3 Things You Should Know About Managing ALK+ Metastatic NSCLC

Multidisciplinary approaches, RNA-based next-generation sequencing, and patient-specific front-line treatment decisions are all important for curating effective NSCLC treatments.

The authors

RELEASE DATE: March 1, 2025

EXPIRATION DATE: March 1, 2026

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon successful completion of this activity, you should be better prepared to:

• Interpret molecular testing results accurately to guide the selection of targeted therapies in the first-line setting.

• Identify key patient characteristics, including comorbidities, disease stage, and molecular profiles, that influence treatment decisions in ALK+ metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

• Apply evidence-based guidelines to select appropriate first-line therapies based on individual patient characteristics.

• Evaluate clinical evidence supporting the use of LCT in combination with chemotherapy for ALK+ mNSCLC.

Accreditation/Credit Designation

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Off-label disclosure/disclaimer

This activity may or may not discuss investigational, unapproved, or off-label use of drugs. Learners are advised to consult prescribing information for any products discussed. The information provided in this activity is for accredited continuing education purposes only and is not meant to substitute for the independent clinical judgment of a health care professional relative to diagnostic, treatment, or management options for a specific patient’s medical condition. The opinions expressed in the content are solely those of the individual faculty members, and do not reflect those of PER or any company that provided commercial support for this activity.

Instructions for participation/how to receive credit

- Read this activity in its entirety.

- Go to https://www.gotoper.com/nyl25alk-postref to access and complete the posttest.

- Answer the evaluation questions.

- Request credit using the drop-down menu.

YOU MAY IMMEDIATELY DOWNLOAD YOUR CERTIFICATE.

Approximately 4% to 5% of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases are positive for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutations.1 For patients with metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC, the emergence of second- and third-generation ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has improved outcomes and transformed treatment. Key components of care include appropriate molecular testing, implementation of evidence-based treatment sequencing strategies, and integration of multidisciplinary care. Here are 3 things you should know about managing metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC.

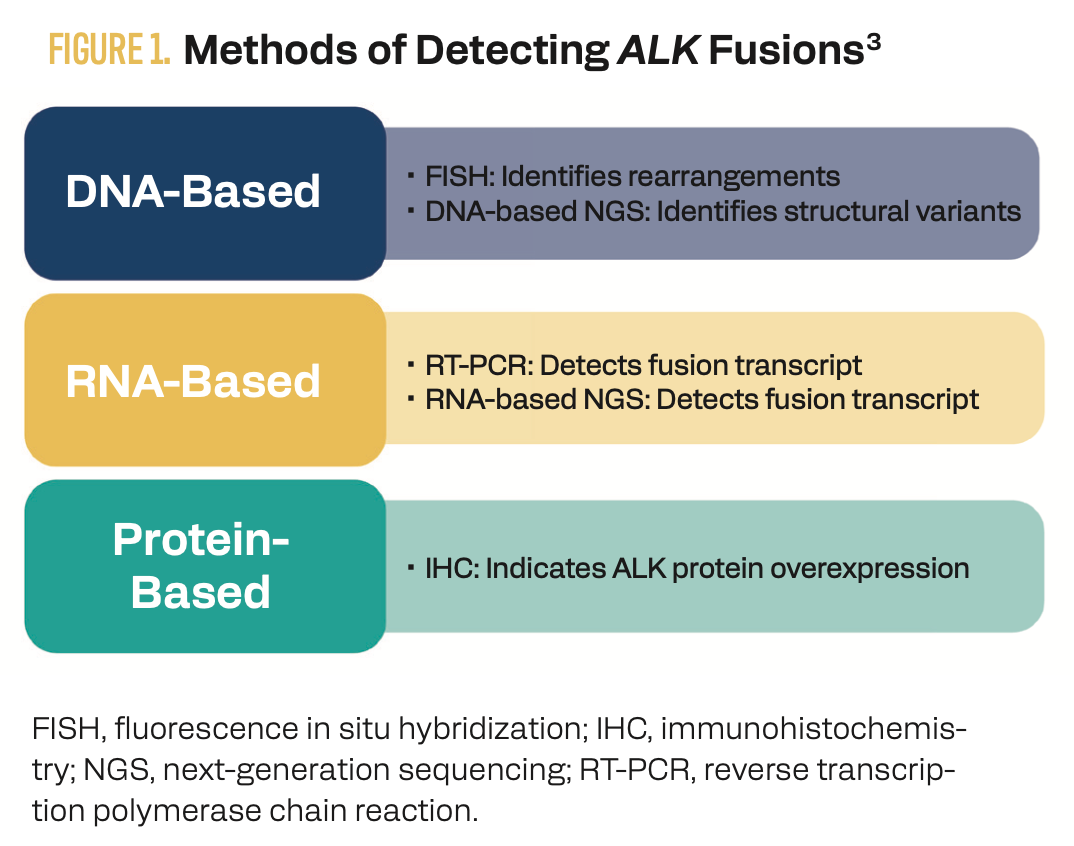

1. RNA-based NGS is recommended for ALK fusion detection.

Appropriate molecular testing is critical for identifying mutations early and informing treatment decisions in metastatic NSCLC. Most ALK mutations are a result of a translocation and fusion with another gene (frequently EML4 in NSCLC), causing overexpression of the ALK tyrosine kinase.2 Previously, the standard methods of diagnosing ALK-mutated NSCLC were single-gene assays, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization, or immunohistochemistry for detecting ALK protein expression.3 However, insufficient tissue sample availability and an inability to detect less common mutations are limitations of these methods (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methods of Detecting ALK Fusions

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is increasingly being used to identify actionable biomarkers because multiple mutations can be evaluated from a single sample.4 NCCN guidelines recommend a comprehensive panel-based approach for molecular and biomarker analysis, specifically RNA-based NGS for maximizing the detection of fusion events.5

Although DNA-based NGS panels can detect a broad range of genetic mutations, these tests are limited in the detection of fusions. Large intronic regions between fusion partners can result in false negatives with DNA-based testing; however, RNA sequencing detects fusions at the transcript level and is therefore not compromised by large introns.6 RNA sequencing can also identify multiple gene fusions or previously unidentified fusions. In a study of 254 tissue samples that tested negative for driver mutations using a DNA-based NGS test, 36 samples (14%) were subsequently identified by an RNA-based NGS panel as having an alteration, with 33 being actionable alterations (including 11% with ALK fusions).7

2. Optimal first-line treatment is dependent on patient-specific factors.

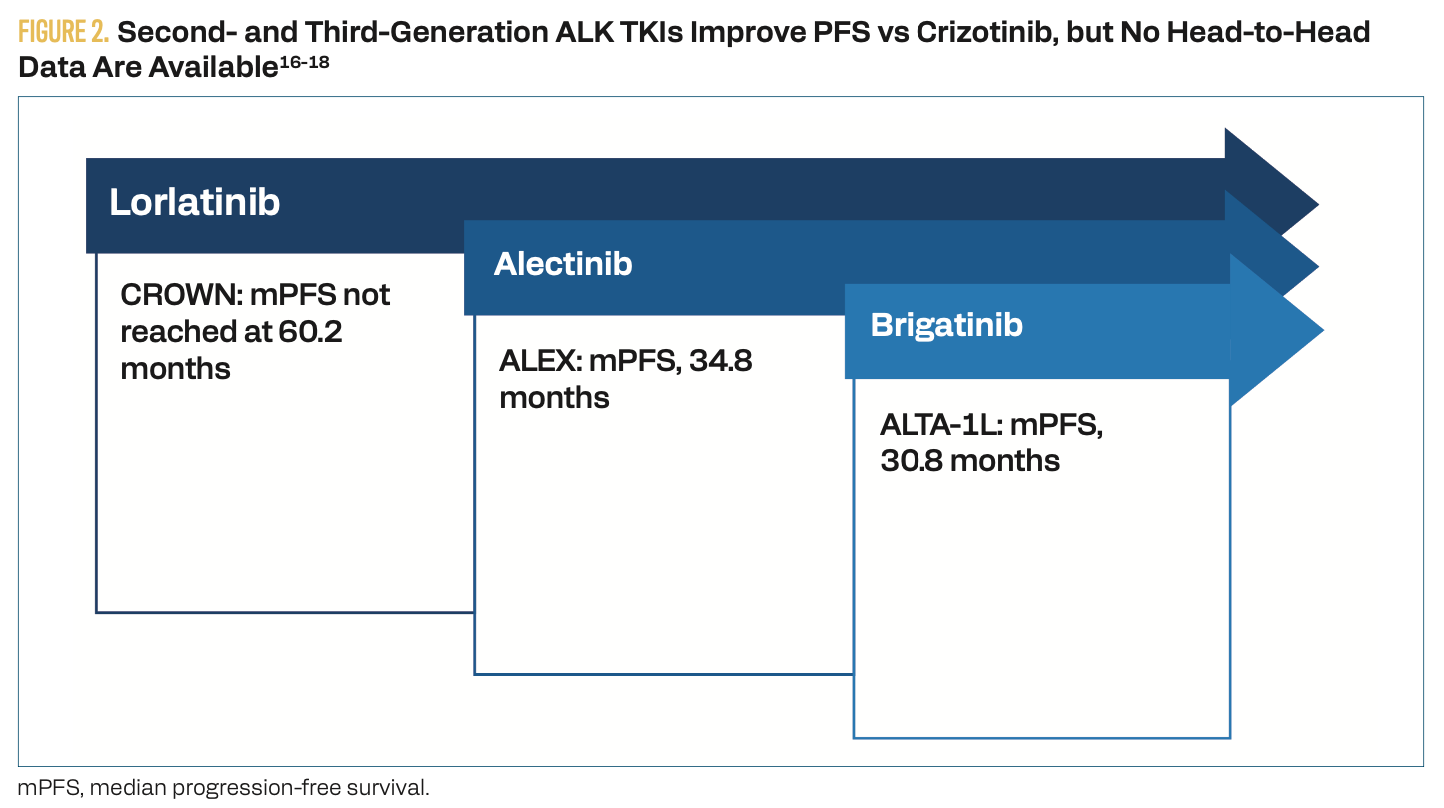

Crizotinib is a first-generation ALK TKI that was shown to improve progression-free survival (PFS) compared with chemotherapy (CT); however, most patients develop resistance to crizotinib within 1 to 2 years, leading to the development of second-generation ALK TKIs.8 In clinical trials, alectinib, brigatinib, and ensartinib have all demonstrated improved PFS compared with crizotinib.9-11 As a result, NCCN guidelines recommend treatment with alectinib, brigatinib, ensartinib, or the third-generation TKI lorlatinib as the preferred first-line options in patients with metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC.5 Lorlatinib improved PFS relative to crizotinib (78% vs 39%; HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.19-0.41, P < .0001) in the phase 3 CROWN trial (NCT03052608).12

Because patients with ALK-positive NSCLC have an increased risk for brain metastases, newer TKIs are also designed to improve central nervous system (CNS) penetration.13 Notably, lorlatinib demonstrated an intracranial overall response rate (ORR) of 82% vs 23% with crizotinib in the CROWN trial (Figure 2). A duration of intracranial response of at least 12 months was seen in 79% of patients in the lorlatinib arm vs 0% in the crizotinib arm.12

Figure 3. Second- and Third-Generation ALK TKIs Improve PFS vs Crizotinib, but no Head-to-Head Data are Available

In addition to CNS penetration, treatment selection is influenced by safety profiles and patient characteristics, such as ECOG status and comorbidities.14 Optimal sequencing of ALK TKIs has not been established, as the question remains whether to use the third-generation lorlatinib as first-line therapy or reserve it as salvage therapy following progression on a second-generation agent. Although lorlatinib is more CNS penetrant, it is associated with a suboptimal safety profile compared with first- and second-generation agents.15 Adverse effects include lipid abnormalities, edema, peripheral neuropathy, and cognitive impairment.

Although newer agents have improved outcomes, most patients with an initial response to ALK TKIs will develop resistance.16-18 Therefore, the use of local consolidative therapy (LCT) is being studied as a means of eliminating residual disease and delaying resistance. The BRIGHTSTAR trial (NCT03707938) assessed the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of the combined use of brigatinib with LCT (radiation, surgery, or surgery and radiation) in patients with TKI-naive, ALK-positive NSCLC.19 Combination therapy resulted in a 100% disease control rate and a 79% ORR. At 3 years, the PFS was 66%, with limited metastatic burden at baseline and negative liquid biopsy at diagnosis as predictors of better PFS.

3. A multidisciplinary approach can improve outcomes in ALK-positive NSCLC.

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) plays a key role in optimizing care for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC. Because metastatic NSCLC may be treated with surgery, radiotherapy, ablation, CT, and/or targeted therapy, the use of an MDT allows for multiple treatment opinions and a more comprehensive evaluation to improve patient outcomes (Figure 3).20 With the increasing number of targeted treatment options, discussion of optimal treatment timing and sequencing of therapies is also critical. NCCN guidelines recommend that patients be evaluated in a multidisciplinary setting when more than 1 treatment modality is being considered.5

Figure 3. Specialists Involved in an MDT

As previously described, in the BRIGHTSTAR study, the combined use of targeted medical therapy with LCT using surgery, radiotherapy, or both improved PFS in patients with TKI-naive disease.19 Using a combination approach up front can improve outcomes and requires coordination of care across multiple specialties. The BRIGHTSTAR-2 trial (NCT06522360), which is currently recruiting, will compare outcomes in 3 different treatment arms—brigatinib monotherapy, brigatinib plus CT, or brigatinib plus LCT.21

Potential barriers to the use of MDT include specialists at multiple sites, which may be alleviated using virtual tumor boards.22 Additionally, tumor boards should include regular cross-specialty case reviews to allow for discussion of complex medical oncology cases in addition to earlier-stage disease and local treatments.

Key References

3. Hernandez S, Conde E, Alonso M, et al. A narrative review of methods for the identification of ALK fusions in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2023;12(7):1549-1562. doi:10.21037/tlcr-22-855

12. Shaw AT, Bauer TM, de Marinis F, et al. First-line lorlatinib or crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2018-2029. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027187

19. Elamin Y, Gandhi S, Saad M, et al. OA22.04 BRIGHTSTAR local consolidative therapy with brigatinib in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naïve ALK-rearranged metastatic NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18(suppl 11):S96. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2023.09.109

For full list of references, visit

www.gotoper.com/nyl25alk-postref

CME Posttest Questions

1. Which of the following tests is considered the gold standard for detecting ALK fusions?

A. FISH

B. IHC

C. DNA-based NGS

D. RNA-based NGS

2. Which frontline therapy would you expect to elicit the most favorable PFS and intracranial activity for a 62-year-old patient with newly diagnosed, advanced ALK+ NSCLC and brain metastases?

A. Crizotinib

B. Pembrolizumab

C. Lorlatinib

D. Carboplatin and pemetrexed

3. Based on positive findings from the BRIGHTSTAR trial, which ALK+ NSCLC patient profile would you expect to have the most favorable PFS outcome from brigatinib and local consolidation therapy (LCT)?

A. Positive liquid biopsy at diagnosis; single liver metastasis; complete LCT to the primary tumor only; ECOG 1; no prior treatment

B. Negative liquid biopsy at diagnosis; single liver metastasis; complete LCT;

ECOG 1; no prior treatment

C. No liquid biopsy taken at diagnosis; single contralateral lung metastasis; partial LCT to primary tumor; ECOG 1; no prior treatment

D. Negative liquid biopsy at diagnosis; brain, liver, and bone metastases; complete LCT to all metastatic sites; ECOG 1; no prior treatment

To learn more about this topic, including a case-based discussion on optimal management of advanced ALK-positive NSCLC, go to https://www.gotoper.com/nyl25alk-activity

CME Provider Contact information

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC

2 Commerce Drive, Suite 110, Cranbury, NJ 08512

Toll-Free: 888-949-0045

Local: 609-378-3701

Fax: 609-257-0705

info@gotoper.com