International cancer diagnosis, treatment varies widely

Coverage in most countries is universal, but limited resources can sometimes hinder how much coverage a person can expect.

ABSTRACT: Coverage in most countries is universal, but limited resources can sometimes hinder how much coverage a person can expect.

During the heated debate over healthcare reform, advocates and adversaries of the issue often pointed to other countries as examples of the right-or wrong-way to manage healthcare.

On the plus side, healthcare coverage in most countries is universal, though limited resources can sometimes hinder how much coverage a person can expect. And just like the United States, foreign healthcare systems are looking to rein in costs.

Although foreign public health systems are frequently praised for providing all-encompassing care, they actually consist more of a mix of public and private health insurance, explained a panel of experts at the 2010 Association of Community Cancer Centers meeting in Baltimore.

In Canada, for example, the provinces primarily fund healthcare with the federal government contributing 15%, said Carol Sawka, MD, FRCPC, vice president for clinical programs and quality initiatives for Cancer Care Ontario.

But there are limits to what a public healthcare system can afford, she added. Coverage includes intravenous systemic treatment but many Canadians also carry private insurance, which is widely used to pay for some cancer treatments, like oral chemotherapy, she said.

In fact, most foreign healthcare models follow that same structure: Government-funded schemes supported by private provisions, said Harris W. Dalrymple, PhD, director of project management for Pharmaceutical Product Development, a contract research organization. In Western Europe, except for France, most countries have financial limitations around oncology resources. "As you go further East, there are generally fewer treatment centers relative to the size of the population, and most countries have an established per capita allowance for care. And once that's spent, it's over," he said.

From left, Harris W. Dalrymple, PhD, Anne-Pierre Pickaert, Carol Sawka, MD, FRCPC, and panel moderator Cliff Goodman, PhD, discussed healthcare access in foreign countries at the 2010 ACCC meeting. Image courtesy of ACCC.

In the UK, no one is ever denied access to healthcare, but the system presents two major hurdles to cancer care: Long wait times for treatment and an arduous approval process for new drugs.

"In the UK, wealthy patients who are diagnosed with cancer and denied access to innovative and expensive drugs go abroad to get treated," said Anne-Pierre Pickaert, a consultant in oncology market access with Kantar Health. "There are 20,000 premature deaths from rare cancers each year because it's almost impossible to get drugs approved for them." In addition, diagnosis and referral can be very time-consuming and unwieldy in the National Health Service (NHS).

Wait times in Canada also can be lengthy. "There is no oversupply of oncologists [in Canada], and sometimes patients have to wait a long time to get treated, but there is a national focus on improving wait times and we have seen good results in some areas," Dr. Sawka said.

In a universal care scenario, there is also less incentive to provide more treatment. "Hospitals do not have a stake in encouraging overutilization of imaging," Dr. Sawka said. "On the oncology side, medical oncologists do not buy and sell drugs, which means they do not have a financial stake in the drugs they order or how long they give them."

Drug access

Ms. Pickaert described France's early access program for cancer drugs whereby patients can continue to receive an investigational drug, before it is approved, if they have benefited from the drug as part of a clinical trial. This is similar to the FDA's compassionate use policy. This kind of early access is expensive and "most of the time, French oncologists have no idea how much cancer drugs cost," she said. Early access programs in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK are similar to, but not as comprehensive as, the one in France.

In the UK, there is a risk-sharing program for recently approved drugs, Dr. Dalrymple said. Payment for a drug will be made to the manufacturer if the drug proves efficacious in individual patients. If the drug is not seen to convey a benefit, the manufacturer will have to absorb the cost of that initial treatment period.

In the U.S., FDA drug advisory committees are prohibited from discussing the price of a drug. But in Canada, cost effectiveness is a major part of the drug approval process. "It's usually the most contentious [part]. Canadian drugs have to provide good value as well as be effective," Dr. Sawka said.

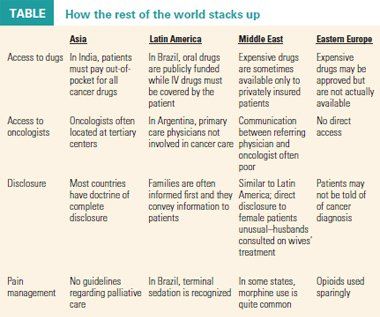

Source: "The treatment of cancer in foreign healthcare systems," Harris W. Dalrymple, PhD, 2010 ACCC

Patients first

Two of the panelists agreed that healthcare in the U.S. is the most patient-oriented. But progress is taking place in other regions. The UK now has more patient-centered advocacy groups and support groups than the rest of Europe. And patients are spared an onslaught of potentially confusing drug-related hype, as direct-to-consumer marketing is not allowed.

Pain management is another area where changes are under way. In Italy, for instance, the use of opioids for pain management was not legalized until 2001, and even then restrictions were tight. Rules regarding opioid use were relaxed in 2007, Dr. Dalrymple said.

In Canada, "we're getting better at integrating palliative care into treatment as a whole," Dr. Sawka said.

In response to a question from the audience about the malpractice milieu, the panelists seemed nonplussed. Dr. Sawka said that Canadian patients are "less likely to initiate malpractice lawsuits than those in the U.S." In France, such suits are very much uncommon, at least in the oncology field.

"General practitioners and specialists have stopped undertaking certain procedures they used to do in the past for fear of increasing malpractice lawsuits. However, oncology remains a fairly protected area. Some French patients might be angry at their oncologists, but the idea of suing their oncologists does not come to their minds as easily as it would to U.S. patients," Ms. Pickaert said.