Recap: Experts Review Management of Chronic GVHD

Recommendations for treating patients with steroid-refractory chronic GVHD based on evidence demonstrated by the REACH3 trial.

Graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) can be a tricky condition to diagnose and treat. Even as new treatment options and strategies become available, experts in the field say dealing with the disease remains more of an art than a science.

A panel of experts in the treatment of chronic GVHD reviewed some major treatment hurdles and discussed the latest research during a CancerNetwork® Around the Practice presentation, “Updates in the Treatment of Chronic GVHD.” The virtual session was moderated by Parameswaran Hari, MD, MS a professor of medicine and chief of the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Defining Acute vs Chronic GVHD

A diagnosis of GVHD can be difficult to pin down for a number of reasons, said Nelson Chao, MD, MBA, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Cell Therapy in the Department of Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. In addition to simply confirming that the symptoms presenting are in fact the result of GVHD, the lines between the 2 types—acute and chronic—can be blurry.

“It used to be very easy, because 100 days was the break point,” said Chao. “Anything before 100 days was labeled ‘acute,’ and cases after 100 days were labeled ‘chronic.’”

However, as preparatory regimens, prophylaxis, and donor selection have changed, such categories are no longer as meaningful, Chao said. Instead, clinicians should distinguish cases based on how the patient presents.

“The clinical manifestations are very different,” noted Chao. “It’s much more of a hyperacute event with acute GVHD, and an autoimmune-type phenomenon with chronic.”

Joyce Neumann, PhD, APRN, program director of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, said the acute form is typically associated with macular papular erythematous rash and lower gastrointestinal (GI) disease, the most common symptom of which is diarrhea. Upper GI disease, with symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, also can develop, and some patients experience liver involvement.

All of those things—especially skin involvement—can be present in chronic GVHD, Neumann said. “But multiple organs can be involved: the eyes, mouth, and vaginal area in women,” she said. “It is a much more complex kind of phenomenon with chronic GVHD.”

Risk Factors for GVHD

Traditional risk factors for GVHD include a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch between the recipient and the donor, use of female donors for male patients, and the intensity of conditioning regimens.1

Yi-Bin Chen, MD, director of the bone marrow transplant program at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, said that in the CTN-0201 trial (NCT00075816) in which patients were randomized to transplantation with either unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cells or bone marrow, the former led to lower incidence of graft failure but higher rates of chronic GVHD and increased severity.2

“This later translated in long-term follow-up to patients who had received bone marrow being more productive and back to work,” Chen said. “Graft sources have certainly played a role.”

GVHD Prophylaxis

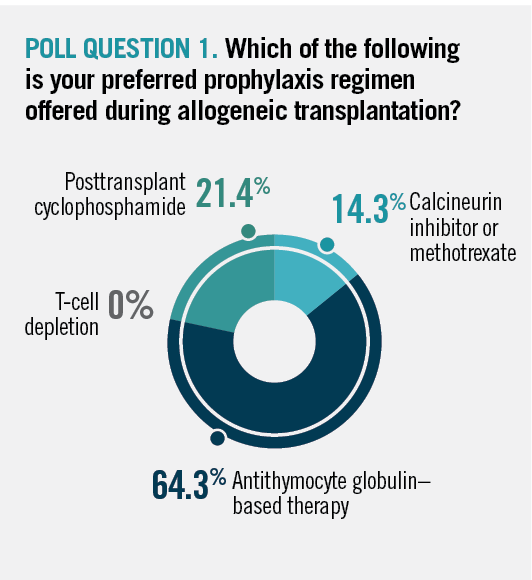

The panel then discussed the issue of prophylaxis, a major component of treatment design, but also an area where options are changing. In an audience poll, most respondents said their preferred prophylaxis regimen for allogeneic transplantation was a calcineurin inhibitor with methotrexate. A distant second choice was posttransplant cyclophosphamide.

Hari said audience poll results regarding GVHD prophylaxis match what he has seen in the transplant community, with calcineurin inhibitors or methotrexate being the most common prophylactic therapy choices, but with posttransplant cyclophosphamide increasingly making an impact as well (Poll question 1).

Poll Question 1. Which of the following is your preferred prophylaxis regimen offered during allogeneic transplantation?

Chao said that in his experience, prophylaxis choices vary from 1 transplant center to another, particularly when it comes to T-cell depletion, an option that none of the viewing audience selected in the poll.

“The bottom line for differences in T-cell depletion and calcineurin inhibitor/methotrexate for the ablative regimens really is picking your poison, in a way,” Chao said. “Do you look for [lower incidence of] GVHD but more relapse, or, perhaps, more GVHD and less relapse?”

Chen said at his center, conventionally matched recipients receive the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus plus methotrexate, whereas recipients of haploidentical or mismatched, unrelated grafts receive posttransplant cyclophosphamide.

“For the nonmalignant patients, who we are seeing an increased number of, we do use a posttransplant cyclophosphamide-based regimen because we do believe that it does prevent chronic GVHD,” noted Chen.

Chen also discussed the potential of antithymocyte globulin prophylaxis, but a difficulty with such regimens is that there are different preparations and formulations, making it difficult to make blanket statements. In Europe, regulators have approved the use of anti–T-lymphocyte globulin (ATLG). However, when he and colleagues studied ATLG,3 they found that it “substantially lowered the incidence of chronic GVHD but it also lowered overall survival from both relapse-related and non–relapse-related causes.”

Chen added that he is excited that prospective randomized trials have gotten underway to help figure out which prophylaxis regimens are superior.

Adverse Effects

Although prophylaxis can lower the risk of GVHD, it also comes with its own risks of adverse events. A 2008 systematic review found a significantly higher incidence of acute renal failure in patients treated with tacrolimus plus methotrexate, despite its superiority over other standard regimens such as cyclosporin/methotrexate in terms of prevention of acute GVHD.4

Neumann said it is important that patients have a clear-eyed view of the pros and cons of their therapy and of the fact that transplantation’s potential benefits may be accompanied by negative impacts.

“It’s really important to let patients know how their quality of life may change—that we may be curing their disease but [that they] may end up with a chronic condition afterward,” which happens in many cases, Neumann said.

Understanding Acute GVHD

Turning to acute GVHD, Chao said that all told, the incidence of acute GVHD is around 40% in his practice, a figure Hari said matches his experience. About half of those end up with steroid-refractory GVHD, which Chen noted can have a significant impact on patient mortality. According to a review on survival in patients with acute GVHD, only about a quarter of patients with grade III and just 1% to 2% of patients with grade IV will survive past 2 years.5

Still, the panelists said it can be difficult to accurately grade acute GVHD. Chen said the MAGIC Consortium in 2016 put out consensus guidelines that have helped clear up some of the gray areas.6

One of the newer developments in stratifying patients, Chen said, is the use of plasma biomarkers, specifically, ST2 and REG3α. He said commercially available tests allow clinicians to get a prognostic score, although he emphasized that the biomarkers are not diagnostic; rather, they are measures of inflammation and organ injury. “That is thought to give us a biological signal of how aggressive [a patient’s] acute GVHD is,” he said.

Chen also said that measuring biomarkers 1 week posttransplant can help put patients into risk groups for acute GVHD. However, he cautioned that while biomarkers are already

being used, clinical trials have not definitively proven their efficacy.

Acute GVHD in a Patient

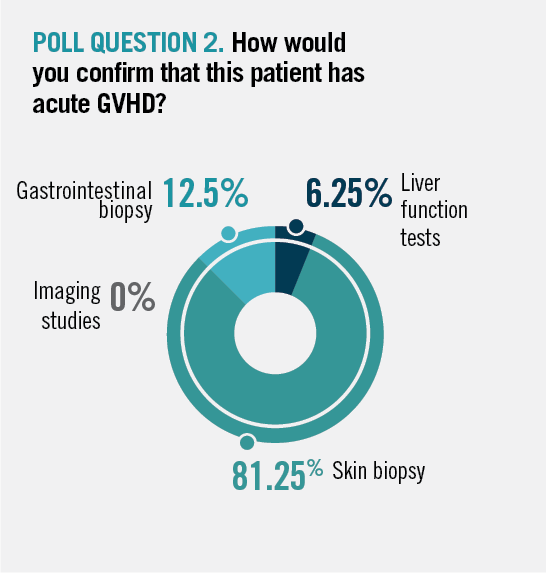

Neumann said the significant skin involvement in the patient described plus the number of stools per day suggest that the patient has a case of stage I acute GVHD. In such a situation, she suggested doing a skin biopsy to confirm acute GVHD.

“Certainly a GI biopsy can also be done, but that might be after we get some cultures or check for other reasons why the patient may have diarrhea, such as C. difficile,” Neumann said. In a poll, audience members agreed with her, with most opting for a skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis (Poll question 2).

Poll Question 2. How would you confirm that this patient has acute GVHD?

Chen agreed with Neumann that clinicians should not take for granted that GI symptoms are necessarily a sign of GVHD. If he truly suspected that a patient had GVHD of the lower GI tract, he said he would admit the patient to the hospital and do a GI biopsy in order to exclude other diagnoses. If significant GI disease were found, he would put the patient on intravenous methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day.

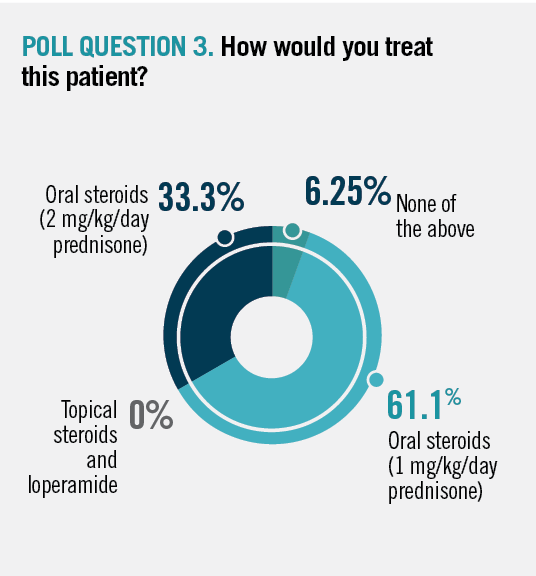

Most audience members said they would prescribe prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg (Poll question 3). Chao said the case illustrates the imprecision of GVHD diagnosis.

Poll Question 3. How would you treat this patient?

“We do biopsy the skin,” Chao said. “We biopsy the gut. But probably a dozen papers show that if we sent skin biopsies from autologous and allogenic [stem cell transplanted] patients [treated at] transplant centers, the pathologist cannot really tell the difference.”

Ultimately, Chao said, it’s up to clinicians to decide whether a patient has GVHD and to rule out other potential confounders.

Chronic GVHD in a Patient

For Hari, clinical judgment and experience are also key when deciding on treatment regimens.

“Treatment of chronic GVHD is an art, not a pure science,” he said.

In the case of a patient who has already tried prednisone but who is still experiencing significant symptoms of GVHD, Hari said he would tend to use extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), at least if the patient resided locally and would be available to come in for treatment twice a week for several weeks. Neumann said she would also suggest ECP, although she said there are times when she might treat with prednisone merely to get the patient back under control while other agents take effect.

“We would probably say ECP and ruxolitinib [Jakafi] would be the choices, but prednisone would be the choice if something seems very active, just to put the brakes on it and slow it down to let these other agents to kick in,” Neumann said.

Hari noted that 3 drugs are now approved for GVHD: ruxolitinib, belumosudil (Rezurock), and ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Ruxolitinib was the most recently approved in September 2021 from the FDA for chronic GVHD in patients whose first- or second-line therapy failed.7

In the REACH-3 trial (NCT03112603), 329 patients were randomly assigned on a 1:1 basis to either 10 mg of ruxolitinib twice per day or best available treatment, in which clinicians were allowed to choose from a list of 10 available therapies.

At 24 weeks, half of the patients (49.7%) in the ruxolitinib group experienced a complete or partial response to treatment, compared with 25.6% among the control group (odds ratio, 2.62; P = .001). Ruxolitinib also led to a median failure-free survival of greater than 18.6 months compared with just 5.7 months in the control group (HR, 0.37; P <.001). The most common adverse events were thrombocytopenia and anemia (15.2% and 12.7%, respectively) in the ruxolitinib group.8

Chen said that at his center, ruxolitinib is the standard therapy in second line. “We haven’t had a lot of success using ibrutinib in real-world experience,” he related. Despite having less experience with belumosudil, he said if a patient plateaued on second-line ruxolitinib, “we certainly have no hesitation about trying belumosudil in combination, with the caveat that those 2 agents have not been studied in combination as yet.”

Defining Steroid-Refractory GVHD

Hari said he tends to consider a case refractory when he sees progressive disease after at least 2 weeks on a steroid dose of at least 2 mg/kg in chronic GVHD, “or in patients who have not adequately responded after about 4 weeks of steroids, and then we are unable to taper steroids below 50% of the starting dose, maybe 0.5 mg/kg.”

Hari asked about other potential treatment options, including infliximab (Remicade), tocilizumab (Actemra), and mesenchymal stem cells. He said some of the agents have shown promise in phase 2 trials, but they are mostly unproven in a randomized trial setting. Chao agreed that the other agents appear to be effective in some patients, although he said it is not always clear why.

Tackling Challenges Ahead

Neumann reiterated that patient education regarding GVHD is critical for those who are undergoing transplants. Part of that education should include conversations about patient assistance programs, which, she said, are an important tool to help ensure that patients have access to high-cost novel therapeutics.

In terms of unmet need, Chao said the “holy grail” is finding ways to separate GVHD from graft-vs-leukemia (GVL) effects.

“Hopefully, at some point in time, we will be able to do that, which is to have a patient go to transplant with no GVHD but still preserve their GVL,” Chao said.

References

1. Flowers MED, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;117(11):3214-3219. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-08-302109

2. Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al; Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487-1496. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1203517

3. Soiffer RJ, Kim HT, McGuirk J, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, phase III clinical trial of anti–T-lymphocyte globulin to assess impact on chronic graft-versus-host disease–free survival in patients undergoing HLA-matched unrelated myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4003-4011. doi:10.1200/jco.2017.75.8177

4. Ram R, Gafter-Gvili A, Yeshurun M, Paul M, Raanani P, Shpilberg O. Prophylaxis regimens for GVHD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;43(8):643-653. doi:10.1038/bmt.2008.373

5. Malard F, Huang X-J, Sim JPY. Treatment and unmet needs in steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2020;34(5):1229-1240. doi:10.1038/s41375-020-0804-2

6. Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al. International, multicenter standardization of acute graft-versus-host disease clinical data collection: a report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):4-10. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.001

7. FDA approves ruxolitinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease. FDA. September 22, 2021. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://bit.ly/3ohR1LO

8. Zeiser R, Polverelli N, Ram R, et al; REACH3 Investigators. Ruxolitinib for glucocorticoid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(3):228-238. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2033122

EP: 1.Heterogeneity of GVHD

EP: 2.Allotransplantation and Prophylaxis Against GVHD

EP: 3.Educating Patients About Allotransplants and GVHD

EP: 4.Acute GVHD: Staging and Grading Criteria

EP: 5.Case 1: Treating a Patient With Acute GVHD

EP: 6.Treatment Options for Steroid-Refractory Acute GVHD

EP: 7.Clinical Burden of Chronic GVHD

EP: 8.Proactive Approaches to Preventing and Managing Chronic GVHD

EP: 9.Treatment Options for Steroid-Refractory Chronic GVHD

EP: 10.Case 2: Treatment Decisions for a Patient With Chronic GVHD

EP: 11.Selecting Therapy to Manage Steroid-Refractory Chronic GVHD

EP: 12.Recap: Experts Review Management of Chronic GVHD

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.