by measuring circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA): results from the POLARIX study. Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1):1297-1300. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-157559

96. Lipkova J, Chen RJ, Chen B, et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(10):1095-1110. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2022.09.012

97.Eckardt JN, Röllig C, Metzeler K, et al. Prediction of complete remission and survival in acute myeloid leukemia using supervised machine learning. Haematologica. 2023;108(3):690-704. doi:10.3324/haematol.2021.280027

98.Guarnera L, Visconte V. Using machine learning to unravel the intricacy of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2024;109(4):1025-1026. doi:10.3324/haematol.2023.284085

99.Santiago R, Ortiz Jimenez J, Forghani R, et al. CT-based radiomics model with machine learning for predicting primary treatment failure in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(10):101188. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101188

100.Chen J, Lin F, Dai Z, et al. Survival prediction in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: multimodal PET/CT deep features radiomic model utilizing automated machine learning. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(10):452. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-05905-0

101.Choe H, Yuhasz N, Miller GE, et al. Advanced machine learning techniques to predict GVHD occurrence and severity with high accuracy. Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1):7658-7659. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-167454

102.Rowley SD, Gunning TS, Pelliccia M, et al. Using targeted transcriptome and machine learning of pre- and post-transplant bone marrow samples to predict acute graft-versus-host disease and overall survival after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(7):1357. doi:10.3390/cancers16071357

103.He Q, Li X, Fang Y, Kong F, Yu Z, Xie L. Two machine learning-derived nomogram for predicting the occurrence and severity of acute graft-versus-host disease: a retrospective study based on serum biomarkers. Front Genet. 2024;15:1421980. doi:10.3389/fgene.2024.1421980

104.Tsang M, LeBlanc TW. Palliative and end-of-life care in hematologic malignancies: progress and opportunities. JCO Oncol Pract. 2024;20(6):739-741. doi:10.1200/OP.24.00081

105.Oikonomou EK, Sangha V, Dhingra LS, et al. Artificial intelligence-enhanced risk stratification of cancer therapeutics-related cardiac dysfunction using electrocardiographic images. medRxiv. 2024;2024.24304047. doi:10.1101/2024.03.12.24304047

106.Al-Droubi SS, Jahangir E, Kochendorfer KM, et al. Artificial intelligence modelling to assess the risk of cardiovascular disease in oncology patients. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2023;4(4):302-315. doi:10.1093/ehjdh/ztad031

107.Aziz F, Bianchini D, Olawade DB, Boussios S. The impact of AI-driven remote patient monitoring on cancer care: a systematic review. Anticancer Res. 2025;45(2):407-418. doi:10.21873/anticanres.17430

108.Tabataba Vakili S, Haywood D, Kirk D, et al; Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Survivorship Study Group. Application of artificial intelligence in symptom monitoring in adult cancer survivorship: a systematic review. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2024;8:e2400119. doi:10.1200/CCI.24.00119

109.He JC, Moffat GT, Podolsky S, et al. Machine learning to allocate palliative care consultations during cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(14):1625-1634. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.01291

110.Blanes-Selva V, Ruiz-García V, Tortajada S, Benedí JM, Valdivieso B, García-Gómez JM. Design of 1-year mortality forecast at hospital admission: a machine learning approach. Health Informatics J. 2021;27(1):1460458220987580. doi:10.1177/1460458220987580

111.Clark M, Bailey S. Chatbots in Health Care: Connecting Patients to Information: Emerging Health Technologies. CADTH Horizon Scans; 2024.

112.Kolla L, Parikh RB. Uses and limitations of artificial intelligence for oncology. Cancer. 2024;130(12):2101-2107. doi:10.1002/cncr.35307

113.Istasy P, Lee WS, Iansavichene A, et al. The impact of artificial intelligence on health equity in oncology: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e39748. doi:10.2196/39748

114. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. doi:10.1126/science.aax2342

115. Pham T. Ethical and legal considerations in healthcare AI: innovation and policy for safe and fair use. R Soc Open Sci. 2025;12(5):241873. doi:10.1098/rsos.241873

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.