Improving Leukoplakia Follow-Up: Information Leaflets, Habit Cessation Counseling

Enhancing patient adherence to follow-up care for leukoplakia through habit cessation counseling and patient information leaflets may reduce oral cancer risks.

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma ranks among the leading causes of mortality in India. Despite recent advancements in diagnosis and treatment across the globe, oral squamous cell carcinoma remains a prevalent neoplasm. Approximately two-thirds of cases are etiologically linked to patients’ lifestyles, notably tobacco and alcohol use.1 Early detection of premalignant and malignant lesions through screening is pivotal, especially in high-incidence regions where the majority of oral cancers stem from long-standing premalignant lesions.2,3 Delayed presentation is often attributed to a lack of public awareness about oral cancer and associated risk factors.4

Many patients in outpatient settings exhibit habit-associated lesions, particularly in rural areas. Despite counseling efforts, a significant number are reluctant to attend follow-up visits.

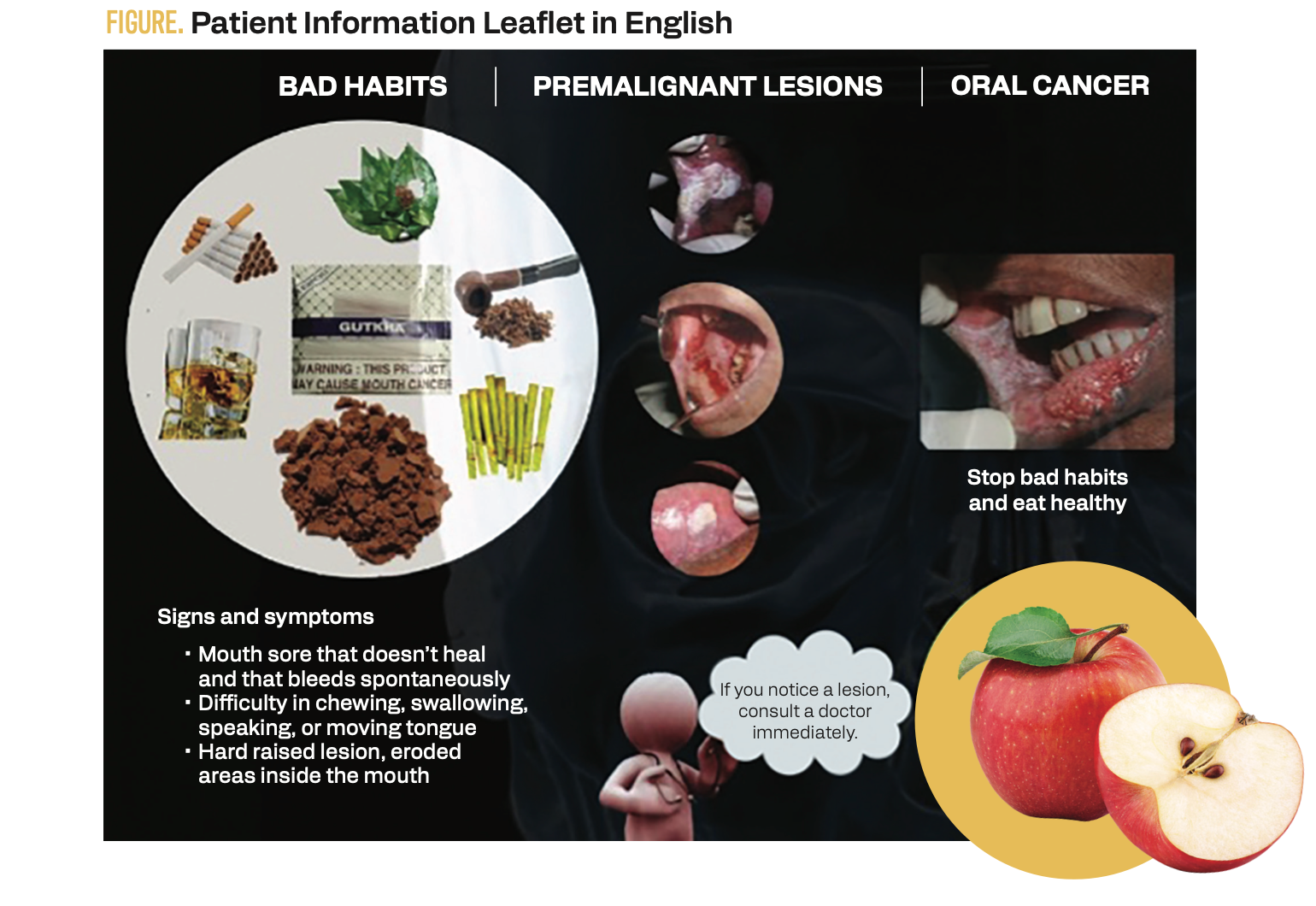

Leukoplakia, a potentially malignant disorder associated with tobacco use, presents a challenge due to its progressive risk of malignant transformation.5 Leukoplakia is characterized by white patches or lesions on the mucous membranes of the mouth.5 It poses a significant concern for patients and health care professionals. Its association with the development of oral cancers underscores the importance of vigilant monitoring and timely intervention. However, in many instances, individuals diagnosed with leukoplakia display reluctance to adhere to recommended follow-up appointments and treatments. This reluctance often stems from a lack of awareness, misconceptions, and anxieties about the condition and its potential progression.6 In response to this challenge, our study investigated the effectiveness of 2 key interventions—providing patients with informational leaflets and offering counseling services—as strategies to enhance adherence with follow-up appointments among individuals diagnosed with leukoplakia. In this quest to improve patient engagement and, ultimately, the management of leukoplakia, we aim to shed light on the potential impact of these interventions and pave the way for better-informed, more proactive, empowered patients in their journey toward oral health and cancer prevention. This study focuses on reluctant patients, distributing a patient information leaflet (PIL), and providing counseling for habit cessation to evaluate their impact on follow-up adherence and treatment adherence.

FIGURE. Patient Information Leaflet in English

Materials and Methods

This study utilized a prospective, randomized, controlled trial design to evaluate the impact of patient information leaflets and counseling on enhancing follow-up adherence in cases of leukoplakia. The study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee (Ref no: IECKVGMCH/IEC/10/22 dt.3/6/22). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and confidentiality was ensured throughout the study. The study was conducted over 6 months, and participants were followed up for 6 to 10 months.

The sample size was calculated based on the expected effect size and power analysis, considering a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%. Sixty participants with clinically diagnosed cases of leukoplakia who had been advised to undergo regular follow-up appointments were recruited from oral medicine clinics. Patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. Patients were selected based on the random sampling method and assigned to 3 groups with 20 participants as follows:

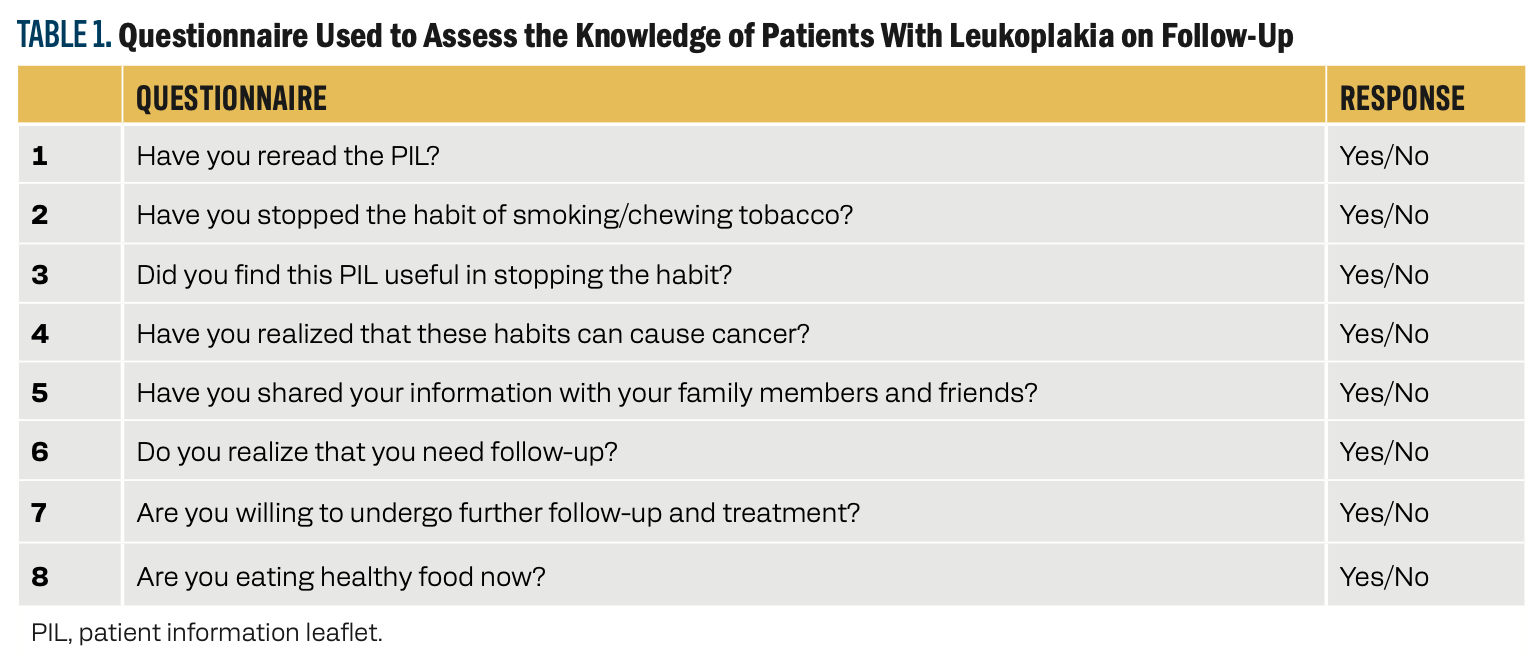

Both groups underwent follow-up assessments, including lesion reexamination and a structured questionnaire (Table 1) to gauge the impact of PILs and HCC. The questionnaires included items related to patient demographics, knowledge, attitudes, and satisfaction. Questionnaires in local languages were handed out, and patients were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of all responses. Data were collected through medical records, patient self-report questionnaires, and interviews. The obtained data were entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 23 (Licensed, JSS AHER, Mysuru). Descriptive analysis for each question of all the groups and intergroup analysis using the Kruskal-Wallis test were performed.

TABLE 1. Questionnaire Used to Assess the Knowledge of Patients With Leukoplakia on Follow-Up

Results

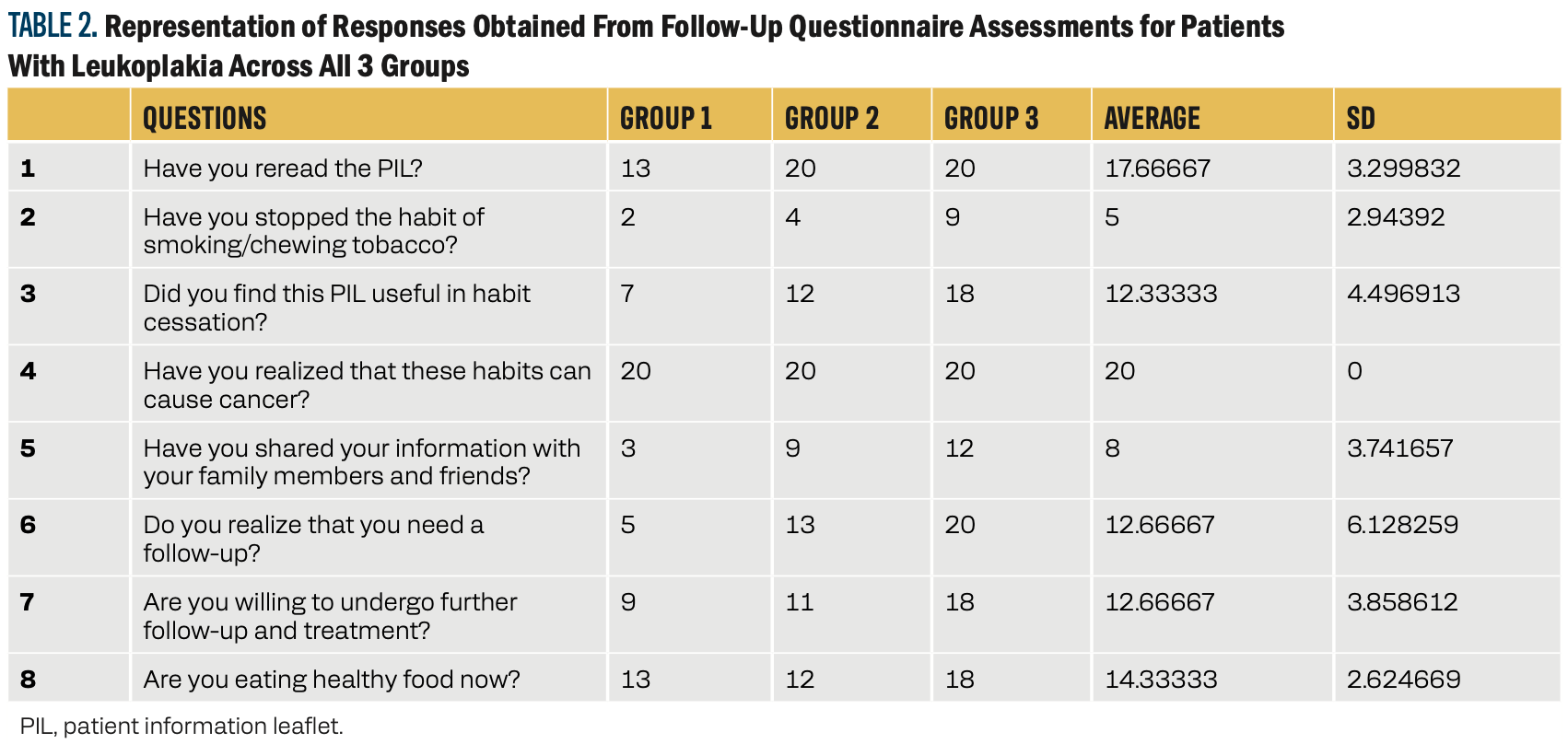

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of PILs, tobacco HCC, and both educational approaches in follow-up appointments with patients with leukoplakia. Additionally, it sought to evaluate the impact of these interventions within these 3 groups. Notably, the uniqueness of this study lies in the fact that a dentist conducted counseling at the worksite. All 60 patients attended their scheduled follow-up appointments every 2 weeks, and documentation was maintained for up to 2 follow-up sessions. Based on the responses obtained from the follow-up questionnaire assessments across the 3 groups, group 3 generally performed better in most categories, showing higher averages in several key areas, such as rereading the PIL, habit cessation, perception of PIL usefulness, information sharing, realization of the need for follow-up, willingness for further follow-up and treatment, and adoption of healthy eating habits. Group 2 demonstrated a relatively positive, favorable outcome compared with group 1, as shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Representation of Responses Obtained From Follow-Up Questionnaire Assessments for Patients With Leukoplakia Across All 3 Groups

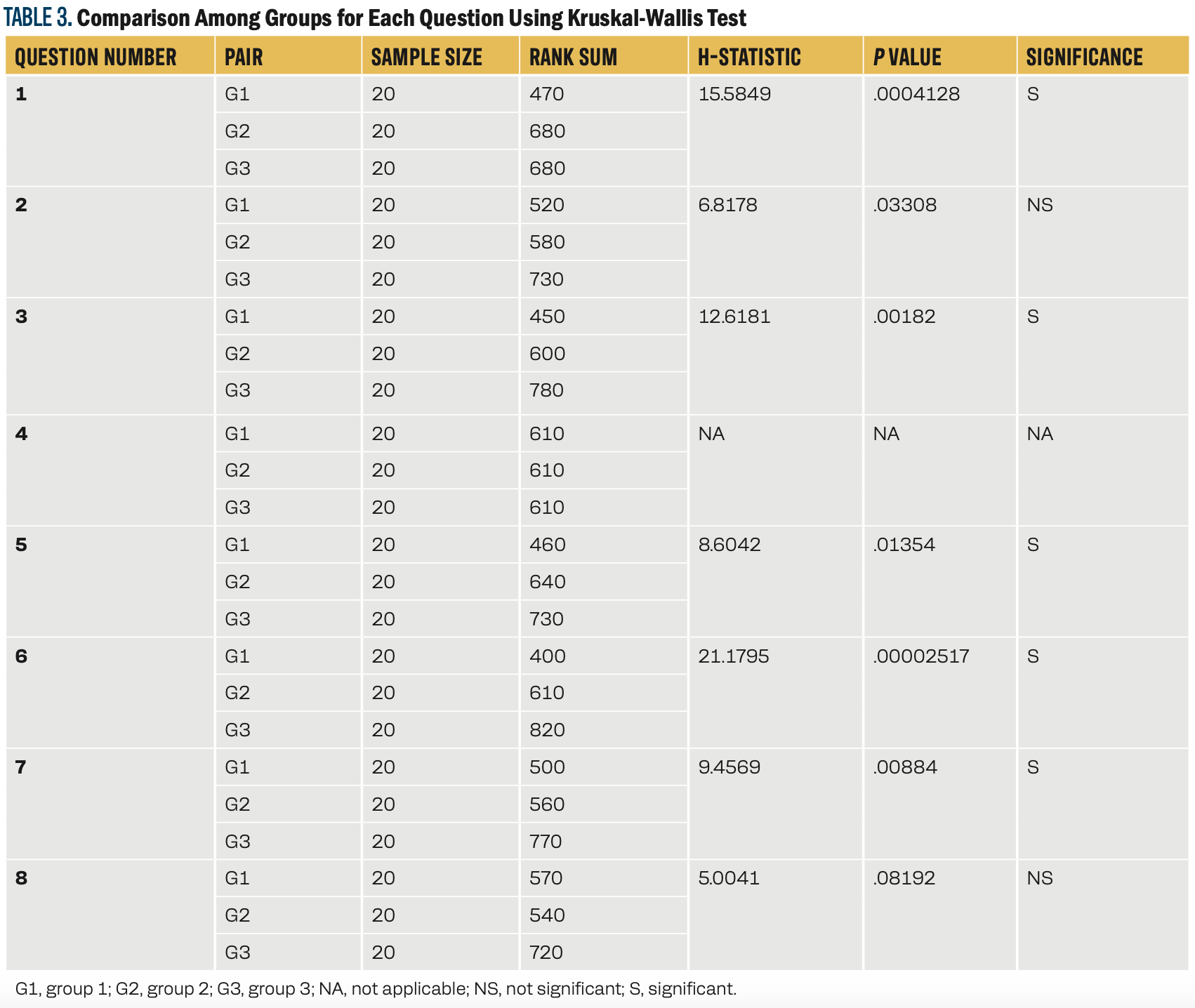

Table 3 shows statistically significant differences among the3 independent groups. Group 3 generally performed better in questions related to rereading the PIL, perceiving its usefulness, sharing information, realizing the need for follow-up, stopping the habit of smoking/chewing tobacco, eating healthy food, and being willing to undergo further follow-up and treatment. Group 2 performed better on willingness for additional follow-up and treatment than group 1.

TABLE 3. Comparison Among Groups for Each Question Using Kruskal-Wallis Test

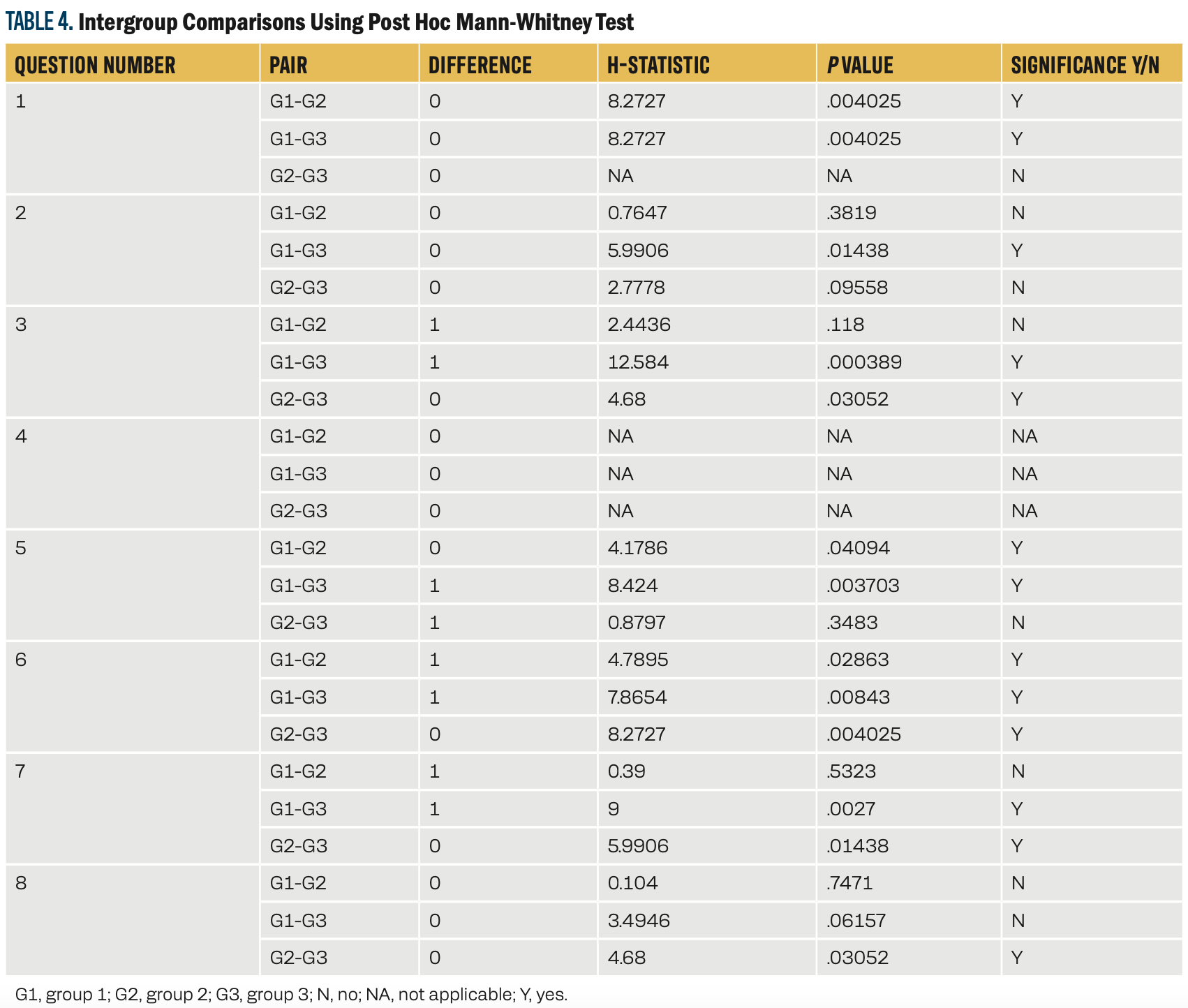

The post hoc Mann-Whitney tests indicated significant differences in responses between specific groups for several questions. Group 1 often showed differences compared with group 3, while group 2 showed fewer significant differences, as shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Intergroup Comparisons Using Post Hoc Mann-Whitney Test

Discussion

Head and neck cancer is a significant component of the global burden of cancer, with a high mortality rate. Oral leukoplakia (OL) is defined as a “white plaque of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer,” and is a well-known potentially malignant disorder of the oral mucosa.7,8 Reports indicate that when diagnosed, 15.8% to 48.0% of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma were associated with OL.9-12 The pooled estimate of the annual rate of OL malignant transformation is 1.36% in various populations and geographical areas.13 Data from one such study showed that 39 (17.9%) of 218 patients developed invasive cancer, with a mean malignant transformation period of 5.2 years.14 Motivating reluctant patients for follow-up is crucial; the PIL and the HCC were crafted to reinforce the importance of regular assessments and treatment to mitigate malignant potential.

Tobacco and alcohol are major risk factors for oral cancer, with a synergistic effect documented in epidemiological studies.15 The population-attributable risk behaviors for oral cancer of smoking and alcohol consumption have been estimated to be 80% for males, 61% for females, and 74% overall.16 All the participants in our study responded affirmatively that they acknowledged the link between bad habits and oral cancer. Dietary factors account for approximately 30% of cancers in Western countries, making them second only to tobacco as a preventable cause of cancer. Comparatively, that percentage is considered to be lower in developing countries, at around 20%.16 High intake of fruits and vegetables probably reduces the risk of oral cancer.17 Also, 87.5% of patients who followed the PIL reported a shift toward healthier eating habits.

Previous studies have explored the impact of educational materials on oral cancer awareness, with mixed results.18-21 However, our study, focusing on identified leukoplakia cases, showed positive responses regarding habit cessation, healthy eating, and willingness for follow-up. Before 2004, a study that aimed to determine the influence of a PIL on mouth cancer to improve knowledge, reduce distress, and increase intention to accept a mouth screen over2 months showed the benefit of immediate exposure to the leaflet at follow-up.19,20 Another study claimed that smokers were less knowledgeable than nonsmokers before the PIL.21 In one such study, a questionnaire was deployed to gather information on oral cancer and its risk factors and evaluate the efficacy of an educational brochure. The investigators implied that knowledge about oral cancer was not associated with age, sex, or education level, and that urban residents had better knowledge than rural residents.20 Another such study was carried out in a dental hospital, and the authors concluded that delivering information through a simple poster and leaflet campaign is likely to have a limited impact.22,23 Similarly, the current research illustrated that PILs had a significantly smaller positive influence on patients than HCC and both educational approaches.

Shibly et al illustrated the benefits of tobacco cessation in resolving oral lesions and improving overall periodontal and oral health.24 The improvement in the patient’s oral health after cessation of tobacco use was dramatic and reinforces the belief that tobacco-cessation counseling should be a routine component of the standard of care for tobacco-using patients. We also observed enhancements in lesion healing, as well as positive changes in attitude and behavior regarding tobacco use among patients with leukoplakia undergoing tobacco cessation counseling.

Limitations of the Study

Potential limitations of the study included the potential for selection bias, variations in the quality of counseling, and the relatively short follow-up period. Another constraint of the study was the use of a 1-step immunoassay cotinine test kit, which proved incapable of detecting cotinine. The positive response warrants further exploration in larger studies across dental hospital centers to maximize the benefits of PILs and HCC in enhancing patient understanding and adherence.

By employing these materials and methods, our study aimed to rigorously assess the impact of PILs and counseling on enhancing follow-up adherence in cases of leukoplakia, contributing valuable insights to managing this condition and potentially improving patient outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, our study focused on the outcome of follow-up adherence in reluctant leukoplakia cases by implementing a dual intervention strategy that includes the distribution of PILs and providing HCC. The results highlight the significant positive impact of this combined approach and its effectiveness in encouraging patients to adhere to follow-up protocols. By enhancing patient awareness through informative materials and addressing behavioral issues through counseling, we contribute valuable insights to efforts to treat leukoplakia cases. This holistic approach not only promotes better patient engagement but also promises broader applications in preventive health strategies. Future efforts should explore the sustained effects of such interventions and consider their integration into routine clinical practices to further optimize patient outcomes in the context of leukoplakia treatment.

Criteria for inclusion in the authors’/ contributors’ list

SM, SM, SH, ES, DPN: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, investigation, original draft writing, statistical analysis, validation.

VGD: Writing—review & editing, Supervision.

Author Affiliations

Shaila Mulki, PhD, MDS

Professor & Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, KVG Dental College and Hospital, Sullia - 574 237, D.K,

Karnataka, India

shailambhat123@gmail.com,

ORCID ID-0000-0002-5885-8208

Seema Mavinapalla, MDS

Lecturer, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, KVG Dental College and Hospital, Sullia - 574 237, D.K,

Karnataka, India

drseema83@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-7512-7589

Supriya Hulimane, MDS

Reader, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, KVG Dental College and Hospital, Sullia - 574 237, D.K,

Karnataka, India

supriyakarunakar@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0000-0002- 1919-7398

Elizabeth Sojan, MDS

Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Al Azhar Dental College, Al-Azhar Campus, Thodupuzha- 685605,

Kerala, India

elsasojan@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0000-0001- 5675-001X

Deviprasad Nooji, MDS

Professor, Department of Prosthodontics, KVG Dental College and Hospital, Sullia - 574 237, D.K,

Karnataka, India,

devinooji@gmail.com,

ORCID ID: 0000-0002- 5737-7154

Vidya Gowdappa Doddawad, MDS

Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, JSS Dental College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru - 570015,

Karnataka, India

dr.vidyagowdappadoddawad@jssuni.edu.in

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5204-8178

References

- Arbabi-Kalati F, Kari-Payhan S, Mokhtar A. Effect of education on promoting oral cancers knowledge of high school students in Zahedan. Int J Cancer Manag. 2017;10(11):e11320. doi:10.5812/ijcm.11320

- Gupta PC, Bhonsle RB, Murti PR, Daftary DK, Mehta FS, Pindborg JJ. An epidemiologic assessment of cancer risk in oral precancerous lesions in India with special reference to nodular leukoplakia. Cancer. 1989;63:2247-2252. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2247::aid-cncr2820631132>3.0.co;2-d

- Lumerman H, Freedman P, Kerpel S. Oral epithelial dysplasia and the development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79: 321-329. doi:10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80226-4

- Warnakulasuriya S. Oral precancer - a review. In: Varma AK, ed. Oral Oncology. McMillan; 1993;93-96.

- Silverman S Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. a follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53(3):563-568. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f

- Humphris GM, Field EA. An oral cancer information leaflet for smokers in primary care: results from two randomised controlled trials. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(2):143-149. doi:10.1111/j.0301-5661.2004.00129.x

- Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(10):575-580. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x

- van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):423-425. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.016

- Scheifele C, Reichart PA. Oral leukoplakia in manifest squamous epithelial carcinoma: a clinical prospective study of 101 patients. Orale Leukoplakien bei manifestem Plattenepithelkarzinom: Eine klinisch-prospektive Studie an 101 Patienten. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1998;2(6):326-330. doi:10.1007/s100060050081

- Haya-Fernández MC, Bagán JV, Murillo-Cortés J, Poveda-Roda R, Calabuig C. The prevalence of oral leukoplakia in 138 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2004;10(6):346-348. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01031.x

- Hogewind WF, van der Waal I, van der Kwast WA, Snow GB. The association of white lesions with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study of 212 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18(3):163-164. doi:10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80117-1

- Schepman K, der Meij E, Smeele L, der Waal I. Concomitant leukoplakia in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 1999;5(3):206-209. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00302.x

- Petti S. Pooled estimate of world leukoplakia prevalence: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(8):770-780. doi:10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00102-7

- Liu W, Wang YF, Zhou HW, Shi P, Zhou ZT and Tang GY. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia: a retrospective cohort study of 218 Chinese patients. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:685. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-685

- Shah JP, Johnson NW, Batsakis JG, eds. Textbook of Oral Cancer. 1st ed. Martin Dunitz;2003: 4.

- Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48(11):3282-3287.

- Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(1A):187-200. doi:10.1079/phn2003588

- Petersen PE. Oral cancer prevention and control--the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4-5):454-460. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.023

- Boundouki G, Humphris G, Field A. Knowledge of oral cancer, distress and screening intentions: longer term effects of a patient information leaflet. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(1):71-77. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00118-6

- Motallebnejad MM, Khanian M, Alizadeh R, Dabbaghian I. Community survey of knowledge about oral cancer in Babol: effect of an education intervention. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(6):1489-1495.

- Sánchez Beiza L, Martín-Carrillo Domínguez P, Gil Serrano P, Gómez Gil E, Pascual de la Torre M, Valero Martínez A. Preliminary study of smoking cessation at 6 months following medical counseling, pamphlet, and follow-up. Estudio preliminar del abandono del tabaco a los 6 meses tras consejo médico, folleto y seguimiento Aten Primaria. 1992;10(4):738-741.

- Williams M, Bethea J. Patient awareness of oral cancer health advice in a dental access centre: a mixed methods study. Br Dent J. 2011;210(6):E9. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.201

- Singh K, Sharma D, Kaur M, Gauba K, Thakur JS, Kumar R. Effect of health education on awareness about oral cancer and oral self-examination. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:27. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_82_15

- Shibly O, Cummings KM, Zambon JJ. Resolution of oral lesions after tobacco cessation. J Periodontol. 2008;79(9):1797-1801. doi:10.1902/jop.2008.070544