CLL14 Trial: Fixed-Duration Chemotherapy-Free Regimen for Frail Patients with Treatment-Naïve CLL

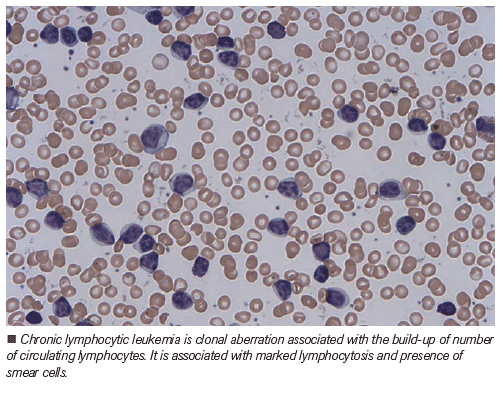

The treatment landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia has dramatically changed in the past decade.

Dr. Fakhri is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Blood and Marrow Transplantation, at the University of California, San Francisco, California.

Dr. Andreadis is a Professor of Clinical Medicine in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Blood and Marrow Transplantation, at the University of California, San Francisco, California.

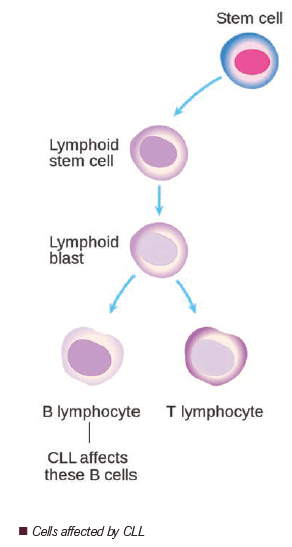

The treatment landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has dramatically changed in the past decade. Ibrutinib, a once-daily oral Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, has proved to significantly improve outcomes for patients with CLL. The phase 3 RESONATE trial, which compared the single-agent ibrutinib to the anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab in 391 high-risk, multiply relapsed/refractory patients with CLL (rrCLL) led to the approval of ibrutinib in the United States and Europe.[1] In the frontline setting, the RESONATE-2 study compared ibrutinib to chlorambucil in 269 patients age 65 years or older. Ibrutinib consistently demonstrated significant improvements in survival outcomes for patients in all subgroups, including those considered at high risk.[2–4] The extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial indicated a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 70% versus 12%, favoring the ibrutinib arm.[4]

Given the outstanding results of the RESONATE-2 trial, more recent trials have investigated ibrutinib-based combinations in the frontline setting. The Alliance Data and Safety Monitoring Board evaluated the efficacy of ibrutinib, either alone or in combination with rituximab, compared to chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in 547 patients age 65 years or older with untreated CLL. Their results indicated superior PFS in patients randomized to ibrutinib-based arms compared to BR. There was no significant difference between ibrutinib and ibrutinib plus rituximab with regard to PFS.[5] In a similar fashion for the younger patient population, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)-American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) Cancer Research Group (E1912) compared treatment with ibrutinib–rituximab to chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in 529 patients age 70 years or younger with treatment-naïve CLL. The ECOG-ACRIN study of the ibrutinib–rituximab regimen resulted in improved PFS compared to FCR.[6] Based on the robust data from these two landmark trials, the field of CLL has undergone a paradigm shift, abandoning traditional chemoimmunotherapy options for novel targeted agents.

Outside clinical trials, the majority of patients with CLL are older than age 70 years and have multiple coexisting medical conditions. Such patients require effective treatment options with acceptable side-effect profiles. The CLL11 trial established chlorambucil–obinutuzumab as a standard of care in this frail patient population.[7] Venetoclax, an inhibitor of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) protein, was initially approved for patients with rrCLL harboring chromosome 17p deletion (deletion 17p) and later approved in combination with rituximab based on results of the phase 3 MURANO trial.[8,9]

The phase 3 CLL14 trial investigated the efficacy of the fixed-duration venetoclax–obinutuzumab combination compared to the previously established regimen of chlorambucil–obinutuzumab in patients with untreated CLL and coexisting conditions.[10] In total, 432 patients from 21 countries with a Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score of greater than 6 (range, 0–56, with higher scores indicative of diminished organ function) or a calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) of less than 70 mL/min were randomly assigned to receive venetoclax–obinutuzumab or chlorambucil–obinutuzumab. Treatment duration in both groups consisted of 12 28-day cycles, and no crossover was allowed. The primary endpoint was PFS. Key secondary endpoints included minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (with a cutoff of 10−4 [< 1 cell in 10,000 leukocytes]) in peripheral blood and bone marrow, overall and complete response rates, and overall survival. In terms of patient characteristics, the median age was 72 years; median CIRS score was 8; and median CrCl was 66 mL/min. In total, 14% of patients had TP53 deletion and/or mutation and 60% had unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) genes. With regard to the risk of tumor lysis syndrome, 13%, 64%, and 22% of patients in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group were at low, medium, and high risk, respectively. A total of 78% of the patients in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group and 75% in the chlorambucil–obinutuzumab group received the planned 12 treatment cycles.

At a median follow-up of 28 months, 30 (14%) primary endpoint events (disease progression or death) were observed in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group compared to 77 (36%) in the chlorambucil–obinutuzumab group (hazard ratio, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.23–0.53; P < .001). The 2-year PFS for the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group was significantly higher compared to the chlorambucil–obinutuzumab group: 88% (95% CI, 84–93) compared with 64% (95% CI, 57–71). This benefit also included the patients with TP53 deletion/mutation in addition to patients with unmutated IGHV. Three months following treatment completion, a higher number of patients in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group had achieved MRD negativity in peripheral blood (76% vs 35%, P < .001) and in bone marrow (57% vs 17%, P < .001). The median overall survival was not reached in either group. The differences in grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, infections, and all-cause mortality were not statistically significant between the two arms.[10] Tumor lysis syndrome was reported in three patients in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group (all cases occurred during treatment with obinutuzumab and before initiation of venetoclax) and in five patients in the chlorambucil–obinutuzumab group. None of these events met the Howard criteria for clinical tumor lysis syndrome. Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 16% of patients in the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group and 15% of patients in the chlorambucil–obinutuzumab group. The superiority in PFS benefit favoring the venetoclax–obinutuzumab group coupled with an acceptable toxicity profile resulted in the approval of venetoclax–obinutuzumab in patients with untreated CLL and multiple comorbidities by the US Food and Drug Administration in May 2019.

Although ibrutinib has been established as a reliable and convenient orally administered agent in the frontline setting for patients with treatment-naïve CLL, the indefinite course of therapy can pose a challenge. In a real-world analysis, intolerance (particularly cardiac dysrhythmias and increased risk of bleeding) was shown to be the main reason for discontinuation.[11] It is also important to be mindful of the “financial toxicities” associated with a recommended “life-long” treatment. In addition, despite high overall response rates with ibrutinib, most responses with continuous treatment are partial, with persistent disease typically in the bone marrow.[12]

Given the aforementioned limitations of ibrutinib, CLL14 is an important trial, offering a time-limited chemotherapy-free regimen capable of achieving high rates of negative MRD in patients with multiple coexisting medical conditions. In terms of limitations, considering the increased risk of tumor lysis syndrome associated with this combination necessitating intense monitoring, its use particularly in the community setting with staffing constraints makes it less convenient than single-agent ibrutinib. In addition, assessment of the long-term follow-up data is precluded given the recent FDA approval of the combination as compared to the 5-year results from the RESONATE-2 trial. It is also important to remember that despite significant advances in the field of CLL, it remains incurable. As such, sequencing of the currently available treatment options in a fashion to provide patients with durable remissions is critical. A phase 2 trial assessed the activity and safety of venetoclax in patients with rrCLL whose disease progressed during or after discontinuation of ibrutinib therapy. An interim analysis of this trial indicated that venetoclax has durable clinical activity and favorable tolerability in this patient population, with an overall response rate of 65% (95% CI, 53–74).[13] Similar studies, however, supporting the activity and safety of ibrutinib following venetoclax failure are not yet available.

With the growing armamentarium of treatment options in the frontline setting for patients with CLL, clinical research should focus on time-limited combination therapies with a favorable toxicity profile that provide patients with durable remissions. It is also critical to delineate optimal therapies in the second line and beyond to maximize clinical benefit from advances in the field. In an effort to address these unmet needs, the Alliance and ECOG groups are currently conducting two important phase 3 clinical trials, each targeting a separate age group. These trials are designed to investigate the efficacy and safety of adding venetoclax to the currently established regimen of obinutuzumab–ibrutinib in the frontline setting for patients older than age 70 years (Alliance; NCT03737981) and those age 18 to 69 years (ECOG; NCT03701282). In addition, the German CLL group has announced the launch of the upcoming CLL17 trial investigating the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib compared with venetoclax–obinutuzumab compared with ibrutinib plus venetoclax. As these trials conclude in the next few years, some of the mysteries around frontline novel agents in CLL will be further deciphered, potentially translating into more positive change for patients with CLL.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Andreadis receives research funding from Pharmacyclics/Johnson & Johnson, and has stock interest and spouse employment with Genentech. Dr. Fakhri has no financial interest in or other relationship with the manufacturer of any product or provider of any service mentioned in this article.

FIVE KEY REFERENCES

1. Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al; RESONATE Investigators. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:213-23.

2. Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, et al. Sustained efficacy and detailed clinical follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: extended phase 3 results from RESONATE-2. Haematologica. 2018;103:1502-10.

4. Tedeschi A, Burger J, Barr PM, et al; Five-year follow-up of patients receiving ibrutinib for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Presented at the 2019 European Hematology Association Annual Congress; June 13-16, 2019; Amsterdam, the Netherlands:abstr S107.

6.Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib–rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:432-43.

10. Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225-36.

References:

1. Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al; RESONATE Investigators. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:213-23.

2. Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, et al. Sustained efficacy and detailed clinical follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: extended phase 3 results from RESONATE-2. Haematologica. 2018;103:1502-10.

3. Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2425-37.

4. Tedeschi A, Burger J, Barr PM, et al; Five-year follow-up of patients receiving ibrutinib for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Presented at the 2019 European Hematology Association Annual Congress; June 13-16, 2019; Amsterdam, the Netherlands:abstr S107.

5. Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2517-28.

6. Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib–rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:432-43.

7. Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1101-10.

8. Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:311-22.

9. Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax–rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1107-20.

10. Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225-36.

11. Mato AR, Nabhan C, Thompson MC, et al. Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica. 2018;103:874-9.

12. O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre S, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131:1910-9.

13. Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:65-75.

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.