Expanding Horizons in T-Cell Lymphoma Therapy: Focus on Personalized Treatment Strategies

Several lymphoma experts discuss the current T-cell lymphoma landscape, the need for new therapies, and ongoing research in the space.

Author Titles

Abstract

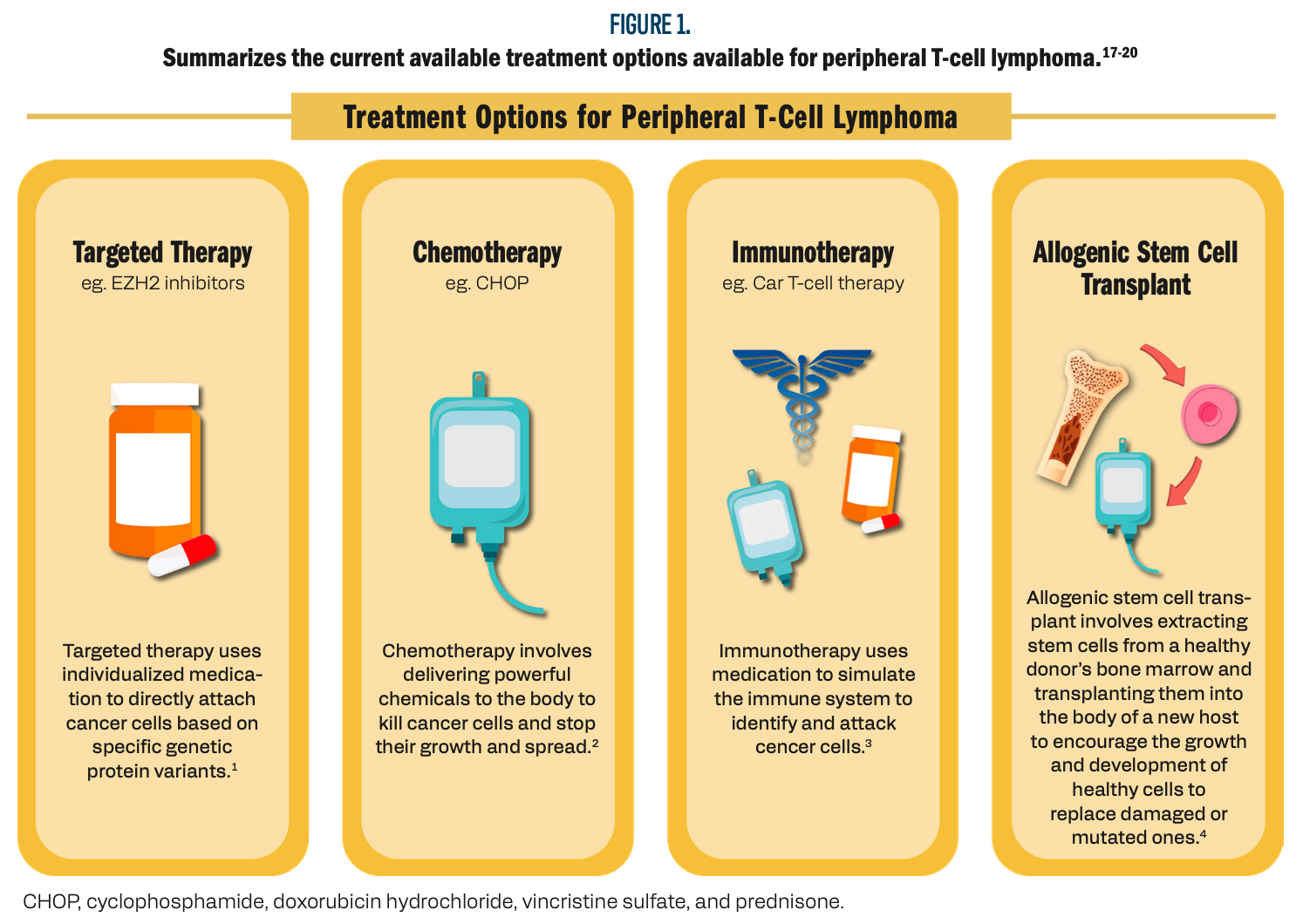

T-cell lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, presents significant treatment challenges due to its diverse subtypes and aggressive progression. Jasmine Zain, MD, drawing on her expertise in chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) T-cell therapies, is focused on expanding therapeutic options for T-cell lymphomas, particularly peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). A critical aspect of treatment development involves recognizing that the subtypes of nodal PTCL are defined by specific genetic pathways, which determine their response to different therapies. This insight has led to the development of more personalized, subtype-specific treatment strategies. Current treatment approaches for PTCL typically involve combinations of chemotherapy, targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. The standard first-line therapy, CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), has relatively low response rates, highlighting the need for more effective alternatives. While stem cell transplantation is beneficial for certain PTCL subtypes, overall outcomes remain inconsistent. Some targeted therapies have shown efficacy in specific subtypes, but many forms of PTCL are still resistant to available treatments, underscoring the need for further research. In cases of relapsed/refractory disease, stem cell transplantation remains the primary treatment option, though it is associated with significant risks and often impacts patients’ quality of life. There is a pressing need for new, less toxic therapies. Several targeted drugs are currently in clinical trials, with the goal of improving treatment options for patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL. Ongoing research into the genetic and molecular characteristics of PTCL aims to develop more individualized therapies that are better suited to each patient’s specific disease profile, offering hope for improved outcomes in this challenging lymphoma subtype.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has emerged as a groundbreaking approach in oncology, specifically targeting hematological malignancies, including T-cell lymphomas. This innovative therapeutic strategy involves the genetic engineering of a patient’s T cells to express CARs that specifically recognize and bind to tumor-associated antigens, ultimately enabling the T cells to eliminate malignant cells.1 The process typically entails the isolation of T cells from a patient’s blood, modification of these cells to express CARs, extensive expansion in vitro, and subsequent reinfusion into the patient to target and destroy cancer cells.1

Despite the promise of CAR T-cell therapy, significant challenges remain, particularly in the treatment of T-cell lymphomas, a group of heterogeneous malignancies that originate from T lymphocytes. T-cell lymphomas, such as peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), are characterized by their aggressive behavior and diverse subtypes, which present unique clinical challenges. PTCL is classified into various subtypes, including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), each defined by distinct genetic mutations and epigenetic alterations.1,2 The prognosis for patients with PTCL is often poor, with limited treatment options available and a median survival of approximately 1 to 2 years.3

Challenges specific to CAR T-cell therapy in T-cell lymphomas include severe toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity, alongside issues such as antigen escape and limited persistence of T cells in the tumor microenvironment.4,5 Additionally, the autologous nature of the therapy restricts accessibility, as just about 20% of patients with T-cell lymphomas qualify for CAR T-cell treatment.6 High costs, manufacturing complexities, and extended production timelines further limit the therapy’s widespread application.7

Jasmine Zain, MD, director of the T-Cell Lymphoma Program at City of Hope in Duarte, California, is at the forefront of addressing these challenges through her research on CAR T-cell therapies in T-cell lymphomas. Her expertise and commitment to advancing this field are critical for developing strategies that enhance the efficacy and accessibility of these potentially lifesaving treatments. Zain’s keynote presentation at MedNews Week delved into the clinical significance of epigenetic components in nodal PTCL, exploring how specific genetic pathways can inform treatment strategies.8,9

Understanding the genetic landscape of nodal PTCL is essential for developing personalized immunotherapeutic approaches. For instance, mutations in genes such as IDH2 and TET2 have been identified as significant prognostic markers, influencing patient outcomes and guiding treatment decisions.10,11 Moreover, current therapeutic approaches for PTCL, which may include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and stem cell transplantation, often have limited efficacy, especially in relapsed/refractory cases.12,13

Ongoing research into novel agents, such as EZH2 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, and HDAC inhibitors, is crucial in exploring new therapeutic avenues for nodal PTCL.14 These agents are undergoing clinical trials and have shown promising results in enhancing treatment outcomes for this challenging lymphoma subtype.15 Furthermore, approved therapies, including pralatrexate, romidepsin, and brentuximab vedotin, have provided some success but highlight the pressing need for continued research and innovation.16

Zain’s presentation will additionally offer valuable insights into the latest advancements in T-cell lymphoma treatment and provide guidance on managing complex clinical cases. By highlighting the challenges and opportunities within this rapidly evolving field, the discussion aims to foster a deeper understanding among health care professionals and researchers. Continued exploration through clinical trials and collaboration in the field is imperative for improving outcomes for patients with T-cell lymphomas, ultimately offering hope for those with limited treatment options (Figure 1)17-20.

Figure 1. Summarizes the current available treatment options available for peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Genetic Pathways and Targeted Therapies in Nodal Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas

The clinical categorization of nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) is primarily driven by specific genetic and molecular pathways. Subtypes such as T-follicular helper (TFH) cell lymphoma, defined by TFH cells, and cases involving IDH2 mutations are examples where genetic markers are crucial for distinguishing among different forms of nodal PTCL. These markers not only aid in diagnosis but also guide therapeutic decisions and help predict patient outcomes.21 A deeper understanding of these pathways is essential for developing targeted therapies aimed at improving survival rates in patients with PTCL.22 Novel therapeutic approaches focusing on epigenetic mutations, cell surface receptors, and the tumor microenvironment have shown promise. These include therapies targeting signaling pathways, kinase inhibitors, and agents inhibiting non-cell signaling pathways.23

Recent advances in epigenetic-targeted therapies, such as EZH2 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, and HDAC inhibitors, have demonstrated efficacy in treating PTCL with epigenetic abnormalities.24 Clinical trials have reported encouraging results, providing new hope for patients with aggressive forms of PTCL.25 By identifying specific molecular aberrations, clinicians can tailor treatment regimens to individual patients, enhancing treatment response and outcomes.25 Additionally, the ongoing investigation of PTCL-not otherwise specified molecular subgroups has opened doors to more personalized treatment approaches, potentially improving outcomes for these patients.25

The TP53 mutation has emerged as a significant prognostic marker in PTCL, with mutations associated with poorer survival.26 Identifying patients with TP53 mutations allows for more accurate prognostication and the opportunity to adjust treatment strategies accordingly.27 In a cohort of 396 patients with PTCL undergoing MSK-IMPACT sequencing, 66% lacked baseline clinical prognostic data, underscoring the need for a comprehensive evaluation for proper risk stratification.28 Among the patients, 141 received cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP)-based treatment, which remains a common first-line regimen despite its limited efficacy in certain subtypes.29 The necessity of improved therapeutic options is further highlighted in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), where the evaluation of molecular biomarkers, including ALK status, has proven instrumental in guiding treatment and predicting outcomes.30

Future research into the genetic markers of PTCL, particularly in understanding the role of epigenetic modifications, holds promise for the development of novel, less toxic therapies. By targeting aberrant gene expression patterns, these therapies have the potential to significantly improve survival outcomes and the quality of life for patients with PTCL.31

Evolving Therapeutic Strategies in T-Cell Lymphoma: From Chemotherapy to Targeted Therapies

Treatment of T-cell lymphomas involves a multifaceted approach, including chemotherapy, targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and stem cell transplantation, all tailored to the specific subtype and individual patient characteristics. The first-line therapy typically consists of combination chemotherapy regimens, such as CHOP or its variants. However, CHOP has shown limited efficacy, with overall response rates ranging from 50% to 70% and progression-free survival (PFS) of less than 2 years in aggressive subtypes, such as angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and PTCL.32,33 These limitations underscore the need for more effective treatment strategies.

Consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in the first complete remission is often employed to eradicate minimal residual disease after induction chemotherapy, aiming to reduce relapse rates and prolong both PFS and overall survival.34 However, this strategy carries significant risks, especially for older patients or those with comorbidities, making patient selection crucial. Research is ongoing to refine the criteria for ASCT and to integrate novel therapies, such as targeted agents and immunotherapies, to improve long-term outcomes.35

The emergence of targeted therapies has significantly changed the treatment landscape for T-cell lymphomas. Brentuximab vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD30, has demonstrated substantial efficacy in CD30-positive subtypes such as ALCL.36 This targeted approach enhances tumor specificity while reducing systemic toxicity compared with traditional chemotherapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have also shown promise in relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphomas, including AITL. However, their use remains experimental due to concerns about potential T-cell depletion, which increases the risk of immunosuppression and infections.37

CAR T-cell therapy, while successful in B-cell malignancies, presents unique challenges in T-cell lymphomas. One major obstacle is “fratricide,” where CAR T cells attack each other due to shared T-cell antigens, leading to severe T-cell aplasia. Additionally, the risk of contamination by malignant T cells in CAR T-cell products can lead to poor treatment outcomes.38 This remains a significant limitation in the application of CAR T-cell therapy for T-cell lymphomas.

Mutations in TET2 and DNMT3A are pivotal in understanding the prognosis of T-cell lymphomas, particularly in AITL and other PTCL subtypes. These mutations are critical in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression, influencing DNA methylation and tumor progression. TET2 mutations, for example, have been associated with improved PFS due to altered DNA demethylation, which makes tumor cells more susceptible to therapeutic interventions.39

Future research is focused on optimizing treatment strategies for T-cell lymphomas, including refining patient selection criteria for ASCT and incorporating emerging therapies, such as targeted agents and immunotherapies. These advances hold significant promise for improving long-term survival and minimizing toxicity, marking a new era in the treatment of T-cell lymphomas.40

Optimizing Care for Patients With Relapsed or Refractory T-Cell Lymphoma: Current and Emerging Treatment Options

ASCT remains the only known curative option for patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphoma, but it is associated with significant toxicities, including lifelong immunosuppression and a high risk of infections. Unfortunately, patients who are older or frail, as well as those with contraindications, are often excluded from allogeneic transplantation. In such cases, treatment aims to either achieve remission or provide palliation. For this purpose, agents that induce a high remission rate with minimal toxicity are preferred, as recommended by the NCCN guidelines.41

Second-line agents, as outlined in the NCCN guidelines, are typically used in patients who are ineligible for transplantation or as a bridge to transplant for those who qualify. T-cell lymphoma presents several challenges, including its rarity and heterogeneity, contributing to limited interest from pharmaceutical companies and a lack of adequate tumor models for research.42 FDA-approved agents for relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphoma include pralatrexate, romidepsin, belinostat, brentuximab vedotin, and mogamulizumab.43 More aggressive regimens, such as ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide (ICE); etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHAP); bendamustine; and gemcitabine-based therapies, are also used, although they were originally designed for other lymphoma types.44,45 These regimens are sometimes used as a bridge to transplant in patients with high response rates.

At the time of Zain’s presentation, epigenetic therapies have shown promise, although no epigenetic agents have been approved as of 2023. For example, oral azacitidine demonstrated a 33% response rate in the phase 3 ORACLE trial (NCT03593018) for relapsed AITL, although it failed to meet its primary end point.46 Other ongoing studies include the combination of pembrolizumab and romidepsin, which has shown a 39.5% response rate, and the combination of romidepsin with azacitidine, which demonstrated a 73% response rate, particularly in patients with TFH subtypes.47,48 Romidepsin combined with azacitidine is a commonly used regimen, with positive results presented at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting 2022.49

Promising clinical trials include PRIMO (NCT03372057), a phase 2 study of duvelisib monotherapy, which showed an overall response rate of 50% and a median PFS of 6 to 9 months. This regimen is well tolerated and offers an alternative to chemotherapy for patients requiring palliative care or as a bridge to transplant.50 In cases where chemotherapy toxicity is a concern, especially in older patients, less toxic agents such as romidepsin or pralatrexate are preferred for palliation or as a bridge to transplantation.51 The combination of azacitidine and romidepsin had a 61% response rate, with higher responses observed in patients with TFH subtypes, and was well tolerated.52,53

Mutation analysis is critical in guiding treatment decisions when feasible. For example, epigenetic therapies such as romidepsin are preferred in TFH subtypes, while ALK inhibitors are recommended for ALCL-ALK-positive subtypes. In cases of ALCL-ALK negative, brentuximab vedotin can be used, particularly in patients who are not refractory.54 Overall, patients should be evaluated for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, as this remains the only curative option available. Studies from the City of Hope have shown that patients who have relapsed and are undergoing allogeneic transplants can achieve survival rates of 50% to 60%, offering a chance for long-term remission.55

CAR T-cell therapy for T-cell lymphomas presents unique challenges, such as fratricide, T-cell aplasia, and contamination. One solution under investigation involves targeting CD70 with CAR T cells, a novel approach currently being explored in clinical trials.56,57 Another strategy is using non-T-cell CAR therapies. While CAR T-cell therapy has been successful in B-cell malignancies such as relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, its application in T-cell lymphomas remains experimental due to the unique challenges posed by T-cell biology.58 In some cases, standard chemotherapy regimens continue to offer favorable outcomes, particularly in relapsed or refractory cases where novel agents are not available or accessible.59

Conclusions and Future Directions

PTCL remains a challenging diagnosis to manage, with current 5-year survival rates ranging from 30% to 40%, heavily influenced by the stage at diagnosis and specific subtype.58 This disheartening prognosis underscores the urgent need for improved treatment strategies. Ongoing research aims to tailor therapies to the distinct PTCL subtypes encountered in patients.59 This individualized approach is essential, as PTCL is a heterogeneous disease, and patients often respond differently to treatment. By focusing on subtype-specific interventions, we can significantly enhance treatment outcomes for patients.

Furthermore, this personalized approach is particularly crucial for patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL, who frequently face challenges in finding effective treatment options. Many of these patients are encouraged to participate in clinical trials, which offer access to innovative therapies aimed at addressing their unique disease characteristics.60 Although these treatments are still undergoing evaluation and have yet to receive regulatory approval, early evidence suggests promising responses among participants.61-63

In addition to pharmacologic therapies, stem cell transplantation and targeted therapies hold potential benefits for patients.64 However, the associated lifelong risks of stem cell transplants, which remain the only FDA-approved treatment for relapsed/refractory PTCL, often exclude many patients from this option.64 Thus, ongoing research into novel pharmaceuticals and combination therapies is vital to ensure that every patient has access to effective treatment options that optimize their prognosis.

Through continued research, progression of clinical trials, and the development of personalized treatment strategies, we aim to advance toward crucial cures and treatment modalities that enhance the 5-year survival rate for patients with PTCL across all subtypes. It is imperative that patients gain access to more effective treatment options to improve survival rates, highlighting the essential nature of ongoing research in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization was performed by JG, YL, and VC; methodology was developed by JG, YL, and VC; formal analysis was conducted by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; the investigation was carried out by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; resources were provided by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; data curation was managed by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; writing—original draft preparation was done by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; writing—review and editing was performed by JG, YL, and VC; visualization was executed by JG, YL, VC, JG, SK, KI, and CHP; supervision was provided by JG, YL, and VC; and project administration was handled by JG, YL, VC, and JG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors jointly agree to the accuracy of this work and are in favor of submitting it for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No patient data was directly utilized in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jasmine Zain for the opportunity to learn from a global leader in medicine. We are grateful to be part of MedNews Week. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Jill Gregory for her invaluable assistance in significantly improving the figures of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016,127(20):2375-2390. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569

- Pileri A, Pimpinelli N. The role of the immune system in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; an area requiring more investigation. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189(5):504-505, doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad255

- Stuver R, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Johnson WT, et al. Current treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2022;36(5):293-305. doi:10.46883/2022.25920960

- Neelapu, SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy – assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):47-62. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148

- Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Rivière I. The promise and potential pitfalls of chimeric antigen receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(2):215-223. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.009

- Khan M, Samaniego F, Hagemeister FB, Iyer SP. Emerging therapeutic landscape of peripheral T-cell lymphomas based on advances in biology: current status and future directions. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22):5627. doi:10.3390/cancers13225627

- Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):69. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00459

- MedNews Week Keynote Conference - Dr. Jasmine Zain (City of Hope) - T Cell Lymphoma Challenges. YouTube. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://tinyurl.com/3pbn4b2s

- Tigu AB, Bancos A. The role of epigenetic modifier mutations in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(11):8974-8988. doi:10.3390/cimb45110563

- Couronné L, Bastard C, Bernard OA. TET2 and DNMT3A mutations in human T-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(1):95-96. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1111708

- Caracciolo D, Mancuso A, Polerà N, et al. The emerging scenario of immunotherapy for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: advances, challenges and future perspectives. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12(1):5. doi:10.1186/s40164-022-00368-w

- Sibon D. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas: therapeutic approaches. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(9):2332. doi:10.3390/cancers14092332

- Foley NC, Mehta-Shah N. Management of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and the role of transplant. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24(11):1489-1499. doi:10.1007/s11912-022-01310-3

- Iżykowska K, Rassek K, Korsak D, Przybylski GK. Novel targeted therapies of T cell lymphomas. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):176. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-01006-w

- Harrop S, Abeyakoon C, Van Der Weyden C, Prince HM. Targeted approaches to T-cell lymphoma. J Pers Med. 2021;11(6):481. doi:10.3390/jpm11060481

- Albarrán V, San Román M, Pozas J, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy for solid tumors: current landscape and future challenges. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1352805. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1352805

- Targeted therapy to treat cancer. National Cancer Institute. Updated May 31, 2022. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/yeyj92th

- Chemotherapy to treat cancer. National Cancer Institute. Reviewed August 23, 2022. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/ykepb5j2.

- Immunotherapy. American Cancer Society. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/2jtwwzzs

- Stem cell transplants in cancer treatment. National Cancer Institute. Updated October 5, 2023. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://tinyurl.com/y8dhw8bn

- Fiore D, Cappelli LV, Broccoli A, Zinzani PL, Chan WC, Inghirami G. Peripheral T cell lymphomas: from the bench to the clinic. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(6):323-342. doi:10.1038/s41568-020-0247-0

- Huang YH, Qiu YR, Zhang QL, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic profiling of peripheral T cell lymphoma reveals distinct molecular and microenvironment subtypes. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(2):101416. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101416

- Luo L, Zhou X, Zhou L, et al. Current state of CAR-T therapy for T-cell malignancies. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207221143025. doi:10.1177/20406207221143025

- Hathuc V, Kreisel F. Genetic landscape of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Life (Basel). 2022;12(3):410. doi:10.3390/life12030410

- Ahmed N, Feldman AL. Targeting epigenetic regulators in the treatment of T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020;13(2):127-139. doi:10.1080/17474086.2020.1711732

- Zhang Y, Lee D, Brimer T, Hussaini M, Sokol L. Genomics of peripheral T-cell lymphoma and its implications for personalized medicine. Front Oncol. 2020;10:898. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00898

- Wang L, Yang L, Guan F, et al. TP53 and KMT2D mutations associated with worse prognosis in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Cancer Med. 2024;13(14):e70027. doi:10.1002/cam4.70027

- Heavican TB, Bouska A, Yu J, et al. Genetic drivers of oncogenic pathways in molecular subgroups of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133(15):1664-1676. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-09-872549

- Luan Y, Li X, Luan Y, et al. Therapeutic challenges in peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):2. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01904-w

- Shustov A, Cabrera ME, Civallero M, et al. ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: features and outcomes of 235 patients from the International T-Cell Project. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):640-648. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001581

- Yi JH, Kim SJ, Kim WS. Recent advances in understanding and managing T-cell lymphoma. F1000Res. 2017;6:2123. doi:10.12688/f1000research.12573.1

- Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D, International T-Cell Lymphoma Project. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4124-4130. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558

- d’Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, et al. Up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: NLG-T-01. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3093-3099. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719

- Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2190-2196. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0402

- Ratner L, Waldmann TA, Janakiram M, Brammer JE. Rapid progression of adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma after PD-1 inhibitor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1947-1948. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1803181

- Patel SG, May FP, Anderson JC, et al. Updates on age to start and stop colorectal cancer screening: recommendations from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):285-299. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.007

- Nguyen TB, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Asabe Y, et al. Identification of cell-type-specific mutations in nodal T-cell lymphomas. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(1):e516. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.122

- Ellin F, Landström J, Jerkeman M, Relander T. Real-world data on prognostic factors and treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Blood. 2014;124(10):1570-1577. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-573089

- Carty SA. Biological insights into the role of TET2 in T cell lymphomas. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1199108. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1199108

- Yap DRY, Lim JQ, Huang D, Ong CK, Chan JY. Emerging predictive biomarkers for novel therapeutics in peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1068662. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1068662

- Ong SY, Zain JM. Aggressive T-cell lymphomas: 2024: updates on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024;99(3):439-456. doi:10.1002/ajh.27165

- Weiss J, Reneau J, Wilcox RA. PTCL, NOS: an update on classification, risk-stratification, and treatment. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1101441. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1101441

- Escalon MP, Liu NS, Yang Y, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment of patients with T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2005;103(10);2091-2098. doi:10.1002/cncr.20999

- Skamene T, Crump M, Savage KJ, et al. Salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a subset analysis of the Canadian Cancer Trials Group LY.12 randomized phase 3 study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(10):2319-2327. doi:10.1080/10428194.2017.1312379

- Rosenthal AC, Munoz JL, Villasboas JC. Clinical advances in epigenetic therapies for lymphoma. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15(1):39. doi:10.1186/s13148-023-01452-6

- Ansell SM. Checkpoint blockade in lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(5):525-533. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.01522

- Alcantara M, Tesio M, June CH, Houot R. CAR T-cells for T-cell malignancies: challenges in distinguishing between therapeutic, normal, and neoplastic T-cells. Leukemia. 2018;32(11):2307-2315. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0285-8

- Mamez AC, Dupont A, Blaise D, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for peripheral T cell lymphomas: a retrospective study in 285 patients from the Société Francophone de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire (SFGM-TC). J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):56. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-00892-4

- Richardson NC, Kasamon YL, Chen H, et al. FDA approval summary: brentuximab vedotin in first-line treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist. 2019;24(5):e180-e187. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0098

- Zain, Jasmine, et al. (2022). Early results of CD70-directed CAR T-cell therapy in T-cell lymphomas. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts, 130(2), 123-130.

- Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al; JULIET Investigators.Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45-56. doi.10.1056/NEJMoa1804980

- Stuver R, Moskowitz AJ. Therapeutic advances in relapsed and refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):589. doi:10.3390/cancers15030589

- Afifi S, Mohamed S, Zhao J, Foss F. A drug safety evaluation of mogamulizumab for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(9):769-776. doi:10.1080/14740338.2019.1643837

- Wu CH, Wang L, Yang CY, et al. Targeting CD70 in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma using an antibody-drug conjugate in patient-derived xenograft models. Blood Adv. 2022;6(7):2290-2302. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005714

- Brammer JE, Zinzani PL, Zain J, et al. Duvelisib in patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma from the phase 2 PRIMO trial: results of an interim analysis. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):2456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-148939

- Liu Z, Lei W, Wang H, Liu X, Fu R. Challenges and strategies associated with CAR-T cell therapy in blood malignancies. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13(1):22. doi:10.1186/s40164-024-00490-x

- Takiar R, Karimi Y. Novel salvage therapy options for initial treatment of relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: so many options, how to choose? Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(14):3526. doi:10.3390/cancers14143526

- Peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment (PDQ)-health professional version. National Cancer Institute. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/2h78mr2y

- Moskowitz AJ, Stuver RN, Horwitz SM.Current and upcoming treatment approaches to common subtypes of PTCL (PTCL NOS; ALCL; and TFHs). Blood. 2024;144(18):1887-1897. doi:10.1182/blood.2023021789

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: relapsed/refractory. Lymphoma Research Foundation. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/4vn7mf6s

- Falchi L, Ma H, Klein,S, et al. Combined oral 5-azacytidine and romidepsin are highly effective in patients with PTCL: a multicenter phase 2 study. Blood. 2021;137(16):2161-2170. doi:10.1182/blood.2020009004

- Kalac M, Jain S, Tam CS, et al. Real-world experience of combined treatment with azacitidine and romidepsin in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma.Blood Adv. 2023;7(14):3760-3763. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009445

- Salhotra A, Yang D, Mokhtari S, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after salvage therapy with blinatumomab in patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia.Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(6):1084-1090. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.029

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). Cleveland Clinic. Reviewed June 27, 2023. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/2whh9eve

Highlighting Insights From the Marginal Zone Lymphoma Workshop

Clinicians outline the significance of the MZL Workshop, where a gathering of international experts in the field discussed updates in the disease state.