Recap: Recommendations for PARP Inhibitor Use in Prostate Cancer

A. Oliver Sartor, MD, discussen treatment options for PARP inhibitor use in patients with prostate cancer.

In a recent OncView™ discussion, A. Oliver Sartor, MD, a professor of medicine and the C.E. and Bernadine Laborde Professor of Cancer Research at Tulane University School of Medicine as well as the medical director of Tulane Cancer Center, in New Orleans, Louisiana, shared clinical experiences and perspectives regarding the use of PARP inhibitors to treat certain patients with prostate cancer.

To begin the discussion, Sartor talked about baseline testing strategies that he employs to match patients with the best systemic therapy. “In terms of molecular testing for metastatic disease, I always [want] to do germline testing. I may want to get additional genetics as well, [such as] somatic genetics within the tumor,” he said. “I also cover family history when I [begin] the analysis of a patient.”

Testing for both somatic and germline aberrations are important for the treatment of these patients, especially now that targeted therapies are becoming available in this space. “Findings like a BRCA mutation, [such as] BRCA2, which can often be picked up on primary prostate tissue, [are] important to be able to identify because of [their] treatment implications.”

Testing and Overcoming Barriers

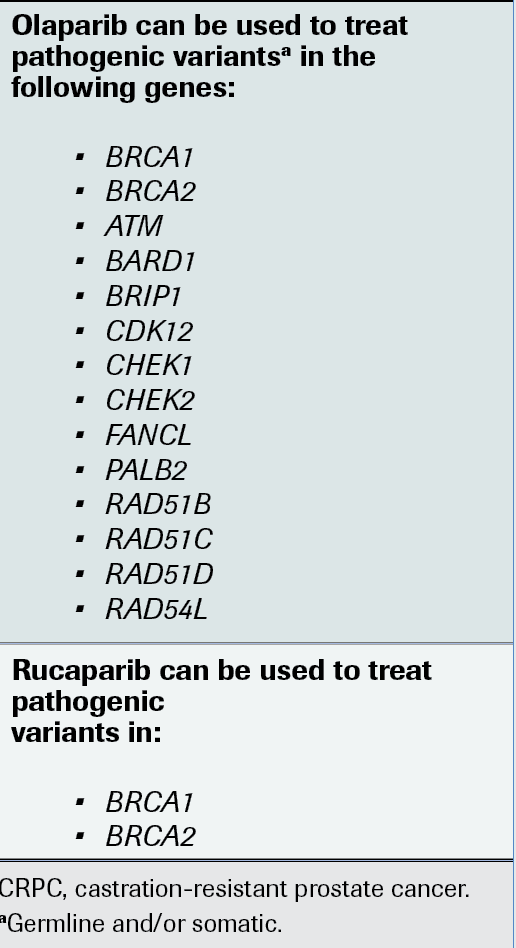

Sartor said testing for HRR genes such as BRCA1/2 and others like ATM, CHEK2, and PALB2 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) can assist clinicians in identifying patients who may be candidates for treatment with the PARP inhibitors olaparib (Lynparza) or rucaparib (Rubraca).

“In nongenomic manners, you can look at immunohistochemistry for things like MSH2 and MSH6—where, for the classic mismatch repair genes, you’ll get loss in protein staining. You can also pick it up genomically. It’s nice to do both,” Sartor said, adding that also testing for microsatellite instability and tumor mutational burden may be useful in determining which patients can receive pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in later lines of treatment.

Sartor noted, however, that various barriers may impede patient testing, such as reimbursement issues and inability to get adequate samples. “It’s not uncommon that we may have a patient who was seen and diagnosed in a community urology clinic 7 years ago, and then they show up to me with metastatic disease. If we’re trying to get archival tissue, then we must chase that community hospital sample from 7 years ago. That could be a substantial issue,” he said.

Selecting Treatment and Monitoring Metastatic CRPC

Sartor said selecting therapy for patients begins with a baseline assessment of a patient’s age and comorbidities. “The 49-year-old marathon runner [will be treated] differently from a 99-year-old patient. We must look at the basic parameters. Some people come in with a baseline thrombocytopenia, and some from chemotherapy may be particularly problematic,” he noted.

Physicians should also consider the possibility of treating their patients on a clinical trial. “There’s a big evolution going on,” Sartor said. “If you don’t have a particular clinical trial, then [being] cognizant of a center nearby that might be able to offer a good clinical trial is something to think about as well.”

Next, he advised looking at genomic alterations and prior treatments administered in the nonmetastatic setting to further help determine which agents are available to treat patients in later-line settings.

“You must look at a variety of parameters, including the cost of what you’re dealing with, affordability, the patient’s insurance, and their ability to pay. There are a lot of factors included in decision-making,” Sartor said.

For monitoring, Sartor said he emphasizes the need for communication between him and his patients often. “I explain it to patients this way: I need to know how you’re feeling,” he said.

Other important aspects for tracking disease progression include laboratory studies—such as complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver function, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels—plus imaging.

“By looking at these factors taken in total, we’re monitoring the disease of the patient and the toxicities of therapy. Then we’re putting it together in the context of good patient care and seeing the patient on a relatively frequent basis, particularly when we’re introducing new therapies,” Sartor said.

Role of PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer

Although many are familiar with PARP inhibitor therapy in the context of treating ovarian cancer, 2 of these agents have indications for treating those with metastatic CRPC, Sartor said.

In May 2020, the FDA granted full approval to olaparib for the treatment of adult patients with deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic HRR gene–mutated disease who have disease progression after either enzalutamide (Xtandi) or abiraterone (Zytiga).1

Regarding HHR gene mutations, Sartor says the data are not clear on which genes outside BRCA1 and BRCA2 indicate the greatest response, but the olaparib indication does allow for treatment of these patients.

“You have a series of other genes, including PALB2, that can be indications for the treatment,” Sartor said (FIGURE).2 “It doesn’t have to be somatic. It turns out that germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 can also apply.”

FIGURE. HRR Genes for Testing in CRPC

Data for this approval came from the PROfound study (NCT02987543),

a phase 3 trial of olaparib or physician’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone in men with metastatic CRPC who had disease progression while receiving a new hormonal agent. Patients were evaluated in 2 cohorts having either 1 alteration in BRCA1/2 or ATM (cohort A) or any of the other 12 prespecified HHR gene mutations (cohort B).

At the initial readout, olaparib demonstrated statistically significant boosts in radiographic progression-free survival vs the control group in cohort A (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.25-0.47; P < .001).3In an updated assessment, statistically significant improvements in cohorts A (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.50-0.97; P = .02) and numerical benefit in cohort B (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.63-1.49) were noted for overall survival (OS) with the PARP inhibitor. In the overall trial population, olaparib resulted in a median OS of 17.3 months vs 14.0 months with control therapy (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61-1.03), with 66% of the control group crossing over to receive olaparib at progression.4

“The overall survival data [were] quite strong despite the crossover,” Sartor said. “The bottom line is, the FDA saw fit to include all the homologous recombination repair genes within the FDA approval.”

Another agent, rucaparib, became available under accelerated approval in the same month for patients with germline and/or somatic deleterious BRCA mutation–associated disease who had previously received treatment with androgen receptor–directed therapy and taxane chemotherapy.5 Continuation of this indication will be contingent upon confirmation from a randomized trial.

Data supporting this decision came from the phase 2 TRITON2 trial (NCT02952534), in which rucaparib was examined in men with metastatic CRPC with alterations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 who progressed after 1 or 2 prior lines of next-generation antiandrogen therapy and 1 prior taxane-based chemotherapy. Objective response rate by independent radiologic review was 43.5% (95% CI, 31.0%-56.7%) and by investigator assessment was 50.8% (95% CI, 38.1%-63.4%), with responses being similar regardless of germline or somatic mutations. Confirmed PSA response was at 54.8% (95% CI, 45.2%-64.1%).6

With rucaparib, Sartor said there’s the potential to lower the treatment dose in patients who are responding well. “If you have a good response in a patient, then what you can do is create an even lower dosing and potentially have good activity. I have a patient right now on 300 mg once per day, and he’s having a great response. He had some significant anemia when he came into it, and he had a PALB2 [mutation] rather than a BRCA [mutation]. He just can’t tolerate the 300-mg twice-daily dosing; we had to dose-reduce him for anemia,” Sartor said.

Anemia is one of the more common adverse effects seen with this agent, along with fatigue and gastrointestinal effects, but “anemia is present in virtually all patients with metastatic CRPC, so not everybody is going to be affected to the same degree,” Sartor noted.

Sequencing of Therapies

Up front, Sartor said he looks to using hormones first to treat his patients. “I’m trying to get the novel hormones [into treatment] first because we have an accumulation of data that earlier use of these results in better survival advantages,” he said. “In fact, we have lots of new data that demonstrate in the castration-sensitive space [that] if you’re treating with these novel hormones, you do have an amazing effect on overall survival.”

After that, treatment options are few, with clinicians relying on genomics and precision medicine to select the next therapy.

To conclude, Sartor said physicians should be cognizant of multiple factors when treating their patients, including the use of up-front novel hormonal therapy, appropriate use of taxanes, the possibility of clinical trials, and utilization of biomarkers. “There are [many] things that you need to be open to—one [being] the idea of precision medicine,” he said.

References

1. FDA approves olaparib for HRR gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. FDA. Updated May 20, 2020. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://bit.ly/3bKgTKj

2. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate Cancer, version 1.2022. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://bit.ly/3ES5gNQ

3. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2091-2102. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911440

4. Hussain M, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Survival with olaparib in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2345-2357. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022485

5. FDA grants accelerated approval to rucaparib for

BRCA-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.FDA. Updated May 15, 2020. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://bit.ly/3bN56eu

6. Abida W, Patnaik A, Campbell D, et al; TRITON2 investigators. Rucaparib in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(32):3763-3772. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.01035

EP: 1.Diagnosing Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 2.Biomarker Testing in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 3.Treatment Options for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 4.The Role of PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer

EP: 5.Rucaparib for Prostate Cancer

EP: 6.Advances in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

EP: 7.Routinely Ordered Testing for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 8.Biomarker Testing Protocols for Metastatic Prostate Cancer and What to Look For

EP: 9.BRCA1/2 in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 10.Systemic Treatment Options for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

EP: 11.Selecting Appropriate Treatment and Monitoring Patients on Metastatic Prostate Cancer Therapy

EP: 12.The Role of PARP Inhibitors and Adverse Events in Metastatic Prostate Cancer Therapy

EP: 13.Other Factors Considered When Adding PARP Inhibitors to Metastatic Prostate Cancer Therapy

EP: 14.Patient Access and Metastatic Prostate Cancer Therapy

EP: 15.Sequencing Strategies for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Therapy

EP: 16.Exciting Advances in the Therapeutic Space and Clinical Pearls for Treating Metastatic Prostate Cancer

EP: 17.Recap: Recommendations for PARP Inhibitor Use in Prostate Cancer

EP: 18.Recap: Testing and Treating Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

Prolaris in Practice: Guiding ADT Benefits, Clinical Application, and Expert Insights From ACRO 2025

April 15th 2025Steven E. Finkelstein, MD, DABR, FACRO discuses how Prolaris distinguishes itself from other genomic biomarker platforms by providing uniquely actionable clinical information that quantifies the absolute benefit of androgen deprivation therapy when added to radiation therapy, offering clinicians a more precise tool for personalizing prostate cancer treatment strategies.