Recurrent Small Cell Carcinoma of the Lung With Cutaneous Metastasis in Breast

Experts present a case of recurrent small cell lung cancer presenting with a cutaneous metastatic nodule in the right breast.

Dr Allen received his doctorate of medicine from the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, where he also completed his residency in diagnostic radiology and fellowship in interventional radiology. He is certified in diagnostic radiology by the American Board of Radiology.

Dr Copur is a medical oncologist/ hematologist at Morrison Cancer Center, Mary Lanning Healthcare in Hastings, Nebraska, and is a professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska. He is also an editor-at-large and a Community Oncology Advisory Board member at ONCOLOGY®.

Dr Horn is a pathologist at Mary Lanning Healthcare in Hastings, Nebraska.

Carlene R. Springer is a nurse practioner at Mary Lanning Cancer Center in Hastings, Nebraska.

Dr Zusag is a radiation oncologist at Mary Lanning Cancer Center in Hastings, Nebraska.

Figure 1. Breast nodule before chemotherapy

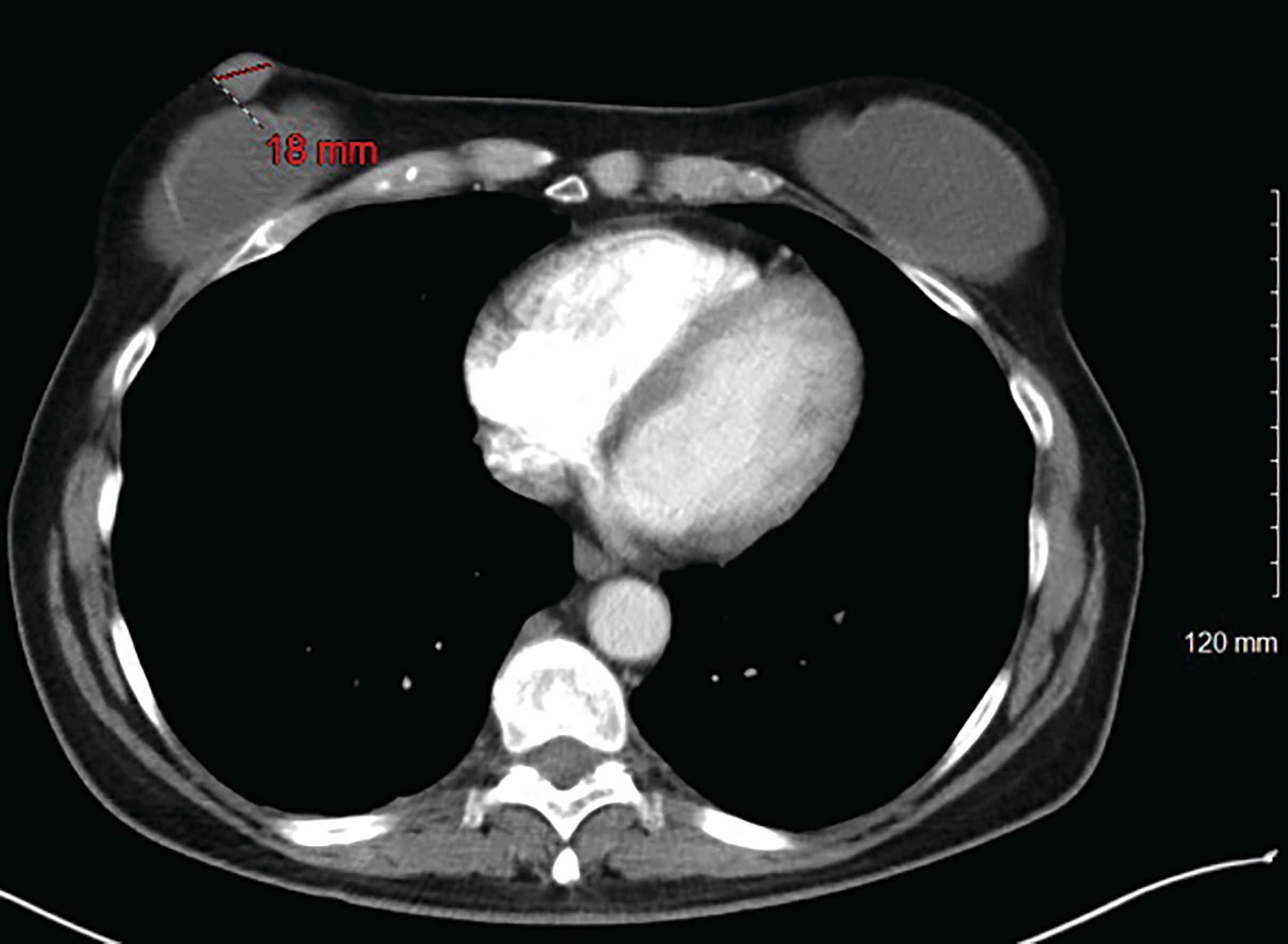

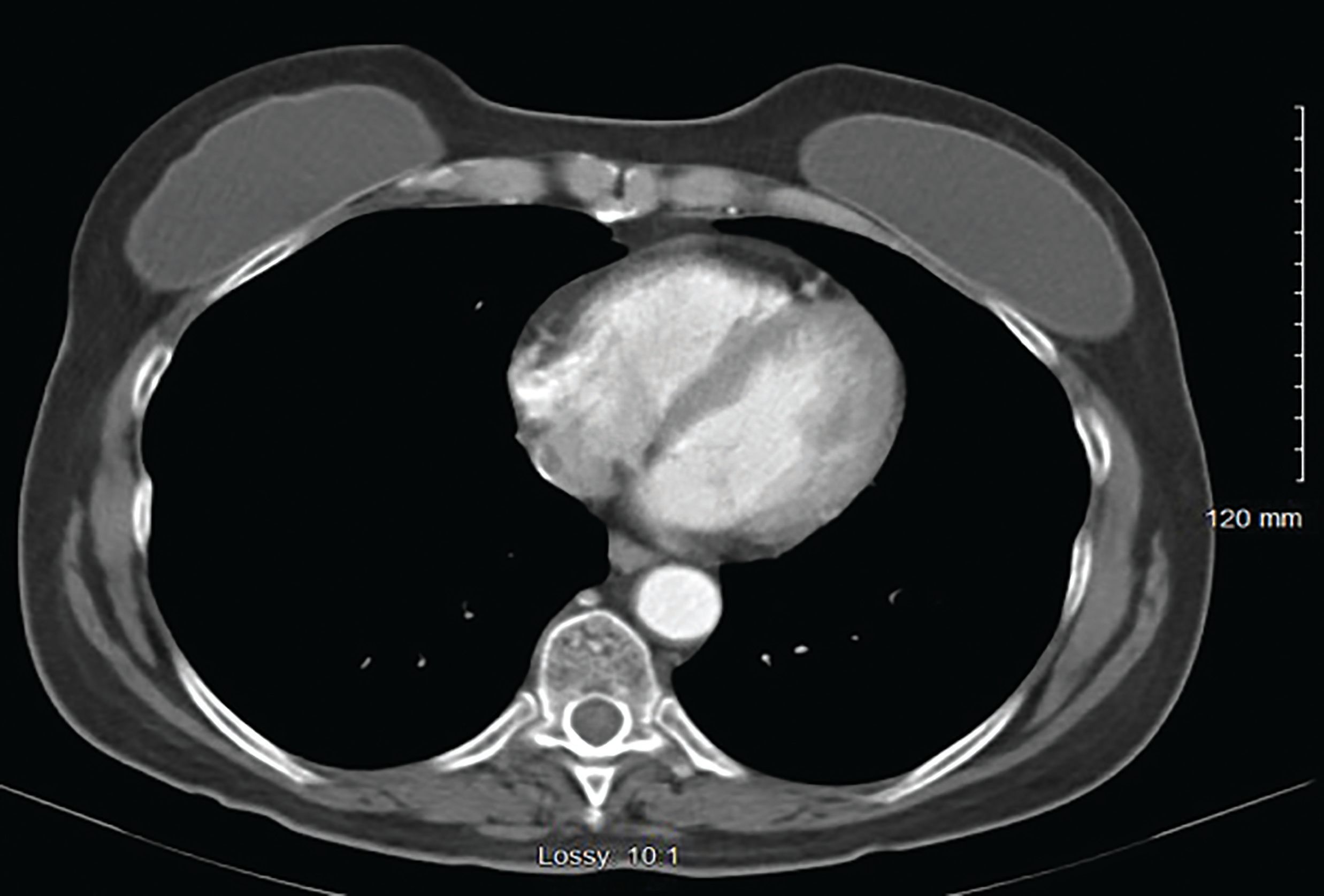

Figure 2. CT Image of breast nodule before chemotherapy

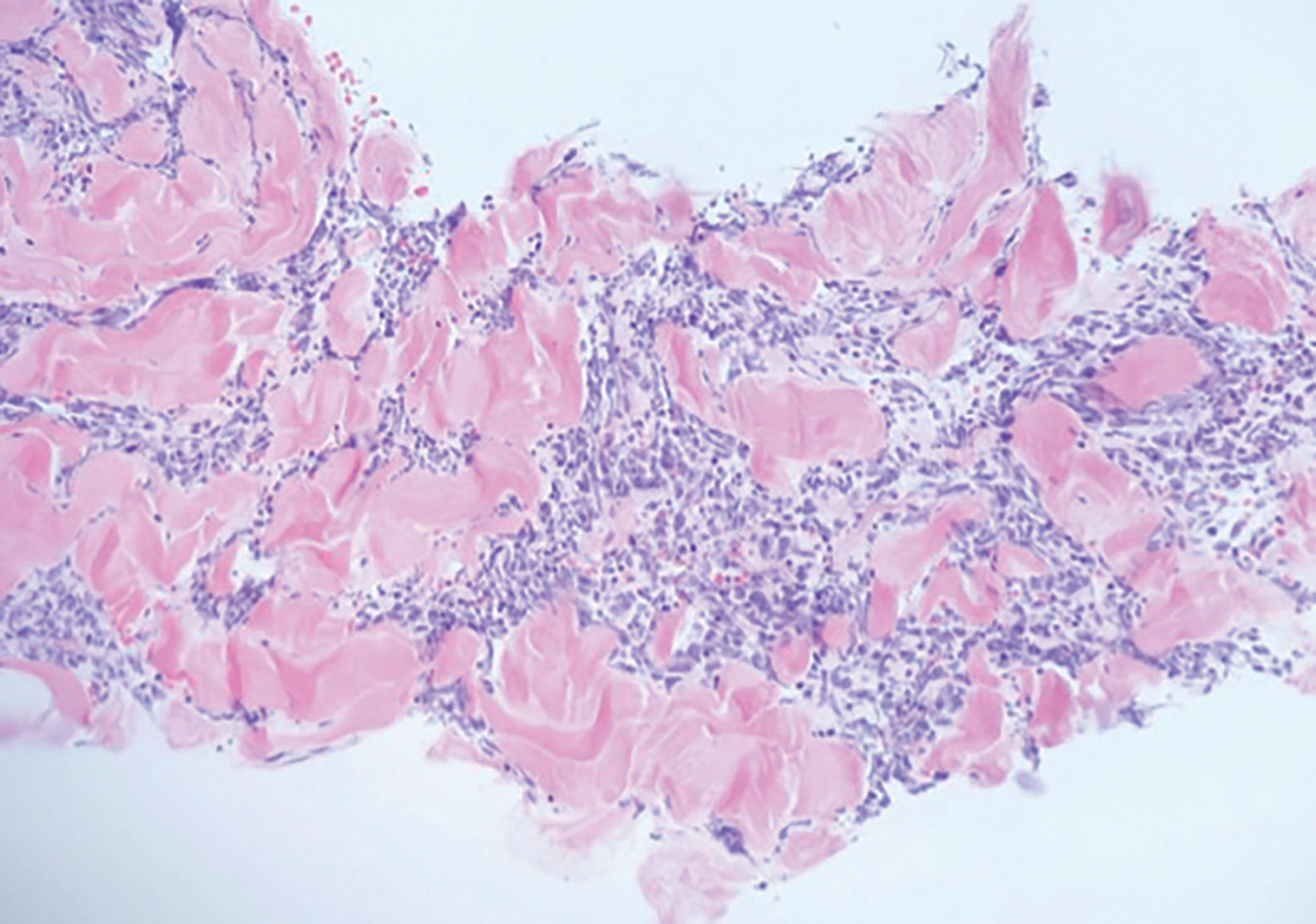

Figure 3. H&E stain showing malignant cells with scant cytoplasm and nuclear molding

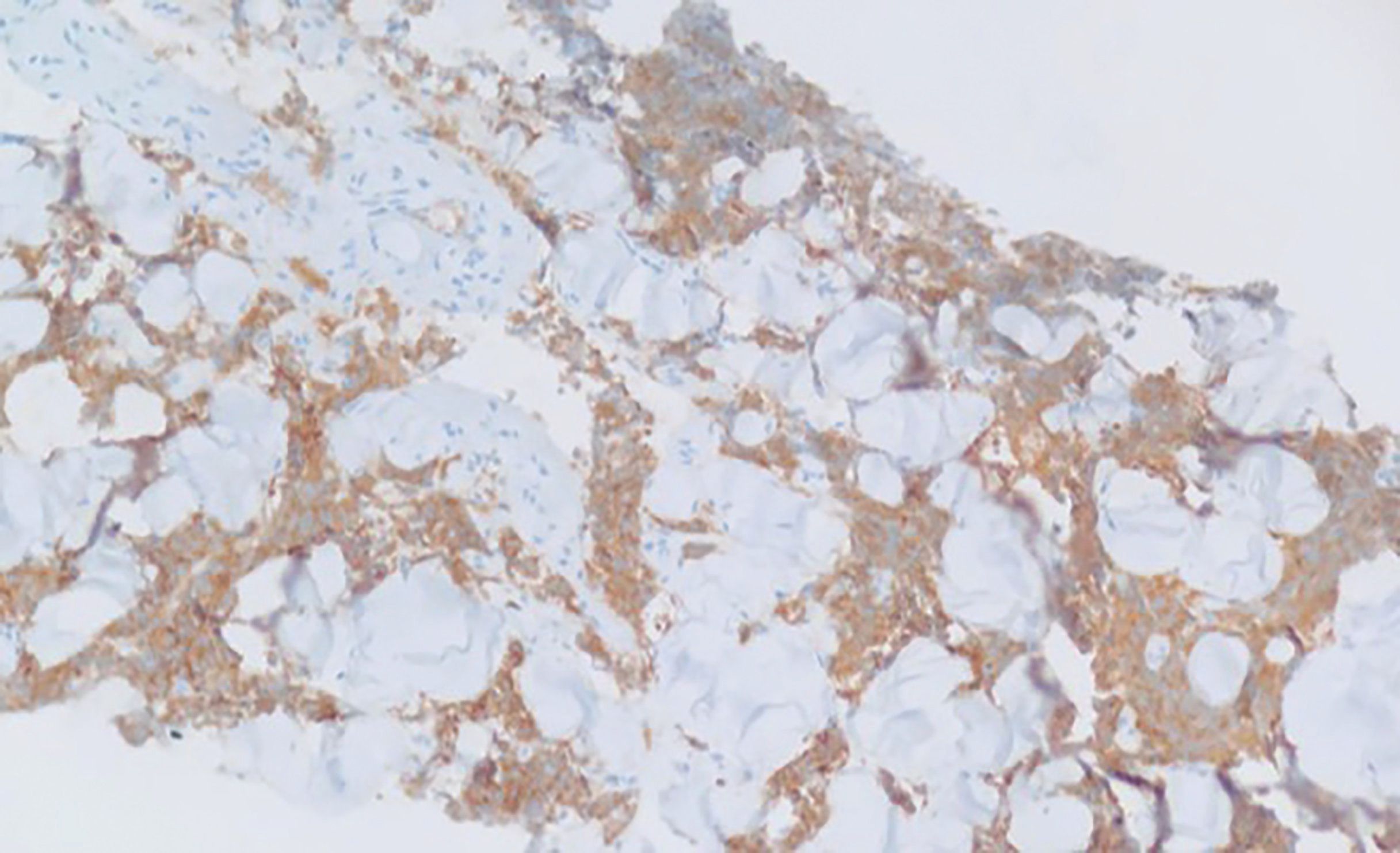

Figure 4. Malignant cells positive immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin

Figure 5. Breast nodule after chemotherapy

Figure 6. CT image of breast nodule after chemotherapy

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths and the second leading cause of new cancer cases in the United States. Although more commonly involving hilar nodes, the liver, adrenal glands, bones, and the brain, lung cancer can metastasize to almost any organ. Metastases, although rare in the skin may be the first sign of a lung cancer or cutaneous metastases may present as a sign of recurrent disease. The incidence of cutaneous metastases from lung cancer has been reported in approximately 1% to 12 % of cases and was associated with poor prognosis. Although cutaneous metastasis from small cell lung cancer is a rare occurrence, cutaneous metastasis involving the breast is even less common. Here, we present a case of recurrent small cell lung cancer presenting with a firm purplish cutaneous metastatic nodule in the right breast.

Background

Internal malignancies leading to metastases in the skin are rare with a reported incidence of 2% in 5 large autopsy studies.1 Cutaneous metastasis occurs when cells from a cancer in the body spread to the skin through the lymphatic system or bloodstream, or the cancer cells may spread directly to the skin through a surgical scar. Cutaneous metastases can occur after the primary cancer has been diagnosed, or in some cases, these lesions may be the first presenting sign of the cancer. Lung cancer is likely responsible for the majority of cutaneous metastases in men and is the second leading cause of cutaneous metastases in women after breast cancer.2 The most commonly reported metastatic skin lesions originate from primary breast, lung, and colon cancers. Other cancers that have the potential for cutaneous metastasis include melanoma, and those of the kidney, oral cavity, cervix, ovaries, and pancreas. Cutaneous metastases from kidney and oral cavity cancers are more often seen in men and appear on the head and neck regions. Skin findings include fast-growing, firm, mobile, painless pink or purple lesions that may ulcerate.

Breast cancer is the most common form of cutaneous metastasis in women because of its high prevalence rate. Lung cancer is the most common primary malignancy to metastasize to the skin in men. The incidence of cutaneous metastases from lung cancer varies between 1% to 12% of cases.3 All histological types of lung cancer may cause metastases in the skin. Metastases from lung cancer may be the first sign of lung cancer and clinically it cannot be distinguished from cutaneous metastases originating from other organs.4 The most common sites of cutaneous metastases from lung cancer are the chest, abdomen, head, and neck.4,5 Clinically, cutaneous metastases occur as round or oval nodules, mobile or fixed, firm, and usually skin-colored (sometimes red, dark red, purple, or black). The nodules are usually painless and sometimes can be ulcerated. They can infrequently appear in the form of solitary or grouped papules, plaque-like, zosteriform, erysipelas-like, or as cicatricial alopecia on the scalp.6-8 When lesions present on the chest, they may have spread directly from a lung biopsy site. Some lesions of cutaneous lung cancer metastases have been found to run parallel to the blood vessels of the rib cage. Although all different histologic subtypes of lung cancer have been linked to the development of cutaneous metastases, adenocarcinoma or large cell carcinoma of the lung are more frequently reported to metastasize in this fashion.9-11 The second most common primary source of metastatic skin disease involving both sexes is colorectal carcinoma. The abdomen and pelvis are the most common locations for these cutaneous metastases to appear. A Sister Mary Joseph node at the umbilicus is a hallmark sign of an underlying gastrointestinal cancer.12,13

Case

A 57-year-old white woman presented with a subcutaneous, purplish, 1.8-cm nodule in the lower middle of her right breast (Figure 1). Past medical history was significant for bilateral silicone breast implants 10 years ago, and a diagnosis of limited-stage small cell lung cancer treated with etoposide/cisplatin plus concurrent chest wall radiation which led to complete remission 1 year ago. In evaluation of this skin nodule, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the breast nodule was performed. The CT scan of the chest confirmed the presence of bilateral breast implants with a 1.8-cm breast nodule in the middle lower quadrant of the right breast, and a right axillary lymph node (Figure 2). Pathology of tissue from the breast nodule biopsy are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Further work-up with CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis revealed adenopathy in the abdomen adjacent to aorta and left adrenal gland. She was started on second-line chemotherapy with paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin (area under the concentration time curve of 6) given intravenously every 3 weeks. After 4 cycles of chemotherapy, the breast nodule was no longer visible or palpable on physical exam (Figure 5). Restaging CT scans showed resolution of the breast nodule and axillary and abdominal lymphadenopathy (Figures 6).

Discussion

Cancer metastasis is an organ-selective process determined by anatomical, biological, and specific microenvironmental factors.14 The exact mechanism of lung cancer metastasis to the skin is not clearly understood. Several recent studies have suggested that unique genes and gene signatures might be involved.15,16 Lung and breast carcinomas are the most common primary tumors that lead to cutaneous metastases in the skin in men and women, respectively. A number of cancers demonstrate colonization preference to their regions of origin-lung cancer to the supradiaphragmatic skin and colorectal cancer to the infradiaphragmatic skin regions. Although any histological type of lung cancer is capable of cutaneous metastasis,17 adenocarcinomas and large cell carcinomas are the most frequently reported histology in the literature.2,3

Small cell carcinoma of the lung seldom metastasizes to the skin.18,19 In a review of 4020 cases of cutaneous metastases from systemic cancers, 19 were of pulmonary origin and only 2 arose from small cell carcinoma.20 The malignant cells of small cell carcinoma often affect regional areas via lymphatic channels, but they can also disseminate widely throughout the entire body via hematogenous spread. Metastases in the skin occur when the disease has progressed and they indicate poor prognosis.4,21 Survival time after the appearance of cutaneous metastases can be as short as 5 to 6 months.22 Patients who present with cutaneous metastases earlier during the disease course have poorer prognosis compared with those who develop skin metastases later in the disease course.23

Metastatic lesions are often found on the anterior chest, head, scalp, back, and abdomen, and less commonly on the shoulders, flank, and upper and lower extremities.17,20 Metastases to the breast from extramammary sites are very unusual and account for 0.4% to 2.0% of breast malignancies.22 They may present as solitary or multiple lesions with ulcerative or exudative features. Cutaneous manifestations of small cell carcinoma are variable and do not have classic pathognomonic features. Several general characteristics that have been described include nodular, mobile, fast growing, and painless. On biopsy, specimens may appear to remain superficial, or they may invade the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.11 In the differential diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of small cell lung cancer to the breast, primary small cell carcinoma of the breast should be excluded. Primary small cell carcinoma of the breast is a very rare entity with fewer than 30 cases reported in the English-language literature.24 The histological findings of primary small cell carcinoma of the breast and of other organs are similar, although their immunohistochemistry staining characteristics are different. The histological detection of in situ intraductal components is important in making the diagnosis of primary small cell carcinoma of the breast along with the immunohistochemical staining for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 , thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, chromogranin, and synaptophysin.25 Although primary small cell lung cancer is usually TTF-1-positive, this finding is nonspecific.26 It can be positive in small cell carcinoma of many primary sites, and determining the primary organ requires clinical and radiographic correlation. The histologic and immunophenotypic findings of our case were typical for small cell carcinoma, showing cells with fine chromatin, minimal cytoplasm, and nuclear molding. No associated intraductal component was present (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin (Figure 4). CK20 was negative, excluding Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusions

In the advanced stage, small cell lung cancer most frequently metastases to the liver, but it can also go to the other organs. Cutaneous metastases may be the first sign or they can develop as a recurrence of previously treated disease (as it was in our case). Due to their nonspecific appearance, these skin lesions can be overlooked or misdiagnosed as benign lesions or as second primary tumors. In our case, the unusual location of this single isolated breast metastasis suggested several differential diagnostic possibilities, including silicone implant-related granuloma, angiosarcoma of the breast, primary small cell carcinoma of the breast, or Merkel cell carcinoma. The presence of cutaneous metastases signifies an advanced-stage disease and carries a poor prognosis. Clinicians should keep this uncommon but important presentation in mind and evaluate suspicious skin lesions appropriately.

Outcome of the Case

The patient had a complete clinical response to second-line chemotherapy. Her disease is being monitored closely and at the first sign of recurrence, she will be treated with ipilimumab plus nivolumab combination immunotherapy.27

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no significant financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

- Coslett LM, Katlic MR. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1990;97(3):â757-759. doi:10.1378/chest.97.3.757.

- Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29(5):1298-1307. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197205)29:5<1298::aid-cncr2820290526>3.0.co;2-6.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35(6):459-462. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.35.459.

- Dreizen S, Dhingra HM, Chiuten DF, Umsawasdi T, Valdivieso M. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases of lung cancer. Clinical characteristics. Postgrad Med. 1986;80(8):111-116. doi:10.1080/00325481.1986.11699635.

- Neel V, Sober A. Metastatic tumors to the skin. In: Kufe D, Bast R, Frei E, Holland J, Gansler T, Pollock R, Weichselbaum R, eds. Cancer Medicine. Danbury, CT: B. C. Decker Incorporated; 2003.

- Ahmed I. Cutaneous Metastases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Horn T, Mancini A, Mascaro J, Rapini R, Salasche S, Saurat J, Stingl G, eds. Dermatology. Spain: Mosby; 2003:1953-1956.

- Homler HJ, Goetz CS, Weisenburger DD. Lymphangitic cutaneous metastases from lung cancer mimicking cellulitis. Carcinoma erysipeloides. West J Med. 1986;144(5):610-612.

- Kikuchi Y, Matsuyama A, Nomura K. Zosteriform metastatic skin cancer: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2001;202(4):336-338. doi:10.1159/000051670.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol.1995;33(2 Pt 1):161-182. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90231-7.

- Triller Vadnal K, Triller N, Požek I, Kecelj P, Košnik M. Skin metastases of lung cancer. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17(3):125-128.

- Kamble R, Kumar L, Kochupillai V, Sharma A, Sandhoo MS, Mohanti BK. Cutaneous metastases of lung cancer. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(842):741-743. doi:10.1136/pgmj.71.842.741.

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, Borghese M. Umbilical metastasis: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3(1):13. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-3-13.

- Salemis NS. Umbilical metastasis or Sister Mary Joseph’s Nodule as a very early sign of an occult cecal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2007;38(2-4):131-134. doi:10.1007/s12029-008-9024-0.

- Kovács KA, Hegedus B, Kenessey I, Timár J. Tumor type-specific and skin region-selective metastasis of human cancers: another example of the “seed and soil” hypothesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32(3-4):493-499. doi:10.1007/s10555-013-9418-8.

- Kall SL, Koblinski JE. Genes That Mediate Metastasis Organotropism. In: Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. Austin (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2000-2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK154549/.

- Wan L, Pantel K, Kang Y. Tumor metastasis: moving new biological insights into the clinic. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1450-1464. doi:10.1038/nm.3391.

- Ambrogi V, Nofroni I, Tonini G, Mineo TC. Skin metastasis in lung cancer: analysis of a 10-year experience. Oncol Rep. 2001;8(1):57-61.

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106(5):1448-1450. doi:10.1378/chest.106.5.1448.

- De Argila D, Bureo JC, Márquez FL, Pimentel JJ. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung presenting as a cutaneous metastasis of the lip mimicking a Merkel cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24(3):170-172. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1999.00445.x.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF: Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 Pt 1):228-236. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70173-q.

- Estarriol MH, Goday MR. Images in clinical medicine. Cutaneous metastases of small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2583. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm031071.

- Mollet TW, Garcia CA, Koester G. Skin metastases from lung cancer. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(5):1.

- Liu W, Palma-Diaz F, Alasio TM. Primary small cell carcinoma of the lung initially presenting as a breast mass: a fine-needle aspiration diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(3):208-212. doi:10.1002/dc.20995.

- Ussavarungsi K, Kim M, Tijani L. Skin metastasis in a patient with small-cell lung cancer. The Southwest Respiratory and Critical Care Chronicles. 2013;1:35-38.

- Kitakata H, Yasumoto K, Sudo Y, Minato H, Takahashi Y. A case of primary small cell carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer. 2007;14(4):414-419. doi:10.2325/jbcs.14.414.

- Altintoprak F, Baytekin HF, Tasdemir C. Primary small cell carcinoma of the lung presenting with breast and skin metastases. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(2):207-209. doi:10.3904/kjim.2011.26.2.207.

- Antonia SJ, López-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):883-895. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30098-5.