Rare Primary ALK-Positive Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma of the Central Nervous System

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a rapidly growing and aggressive hematological malignancy. This case highlights the rarity of isolated intradural extramedullary manifestations in the pediatric population.

Abstract

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rapidly growing and aggressive hematological malignancy. We present the case of a 12-year-old adolescent boy with a 2-week history of left iliac fossa and presacral pain radiating to the lower limbs associated with emesis and constipation. Subsequently, the patient developed poorly controlled hypertension and progressive lower limb weakness. Imaging revealed an intradural extramedullary mass at the L1 level, and pathology reported large, atypical cells consistent with ALK-positive ALCL. This case highlights the rarity of isolated intradural extramedullary manifestations in the pediatric population.

Keywords: Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma; human central nervous system neoplasms; pediatric oncology; intradural neoplasms; treatment outcome; ALK protein, human.

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare and aggressive hematological malignancy classified under non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is characterized by CD30 antigen activation and belongs to the spectrum of lymphoproliferative disorders. ALCL is further subclassified based on ALK expression into ALK-positive or ALK-negative subtypes, with the former predominant in pediatric cases.1

ALCL accounts for 10% to 15% of pediatric lymphomas and typically involves lymph nodes with extranodal involvement, most commonly in peripheral, mediastinal, or abdominal regions. These lymphomas often present as painless masses and may exhibit B symptoms, particularly in advanced-stage disease.1 In children, clinical presentations may include respiratory distress or superior vena cava syndrome caused by mediastinal compression. Rarely, ALCL may manifest as a primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, accounting for less than 5% of cases, particularly in pediatric patients.2

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and physical examination, with confirmation through histopathological and immunophenotypic criteria, including CD30 and ALK expression, usually via lymph node biopsy. Patients with ALK-positive subtypes have a 5-year survival rate of 70% to 80%, significantly better than the ALK-negative subtype, making early diagnosis crucial for effective management.3,4

This case report aims to underscore the importance of considering primary CNS lymphomas as a potential cause of intradural masses. It also highlights successful oncological management based on the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munich ALCL-99 protocol (Table5) and the incidental finding of a pelvic ectopic kidney, initially misinterpreted as tumor extension on imaging.

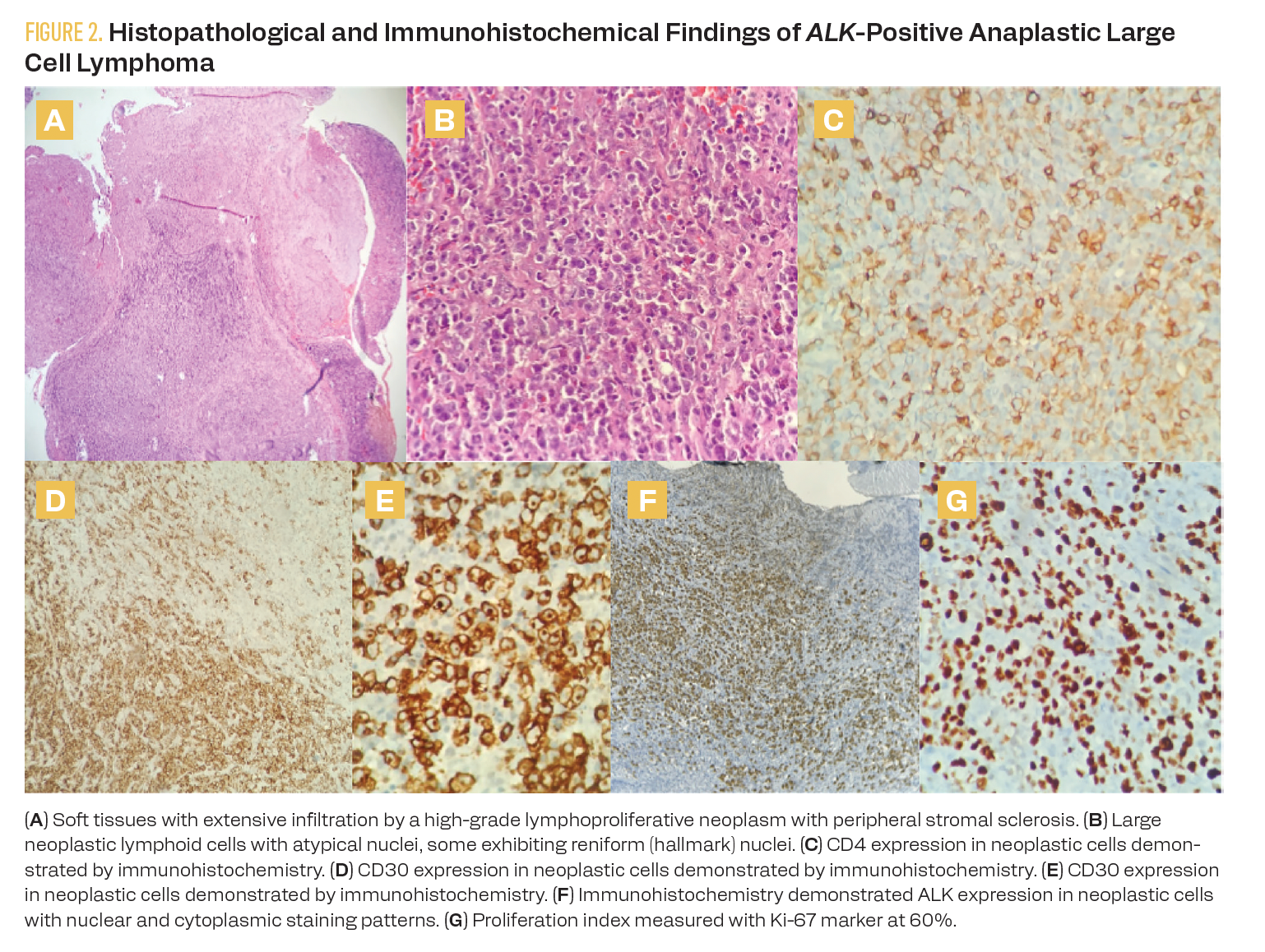

TABLE. Summary of Treatment Based on the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munich ALCL-99 Cooperative Group Strategy5

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy presented with a 2-week history of left iliac fossa and presacral pain radiating to the lower limbs, primarily the thighs and knees, accompanied by episodes of emesis with food. Initial consultations provided symptomatic treatment. Despite this, the patient experienced persistent symptoms, including constipation and hypertension, the latter becoming increasingly difficult to manage. The pain in his extremities worsened, prompting referral to our institution.

The patient required intensive care monitoring for hypertensive emergencies managed with nitroprusside infusion. Physical examination revealed acute onset decreased strength (2/5) and hyperreflexia in the right lower limb, and sphincter function was preserved.

Diagnosis

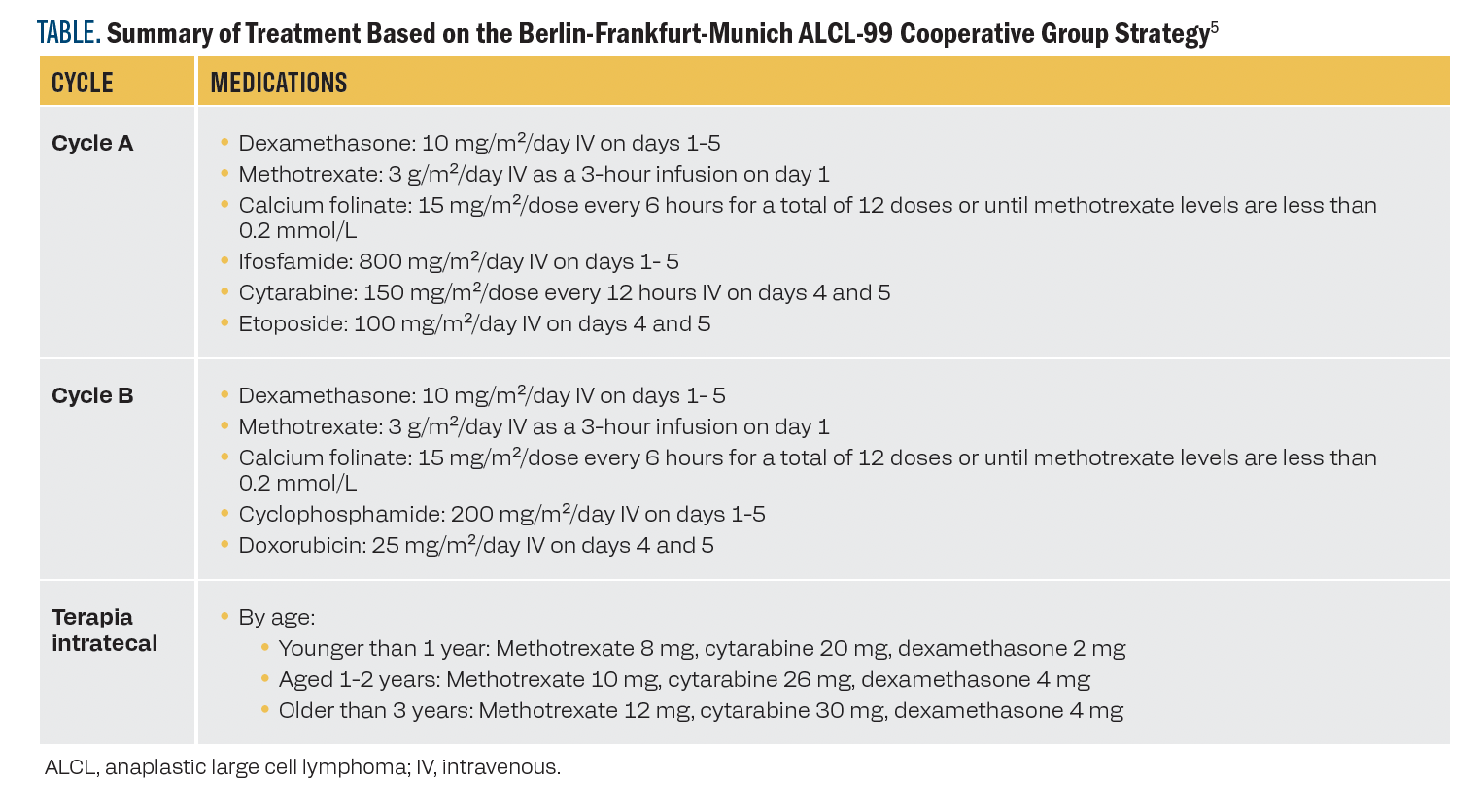

A contrast-enhanced lumbar spine MRI showed an intradural, extramedullary mass at the L1 level with intense solid enhancement, well-defined margins, and no evidence of infiltration into adjacent structures. The mass measured approximately 3.8 × 1.3 × 1.5 cm in longitudinal, anteroposterior, and transverse axes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Initial Contrast-Enhanced Thoracolumbar Spine MRI

Assessment

A laminectomy and resection of the intradural extramedullary lesion were performed, achieving complete macroscopic resection. Postoperative imaging showed no residual tumor. Extension studies with brain and spine MRI revealed no evidence of distant metastatic lesions.

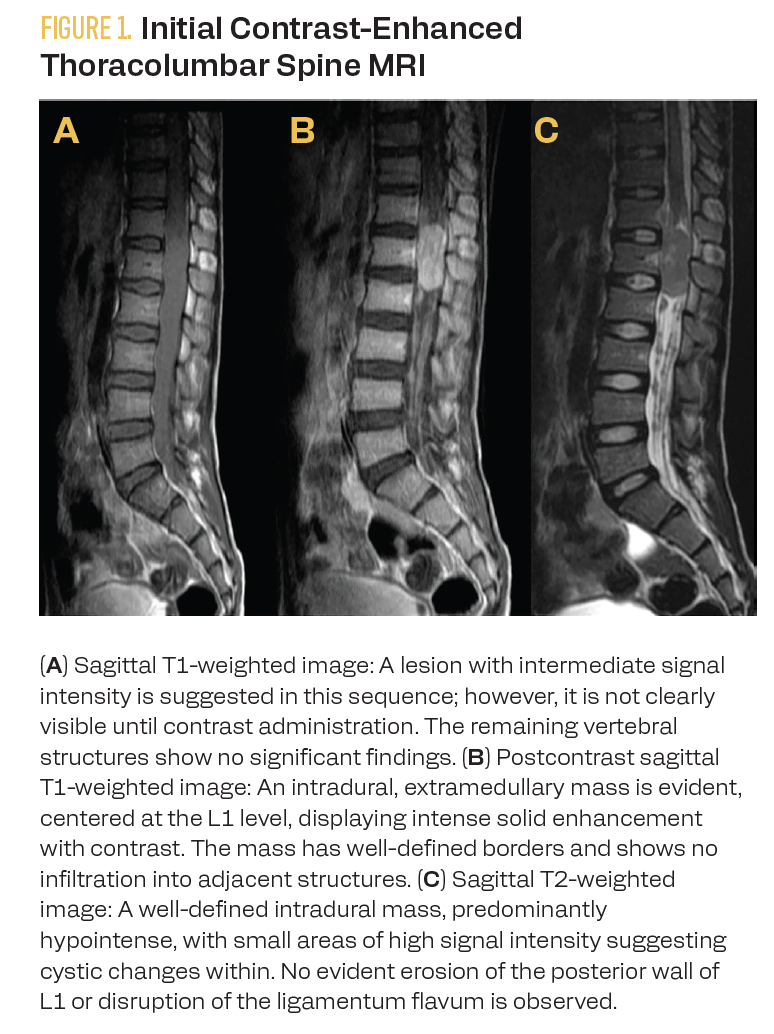

Tumor pathology demonstrated soft tissue infiltration by large, atypical cells with irregular nuclear membranes, partially condensed chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and moderate cytoplasm. Some cells exhibited kidney-shaped nuclei (hallmark cells) and were arranged in nodular aggregates associated with stromal sclerosis and capsular thickening. The tumor microenvironment included a heterogeneous population of reactive lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and histiocytes.

Immunohistochemical studies revealed positivity of neoplastic cells for CD30, CD4, CD3 (focal), CD5 (focal), CD7 (focal), CD8 (focal), granzyme B (focal), and GATA-3 (40% of neoplastic cells), as well as ALK-1 with a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 60% to 70%. Markers CD20, Pax5, CD15, CD56, LPM1, and SOX10 were negative. The histopathological findings and immune profile are consistent with ALK-positive ALCL (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings of ALK-Positive Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Results of laboratory extension studies revealed no significant cytopenias on the diagnostic complete blood count, with leukocytes at 10,300/µL, neutrophils at 6610/µL, lymphocytes at 2460/µL, monocytes at 850/µL, hemoglobin at 12.2 g/dL, and platelets at 522,000/µL. Lactate dehydrogenase was 150 U/L. Renal and hepatic function and electrolyte levels were within normal limits. Bone marrow aspiration biopsy showed trilineage hematopoiesis, and cerebrospinal fluid cytology revealed no tumoral cells.

Patient Treatment and Disease Management

Oncological treatment following the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munich ALCL-99 protocol for ALCL was initiated. The patient was noted to have stage IV disease because of central nervous system involvement, given the initial presentation with an intradural extramedullary mass in the lumbosacral spine. As part of the oncological management, intrathecal therapy was administered along with high-dose systemic methotrexate. The patient was stratified into the high-risk group.

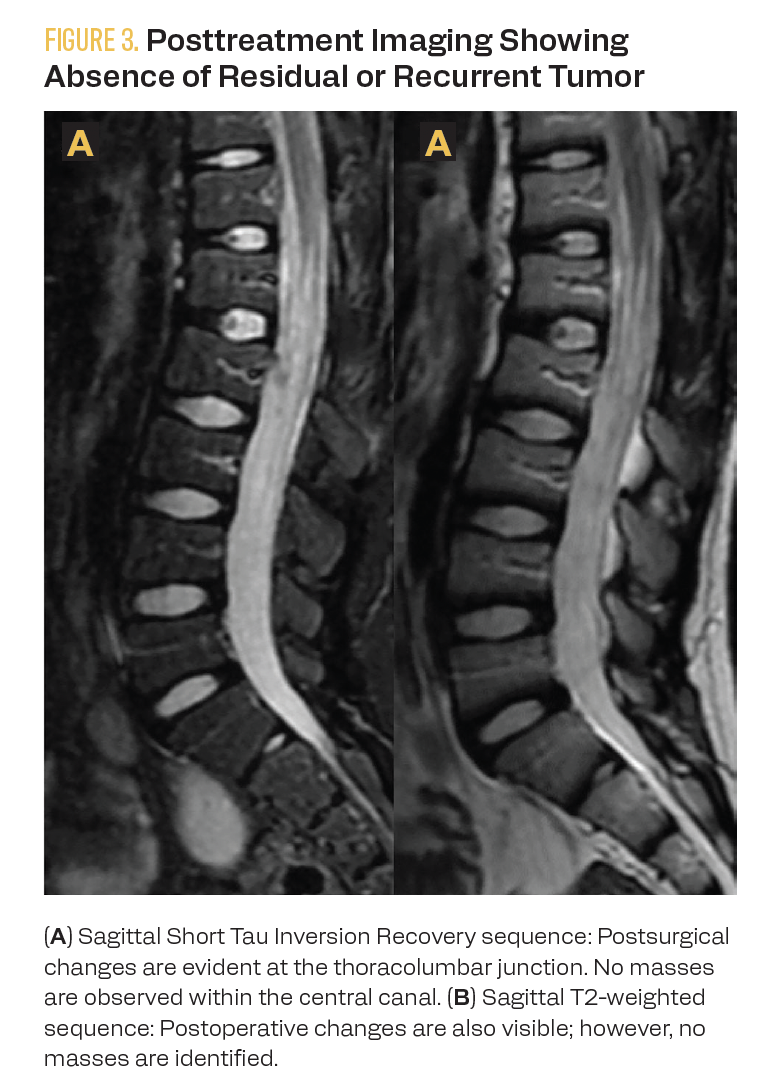

A staging PET-CT with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was performed at diagnosis and for end-of-treatment evaluation. Initially, the functional imaging reported a nodal conglomerate in the pelvic region and the absence of the left kidney. However, renal scintigraphy revealed the abnormal location of the right kidney in the pelvic region, ruling out abdominal nodal tumor involvement. End-of-treatment FDG PET-CT showed no evidence of hypermetabolic lesions suggesting lymphoproliferative tumor involvement. Anatomical imaging with MRI at the end of treatment showed no evidence of tumor recurrence (Figure 3). Eighteen months after diagnosis, the patient is undergoing follow-up care, with no evidence of tumor recurrence or relapse.

FIGURE 3. Posttreatment Imaging Showing Absence of Residual or Recurrent Tumor

Discussion of Outcomes

In pediatrics, ALCL typically presents with systemic symptoms and, in more advanced stages, B symptoms, including unexplained fever, unintentional weight loss, and excessive sweating. Respiratory distress may also occur. However, the clinical presentation of an intradural extramedullary mass in the thoracolumbar region, as demonstrated in this case, is uncommon. In the literature, the most frequent presentations of primary CNS lymphomas are tentorial or supratentorial, whereas spinal involvement is extremely rare, particularly in pediatric patients, making this presentation unique. Although ALCL is more common inadolescents, with a predominance of the ALK-positive subtype, primary CNS manifestations are extremely rare, accounting for approximately 5% of cases.6

ALCL typically involves nodal or extranodal regions, often affecting mediastinal or peripheral areas but very rarely the CNS. The absence of nodal or systemic involvement in this patient highlights the case’s uniqueness, as most ALCLs have significant nodal involvement.6 Previous studies have described that initial manifestations in children with ALCL include respiratory symptoms or complications related to mediastinal compression, such as superior vena cava syndrome or respiratory distress. In contrast, this patient presented with pelvic and presacral pain radiating to the lower limbs and poorly controlled hypertension, which is atypical for the classical presentation of this lymphoma. This constellation of symptoms, combined with the location of the mass, initially led to more common differential diagnoses, such as infectious processes or benign spinal tumors, emphasizing the challenges of early diagnosis.7,8

The patient’s oncological management followed the Berlin-

Frankfurt-Munich ALCL-99 cooperative group protocol, which includes high-dose systemic methotrexate and intrathecal chemotherapy. This protocol has shown favorable outcomes in cases of anaplastic lymphoma with CNS involvement. Eighteen months of posttreatment follow-up revealed complete remission without evidence of tumor recurrence, highlighting the success of this

protocol-based management.9

Additionally, the incidental finding of a pelvic ectopic kidney initially misinterpreted as a nodal conglomerate in the initial evaluation underscores the importance of meticulous imaging evaluation to avoid diagnostic errors that could affect treatment and prognosis.

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of considering primary CNS lymphomas as a possible etiology in pediatric patients presenting with intradural masses, even without nodal or systemic involvement. The combination of an unusual clinical presentation and oncology management based on standardized protocols allowed for complete remission of the disease in this patient. A review of the literature reveals that this type of presentation is extremely rare, making this case a valuable contribution to the existing knowledge of ALCL.10

Corresponding author

Edgar Fabián Manrique Hernández, MD.

Calle 155A No. 23 - 58, Floridablanca, Santander.

Phone: +57 3209560967

Email: fabianmh1993@gmail.com

References

- Turner SD, Lamant L, Kenner L, Brugières L. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma in paediatric and young adult patients. Br J Haematol. 2016;173(4):560-572. doi:10.1111/bjh.13958

- Khoubila N, Sraidi S, Madani A, Tazi I. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in children: state of the art in 2023. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2024;46(5):217-224. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000002475

- Dearden CE, Johnson R, Pettengell R, et al. Guidelines for the management of mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms (excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphoma). Br J Haematol. 2011;153(4):451-485. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08651.x

- Escobosa Sánchez OM, Herrero Hernández A, Acha García T. Endobronchial anaplastic large cell lymphoma in childhood. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;70(5):449-452. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2008.12.008

- Wrobel G, Mauguen A, Rosolen A, Reiter A, Williams D, Horibe K, et al. Safety assessment of intensive induction therapy in childhood anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Report of the ALCL99 randomised trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(6):1071-7.

- Ahrendsen JT, Ta R, Li J, et al. Primary central nervous system anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK positive. Am J Clin Pathol. 2022;158(2):300-310. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqac046

- Eichler AF, Batchelor TT. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21(5):E15. doi:10.3171/foc.2006.21.5.16

- Sahoo D, Gupta AK, Wajid MA, Meena JP, Seth R. Clinical presentation and outcomes of pediatric anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a tertiary center experience from India. Indian J Cancer. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.4103/ijc.IJC_368_20

- Spiegel A, Paillard C, Ducassou S, et al. Pediatric anaplastic large cell lymphoma with leukemic presentation in children: a report of nine French cases. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(4):545-551. doi:10.1111/bjh.12777

- Kim DH, Ko YH, Lee MH, Ree HJ. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting as an endobronchial polypoid mass. Respiration. 1998;65(2):156-158. doi:10.1159/000029248

Highlighting Insights From the Marginal Zone Lymphoma Workshop

Clinicians outline the significance of the MZL Workshop, where a gathering of international experts in the field discussed updates in the disease state.