Recap: A Review of Multiple Myeloma Trials That Impact the Standard of Care

A panel of experts provides a discussion on treatments for newly diagnosed transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible relapsed multiple myeloma, and how recent clinical trial data presented at ASH 2021 can be applied to clinical practice.

At an Around the Practice program hosted by CancerNetwork®, experts spoke about updates in the treatment of multiple myeloma that were presented at the 2021 American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting. The panel was led by Rafael Fonseca, MD, director for Innovation and Transformational Relationships at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Arizona.

Other experts on the panel included Caitlin Costello, MD, associate professor of medicine at University of California San Diego Health; Jeffrey V. Matous, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Health Science Center in Denver; Robert Z. Orlowski, MD, PhD, chairman, ad interim director of Myeloma, professor of medicine in the Departments of Lymphoma/Myeloma and Experimental Therapeutics at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; and Krina K. Patel, MD, MSc, associate professor in the Department of Lymphoma/Myeloma, Division of Cancer Medicine at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Regimens for Transplant-Eligible Myeloma With Data Updates at ASH 2021

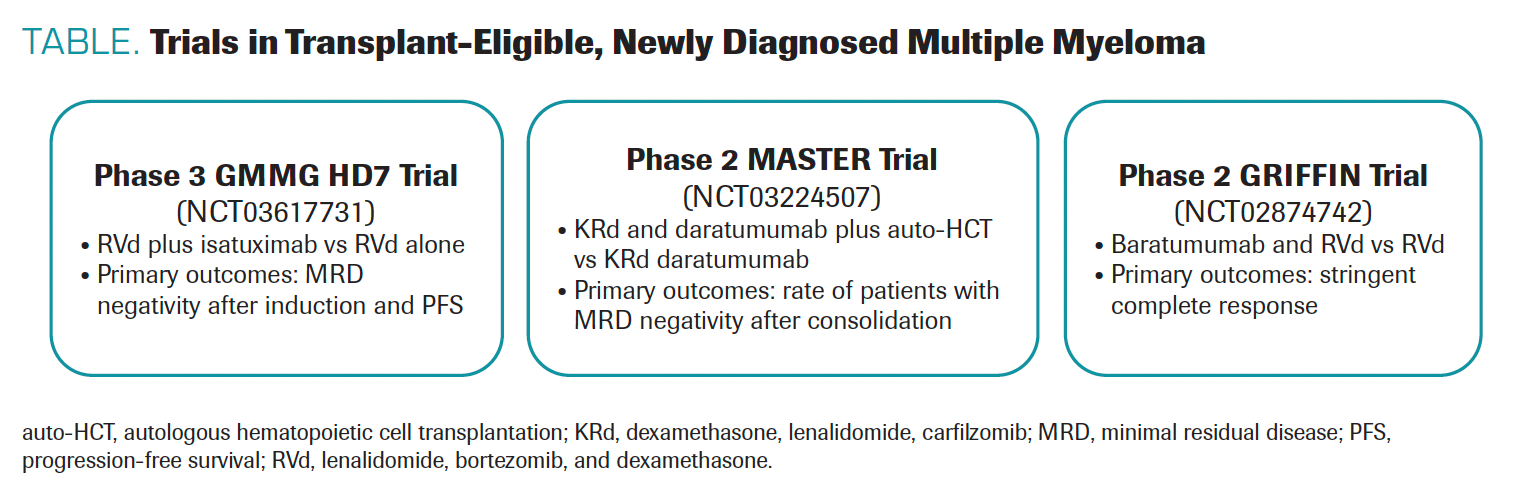

Fonseca: We saw at the ASH [American Society of Hematology] meeting an update on the 2-year follow-up regarding the GRIFFIN study (NCT02874742).1 What is your take on that, and what are the clinical implications of this study?

Costello:I’ve said before that daratumumab [Darzalex] is the gift that keeps on giving, because [studies] keeps showing the importance of including this drug in every step of our treatment regimens. The GRIFFIN study that was updated at ASH included 24 months of maintenance for these patients and showed what we were expecting. That is that the addition of daratumumab to the triplet of RVd [lenalidomide (Revlimid), bortezomib (Velcade), and dexamethasone], both done in induction and followed by consolidation, followed by randomized daratumumab-lenalidomide vs lenalidomide maintenance, showed a continued deepening of response after consolidation through maintenance.1

We’re seeing patients who got the quadruplet followed by daratumumab-lenalidomide maintenance are achieving CR [complete response] rates that seem unprecedented [equating to] 80% or greater CR rates with MRD [minimal residual disease] rates that are significant, from the consolidation phase through those 24 months of maintenance. There was almost a tripling of MRD negativity at [the 10-6 threshold]. We’re seeing that there are such deep responses with daratumumab, in induction, consolidation, maintenance. Now, it’s important to say that this study wasn’t powered for progression-free survival [PFS], but very clearly you can start to see a trend in those patients who received daratumumab. Both arms were somewhere over 80% rate in terms of PFS, and neither of them had reached a median after just a little over 3 years with no new safety concerns. This is proving to us that a quadruplet regimen at induction with maintenance and daratumumab is probably going to be here to stay. I’ve started to incorporate this routinely across the board for my newly diagnosed patients.

Fonseca: We saw an update on the MASTER trial (NCT03224507). What did we learn from MASTER that was presented at the ASH meeting?

Patel: What I like about [the MASTER] trial is the end point [of MRD negativity at completion of consolidation].2 We were taking this prognostic tool we have in myeloma to [figure out if] we stop therapy. [This combination involved daratumumab, carfilzomib (Kyprolis), lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd)]. Instead of using bortezomib like the GRIFFIN trial, it’s carfilzomib; then they’re using 4 cycles of induction, transplant, and then consolidation based on patient’s MRD status. They used 0, 4, and 8 cycles of consolidation, but if patients were MRD negative with 10-5 at least twice, they got to stop all therapy and go on observation, which I think is a big feat for patients. It was a great study where we saw amazing MRD negativity. It was 80% of patients overall who reached MRD negativity, which is the deepest response we’ve seen in upfront trials—more so than GRIFFIN—when it comes to MRD. Then 66% [of patients] were MRD at 10-6, and the CR rate was 86%. PFS rate was still 87% at 2 years, so these patients have done well.

The flip side, though, is that they showed the MRD resurgence. They’re watching MRD at 6 months after they stopped treatment and then every year and kept an eye on what happened to those patients who stop. Especially in the high-risk patients—the ultra-high-risk patients, those who had 2 high-risk features—27% of them ended up having MRD positivity or they had relapsed at 12 months. For standard-risk patients, this looks great. For high-risk patients, stopping therapy is something that we have to keep a closer eye on.

Fonseca: Let’s briefly discuss the GMMG HD7 (NCT03617731) study and what it tells us.

Matous: [The GMMG-HD7 trial is] like GRIFFIN, but with isatuximab [Sarclisa] instead of daratumumab, so a different anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.3 In just under 2 years, they enrolled 660 patients in 67 centers around the country on this trial, which was for transplant eligible patients. The induction was isatuximab–RVd versus RVd; again, quadruplet vs a triplet. The primary end point of the study was MRD negativity by flow cytometry to 10-5.

The trial was reported relatively early, just after the induction phase. The intent of this study is to take patients to transplant and then post-transplant care. In the induction phase, the CR rates between the 2 groups of patients were very similar—in the order of 20% to 25%—but the MRD negativity rates strongly favored the quadruplet over the triplet, about 50% vs about 36%. What’s always good to see in these trials is that there’s no additional safety signal that has emerged at least over the induction phase of the trial.

Fonseca: How do you decide which patients should quadruplet therapy and are there any situations where you could argue for a triplet drug combination?

Orlowski: In terms of quadruplet [with] a CD38 antibody, a proteasome inhibitor, an IMiD [immunomodulatory drug], and a steroid, I’ve moved over to using quadruplets for every patient with high-risk disease in the newly diagnosed setting because we know that they have more difficult disease. Although it responds well, it tends to relapse more quickly, and the deeper responses, the greater MRD negativity is what we need to achieve. I also tend to do this for people with a high degree of disease burden. Same rationale [applies] there; If you’ve got 10% plasma cells at baseline, it’s easier to get you into a complete remission and MRD negativity than if [you present with a level of] 75%. Where the question comes in is where you draw the line between high disease burden and lower disease burden; I say 50% plasma cells or more. In the future, we will probably be giving 4 drugs for virtually everybody unless there will be a compelling reason why 1 of those 4 drugs is contraindicated in a patient.

Fonseca: Does it even make sense or is there a future where risk stratification will become slightly less important?

Orlowski: Certainly, there is a possibility that we’ll be doing 4 drugs even for patients with standard risk and low disease burden at the time of diagnosis. That’s what we’d all like to see is use of early measure of response where we could do a response-adapted therapy. Clearly, there are people that are already going to achieve CR and MRD negativity just with a triplet. If you get to MRD negativity, it’s not clear that the addition of another agent is of benefit. Ideally, it would be nice to have that assay at the beginning to work with.

Matous: I can tell you that patients who are referred to us for transplant are primarily getting RVd. Some of the practitioners have adopted a quadruplet, daratumumab–RVd in this case, and there are a few FORTE trial [NCT02203643] believers out there that are giving KRd induction following the FORTE trial.4 We’re seeing both triplets and quadruplets out there. I think [clinicians] are getting much more comfortable with quadruplet regimens. [Physicians] in the practice setting were late to adopt daratumumab initially when it was FDA approved, and then anytime you’re incorporating something new into your standard, there’s always a little bit of discomfort.5 I do see more of the community adopting the daratumumab into the induction regimen than we saw for a year ago.

Fonseca: CASSIOPEIA [NCT02541383] has showed from early data that if you don’t get daratumumab, you don’t do as well. Do you think that should be a reason for the use of daratumumab routinely if a patient only got RVd induction?

Costello: This is the question that we’re all waiting to answer, and much of it will be answered soon. We have quite a few different studies that are ongoing looking at daratumumab in the maintenance setting, such as AURIGA [NCT03901963] which is taking all patients who are daratumumab naïve and [treating them with either] daratumumab/lenalidomide vs lenalidomide maintenance. Studies like that will start to help us answer the question about the role [of maintenance] in daratumumab-naïve patients. For patients who have not had daratumumab upfront, undergo their transplant, still have residual disease, and are MRD positive, there’s certainly an argument to try and push a little bit harder in the post-transplant setting. It is not a routine thing that I would recommend for all patients across the board. It’s getting harder and harder to not use as early in the process as possible.

ASH 2021 Updates in Transplant-Ineligible Myeloma

Fonseca: What are the factors that you’re taking into consideration as you face treatment selection for these patients?

Patel: As a former [transplant physician], I would say everybody was eligible for transplant. If [a patient is] truly transplant ineligible, they [must have] organ failure or they’re not going to be able to do well with transplant. Usually, those are my frail patients. Then I tailor my therapy according to [their] toxicity. In Texas, we have many patients who have metabolic syndrome or neuropathy, so I’m also monitoring my dosing of bortezomib, for instance. I tend to use triplets and usually it’s either VRd-lite vs the MAIA trial [NCT02252172] regimen of daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone [DRd].6 Depending on what that patient really [experiences], if they have horrible asthma and [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], I might go with the VRd-lite. I tend to do more DRd now just because once a month injection is a lot easier for patients to take. It depends on their comorbidities and their performance status.

Fonseca: Can we discuss the MAIA trial?

Matous: The MAIA trial is one of those trials that truly are practice-changing, and it changes the standard of care for our patients that we deem to be transplant ineligible. MAIA was a trial that accrued and randomized over

700 patients between Rd—which we know from previous studies is a very good option for older, frail patients—and Rd plus daratumumab (Table). The daratumumab [treatment] was given until disease progression in that arm. This is a more real-world trial, in my opinion, than some of the other studies that have been done in transplant-ineligible patients. For example, SWOG 0777 [NCT00644228] was a transplant-ineligible study, but the patients were younger on that trial [than the average population].

TABLE. Trials in Transplant-Eligible, Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma

In this trial, the median age was 73 and most of the patients were between 75 and 90 years of age. What we learned in this trial is that with longer follow-up presented at EHA [European Hematologic Society Congress] last year was that there was an overall survival benefit to the triplet compared with the doublet, even with nearly 50% crossover between the doublet arm and the daratumumab later. That in my mind is impressive. DRd has become my go-to off-trial [regimen] for transplant-ineligible patients. Another reason [for that] in my mind is to avoid peripheral neuropathy. It’s really challenging to avoid peripheral neuropathy in older patients, and when we treat anybody, we want long survival and excellent quality of life. The MAIA trial demonstrated that DRd is an excellent way to achieve that for this population of patients.

Fonseca: What are the implications for clinical practice based on what has been published and recently reported at the ASH meeting regarding MAIA?

Costello: In MAIA, we finally got that 5-year follow-up that did show clinically meaningful overall survival improvement and about a 30% or more reduction in the risk of death. The combination of DRd for our transplant-ineligible patients does offer a dramatic, clinically significant change to our practice. Historically, we’ve put patients who are transplant ineligible on doublets, RVd-lite, or RVd and crossed our fingers and hoped the neuropathy wasn’t too bad. Most patients are eligible for this. There are very few patients for whom I hesitate to give this to. It does allow for longer treatment. You don’t have to stop the bortezomib after a certain period of time with DRd. Patients do well with it. In the midst of a pandemic, it’s practical to realize that the addition of daratumumab may provide a bit more immunosuppression or immunocompromise patients more at [risk for] COVID-19. That has been something that we’ve had to reckon with in the past couple of years. DRd is probably the new standard of care for transplant ineligible [patients], particularly in the older

population.

Fonseca: Do you do dose adjustments in your practice with the medications, or do you start everyone at the standard doses?

Costello: We want to put our best foot forward as much as we can to get an early and a deep response. The patients who are on DRd per MAIA are going to be on [lenalidomide] for the long run, and that is challenging. You can have significant fatigue, concentration concerns, and diarrhea, all which can affect quality of life. I try to start them at a full dose and will dose reduce accordingly depending on how they’re tolerating it for the long run. My goal is to keep them on it. I want to make those adjustments to make

that happen.

Fonseca: What constitutes an adequate and successful response in patients who are transplant ineligible?

Orlowski: Adequate and successful could be 2 different definitions. As for the transplant-eligible patients, the greater the cytoreduction, the better it will be in for long-term outcomes. Trying to get into CR and MRD negativity is a valuable goal. We balance that against the potential increased toxicity for these patients, and we try to make sure that we’re maintaining and hopefully even improving their quality of life and that their functional status is able to be maintained as well. There’s a greater focus on those clinical aspects rather than on just the level of M protein or the [serum] free light chains.

Fonseca: Has your practice completely changed to subcutaneous daratumumab. Is there any reason to keep using the intravenous administration route?

Orlowski: The subcutaneous [formulation] is better tolerated. There are fewer reactions to it. The time in the chair is decreased, and there’s even a suggestion that the response is better. Part of that is because the 1800-mg flat dose, which is given as the subcutaneous injection, is often a larger dose than the 16 mg/kg that we use intravenously. It may just be that more drug is better. I don’t know of any patient that I have who I still receive intravenous daratumumab.

Fonseca: Do we bring MRD testing into this population? What about blood-based methods for MRD determination?

Costello: When we’re talking about a transplant-ineligible population and, for the most part, we’re talking about an older population. Realistically then we’re talking about quantity of life [as a treatment goal]. If we are trying to provide people with the best quality of life, sometimes that means we have to make some compromises. I love to see the MRD data, but I think it’s not necessarily a practical approach for all older or transplant-ineligible patients to be able to push very hard to get to that MRD state. I have not incorporated it into my practice for the majority of my older and definitely not my frailer patients because I wouldn’t change my practice according to it.

Fonseca: I think it’s fair to say we push more for MRD in transplant-eligible patients, not to say that it’s proven to be the right way to go, but that’s what we’re doing right now. We’re very happy when we get into an MRD-negative status when a patient gets treated like this.

References

- Laubach JP, Kaufman JL, Sborov DW, et al. Daratumumab (DARA) plus lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVd) in patients (pts) with transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ndmm): updated analysis of GRIFFIN after 24 months of maintenance. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):79. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-149024

- Costa LJ, Chhabra S, Medvedova E, et al. Daratumumab, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone with minimal residual disease response-adapted therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. Published online December 13, 2021. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01935

- Goldschmidt H, Mai EK, Nievergall E, et al. Addition of isatuximab to lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone as induction therapy for newly-diagnosed, transplant-eligible multiple myeloma patients: the phase III GMMG-HD7 trial. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):463. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-145097

- Gay F, Musto P, Rota-Scalabrini D, et al. Carfilzomib with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone or lenalidomide and dexamethasone plus autologous transplantation or carfilzomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone, followed by maintenance with carfilzomib plus lenalidomide or lenalidomide alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (FORTE): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1705-1720. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00535-0

- FDA approves daratumumab for transplant-eligible multiple myeloma. News release. FDA. September 26, 2019. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://bit.ly/3J8hRyp

- Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(11):1582-1596. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00466-6

EP: 1.Triplet and Quadruplet Induction Regimens for Transplant-Eligible NDMM: Focus on GRIFFIN and MASTER Trials

EP: 2.Choosing Between Triplet and Quadruplet Induction Regimens for Transplant-Eligible NDMM

EP: 3.Treatment Duration and Response to Induction Therapy in Transplant-Eligible NDMM

EP: 4.First-Line Treatment Options for Transplant-Ineligible NDMM: Focus on MAIA Trial

EP: 5.Outcomes with Daratumumab in Frontline Versus Subsequent Lines of Therapy in Transplant-Ineligible MM

EP: 6.Novel BCMA-Targeting Agents for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

EP: 7.BCMA-Targeting Bispecific Agents for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Treatment

EP: 8.CAR-T Therapies in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: CARTITUDE-1 and KarMMA Studies

EP: 9.Novel Agents Under Investigation for Multiple Myeloma

EP: 10.Unmet Needs and Future Perspectives in Multiple Myeloma Treatment

EP: 11.Recap: A Review of Multiple Myeloma Trials That Impact the Standard of Care

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.