Tandem Transplantation in Multiple Myeloma

The use of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cellsupport in the past decade has changed the outlook for patients withmultiple myeloma. In newly diagnosed patients, complete remissionrates of 25% to 50% can be achieved, with median disease-free andoverall survivals exceeding 3 and 5 years, respectively. Despite theseresults, autologous transplantation has not changed the ultimatelyfatal outcome of the disease, as there is no substantial evidence of“cure” in most published studies. An additional high-dose chemotherapycourse (with tandem transplants) appears to improve progressionfreesurvival, although the effect is not discernible until 3 to 5 yearsposttransplant. The recent reports of tandem autologous transplant formaximum cytoreduction followed by nonmyeloablative allogeneictransplant for eradication of minimal residual disease appears promisingand deserve further investigation. A central issue of tandemtransplants, whether they involve autologous or allogeneic transplants,revolves around defining the subsets of patients who will benefitfrom the procedure. Good-risk patients (defined by normal cytogeneticsand low beta-2–microglobulin levels), especially those who achievea complete or near-complete response after the first transplant, appearto benefit the most from a second cycle. High-risk patients (defined bychromosomal abnormalities usually involving chromosomes 11 and 13and high beta-2–microglobulin levels) whose median survival aftertandem transplant is less than 2 years should be offered novel therapeuticinterventions such as tandem “auto/allo” transplants. Until theefficacy and safety of this procedure is fully established, it should belimited to high-risk patients.

ABSTRACT: The use of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell support in the past decade has changed the outlook for patients with multiple myeloma. In newly diagnosed patients, complete remission rates of 25% to 50% can be achieved, with median disease-free and overall survivals exceeding 3 and 5 years, respectively. Despite these results, autologous transplantation has not changed the ultimately fatal outcome of the disease, as there is no substantial evidence of "cure" in most published studies. An additional high-dose chemotherapy course (with tandem transplants) appears to improve progressionfree survival, although the effect is not discernible until 3 to 5 years posttransplant. The recent reports of tandem autologous transplant for maximum cytoreduction followed by nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplant for eradication of minimal residual disease appears promising and deserve further investigation. A central issue of tandem transplants, whether they involve autologous or allogeneic transplants, revolves around defining the subsets of patients who will benefit from the procedure. Good-risk patients (defined by normal cytogenetics and low beta-2-microglobulin levels), especially those who achieve a complete or near-complete response after the first transplant, appear to benefit the most from a second cycle. High-risk patients (defined by chromosomal abnormalities usually involving chromosomes 11 and 13 and high beta-2-microglobulin levels) whose median survival after tandem transplant is less than 2 years should be offered novel therapeutic interventions such as tandem "auto/allo" transplants. Until the efficacy and safety of this procedure is fully established, it should be limited to high-risk patients.

Newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation have a superior outcome in terms of eventfree and overall survival, compared with conventional chemotherapy recipients.[ 1-3] Although this has been proven in only one randomized trial, the results of several phase II studies provide a substantial body of evidence favoring the use of high-dose therapy (recently reviewed by Fassas and Tricot).[4] Despite this improvement in survival, it is clear that autologous stem cell transplant (auto- SCT) is not curative in the majority of patients. Allogeneic transplant (allo-SCT) is the only accepted curative therapy for multiple myeloma, given documented molecular remissions that are attributed to the graft-vs-myeloma effect, which appears to overcome chemotherapy resistance.

One approach to improving outcome in multiple myeloma patients is to administer additional cycles of high-dose therapy (usually two to three) with "tandem" transplants. Traditionally, autologous stem cells-and, more recently, allografts following administration of a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen-have supported the second cycle. This review will focus on the prognostic factors that predict longterm event-free and overall survival following tandem auto-SCT and the potential for cure and benefit associated with tandem "auto/allo" transplantation.

Historical Background

High-dose therapy for multiple myeloma was introduced by the Royal Marsden Group.[5] These investigators reported an impressive 100% overall response rate in nine relapsed multiple myeloma patients following high doses of melphalan (Alkeran), 100 to 140 mg/m2, without stem cell support. Subsequently, several trials demonstrated high-dose therapy to be superior to conventional chemotherapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients with response rates of 70% to 90%, complete remission (CR) rates of 25% to 50%, and median overall survivals of 4 to 5 years.

TABLE 1

Results of Studies of Multiple Cycles of High-Dose Chemotherapy in Multiple Myeloma

The Intergroupe Franais du Mylome was the first to randomize 200 previously untreated multiple myeloma patients to high-dose therapy with auto-SCT support (melphalan, 140 mg/m2, and total-body irradiation, 8 Gy) or conventional doses of chemotherapy.[1] The response rate in the high-dose therapy arm was 81% (CR = 22%), compared with only 57% in the standard group arm (CR = 5%, P < .001). The probability of achieving event-free and overall survival at 5 years was 28% and 52% in the high-dose therapy arm vs 10% (P = .01) and 12% (P = .03) in the conventional-dose arm. This trial confirmed the importance of complete response as a prognostic factor for overall survival.[6]

The use of peripheral blood stem cells, growth factors, and single-agent melphalan at 200 mg/m2 (vs totalbody irradiation) significantly reduced treatment-related mortality and improved the overall outcome of auto-SCT in multiple myeloma patients. In the 1980s, in an attempt to improve the results of auto-SCT, several groups used tandem high-dose therapy with auto-SCT.[7,8] Numerous phase II and III trials have shown that these strategies are feasible and well tolerated.[9-24] However, these studies were nonrandomized and contained a relatively small number of patients, making it difficult to prove that tandem transplant is more effective than single high-dose therapy and auto-SCT (Table 1).

Nonrandomized Trials of Tandem Auto-SCT

FIGURE 1

Outcome in 'Total Therapy' Patients

In the early 1990s, Barlogie's group in Little Rock, Arkansas, adopted a "total therapy" program for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. The program consisted of a series of intensive induction regimens using the non-cross-resistant drugs vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone (VAD) * 4 cycles, etoposide, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin, followed by high-dose cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar) and stem cell collection, followed by tandem auto-SCT (irrespective of the response to induction). Upon hematologic recovery, patients received maintenance therapy with interferon.

Several updates of these data have been published.[3,7,24,25] The investigators noted a progressive increase in complete and partial response rates with each stage of the study: from 5% and 34% after VAD, to 15% and 65% at the end of induction, to 26% and 75% after the first auto-SCT, and to 41% and 83% after the second. Median event-free and overall survivals were 68 and 43 months, respectively. Median time to disease progression was 52 months (Figure 1).

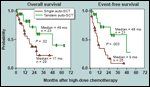

FIGURE 2

Survival Curves for 'Total Therapy' Patients

On multivariate analysis, superior event-free and overall survivals were observed in the absence of unfavorable karyotype (11q breakpoint abnormalities, -13 or 13q) and low beta-2-microglobulin levels (Figure 2). Median CR duration was 50 months, and CR was significantly longer with early onset of remission and favorable karyotype. Time-dependent analysis suggested that administration of the second auto-SCT within 6 months after the first extended both eventfree and overall survivals significantly, independent of karyotype or beta- 2-microglobulin levels.

The outcome in 1,000 multiple myeloma patients who received tandem auto-SCT was recently reported by Barlogie's group.[23] One factor associated with prolonged event-free survival (> 5 years), in addition to the absence of chromosome 11 or 13 abnormalities and low beta-2-microglobulin levels (< 2.5 mg/L) was pretransplant chemotherapy of less than 12 months at the time of first auto- SCT. Recently, Tricot et al reported that a small group of patients (n = 46) remained in continuous remission up to 7 years after auto-SCT. Of 515 patients, those without unfavorable risk factors (25%) had an event-free survival rate exceeding 35%, compared with 15%, 10%, and 0% for patients with one (43%), two (27%), or three (5%) risk factors, respectively.[ 26] These data show that patients with high-risk features should be considered for novel therapeutic interventions, as tandem auto-SCT does not significantly improve eventfree or overall survival.

Other studies using tandem auto-SCT reported similar long-term survival rates.[27] The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation recently updated its transplantation registry data on a total of 8,362 multiple myeloma patients.[19] Only a subset of newly diagnosed patients (n = 441) received tandem cycles of high-dose therapy (their selection criteria were not reported). The investigators noted a trend toward improved survival at 7 years among patients receiving one vs two auto-SCTs (39% vs 57%, P = .1). The median overall survival following auto-SCT was 7.1 years in the tandem group and 5.6 years in the single auto-SCT groups. Although the majority of patients relapsed within the first 5 years after auto-SCT, a plateau was noted in event-free and overall survival after 7 to 8 years, thus supporting the possibility of "cure" in a small subset of patients.

Randomized Trials of Tandem Auto-SCT

Few randomized trials have compared single to tandem auto-SCT in patients with multiple myeloma. These studies vary significantly in design and eligibility criteria, and all are in different stages of maturation, making it difficult to define the benefits of tandem auto-SCT.

Bologna 96 Trial

The first is the Bologna 96 trial,[15] which included 192 newly diagnosed myeloma patients from 37 centers who received four cycles of VAD followed by cyclophosphamide at 7 g/m2 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF [Neupogen]) for stem cell mobilization. Responding patients were randomized to single auto-SCT (n = 98, melphalan, 200 mg/m2) vs tandem auto-SCT (n = 94, melphalan at 200 mg/m2 for the first transplant, and melphalan at 200 mg/m2 and busulfan [Busulfex, Myleran] at 12 mg/kg for the second), followed by interferon maintenance therapy. The median age of patients was 52 years; 83% had stage II or III disease, and 13% had beta-2-microglobulin levels > 6 mg/L. Ninety percent of patients received the first and 66% received the second auto-SCT.

On intent-to-treat analysis, a CR was achieved in 6% of patients after VAD chemotherapy, in 12% after cyclophosphamide, in 27% after the first transplant, and in 25% after the second transplant. Among patients who actually received both transplants, the CR rate was 35%. The mortality rate after first transplant was 1.7%, and no deaths were reported after the second transplant. Two-year survival was similar in both groups (90%), with a trend toward a longer relapse-free and event-free survival in patients receiving tandem auto-SCT. When the analysis was restricted to patients who received both transplants, this improvement was statistically significant (P = .03).

IFM 94-02

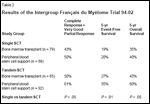

TABLE 2

Results of the Intergroupe Franais du Mylome Trial 94-02

The Intergroupe Franais du Mylome (IFM) has reported an interim analysis of the IFM 94-02 trial.[12,28] This trial enrolled 403 newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients, all younger than age 60 years. After three cycles of VAD, responding patients (n = 344) were randomized to receive a single SCT (n = 167, melphalan at 140 mg/m2 and 8 Gy of total-body irradiation) or tandem transplants (n = 177, melphalan at 140 mg/m2 for the first, and melphalan at 140 mg/m2 and 8 Gy of total-body irradiation for the second SCT). Patients were further randomized to receive either bone marrow transplant or peripheral blood stem cells as follows: In the single-SCT arm, group A1 (n = 79) received bone marrow transplant and group A2 (n = 88) received peripheral blood stem cells; in the tandem-SCT arm, group B1 (n = 85) received bone marrow transplant and group B2 (n = 92) received peripheral blood stem cells (Table 2). Eighty-one percent of patients received a single auto-SCT and 75% received tandem auto-SCT.

There was no difference in CR rate between the two arms (39 vs 49%, P = .06%). Early analysis showed that the median event-free and overall survivals were comparable in both arms (single SCT, 24 and 48 months; tandem SCT, 30 and 54 months, respectively). With a median follow-up of 3 years, among patients who had been randomized to auto-SCT, those with a beta-2-microglobulin level < 3 mg/L at diagnosis showed an improvement in overall survival (69% vs 84%, P = .05). At a median follow-up of 4 years among patients surviving more than 3 years after diagnosis, those who received a tandem auto-SCT (n = 98) had a significantly better overall survival at 5 years than those who received a single transplant (n = 100)-70% vs 85% (P = .01). The final analysis proved that at 7 years, patients receiving tandem auto- SCT had a better event-free survival (20% vs 10%, P < .03) and overall survival (42% vs 21%, P = .01).[49]

Mylome-Autogreffe Study

The French group, Mylome- Autogreffe, randomized 193 newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients to single vs tandem SCT, and to receive unselected vs CD34-positive- enriched peripheral blood stem cell grafts.[20] Initial therapy consisted of high-dose steroids followed by mobilization with cyclophosphamide at 4 g/m2 and lenograstim at 10 μg/kg/d. In the CD34-selected arm, the researchers reported a "purity of 95%" with more than a 2-log tumor depletion.

In the single-SCT group, patients received a VAD-like regimen * 3 followed by a multidrug combination consisting of carmustine (BCNU), etoposide, melphalan at 140 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at 60 g/m2, along with total-body irradiation (12 Gy in six fractions). In the tandem- SCT group, patients received melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (always with unselected peripheral blood stem cells) followed 2 to 3 months later by a second cycle of melphalan at 140 mg/m2, etoposide at 30 mg/m2, and 12 Gy of total-body irradiation. In both arms, when total-body irradiation was used, patients received selected or nonselected peripheral blood stem cells, depending on randomization.

At a median follow-up of 27 months, data on 193 patients have been analyzed. The overall response rate was 42% after a single SCT and 37% after a tandem SCT. Toxic death rates were 9% and 7%, respectively. To date, there is no difference in treatment-related mortality, disease response, and patient outcome between groups. Interestingly, posttransplant hematologic engraftment was similar in both the selected and nonselected groups. However, immunologic recovery was delayed in the CD34-positive-selected group, with an increase in the incidence of serious infections.

Immune Reconstitution After Tandem Auto-SCT

B- and T-cell counts (and possibly functions) return to normal within 4 months after auto-SCT.[10,19] However, a low CD4/CD8 ratio continues for up to 1 year. This is secondary to a persistent increase in CD8-positive subsets and a constant decrease in CD4-positive subsets, thus making patients susceptible to infections. Natural killer cell levels return to normal within 1 month after tandem auto-SCT. According to some trials,[10,19] immune reconstitution is similar after single and tandem auto-SCT. However, as mentioned earlier, the French trial did show a difference in immunologic recovery, with an increase of serious infections in the tandem-SCT, CD34-selected group.[20]

Cost of Tandem Auto-SCT

A careful assessment of the costbenefit ratio of any procedure is crucial when an expensive procedure is to be promoted to insurance companies and patients. One way to cut costs is to decrease or eliminate hospitalization without affecting patient outcome.[29,30]

In the "total therapy" program at the University of Arkansas, 91 of 251 patients received 118 auto-SCTs on an outpatient basis.[31] These patients had a better performance status than those treated as inpatients and generally were more independent. There was no difference in overall outcome between hospitalized and outpatient transplants. Of those undergoing outpatient procedures, 21% required hospitalization (median: 9 days), mostly for neutropenic fever.

The development of allogeneic, nonmyeloablative transplants has allowed the procedure to be performed more often on an outpatient basis and with significant savings. A recent report addressed the possibility of proceeding with both auto- and allo-SCT in an ambulatory setting.[ 32] It must be emphasized, however, that not all patients are eligible for ambulatory therapy.

Patient Selection for Tandem Auto-SCT

Since the early trials of auto-SCT, patient selection has been a crucial issue. Initially, like any new cancer therapy, the procedure was performed in relapsed and refractory patients. However, with the introduction of peripheral blood stem cells and growth factors, mortality decreased and overall outcome improved significantly. Today,

auto-SCT is considered the standard of care for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. However, most centers limit high-dose therapy to younger patients (≤ 55-65 years old) with normal renal, cardiac, and pulmonary functions. Such criteria exclude more than 50% of all multiple myeloma patients. The issue is more complicated for tandem transplants, and even in younger selected patients, only 66% and 75% of those randomized to tandem SCT in the Bologna 96 and IFM 94-02 trials actually received both transplants.[15,28]

Auto-SCT for Renal Failure

Abnormal renal function is the presenting feature in 20% of patients with multiple myeloma, and 2% to 3% will require dialysis.[33-35] In conventional chemotherapy trials, renal failure is a poor prognostic factor. Patients with renal insufficiency receive reduced doses of conventional chemotherapy and generally have been excluded from high-dose therapy trials. Nevertheless, the feasibility and efficacy of high-dose therapy and auto-SCT in these patients have been established.[36,37]

FIGURE 3

Survival Among Renal Failure Patients

Initial reports supported administration of melphalan at 200 mg/m2 to patients with renal failure. However, subsequent analysis showed that lower doses of melphalan (140 mg/m2) were better tolerated, did not adversely affect event-free and overall survival compared to full melphalan conditioning (200 mg/m2), and allowed for administration of repeated cycles of high-dose therapy.[22]

Unfortunately, the second cycle of high-dose therapy and auto-SCT adversely affected overall survival in this population (Figure 3). The quality of stem cell collection and engraftment were not affected by renal failure. Improvement in renal function has been reported after highdose therapy, but most patients remain dialysis-dependent. Therefore, abnormal renal function per se is not a contraindication to auto-SCT, but a second cycle of high-dose therapy should not be administered in this setting (outside of clinical trials) until its safety has been established.

Auto-SCT for Elderly Patients

Several studies have confirmed the efficacy of high-dose therapy in "elderly" patients with multiple myeloma.[ 16,21,38-41] However, it should be emphasized that the randomized experience with tandem therapy has included mainly relatively young patients.

Recently, the outcome in patients older than age 70 was reported.[21] A total of 70 patients over 70 years old (34 with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma and 36 with refractory disease) with a median age of 72 years received melphalan at 200 mg/m2 (n = 25) or melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (n = 45). Transplant-related mortality in the higher-dose group was 16% vs 2% in the lower-dose group (P = .05), with 44% of patients proceeding to a second SCT. The CR rates were 20% after the first auto- SCT and 27% after the second. Administration of a second transplant was biased by patient selection but significantly improved event-free and overall survival (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Survival Among the Elderly

Palumbo et al reported on 71 patients (median age: 64) who received a lower dose of melphalan (100 mg/m2) every 2 months for two to three cycles.[16] Depending on response, those with less than a complete response after the second transplant received a third cycle. The outcome was compared to 71 controls- matched for age and beta-2- microglobulin levels-who were treated with conventional melphalan and prednisone.

The CR rates were 47% after melphalan at 100 mg/m2 and 5% after chemotherapy. The median event-free survival was 34 vs 17.7 months in favor of high-dose therapy (P < .001). Median overall survival was 56+ months for melphalan and 48 months for chemotherapy (P = .01). A total of 89% of patients completed the program, and no toxic deaths occurred. Whether the use of protective agents (eg, amifostine [Ethyol]) will allow these elderly patients to receive higher doses of melphalan safely remains to be studied.[42]

Tandem 'Auto/Allo' Transplants

The curative potential of allo-SCT in multiple myeloma is largely mediated by the immune graft-vs-myeloma effect.[43,44] However, the role of allo-SCT has been hindered by high treatment-related mortality in the first 100 days, ranging from 30% to 50% in most series. Overall, 30% to 50% of those who achieve CR and are alive at 1 year remain disease free 3 to 6 years after allo-SCT- some in well-documented molecular remissions, who are probably cured.

Cooperative groups and several single institutions have reported the results of allo-SCT using traditional, myeloablative regimens in patients with multiple myeloma. For example, the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMTR) reported results for 162 patients who underwent allo-SCT for multiple myeloma.[45] The median age was 43 years, and 52% had chemotherapy- sensitive disease at the time of transplant. The majority (72%) received high-dose chemotherapy; a few received total-body irradiation. Graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine with either methotrexate (48%) or other agents (20%). T-cell depletion was used in 33% of patients. The overall treatment-related mortality rate was 25%, with death resulting from infection, interstitial pneumonitis, or GVHD. The overall CR rate was 44%, and the actuarial overall survival at 4 and 9 years was 32% and 18%, respectively. Event-free survival was 34% at 6 years for patients who achieved a CR.

Similar experience was reported by the investigators from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center on 80 patients who underwent allo-SCT for multiple myeloma, most of whom had chemotherapy-refractory disease.[ 46] A total of 60 patients received bone marrow from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donors, and 20 patients received mismatched or unrelated grafts. Conditioning regimens were busulfan and cyclophosphamide (n = 57) or total-body irradiation (n = 23). Prophylaxis for GVHD consisted of cyclosporine and methotrexate (56%) or prednisone (37%). The treatment-related mortality rate was 56%, secondary to infections, veno-occlusive disease, and complications of GVHD. The CR rate was an impressive 36% in these refractory patients. Overall and event-free survivals were 20% and 16%, respectively, at 5 years after allo-SCT. In a recent update that included 136 patients, the probabilities of survival and event-free survival at 5 years were 22% and 14%, respectively, and for those who achieved a CR (34%), these 5-year rates were 48% and 37%.

In general, the results from many other centers have been similar. Allo- SCT is associated with CR rates ranging from 22% to 50%. In all trials, treatment-related mortality has been high, related primarily to the complications of GVHD, infection, and relapse. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center demonstrated that advancedstage disease is associated with inferior outcomes after allo-SCT and that allo-SCT is more successful if it is performed early after diagnosis and before extensive therapy. Unfortunately, the treatment-related mortality of allografting is high, and methods to improve outcome are needed before this therapy can be applied in newly diagnosed patients.

Nonmyeloablative Immunosuppressive Regimens

One recent development that has facilitated the exploration of graftvs- tumor effects and potentially minimized the morbidity and mortality associated with GVHD is the use of nonmyeloablative immunosuppressive regimens. These regimens appear to be tolerable and show encouraging short-term results in heavily pretreated patients with hematologic toxicities.

At the University of Arkansas, a nonmyeloablative preparative regimen of melphalan 100 mg/m2 with cyclosporine for GVHD prophylaxis can establish a durable and stable allo-engraftment in heavily treated multiple myeloma patients (n = 16) who have relapsed after at least one auto-SCT.[47] Preemptive donor lymphocyte infusions were scheduled on days 21, 42, and 112 to maximize graft-vs-tumor effect and to establish full donor chimerism. None of these patients was a candidate for conventional myeloablative conditioning because of age, comorbid conditions, and/or the extent of prior therapy.

Melphalan, 100 mg/m2, resulted in mild toxicity and brief hospitalization. Treatment-related mortality was much lower in this study than in historical controls receiving myeloablative- conditioning therapy (18%). No patients died in the 100 days immediately following allo-SCT. The incidence of infectious complications- especially cytomegalovirus reactivation after engraftment-was high, as reported previously with nonmyeloablative transplants.

The incidence of acute GVHD in these patients was comparable to that seen with conventional allo-SCT and occurred mostly after donor lymphocyte infusion or withdrawal of cyclosporine. We found that despite the advanced refractory disease of most of our patients at the time of allo- SCT, 75% had a remarkable response (ie, at least a partial response) and 30% achieved a stringently defined complete response. A graft-vs-myeloma effect must be responsible for these responses, because patients were refractory to or had relapsed after high-dose therapy.

• Follow-up Investigation-In a recent update, 31 multiple myeloma patients had received allografts from HLA-matched siblings (n = 25) or unrelated donors (n = 6) using melphalanbased conditioning and cyclosporine for GVHD prophylaxis.[48] Seventeen patients had progressive disease, 14 had chemosensitive disease (including 8 with responsive relapse), and 30 had received one (n = 13) or at least two (n = 17) prior auto-SCTs. The median age was 56 years (range: 38- 69); 21 patients had a chromosome 13 abnormality, and 2 were hemodialysis- dependent. Blood and bone marrow grafts were administered to 28 and 3 patients, respectively, and 18 patients received donor lymphocyte infusions either to attain full donor chimerism (n = 6) or to eradicate residual disease (n = 12). By day 100, 25 of 28 patients (89%) were full-donor chimeras, 1 was a mixed chimera, and 2 had autologous reconstitution. Acute GVHD developed in 18 (58%) patients, with 10 progressing to chronic GVHD (limited in 6 and extensive in 4).

FIGURE 5

Effect of Disease Status and Number of Auto-SCTs

At a median follow-up of 6 months, 19 of 31 patients (61%) achieved a CR or near CR, and 12 patients (39%) died-3 of progressive disease, 3 of early (before day 100) treatmentrelated complications, and 6 of late treatment-related complications. Median overall survival was 15 months. At 1 year, patients in whom the allograft was planned after one (vs two or more) prior auto-SCT had a significantly longer event-free (86% vs 31%, P = .01) and overall (86% vs 48%, P = .04) survival (Figure 5). Allografts performed early in the disease course after one prior auto-SCT appeared to be better tolerated and provided excellent disease control in high-risk patients (as defined by beta-2-microglobulin and chromosome 13 abnormalities). However, the procedure is still associated with significant GVHD.

Upfront 'Auto/Allo' SCT

The concept of tandem "auto/allo" SCT has been applied upfront to patients with multiple myeloma (irrespective of their disease risk) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center.[ 32] A total of 32 patients (43% with refractory disease; median age: 55 years) received melphalan at 200 mg/m2 followed by autologous stem cells. Between 40 and 120 days later, they received total-body irradiation (200 cGy), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), and cyclosporine plus peripheral blood stem cells from HLA-identical siblings. Following auto-SCT, one patient died of cytomegalovirus pneumonia on day 31. Thereafter, 31 patients received allografts. Patients were 90% chimeric by day 28, and 99% by day 84.

Median length of hospitalization was only 4 days after auto-SCT and 0 days after allo-SCT. No severe neutropenia or thrombocytopenia was seen after the allograft. Median follow-up from the first transplant was 423 days. The mortality rate at 100 days was 6%: One patient died after auto-SCT and one died of progressive disease after the allograft. Acute grade II-IV GVHD was present in 45%, and 55% developed chronic GVHD.

The overall response rate of 84% included a 53% CR rate and only two reports of progressive disease. At the time of the report, six patients had died, five after the allograft-one from disease progression, three from GVHD complications, and one from encephalopathy. Although these results are encouraging, further follow-up and confirmatory studies are necessary to better characterize the role of auto- SCT followed by allo-SCT.

Conclusions

REFERENCE GUIDE

Therapeutic Agents

Mentioned in This Article

Amifostine (Ethyol)

Busulfan (Myleran, Busulfex)

Carmustine (BCNU)

Cisplatin

Cyclophosphamide

(Cytoxan, Neosar)

Cyclosporine

Cytarabine

Dexamethasone

Doxorubicin

Etoposide

Granulocyte colony-stimulating

factor (G-CSF [Neupogen])

Interferon

Lenograstim

Melphalan (Alkeran)

Methotrexate

Mycophenolate mofetil

(CellCept)

Prednisone

Thalidomide (Thalomid)

Brand names are listed in parentheses only if a drug is not available generically and is marketed as no more than two trademarked or registered products. More familiar alternative generic designations may also be included parenthetically.

The central issue of tandem SCTs in multiple myeloma, whether they be auto- or allo-SCTs, lies in defining the subsets of patients who will benefit from the procedure, as a single cycle of SCT may produce a prolonged remission in few good-risk patients. The additional benefit of tandem transplants and the wider implementation of this strategy in highrisk patients must be weighed against the patient's ability to undergo such therapy and the cost-benefit ratio. Although high-risk patients (defined by cytogenetic abnormalities and high beta-2-microglobulin) can achieve a CR following tandem auto-SCT, most have a short event-free survival of less than 9 months. When the cost, duration, and toxicities of therapy are considered, it is clear that tandem auto-SCTs provide minimal benefit to this group of patients.

For this reason, we believe that in the setting of a clinical trial, high-risk multiple myeloma patients with a suitable allogeneic donor and/or all patients who achieve less than a partial response to the first cycle of high-dose therapy should be offered a subsequent, planned nonmyeloablative allo-SCT. Until mature data on nonmyeloablative therapy are available, it is reasonable to offer good-risk patients with chemosensitive disease-and even those good-risk patients with an allogeneic donor available-a planned tandem auto-SCT upfront. A better understanding and differentiation of the graft-vs-myeloma effect from GVHD may further help optimize use of the tandem autologous and nonmyeloablative approach.

The use of conventional therapy such as melphalan/prednisone is currently being replaced by high-dose therapy and possibly tandem SCT in some patients. The final reports of the Bologna 96, IFM 94-02, and Mylome-Autogreffe trials may change the standard of care for this disease and provide information on whether multiple myeloma can be "cured" or transformed into a chronic and indolent disease. Other strategies, such as including thalidomide (Thalomid) in the transplant regimen and using posttransplant consolidation chemotherapy or other novel agents, will help improve the results of auto-SCT.

Disclosures:

The author(s) have no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

1.

Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, etal: A prospective, randomized trial of autologousbone marrow transplantation and chemotherapyin multiple myeloma. IntergroupeFrancais du Myelome. N Engl J Med 335:91-97, 1996.

2.

Lemoli RM, Martinelli G, Zamagni E,et al: Engraftment, clinical, and molecularfollow-up of patients with multiple myelomawho were reinfused with highly purifiedCD34+ cells to support single or tandem highdosechemotherapy. Blood 95:2234-2239,2000.

3.

Barlogie B, Jagannath S, Desikan KR, etal: Total therapy with tandem transplants fornewly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood93:55-65, 1999.

4.

Fassas A, Tricot G: Results of high-dosetreatment with autologous stem cell support inpatients with multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol38:231-242, 2001.

5.

McElwain TJ, Powles RL: High-dose intravenousmelphalan for plasma-cell leukaemiaand myeloma. Lancet 2:822-824, 1983.

6.

Moreau P, Facon T, Attal M, et al: Comparisonof 200 mg/m

2

melphalan and 8 Gytotal body irradiation plus 140 mg/m

2

melphalanas conditioning regimens for peripheralblood stem cell transplantation in patientswith newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Finalanalysis of the Intergroupe Francophonedu Myelome 9502 randomized trial. Blood99:731-735, 2002.

7.

Vesole DH, Barlogie B, Jagannath S, etal: High-dose therapy for refractory multiplemyeloma: Improved prognosis with better supportivecare and double transplants. Blood84:950-956, 1994.

8.

Harousseau JL, Milpied N, Laporte JP, etal: Double-intensive therapy in high-risk multiplemyeloma. Blood 79:2827-2833, 1992.

9.

Laurenti L, Sica S, Cicconi S, et al: Immunologicalshort-term reconstitution after tandemunselected peripheral blood progenitor celltransplantation for multiple myeloma. Haematologica85:782-784, 2000.

10.

Steingrimsdottir H, Gruber A, BjorkholmM, et al: Immune reconstitution after autologoushematopoietic stem cell transplantation inrelation to underlying disease, type of highdosetherapy and infectious complications.Haematologica 85:832-838, 2000.

11.

Reece DE, Hale GA, Howard DS, et al:Treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) patients(PTS) with tandem autologous stem cell transplantation(ASCT) using high-dose (HD) melphalan(MEL) followed by busulfan (BU)(abstract 57). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20:15a,2001.

12.

Attal M, Harousseau J, Facon T, et al:Single versus double transplantation in myeloma:A prospective randomized trial of theInter Groupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM)(abstract 2393). Blood 96(suppl 1):557a,2000.

13.

Colombat P, Milpied N, Laporte JP, etal: Three courses of high dose therapy. Feasibilityin the treatment of multiple myeloma-a"France autogreffe" study. Cancer 74:2930-2934, 1994.

14.

Huijgens PC, Dekker-Van Roessel HM,Jonkhoff AR, et al: High-dose melphalan withG-CSF-stimulated whole blood rescue followedby stem cell harvesting and busulphan/cyclophosphamidewith autologous stem cell transplantationin multiple myeloma. Bone MarrowTransplant 27:925-931, 2001.

15.

Tosi P, Cavo M, Zamagni E, et al: Amulticentric randomized clinical trial comparingsingle vs double autologous peripheralblood stem cell transplantation for patients withnewly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Results ofan interim analysis (abstract 3155). Blood94(suppl 1):715a, 1999.

16.

Palumbo A, Triolo S, Argentino C, et al:Dose-intensive melphalan with stem cell support(MEL100) is superior to standard treatmentin elderly myeloma patients. Blood94:1248-1253, 1999.

17.

Björkstrand B, Ljungman P, Bird JM, etal: Double high-dose chemoradiotherapy withautologous stem cell transplantation can inducemolecular remissions in multiple myeloma.Bone Marrow Transplant 15:367-371,1995.

18.

Morris TCM, Svensson H, BjörkstrandB, et al: If double autologous PBSC transplantshave a role in myeloma when are they bestperformed? An EBMT Registry study (abstract3447). Blood 96(suppl 1):798a, 2000.

19.

Björkstrand B: European Group forBlood and Marrow Transplantation Registrystudies in multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol38:219-225, 2001.

20.

Fermand J-P, Marolleau J-P, Alberti C,et al: In single versus tandem high dose therapy(HDT) supported with autologous blood stemcells (ABSC) transplantation using unselectedor CD34 enriched ABSC: Preliminary resultsof a two by two designed randomized trial in230 young patients with multiple myeloma(MM). Blood 98(suppl 1):815a, 2001.

21.

Badros A, Barlogie B, Siegel E, et al:Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderlymultiple myeloma patients over the age of 70years. Br J Haematol 114:600-607, 2001.

22.

Badros A, Barlogie B, Siegel E, et al:Results of autologous stem cell transplant inmultiple myeloma patients with renal failure.Br J Haematol 114:822-829, 2001.

23.

Desikan R, Barlogie B, Sawyer J, et al:Results of high-dose therapy for 1000 patientswith multiple myeloma: Durable complete remissionsand superior survival in the absenceof chromosome 13 abnormalities. Blood95:4008-4010, 2000.

24.

Barlogie B, Jagannath S, Vesole DH, etal: Superiority of tandem autologous transplantationover standard therapy for previously untreatedmultiple myeloma. Blood 89:789-793,1997.

25.

Vesole DH, Tricot G, Jagannath S, et al:Autotransplants in multiple myeloma: Whathave we learned? Blood 88:838-847, 1996.

26.

Tricot G, Spencer T, Sawyer J, et al:Predicting long term (=/> 5 yr) event-free survivalin multiple myeloma patients followingplanned tandem autotransplants. Br J Haematol116:211-217, 2002.

27.

Sirohi B, Kulkarni S, Powles R: Someearly phase II trials in previously untreated multiple myeloma: The Royal Marsden experience.Semin Hematol 38:209-218, 2001.

28.

Attal M, Harousseau JL: Randomizedtrial experience of the Intergroupe Francophonedu Myelome. Semin Hematol 38:226-30,2001.

29.

Meisenberg BR, Ferran K, HollenbachK, et al: Reduced charges and costs associatedwith outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation.Bone Marrow Transplant 21:927-932,1998.

30.

Gómez-Almaguer D, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ,Ruiz-Argüelles A, et al: Hematopoietic stemcell allografts using a non-myeloablative conditioningregimen can be safely performed onan outpatient basis: Report of four cases. BoneMarrow Transplant 25:131-133, 2000.

31.

Jagannath S, Vesole DH, Zhang M, et al:Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of outpatientautotransplants in multiple myeloma. BoneMarrow Transplant 20:445-50, 1997.

32.

Maloney DG, Sahebi F, Stockerl-GoldsteinKE, et al: Combining and allogeneic graftvs-myeloma effect with high-dose autologousstem cell rescue in the treatment of multiplemyeloma (abstract 1822). Blood 98(suppl1):434a, 2001.

33.

DeFronzo RA, Cooke CR, Wright JR, etal: Renal function in patients with multiplemyeloma. Medicine (Baltimore) 57:151-166,1978.

34.

Johnson WJ, Kyle RA, Pineda AA, et al:Treatment of renal failure associated with multiplemyeloma. Plasmapheresis, hemodialysis,and chemotherapy. Arch Intern Med 150:863-869, 1990.

35.

Durie BG, Salmon SE: A clinical stagingsystem for multiple myeloma. Correlation ofmeasured myeloma cell mass with presentingclinical features, response to treatment, and survival.Cancer 36:842-854, 1975.

36.

Tricot G, Alberts DS, Johnson C, et al:Safety of autotransplants with high-dose melphalanin renal failure: A pharmacokinetic andtoxicity study. Clin Cancer Res 2:947-952,1996.

37.

Tosi P, Zamagni E, Ronconi S, et al:Safety of autologous hematopoietic stem celltransplantation in patients with multiple myelomaand chronic renal failure. Leukemia14:1310-1313, 2000.

38.

Siegel DS, Desikan KR, Mehta J, et al:Age is not a prognostic variable with autotransplantsfor multiple myeloma. Blood 93:51-54,1999.

39.

Kusnierz-Glaz CR, Schlegel PG, WongRM, et al: Influence of age on the outcome of500 autologous bone marrow transplant proceduresfor hematologic malignancies. J ClinOncol 15:18-25, 1997.

40.

Powles R, Raje N, Milan S, et al: Outcomeassessment of a population-based groupof 195 unselected myeloma patients under70 years of age offered intensive treatment.Bone Marrow Transplant 20:435-443,1997.

41.

Sirohi B, Powles R, Treleaven J, et al:The role of autologous transplantation in patientswith multiple myeloma aged 65 yearsand over. Bone Marrow Transplant 25:533-539, 2000.

42.

Reece DE, Filicko J, Flomemberg N, etal: Use of melphalan 280 mg/m

2

plus amifostinecytoprotection and autologous stem celltransplantation in multiple myeloma patients.Blood 98(suppl 1):196a, 2001.

43.

Tricot G, Vesole DH, Jagannath S, et al:Graft-versus-myeloma effect: Proof of principle.Blood 87:1196-1198, 1996.

44.

Bensinger WI, Maloney D, Storb R: Allogeneichematopoietic cell transplantation formultiple myeloma. Semin Hematol 38:243-249,2001.

45.

Gahrton G, Tura S, Ljungman P, et al:Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation inmultiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 325:1267,1991.

46.

Bensinger WI, Buckner CD, Anasetti C,et al: Allogeneic marrow transplantation formultiple myeloma: An analysis of risk factorson outcome. Blood 88:2787-2793, 1996.

47.

Badros A, Barlogie B, Morris C, et al:High response rate in refractory and poor-riskmultiple myeloma after allotransplantation usinga nonmyeloablative conditioning regimenand donor lymphocyte infusions. Blood97:2574-2579, 2001.

48.

Badros A, Barlogie B, Siegel E, et al:Improved outcome of allogeneic transplantationin high-risk multiple myeloma patients afternonmyeloablative conditioning. J Clin Oncol20:1295-1303, 2002.

49.

Attal M, Harousseau J, Facon T, et al:Double autologous transplantation improvessurvival in multiple myeloma patients: Finalanalysis of a prospective randomized trial ofthe IFM94 (abstract 7). Blood 100(suppl),2002.

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.