Vaccines plus screening could end cervical ca

Out with the old and in with the new is a commonly followed maxim in medicine given the rapid pace of developments in diagnosis and treatment. Human papillomavirus vaccines are relative newcomers to the cervical cancer armamentarium, but they cannot be relied on to do the job on their own; screening is still a must.

Out with the old and in with the new is a commonly followed maxim in medicine given the rapid pace of developments in diagnosis and treatment. Human papillomavirus vaccines are relative newcomers to the cervical cancer armamentarium, but they cannot be relied on to do the job on their own; screening is still a must.

Richard B. Roden, PhD, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Carlos L. Santos, MD, from the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas in Lima, Peru, discussed the merits and drawbacks of HPV vaccines and standard screening during a session on female malignancies at ASCO 2009 in Orlando.

Long-term protection

The widespread vaccination of adolescents against HPV will be critical to the eradication of cervical cancer, said Dr. Roden, an associate professor in the department of pathology. “HPV virus-like particle [VLP] vaccines are very effective in preventing genital HPV infection and neoplastic disease,” he explained. “Solid protection has been observed for more than six years after vaccination, suggesting vaccine protection is likely to be long-term, although the need for a booster is not out of the question.”

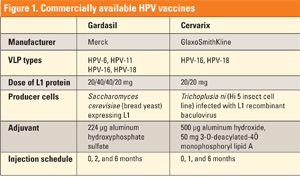

To date, two HPV vaccines are FDA-approved: Gardasil from Merck, produced in yeast, and Cervarix from GlaxoSmithKline, produced in insect cells. In October 2009, Gardasil was approved by the FDA for use in boys and men (aged 9-26) for the prevention of genital warts caused by HPV-6 and HPV-11.

Both vaccines target HPV-16 and HPV-18, the two most common oncogenic HPV types. Gardasil also targets HPV-6 and HPV-11, which cause benign genital warts (see Figure 1).

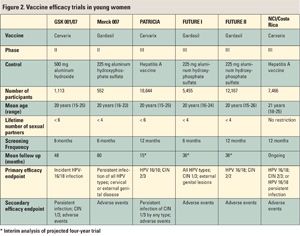

Two types of trials, efficacy trials and immunogenicity bridging trials, have contributed to the licensing of these HPV VLP vaccines. All of the six efficacy trials have been placebo-controlled (randomized 1:1 between vaccine and placebo) and double-blinded, and they have included young women (see Figure 2).

“Some of the results from these trials have been confusing to some people, and that reflects the different types of analyses that were done,” Dr. Roden said. The cohorts analyzed were:

• According to protocol (ATP)

• Intention to treat (ITT)

• Modified intention to treat (MITT)

The most clearcut study results came from ATP trials that were conducted with no protocol violations. Also, the endpoints were not counted until the intervention was completed. In ITT, endpoints were counted from the start of enrollment; these trials offer a better estimation of the impact of general use. Finally, in MITT trials, protocol violations were still counted as were endpoints that occurred after one intervention/dose. In the trials with Gardasil and Cervarix, efficacy in the ATP cohort was consistent and impressive, ranging from 96% to 100%. However, the efficacy dropped off in the MITT cohort: between 94% and 100% for the Gardasil trials and between 76% and 94% for Cervarix trials. Based on MITT/ITT analysis for any HPV type, vaccine efficacy came in at 34% in the FUTURE I study, 17% in the FUTURE II study, and 52% in the GSK 001/07 study.

“Why is this efficacy so low? These are really the expected results. The prophylactic vaccine produces somewhat type-restricted protection,” Dr. Roden said. “The vaccine does not induce the regression of established infection. Disease from prevalent infection dominated disease from incident infection in the trials that had a relatively short follow up.” In short, the vaccines are not therapeutic, he added.

The HPV vaccine has been shown to be effective in other groups, Dr. Roden said. ATP data on Gardasil have demonstrated a 90% reduction in HPV-6 and HPV-11 in women aged 24 to 45. It has also been deemed effective in adolescent boys and men (aged 16 to 23), with an approximately 85% reduction in incident, persistent six-month infection and a near 90% reduction in incident external warts caused by the main HPV types.

Finally, immunobridging studies provide rationale for vaccination in groups that were not included in the major trials, such as adolescent girls, he said. Solid protection for more than six years after vaccination suggests that the benefits are long-term.

Screening remains main option in many countries

While the evidence for the efficacy of vaccination may be solid, its widespread, global distribution is less certain at this time. In developing areas with limited resources, vaccination with the current HPV vaccines may not be an option, said Dr. Santos, who is a gynecologic oncologist at his institution. This is particularly problematic because cervical cancer is prevalent in these areas, with the highest incident mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and some Asian countries, Dr. Santos said. In half of Latin American countries, cervical cancer is the number one female malignancy.

“Let’s take a look at the development of cervical carcinogenesis in order to understand the place for secondary prevention,” he said. “This is a long-lasting process, starting with HPV infection and ending up in invasive carcinoma capable of killing the host. Fortunately, we have a long period of precancerous or premalignant lesions, usually five to 15 years, and these are easily treatable.”

There are two ways to establish a cervical cancer screening program, Dr. Santos said. An opportunistic program takes advantage of any visit that a female patient makes within her healthcare system as a chance for screening. An organized program is promoted by a central public health institution, which ensures coverage to all at risk.

The standard methodology for screening is cytology, followed by colposcopy if it is deemed necessary, followed by biopsy. This system has proved very effective in industrialized nations, Dr. Santos pointed out. He cited data from Scandinavia as an example. “Sweden and Finland get the best results in terms of reduction of the mortality rate because they have long-standing and very well organized screening programs,” he said. “Norway started screening a bit later compared to its neighbors. In Denmark, there is a mixture of opportunistic and organized screening and their results are not as good.”

Unfortunately, developing nations cannot claim such success rates, Dr. Santos said. Some of the reasons that screening has failed include:

• Failure to reach the population at risk

• Lack of sensitivity of cytologic screening

• Infrequency of repeated screening

• Inadequate management of abnormalities found at screening

• Ineffective treatment

However, some countries are having success with screening programs that work outside the confines of traditional, cytology-based methods. In Peru, a “see and treat” approach has been effective, Dr. Santos said. The 10-minute screening starts with the application of a solution of 5% acetic acid on the cervix, which will demarcate the borders of any lesion in the transformation zone. Any lesions that are found are considered high-grade and are treated immediately with cryotherapy, he said, adding that the advantage of cryotherapy is that it is an outpatient procedure that requires no anesthesia.

While HPV vaccination may not happen in developing nations for some time, HPV DNA testing is coming to the forefront as the primary screening method. HPV DNA testing offers many advantages, according to Dr. Santos. “It has a sensitivity over 95%, although it is less specific than cytology,” he said. “Another virtue of HPV DNA testing is that it has very good predictive value: having a negative HPV test means that there is little or no probability of developing a lesion in the next 10 years.”

The obstacle to using HPV testing in the developing world is cost, with the price tag on an individual test ranging from $70 to $80. But a less expensive reliable test-the careHPV at $5 per test-is on the horizon, Dr. Santos said. “This is the plan for developing countries. Women will be screened with careHPV. Those with negative studies will return in three to five years for follow-up testing. Those with positive results will be triaged the same day to visual inspection, and if necessary, will be treated with cryotherapy.”

Even after HPV vaccination goes global, screening will still be necessary, he said. Women who have been vaccinated will undergo screening with HPV DNA testing or biomarker testing later in life (around age 30), and the interval between screenings may be as long as a decade, Dr. Santos predicted.