3 Things You Should Know About Treating Epithelioid Sarcoma

Epithelioid sarcoma is individualized based on disease characteristics, it's methods of treatment vary, and systemic treatment is both targeted medication and chemotherapy.

The authors

RELEASE DATE: March 1, 2025

EXPIRATION DATE: March 1, 2026

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon successful completion of this activity, you should be better prepared to:

•Identify epithelioid sarcoma through recognition of its unique features

•Recognize when to refer patients with epithelioid sarcoma to specialized academic centers, and discuss the importance of clinical trials in developing and providing access to emerging therapies

Accreditation/Credit Designation

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Acknowledgment of commercial support

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc.

Off-label disclosure/disclaimer

This activity may or may not discuss investigational, unapproved, or off-label use of drugs. Learners are advised to consult prescribing information for any products discussed. The information provided in this activity is for accredited continuing education purposes only and is not meant to substitute for the independent clinical judgment of a health care professional relative to diagnostic, treatment, or management options for a specific patient’s medical condition. The opinions expressed in the content are solely those of the individual faculty members, and do not reflect those of PER or any company that provided commercial support for this activity.

Instructions for participation/how to receive credit

1. Read this activity in its entirety.

2. Go to https://www.gotoper.com/oc25esacurps-postref to access and complete the posttest.

3. Answer the evaluation questions.

4. Request credit using the drop-down menu.

YOU MAY IMMEDIATELY DOWNLOAD YOUR CERTIFICATE.

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare form of soft tissue sarcoma (STS) that accounts for fewer than 1% of STS cases.1 The disease is difficult to treat and is associated with high rates of local recurrence (34%-77%) and metastasis (≈ 40%).2 While the general principles of STS management have not shifted significantly in the past couple of decades, there have been advancements in the systemic treatment of ES. Here are 3 things you should know about treating ES.

1. ES treatment is individualized based on disease characteristics and patient factors.

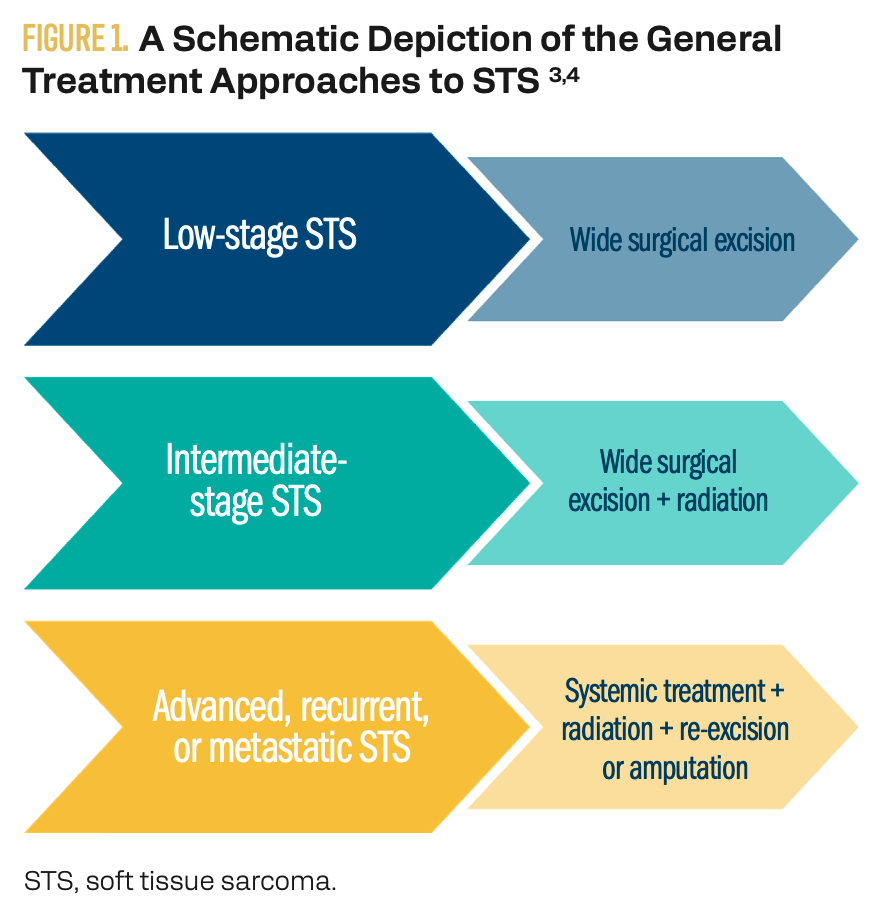

Because ES has high rates of recurrence, its treatment regimens are typically aggressive. Whenever possible, surgical excision of the tumor with the goal of achieving microscopically negative margins is recommended (Figure 1).3,4 Depending on the location and extent of local tumor invasion, limb-sparing surgery may or may not be feasible, with amputation being the alternative. Perioperative radiation treatment of the tumor bed is also recommended in all but the lowest stages of disease. Metastatic and/or recurrent disease is often additionally treated with systemic therapy given as either traditional chemotherapeutic regimens or newer targeted medication.3,4

Figure 1. A Schematic Depiction of the General Treatment Approaches to STS

Developing a treatment plan for ES is a complex and individualized process. Although general guidelines for management exist, patient preferences and lifestyle factors should be considered, particularly for decisions that weigh risk vs benefit (eg, limb salvage vs amputation). A multidisciplinary approach that incorporates shared decision-making and carefully considers the patient’s functional needs prior to initiation is generally recommended.3,4

2. Systemic treatment for ES includes both traditional chemotherapy and targeted medication.

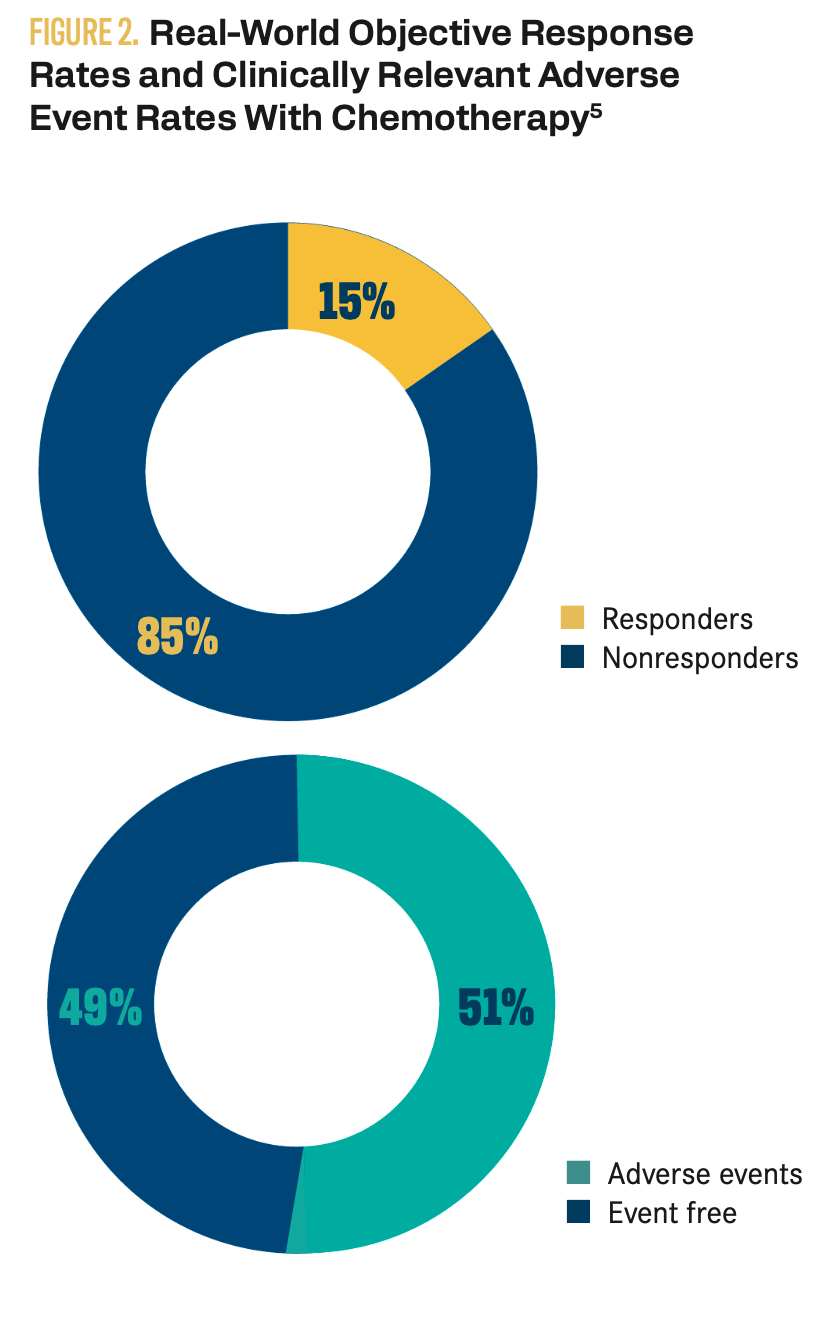

Although the mainstay of ES treatment is surgical excision with perioperative radiation, systemic treatment is sometimes necessary in more advanced cases to prolong survival and minimize the risk of recurrence. Historically, systemic treatment options for patients with advanced ES have been limited to cytotoxic chemotherapies involving the use of anthracyclines, gemcitabine, and/or ifosfamide. However, these treatments have not been particularly successful, with investigators in 2 studies reporting progression-free survival periods ranging from 6 months to 29 weeks and response rates being less than 20%.5,6 Moreover, traditional chemotherapies cause adverse events (AEs) at relatively high rates. For example, Gounder and colleagues found that among 74 patients with advanced or metastatic ES being treated with traditional chemotherapy, over half (51.4%) experienced an AE (Figure 2).5

Figure 2. Real-World Objective Response Rates and Clinically Relevant Adverse Event Rates with Chemotherapy

Fortunately, in recent years, targeted medication for ES has been developed. Tazemetostat was approved by the FDA in 2020 and was granted orphan drug status for the treatment of ES based on outcomes of a phase 2 clinical trial. The study enrolled 62 patients; an objective response rate of 15% was noted, with 26% of patients having disease control at 32 weeks of follow-up.7 Treatment-related AEs of grade 3 or higher included anemia (6%) and weight loss (3%). Results of this study led to NCCN guidelines listing tazemetostat as the preferred treatment for recurrent, metastatic, or locally advanced and unresectable ES.3 Additionally, tazemetostat is still being investigated in combination with doxorubicin as a first-line systemic therapy for advanced ES.8

3. Traditional and targeted chemotherapies used to treat ES vary in their mechanisms and results.

Traditional chemotherapies (eg, anthracyclines, gemcitabine, and/or ifosfamide) historically used to treat ES do not target cancerous cells very specifically. This is due to commonalities in the mechanisms of action of such medications—they each work in some capacity by impairing the process of DNA replication necessary for cell division. This is effective in hindering a tumor’s ability to grow, but it can also have a negative impact on the body’s rapidly dividing cell lines (eg, intestinal epithelial or bone marrow cells). This imprecise targeting leads to many of the hallmark AEs associated with such medications; these include hair loss, immunosuppression, anemia, and nausea. To give another example, anywhere from 5% to 23% of patients treated with anthracyclines will go on to develop heart failure owing to cardiotoxicity.9

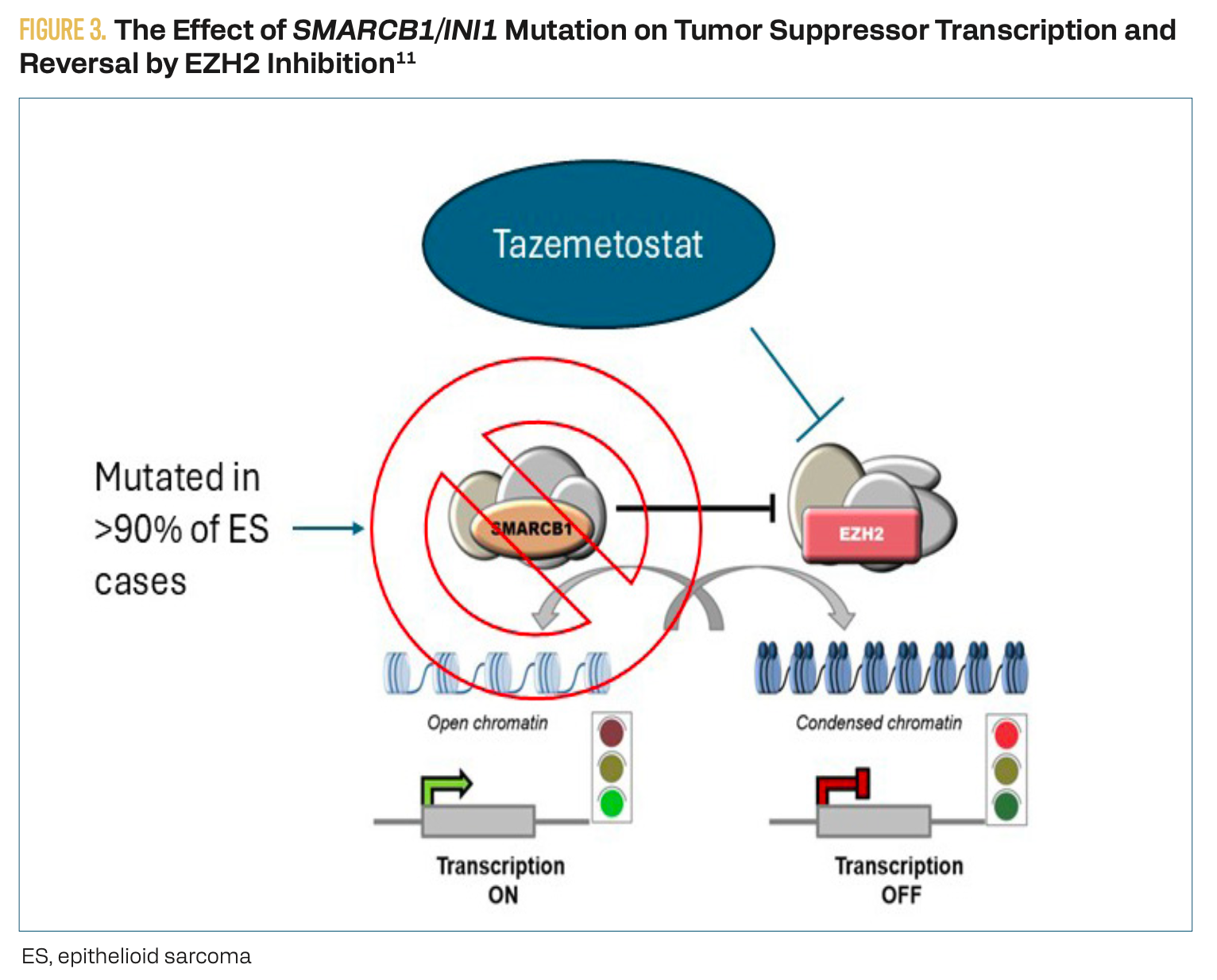

Given the drawbacks of traditional chemotherapies, it is unsurprising that recent oncologic drug developments tend to focus on more precise targeting of cancer cells. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor samples has revealed that over 90% of ES tumors demonstrate a loss of SMARCB1/INI1 function.10 SMARCB1/INI1 is a tumor suppressor that inhibits the enhancer of the EZH2 enzyme, indirectly stimulating the transcription of tumor suppressor genes (Figure 3).11 Based on this genetic and mechanistic background information, EZH2 was identified as a potential target for managing ES. Indeed, outcomes of a clinical trial showed that tazemetostat, the novel inhibitor of EZH2, was a safe and effective treatment for recurrent, metastatic, or locally advanced and unresectable ES.7 Encouraging initial clinical results for tazemetostat alone has led to it being currently investigated for use as part of a combined therapeutic regimen along with doxorubicin.8

Figure 3. The Effect of SMARCB1/INI1 Mutation on Tumor Suppression Transcription and Reversal by EZH2 Inhibition

Key References

- Gounder MM, Merriam P, Ratan R, et al. Real-world outcomes of patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelioid sarcoma. Cancer. 2021;127(8):1311-1317. doi:10.1002/cncr.33365

- Gounder M, Schöffski P, Jones RL, et al. Tazemetostat in advanced epithelioid sarcoma with loss of INI1/SMARCB1: an international, open-label, phase 2 basket study. Lancet Oncol.2020;21(11):1423-1432. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30451-4

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CDM. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(4):542-550. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181882c54

For full reference list visit https://www.gotoper.com/oc25esacurps-postref

CME Posttest Questions

1. Which of the following is the molecular hallmark of epitheliod sarcoma?

A. Alteration of INI-1 and increase in SMARCB1 expression

B. Deletion of SMARCB1 and loss of INI-1 expression

C. Fusion of SMARCB1 and INI-1

D. Mutation of SMARCB1 and increase in INI-1 expression

2. A 35-year-old male patient presents to a community oncology clinic with a firm 2.5-cm lesion on his right elbow. Biopsy confirms a diagnosis of ES, and CT scans show metastases to the axillary lymph nodes. When discussing treatment options with your patient, including chemotherapy and the oral option, tazemetostat, you agree to initiate tazemetostat, but your patient is concerned about side effects. Which of the following are the most common grade 3 or greater TRAEs most likely to occur, according to clinical trial experience?

A.Anemia and weight loss

B. Fatigue and diabetes

C. Increased LFTs and decreased LVEF

D. Pneumonitis and thyroiditis

3. Your 21-year-old male patient is referred to you after an initial consult with an orthopedic surgeon who performed a core needle biopsy on a firm, nonmobile mass on his forearm that gradually increased in size over the last 18 months. MRI results show heterogeneous necrosis indicative of malignancy, but CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is negative for metastatic disease. Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor is positive for CD34, cytokeratin, EMA, and vimentin; it is negative for CD31, S-100, and INI1, confirming the diagnosis of ES. According to current data and guideline recommendations, what is the next best step in managing this patient’s ES at this time?

A. Doxorubicin

B. Gemcitabine plus docetaxel

C. Larotrectinib, 100 mg, given orally twice daily

D. Tazemetostat, 800 mg, given orally twice daily

Claim Your CME Credit at https://www.gotoper.com/oc25esacurps-postref

To learn more about this topic, including information on the pathology and histology of epithelioid sarcoma, go to https://www.gotoper.com/oc25esacurps-activity.

CME Provider Contact information

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC

2 Commerce Drive, Suite 110, Cranbury, NJ 08512

Toll-Free: 888-949-0045

Local: 609-378-3701

Fax: 609-257-0705

info@gotoper.com

Sarcoma Awareness Month 2023 with Brian Van Tine, MD, PhD

August 1st 2023Brian Van Tine, MD, PhD, speaks about several agents and combination regimens that are currently under investigation in the sarcoma space, and potential next steps in research including immunotherapies and vaccine-based treatments.