FDA Approval Alert: Epcoritamab in Relapsed/Refractory Follicular Lymphoma

The approval of epcoritamab may impact treatment options in the R/R follicular lymphoma space, according to Tycel Phillips, MD.

In June 2024, the FDA granted accelerated approval to epcoritamab-bysp (Epkinly) for patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma after 2 prior lines of therapy.1 The approval was based on results from the phase 1/2 EPCORE NHL-1 trial (NCT03625037),2 of which were recently presented at the 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting.

Prior to the approval, ONCOLOGY spoke with Tycel Phillips, MD, associate professor in the Division of Lymphoma and Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation at City of Hope in Duarte, California. Phillips spoke about the implications of approval and how this will impact treatment options in the space.

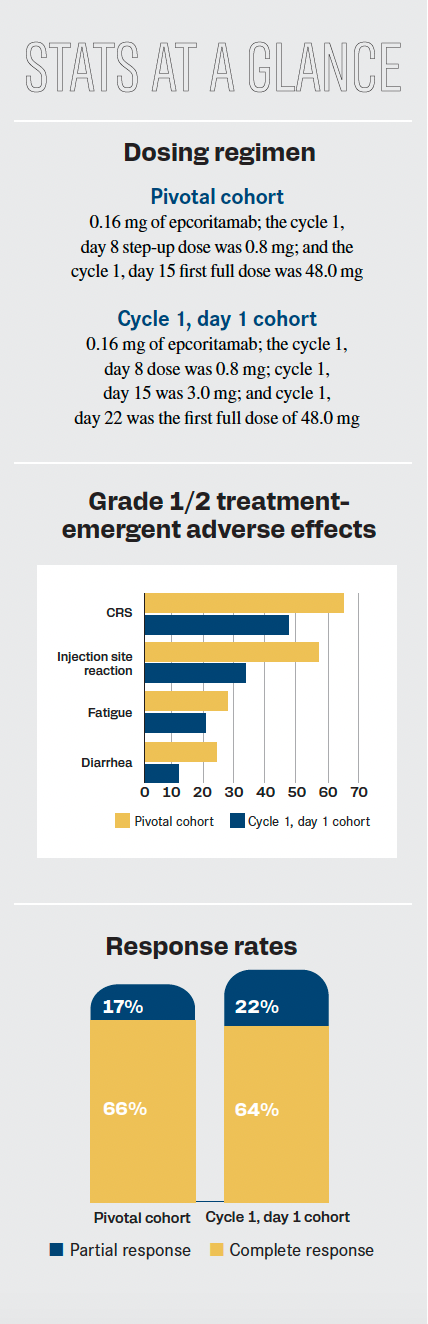

Stats at a glance of the EPCORE NHL-1 trial.

Topline results included an overall response rate of 82% (95% CI, 74.1%-88.2%) and a complete response rate of 60%. The median duration of response was not reached (NR; 95% CI, 13.7-NR). At 12 months, an ongoing response occurred in 68.4% of patients (95% CI, 57.6%-77.0%). Two different cohorts were assessed—the pivotal and cycle 1, day 1 cohorts—with investigators analyzing the impact these different dosing regimens had on patients.

Q / What does the approval of epcoritamab mean for this patient population?

Phillips / The biggest impact will be in centers that have picked 1 bispecific to keep on the formulary. Epcoritamab’s approval in large cell lymphoma has allowed them to keep 1 bispecific agent or formulary and doesn’t require them to have [multiple agents stocked].3 In this situation, if they have a bispecific for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL] and an antibody specific for follicular lymphoma, it will require [the clinic] to have either epcoritamab, glofitamab-gxbm [Columvi], or mosunetuzumab-axgb [Lunsumio] for follicular lymphoma.

This potentially allows for ease of use in that situation. There are fewer difficulties with staff [and] infusion nurses, [as well as not having to deal] with different bispecifics and being more comfortable with dealing with 1 drug. In the long term, it is always better for the patients because it’s easier to manage the toxicity that may come from this. There is [also] more familiarity with the step-up of dosing for epcoritamab, which is different from what we have with mosunetuzumab and glofitamab.

Some of the [adverse] effects that come from it, like cytokine release syndrome [CRS] and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome [ICANS], can be associated with this.

Q / How promising are the data from the EPCORE NHL-1 trial?

Phillips / The data are still a bit immature compared with what we see with CAR [chimeric antigen receptor] T drugs and even mosunetuzumab. The duration of response is still to be determined, as I’m sure [those] data [are] still maturing…. The overall response and complete response rates look very similar to what we see with mosunetuzumab. In that aspect, there are no major differences between the 2 drugs. The CRS events appear to be a little less than what we saw in large cell lymphoma but not drastically different.

The big takeaway [is the efficacy]. It’s still to be determined how effective and durable this will be. Given that epcoritamab appears to be a more effective drug in large cell lymphoma than mosunetuzumab, I would hope that would translate into longer responses in follicular lymphoma, especially given some of the other aspects of the drug, which is treatment to progression. This is a little different from mosunetuzumab, and the CRS rates seem to be a bit higher in criteria than what we saw with mosunetuzumab. To justify that, you would want to hope for a longer duration of response with this drug.

Q / Are there any unmet needs that epcoritamab would help to reduce?

Phillips / As we try to transition these bispecifics into the community setting, having these drugs available allows patients [the opportunity] who can’t [receive] CAR T-cell therapy or can’t get to other academic centers for clinical trials. This provides them with a more effective option, especially with the loss of the PI3K inhibitors in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. When chemotherapy or lenalidomide [Revlimid] fails these patients, there’s a bit of a void there as far as agents that could provide some durability of response. Having this fills that void, [as well as] being able to be off the shelf and readily available for patients who live in situations where they can’t get access to CAR T-cell therapy or get to a major academic center. These drugs could bridge that gap and give these patients adequate response durability. And after dealing with step-up dosing and safety, these drugs are quite promising, especially compared with the now-defunct Δ inhibitors of chemotherapy. Some of these other drugs may be coming down the line.

Q / How would you implement this treatment into your clinical practice?

Phillips / This is an effective therapy that we can use in a third-line setting, or even in patients who may have progression of disease after 24 months [of treatment. Patients with] early progression tend to have poor outcomes, especially when given more cytotoxic agents like chemotherapy. Ideally, this treatment does not appear to be impacted by that prognostic factor. It does allow utilization in that situation. If patients are to get lenalidomide or rituximab [Rituxan] in the frontline setting, this allows the use of this drug after that…. There’s just 1 real agent—tazemetostat [Tazverik]4—that has the current approval [in the third-line setting as of right now. Epcoritamab] allows for a more effective therapy and a more durable response than what we see with tazemetostat.

Q / Are there any significant toxicities that stand out to you?

Phillips / Besides the CRS, it’s the ICANS. That’s one thing we always keep an eye on. The rates of those are much less with the bispecifics than we will see with CAR T-cell therapy. Infections are [another] thing we will have to keep an eye on because of how bispecifics work; so you’re more prone to viral infections. The good news is that after the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve come a long way, and those infections can be managed and treated. We’re not having nearly as many fatalities as we have in the early parts of the pandemic. We’re keeping an eye on the patient’s immunoglobulin levels and repeating those, if necessary, to prevent more recurrent viral infections, which is important.

Anytime we constantly keep patients on treatment, we run the risk of other things that may come up [later down the line] that we may not anticipate. At least in the short term, infection, ICANS, and CRS are the biggest things to be concerned about with this type of treatment. This is a little different from what we see with chemotherapy, where you get the nausea, vomiting, bacterial infections, and the secondary malignancies that come along with it.

"The bispecifics have a lot of potential for upward mobility, so readily anticipate that these will be explored in the frontline setting," said Tycel Phillips, MD.

Q / Are there any other plans to further research epcoritamab in this patient population or perhaps those with other types of cancer?

Phillips / The bispecifics have a lot of potential for upward mobility, so readily anticipate that these will be explored in the frontline setting. Epcoritamab and the other bispecifics have already been explored in the second-line setting in combination with lenalidomide. I’m sure that combination as a single agent—and probably lenalidomide—will be explored in untreated or newly diagnosed patients.

We’re sort of seeing the same phenomenon in [DLBCL], which is the most common lymphoma. Epcoritamab and glofitamab have been studied in the frontline setting in that patient population, and epcoritamab has been studied in mantle cell lymphoma. There’s also a study looking at this drug in Richter transformation, [which comprises patients with] chronic lymphocytic leukemia who develops a large cell lymphoma transformation. There are multiple non-

Hodgkin lymphoma subsets that have been explored with epcoritamab and the bispecifics in general because of their combined ability with other agents. I would anticipate we’ll likely see them combined with other drugs with earlier lines of therapy than what the current FDA approvals will say at this current time.

References

- FDA grants accelerated approval to epcoritamab-bysp for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. FDA. June 26, 2024. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/26s9myey

- Vose J, Vitolo U, Lugtenburg P, et al. EPCORE NHL‑1 follicular lymphoma (FL) cycle (C) 1 optimization (OPT) cohort: expanding the clinical utility of epcoritamab in relapsed or refractory (R/R) FL. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(suppl 16):7015. doi:10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.7015

- FDA grants accelerated approval to epcoritamab-bysp for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphoma. FDA. May 19, 2023. Accessed July 8, 2024. https://shorturl.at/HIsMi

- FDA granted accelerated approval to tazemetostat for follicular lymphoma. FDA. June 18, 2020. Accessed July 8, 2024. https://shorturl.at/2MAVf

Highlighting Insights From the Marginal Zone Lymphoma Workshop

Clinicians outline the significance of the MZL Workshop, where a gathering of international experts in the field discussed updates in the disease state.