ECCO/ESMO study: Endocrine Rx for prostate cancer carries cardiovascular consequences

The first major study to address the cardiovascular adverse effects of endocrine therapy for prostate cancer could change attitudes toward treatment options because testosterone deprivation may have more impact on the patient’s life than it does on the androgen receptor.

The first major study to address the cardiovascular adverse effects of endocrine therapy for prostate cancer could change attitudes toward treatment options because testosterone deprivation may have more impact on the patient’s life than it does on the androgen receptor.

Mieke Van Hemelrijck and colleagues mined a database of 30,642 Swedish men for their research and presented the data at ECCO/ESMO 2009 in Berlin. This is the first, large study to address the cardiovascular adverse effects of endocrine treatment-orchiectomy, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, or anti-androgen (AA) monotherapy-in subgroups of prostate cancer patients, said Ms. Van Hemelrijck, a cancer epidemiologist and doctoral candidate in the division of cancer studies at King’s College in London.

“We saw an increased risk for the development of, and death from, each type of cardiovascular disease,” she reported. “While all forms of endocrine therapy were associated with risk, the least risk was seen with AA monotherapy. This may be because AAs do not block the production of testosterone but its access to the prostate, so some are still circulating and providing a cardioprotective effect.”

Subjects were drawn from the PCBaSe, which is based on the National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden, which started in 1996 and covers more than 96% of all incident prostate cancers compared to the Swedish Cancer Registry, which has an underreporting for prostate cancer of less than 3.7%.

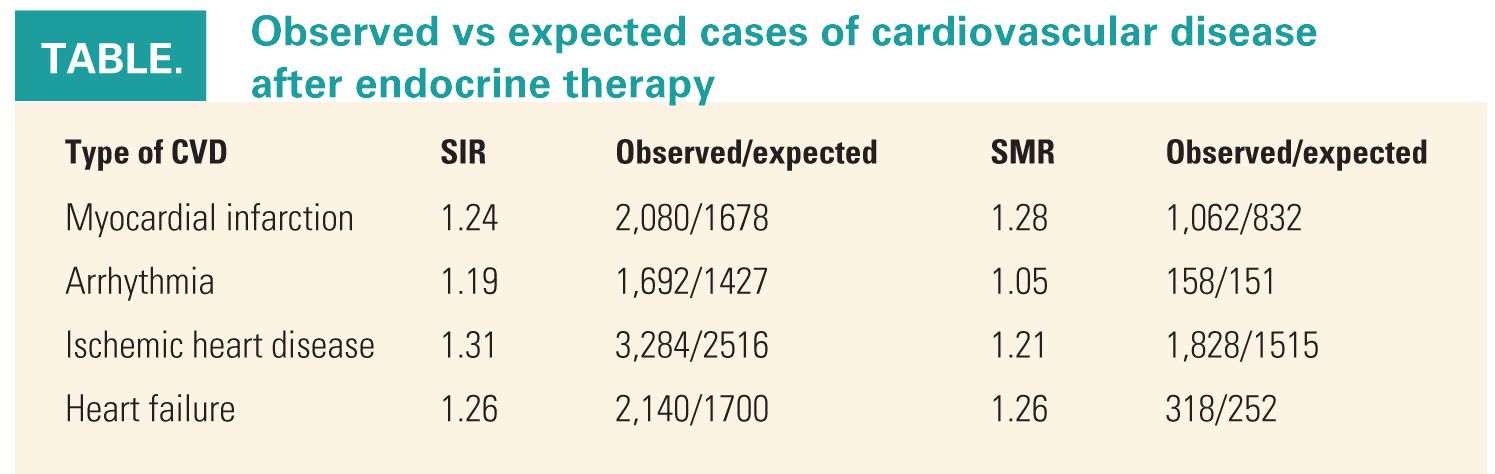

Investigators looked for concomitant diagnoses of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and arrhythmia. Standardized incidence and mortality ratios were calculated to compare observed and expected numbers of cardiovascular conditions (abstract 1BA).

Between 1997 and 2006, primary endocrine treatment was delivered to 30,642 prostate cancer patients, with 38% receiving short-term AA monotherapies plus GnRH agonists, 30% receiving GnRH agonists alone, 17% undergoing orchiectomy, and 11% receiving AA alone. For all cardiovascular diagnoses, incidence was increased in persons receiving endocrine treatment.

Cardiovascular disease risk was less pronounced for men who had heart disease at baseline (a standard incidence ratio [SIR] of 1.17) than for those who did not have heart disease at baseline (SIR of 1.41). “This could be due to ongoing treatment for this condition,” Ms. Van Hemelrijck suggested (see Table).

While the study did not show a causal effect, “we believe heart disease needs to be taken into account before starting prostate cancer patients on endocrine treatment, especially considering we are now using this approach not only for metastatic disease but for less advanced disease as well,” she said.

Commenting on the study, Fortunato Ciardiello, MD, co-scientific chair of ECCO/ESMO 2009, said that given the large patient population, the numbers are certainly clinically relevant and the potential relevant adverse effects are clearly stated.

“We need to take into account, in treating prostate cancer patients, especially with adjuvant treatment, that testosterone deprivation has more impact on the patient’s life than its direct effect on the androgen receptor,” said Dr. Ciardiello, who is a professor of medical oncology at the Second University of Naples in Italy. “In our choice of treatment, we should balance these factors. These findings could change our attitudes toward prostate cancer treatment.”

Whether one type of endocrine treatment may be less harmful than another is a question that has to be evaluated in a prospective trial, he added.