Synovial Fluid in Checkpoint Inhibitor–Induced Inflammatory Arthritis

This case report and literature review emphasize that ICI-IA should not be ruled out based on the presence of synovial fluid with elevated WBC with a neutrophil predominance. Early steroid use should be considered.

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are increasingly used in the treatment of advanced malignancies, but they can cause a wide range of adverse effects, including inflammatory arthritis. Severe ICI-induced inflammatory arthritis (ICI-IA) is rare, and its distinguishing clinical features are not defined. We present a patient with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who developed severe, polyarticular inflammatory arthritis while being treated with an ICI. Arthrocentesis of native and prosthetic joints revealed a significantly elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with a neutrophil predominance. Antibiotics were discontinued when the extensive infectious workup remained negative, and the patient was diagnosed with ICI-IA. This presentation of ICI-IA had overlapping features with septic arthritis, resulting in high diagnostic uncertainty. We comprehensively reviewed all published literature on the clinical features of severe ICI-IA. In the literature, synovial fluid findings revealed variable WBC counts but consistently have a neutrophil predominance. Although severe cases are rare, 9 previously reported cases shared similarities, including polyarticular presentation, elevated inflammatory markers, and absence of other rheumatic disease. Severe ICI-IA appears to have significant clinical overlap with culture-negative septic arthritis. This case report and literature review emphasize that ICI-IA should not be ruled out based on the presence of synovial fluid with elevated WBC with a neutrophil predominance. Early steroid use should be considered.

Keywords: checkpoint inhibitor, inflammatory arthritis, immune-related adverse effects

Introduction

In the past decade, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have significantly impacted the treatment of patients with advanced malignancies by targeting innate immune system checkpoints, including CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1.1 ICIs are currently approved for a variety of advanced malignancy indications, including urothelial cancers. Although these agents have proven highly effective in harnessing the immune system to target malignancies, they often cause a wide range of immune-related adverse events (irAEs).2,3 These irAEs have been reported to affect nearly every organ system.2 The presentation of toxicity is often nonspecific, leading to high diagnostic and management uncertainty.

Among the various clinical manifestations of irAEs, rheumatic or musculoskeletal AEs are sometimes considered less severe or more tolerable. Musculoskeletal irAEs are inconsistently reported in clinical trials but are estimated to affect anywhere from 1% to 43% of patients and often occur in the first 3 months of therapy.4-6 Reported phenotypes range from mild arthralgia to systemic disease with debilitating arthritis. ICI-IA is thought to be the most common phenotype, followed by polymyalgia rheumatica and myositis, respectively.5,7,8 The ICI-induced inflammatory arthritis (ICI-IA) phenotype is variable and nonspecific, often closely mimicking rheumatoid arthritis (RA) due to its polyarticular nature.9 However, compared with RA, ICI-IA is nearly exclusively found to have negative autoantibodies.5 Different immunotherapy drug targets may partly explain variability in presentation.8

The common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) grades ICI-IA in increasing severity from grade 1 to 3.10 Grade 3 is defined as “severe pain associated with signs of inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling; irreversible joint damage; limiting self-care activities of daily living.” There are limited data on the incidence of each CTCAE grade of arthritis in the current body of literature. A 2021 systematic review of all inflammatory arthritis irAEs found the CTCAE grade was documented in less than one-third of cases. Of those documented, less than 15% were grade 3, encompassing fewer than 20 patients.11 Furthermore, the synovial fluid has not been further characterized.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old man with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who was on anti–PD-1 immunotherapy presented with fever and severe bilateral shoulder, knee, and ankle pain. Medical history was significant for stage IV chronic kidney disease, hypertension, bilateral hip and knee replacements, and peripheral neuropathy. He had a 50-pack-year smoking history. Seven years prior to presentation, he underwent radical cystoprostatectomy for treatment of high-grade urothelial carcinoma in situ. He had no evidence of recurrent disease until 2 years prior to the current presentation when he was hospitalized for urosepsis requiring nephrostomy tubes; renal cytology was remarkable for high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. The patient subsequently underwent a nephrectomy with negative margins, but restaging scans 3 months later revealed progressive metastatic disease.

The patient completed 4 cycles of palliative carboplatin/gemcitabine with a partial response before starting immunotherapy with pembrolizumab. The second dose of pembrolizumab was delayed by 1 week for mild elevation of liver enzymes, which self-resolved. After 3 months on pembrolizumab, the patient reported mild arthralgia of the wrists and shoulders that was partially attributed to a fall and stabilized with conservative pain management. However, after 8 months of pembrolizumab, arthralgia of the wrist, shoulders, and hips returned with increasing severity, and the patient was started on 10 mg of prednisone daily with a presumed diagnosis of grade 1 ICI-IA. Symptoms improved with prednisone, and pembrolizumab was continued. After 10 months of therapy, pembrolizumab was held for 1 week when the patient developed severe diarrhea requiring hospitalization. There was initial concern for treatment-related AE, but diarrhea resolved with conservative management and ultimately was diagnosed as infectious diarrhea when colonic biopsies were normal.

Four days later, the patient again presented to the hospital for fever of acute onset (38.3 °C) and severe bilateral shoulder, knee, and ankle pain. Physical exam was remarkable for mildly erythematous knees

and ankles without significant edema. Further workup revealed:

- White blood cell (WBC) count of 15.1 × 103 cells/µL

(predominantly neutrophilic) - Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 18 mm/h

- C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/dL

- Normal lactic acid

- Knee x-ray:

- Small to moderate bilateral effusions

- Unremarkable hardware

- Left-sided ossified bodies

Based on systemic symptoms and joint findings and concern about possible septic arthritis, orthopedic surgery and infectious disease were consulted. The orthopedic surgery team performed multiple arthrocentesis, which revealed significantly elevated WBC counts of 47,000 cells/µL (91% polymorphonuclear leukocyte count [PMN]) in the right ankle, 97,000 cells/µL (100% PMN) in the left prosthetic knee, and 70,000 cells/µL (98% PMN) in the right prosthetic knee, all with initial negative crystal analysis, Gram stain, and culture. Given the neutrophilic predominance of synovial fluid, septic arthritis was favored over possible ICI-IA. The patient proceeded to surgery for irrigation and debridement of the bilateral knee and ankle joints. Additionally, bilateral knee arthroplasties were explanted, and antibiotic spacers were placed.

Despite the intraoperative presence of purulent effusion in all joints except the left ankle, cultures remained negative. Based on the purulent nature of effusion and accompanying neutrophilic predominance, the patient was initiated on antibiotics. With negative Gram stain (cultures pending), treatment for ICI-IA was also initiated with prednisone at 1 mg/kg. The patient was ultimately discharged with antibiotics and steroids.

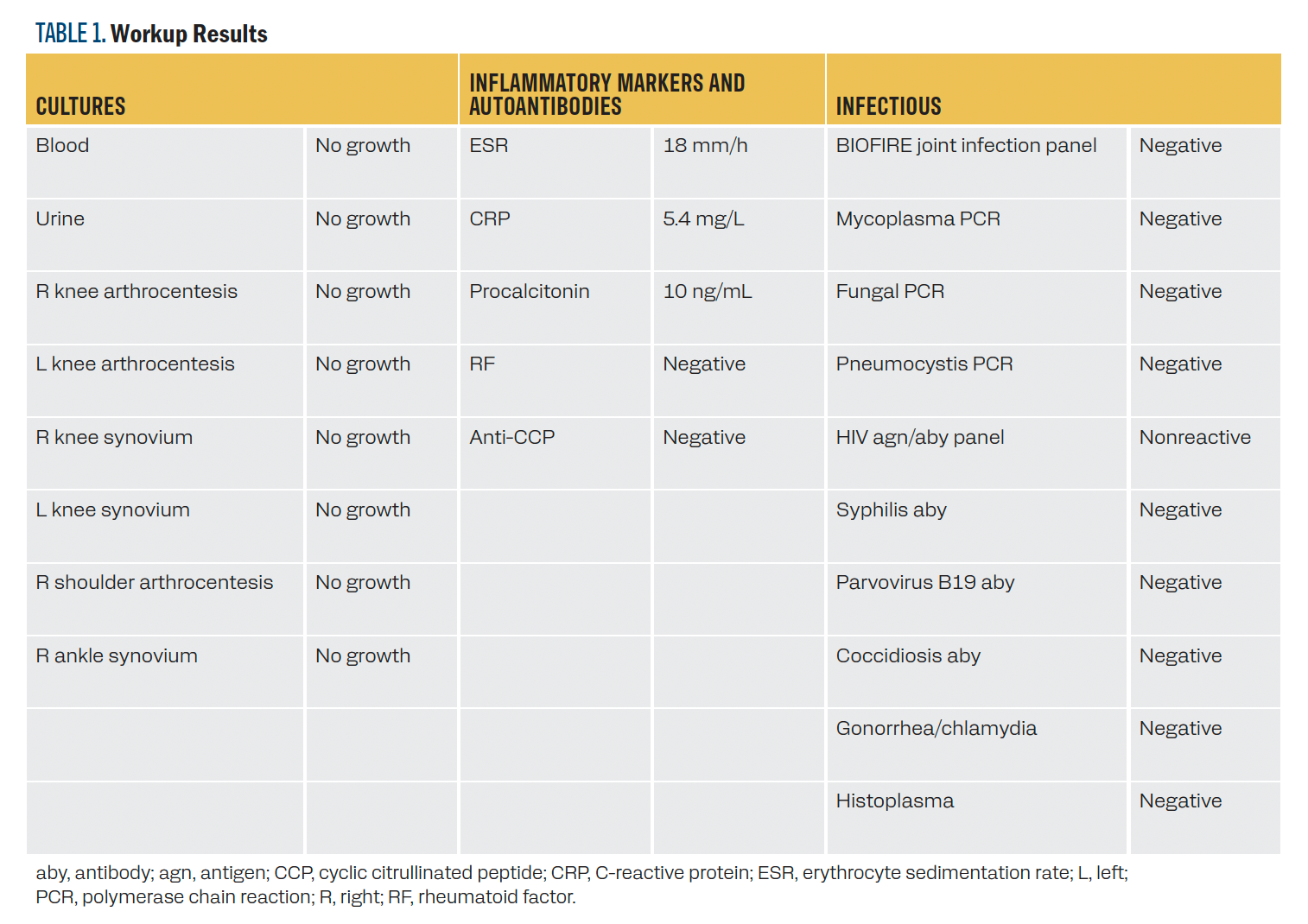

Three weeks after discharge, the patient was seen by the infectious disease team, who noted that the patient’s symptoms had rapidly and vastly improved. In the setting of a broadly negative infectious workup (Table 1), antibiotics were discontinued, and the improvement was attributed to steroids. The patient was diagnosed with grade 3 ICI-IA and continues to follow with rheumatology. He underwent a prolonged steroid taper lasting approximately 1 year and has not required disease-modifying agents for arthritis to date. Pembrolizumab therapy was permanently discontinued.

TABLE 1. Workup Results

Discussion

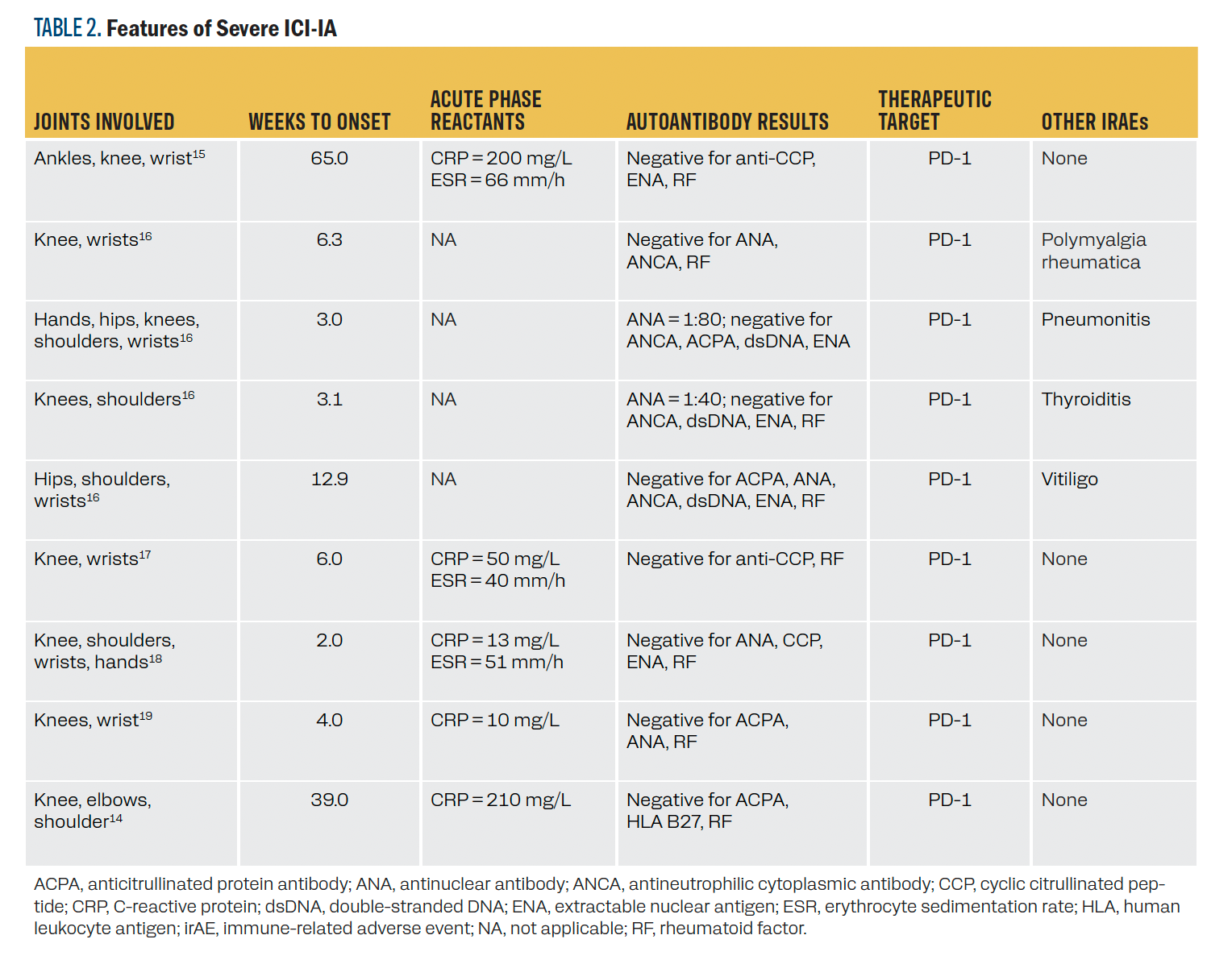

We reviewed the literature for characteristics of previous cases

of CTCAE grade 3 ICI-IA. We identified 9 patients with noted

grade 3 ICI-IA with individual case characteristics reported

(Table 2). We identified 2 additional studies with mention of grade 3 ICI-IA, but the characteristics of the patients were not individually noted.12,13 All 9 patients were treated with anti–PD-1 therapy and had reported polyarticular arthritis. When reported, all cases had elevated inflammatory markers with negative

antibody testing, except for 2 patients with mildly elevated

antinuclear antibodies. Four patients had previous irAEs prior

to ICI-IA diagnosis. Time to onset was quite variable, ranging from 2 to 65 weeks.

TABLE 2. Features of Severe ICI-IA

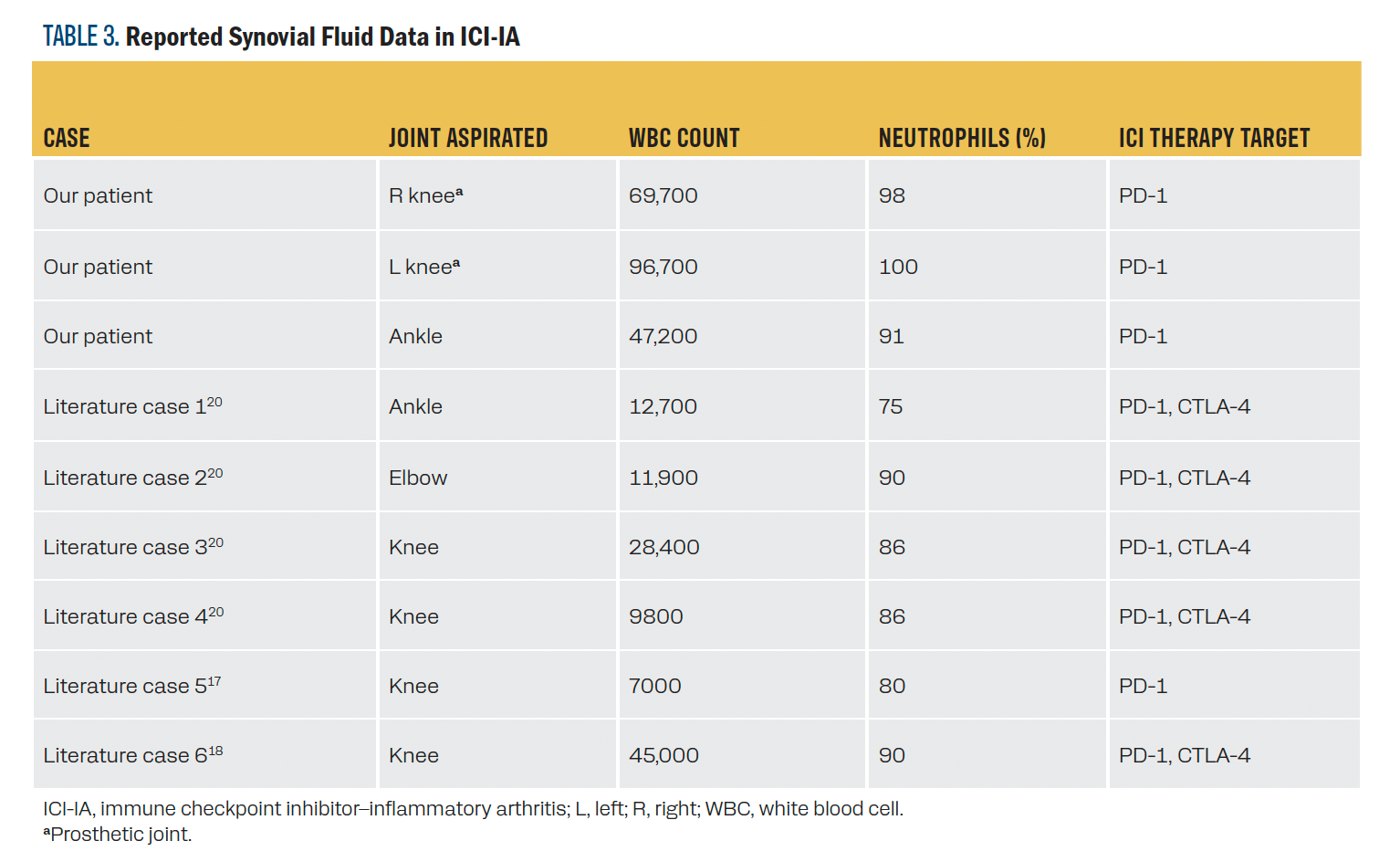

Given the impact of synovial fluid findings in managing our patient’s case, we also reviewed the literature for any previously reported synovial fluid data in ICI-IA of any grade. We identified 6 published cases of ICI-IA with synovial fluid data (Table 314-19). We identified an additional case with synovial fluid data, but the patient was already on high-dose prednisone, so the case is excluded here.14 WBC count varied widely but consistently had a strong predominance of neutrophils. Most samples were taken from the knee. All but 1 of the previously reported cases were treated with a combination of PD-1 and CTLA-4 therapeutic targets.

TABLE 3. Reported Synovial Fluid Data in ICI-IA

Conclusion

We present a case of polyarticular ICI-IA complicated by the presence of prosthetic joints and high diagnostic uncertainty. The significantly elevated WBC count with a neutrophil predominance in the synovial fluid of prosthetic joints resulted in a very high index of suspicion for infection, followed by subsequent explanation and revision of bilateral prosthetic knee joints. We attempted to review the literature for musculoskeletal irAEs in patients with prosthetic joints. To our knowledge, ICI-IA in those with nonnative joints has not been previously reported. Indications for ICI use continue to increase, and the occurrence of cancers with ICI therapeutic indication has significant overlap with the ages of the population most likely to have prosthetic joints. Understanding how ICI therapy impacts nonnative joints should be an area of future study, given the increasing use of ICI in our aging population.

Synovial fluid data heavily influenced the management of this patient’s case. In the limited literature available, at the very least, neutrophilic predominance does not exclude ICI-IA. In our case and those reported previously, there is no single finding to rule in or rule out ICI-IA, highlighting the importance of consideration of the entire clinical picture. Polyarticular, seronegative arthritis may support ICI-IA; however, not treating septic arthritis likely has devastating consequences. This patient eventually was cotreated for infection and ICI-IA. The decision to discontinue antibiotics and attribute the patient’s symptom improvement to high-dose steroids is a significant aspect of this patient’s management. Antibiotics were discontinued only after all data were available weeks later to make the ICI arthritis diagnosis. In cases such as this, where preliminary infectious workup is negative and the clinical picture could be suggestive of an irAE, the judicious use of steroids can be crucial in managing the patient’s symptoms and addressing the underlying autoimmune component. In the future, multidisciplinary guidelines may be developed to differentiate these presentations and decrease morbidity and mortality.

This case highlights the complexity of diagnosing and managing joint-related symptoms in a patient receiving immunotherapy, where both infectious and immune-related etiologies need to be considered and appropriately addressed. It also highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach involving various medical specialties.

There were multiple limitations to this literature review. Cases of severe ICI-IA are rare, and distinguishing characteristics are not yet well defined. Although synovial fluid findings differ between septic native and nonnative joints, these distinctions are not well characterized in the few published reports of ICI-IA synovial fluid. ICIs have dramatically impacted survival in a growing number of advanced malignancies, but thorough attention must be given to further understanding their impact on the immune system and how they factor into the decision tree for patients with potential irAEs.

Corresponding Author

Mary Katherine L. Anderson, MD

982055 Nebraska Medical Center

Omaha, NE 68198-2055

Telephone: 402-559-8500

Fax: 402-559-6520

Email: mk.anderson@unmc.edu

References

- Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Lou Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and beyond. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):45. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01056-8

- Webb ES, Liu P, Baleeiro R, Lemoine NR, Yuan M, Wang YH. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Biomed Res. 2018;32(5):317-326. doi:10.7555/JBR.31.20160168

- Williams SG, Mollaeian A, Katz JD, Gupta S. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis: identification and management. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(8):771-785. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2020.1804362

- Cappelli LC, Gutierrez AK, Bingham CO 3rd, Shah AA. Rheumatic and musculoskeletal immune-related adverse events due to immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(11):1751-1763. doi:10.1002/acr.23177

- Angelopoulou F, Bogdanos D, Dimitroulas T, Sakkas L, Daoussis D. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal manifestations. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(1):33-42. doi:10.1007/s00296-020-04665-7

- Zhang S, Zhou Z, Wang L, Li M, Zhang F, Zeng X. Rheumatic immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors compared with placebo in oncologic patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:2040622320976996. doi:10.1177/2040622320976996

- Roberts J, Ennis D, Hudson M, et al. Rheumatic immune-related adverse events associated with cancer immunotherapy: a nationwide multi-center cohort. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(8):102595. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102595

- Cappelli LC, Brahmer JR, Forde PM, et al. Clinical presentation of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis differs by immunotherapy regimen. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48(3):553-557. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.02.011

- Chan KK, Bass AR. Monitoring and management of the patient with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis: current perspectives. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:3105-3118. doi:10.2147/JIR.S282600

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version5. Published: November 27. US Department of Health and HumanServices, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute

- Ghosh N, Tiongson MD, Stewart C, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor-associated arthritis: a systematic review of case reports and case series. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27(8):e317-e322. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000001370

- Diehl A, Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee E, Grossman SA. Relationships between lymphocyte counts and treatment-related toxicities and clinical responses in patients with solid tumors treated with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2017;8(69):114268-114280. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23217

- Bashey A, Medina B, Corringham S, et al. CTLA4 blockade with ipilimumab to treat relapse of malignancy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113(7):1581-1588. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-168468

- Murray-Brown W, Wilsdon TD, Weedon H, et al. Nivolumab-induced synovitis is characterized by florid T cell infiltration and rapid resolution with synovial biopsy-guided therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000281. doi:10.1136/jitc-2019-000281

- Chan MMK, Kefford RF, Carlino M, Clements A, Manolios N. Arthritis and tenosynovitis associated with the anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab in metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2015;38(1):37-39. doi:10.1097/CJI.0000000000000060

- Mitchell EL, Lau PKH, Khoo C, et al. Rheumatic immune-related adverse events secondary to anti-programmed death-1 antibodies and preliminary analysis on the impact of corticosteroids on anti-tumour response: a case series. Eur J Cancer. 2018;105:88-102. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.027

- Spathas N, Economopoulou P, Cheila M, et al. Inflammatory arthritis induced by pembrolizumab in a patient with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2018;8:409. doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00409

- Subedi A, Williams SG, Yao L, et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to identify immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e200032. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0032

- Lauwyck J, Schreuer M, Meric de Bellefon L, Van Erps J, Neyns B, Aspeslagh S. Severe treatment-induced inflammatory polyarthritis in advanced melanoma patients: 2 case reports. Melanoma Res. 2022;32(3):200-204. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000814

- Cappelli LC, Gutierrez AK, Baer AN, et al. Inflammatory arthritis and sicca syndrome induced by nivolumab and ipilimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):43-50. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209595